All collectors can appreciate the notion of opening a book they have acquired and being pleasantly surprised to find a signature or inscription of the author. That’s not quite what happened to us recently, but what did happen is just as noteworthy.

Recently we acquired a copy of the 1944 wartime reprint of Churchill’s biography of his early life. By itself, the book is a desirable, but unremarkable edition. But this particular copy is anything but unremarkable. When we bought it, we knew it was inscribed. And we knew it was inscribed to the man who helped create and served as custodian of Churchill’s Cabinet War Rooms. What we did not find out until we opened the book is that it was presented as a wartime “souvenir” (Churchill’s word for it, not ours!) on the final day of Churchill’s wartime premiership.

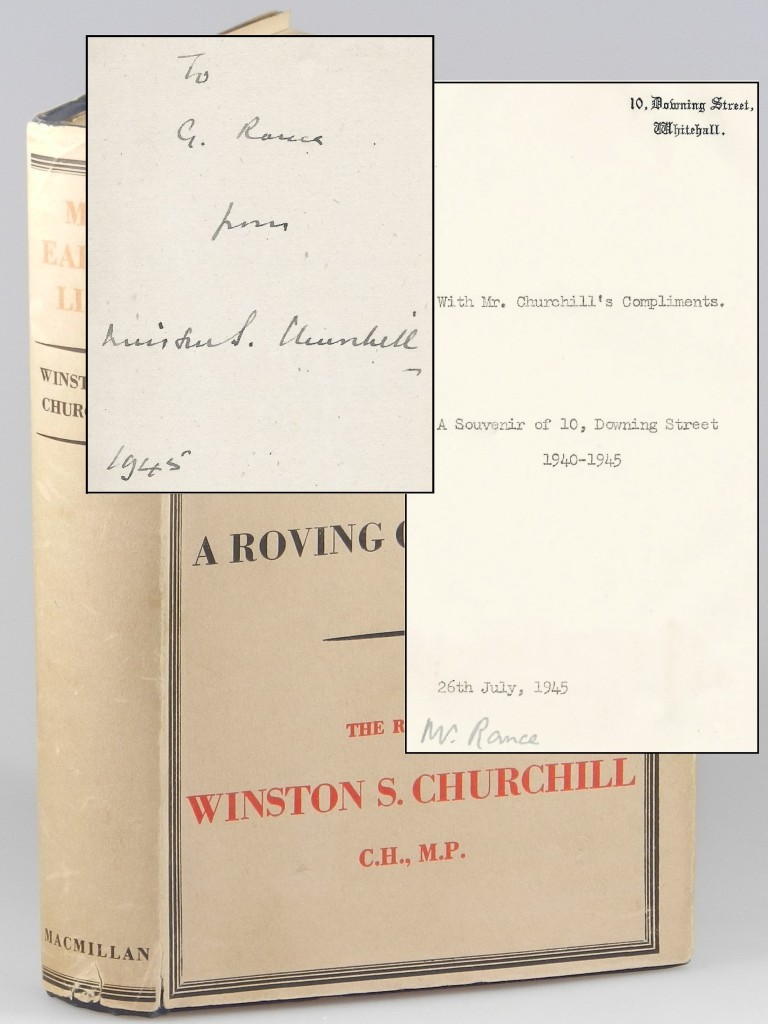

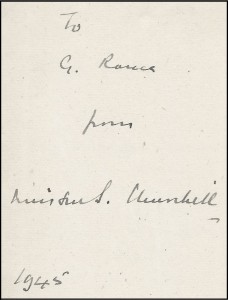

The inscription, in black ink in five lines on the front free endpaper, reads: “To | G. Rance | from | Winston S. Churchill | 1945”.

Affixed to the verso of the following blank end sheet is a typed presentation message on “10 Downing Street, Whitehall” stationery. Four typed lines read: “With Mr. Churchill’s Compliments. | A Souvenir of 10, Downing Street | 1940-1945 | 26th July, 1945”. Below the date, the words “Mr. Rance” are inked in black. July 26th would of course be the last day Churchill would have ministerial 10 Downing Street privileges until his second and final premiership began in October 1951.

The Cabinet War Rooms

The sprawling maze of subterranean offices below Whitehall that became the Cabinet War Rooms were meant to provide a secret location safe from air raids for the War Cabinet to meet. The Cabinet War Rooms became fully operational on 27 August 1939, “But it was under Churchill [who became prime minister in May 1940] that it assumed the air of urgency and excitement which a visitor can still feel today.”

The sprawling maze of subterranean offices below Whitehall that became the Cabinet War Rooms were meant to provide a secret location safe from air raids for the War Cabinet to meet. The Cabinet War Rooms became fully operational on 27 August 1939, “But it was under Churchill [who became prime minister in May 1940] that it assumed the air of urgency and excitement which a visitor can still feel today.”

Soon after becoming Prime Minister, “Churchill made an inspection of his fortress. He arrived without warning, swept through the rooms, then asked for the exit that let most directly to No. 10 Downing Street.” The Cabinet War Rooms came to serve as the center of Britain’s war effort. Churchill’s War Cabinet met here 115 times.

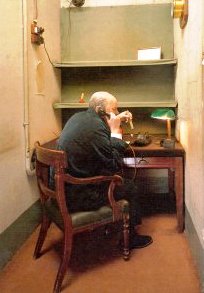

From here Churchill delivered four of his wartime addresses and “from a room no larger than a lavatory held… conversations with President Roosevelt” using a phone installed for the purpose by the U.S. Signal Corps. “The Cabinet War Rooms were in use 24 hours a day until 16 August 1945, when the lights were turned off in the Map Room for the first time in six years.”

From here Churchill delivered four of his wartime addresses and “from a room no larger than a lavatory held… conversations with President Roosevelt” using a phone installed for the purpose by the U.S. Signal Corps. “The Cabinet War Rooms were in use 24 hours a day until 16 August 1945, when the lights were turned off in the Map Room for the first time in six years.”

To the 300 people who worked here during the Second World War, it was “The Hole” or simply “down there” but to Churchill it was “This Secret Place.” More than any other individual, the man who helped create and keep it secret was George Rance.

George Rance

An ex-Army Rifle Brigade sergeant the same age as Churchill, Rance was a member of the Civil Service tasked with filling pay sheets of government ministry charwomen when he was called upon to help set up the Cabinet War Rooms. In this role “Rance proved to be a man of vast talent and enterprise.” It was Rance who fitted out the bunker with furniture, equipment, and supplies, attaching unauthorized applications to legitimate ministry orders and having the surplus material delivered to ‘c/o Mr. Rance’ and then smuggled into the War Rooms. “With Rance holding the only keys and the ‘c/o Mr. Rance’ address effectively becoming the codeword for the entire operation, secrecy was maintained.”

Secrecy was no joke. Despite a reinforced concrete slab up to three metres thick installed above the rooms in December 1940, a hit from anything larger than a 500-pound (227-kg) bomb could have penetrated the building and destroyed the War Rooms.” Hence “Secrecy was the best security for the site.” But this was Churchill’s bunker, and so an intensity and seriousness could never fully suppress impish impulse. Rance made a board with movable strips to indicate the ever-changing English weather outside. The board would be changed to “Windy” when bombing was reported.

Secrecy was no joke. Despite a reinforced concrete slab up to three metres thick installed above the rooms in December 1940, a hit from anything larger than a 500-pound (227-kg) bomb could have penetrated the building and destroyed the War Rooms.” Hence “Secrecy was the best security for the site.” But this was Churchill’s bunker, and so an intensity and seriousness could never fully suppress impish impulse. Rance made a board with movable strips to indicate the ever-changing English weather outside. The board would be changed to “Windy” when bombing was reported.

“On one occasion, when Churchill was due to return from a journey, Rance was asked by Mrs. Churchill to think up a small surprise. Someone had sent the Old Boss a small black wooden cat as a mascot. Rance made a small wooden wall for the cat to peer over. Churchill was delighted with the gift and put it on his bedside table. On the way back to his office Rance met an august admiral who asked, “How is the Prime Minister?” “Very well, sir,” Rance replied. “When I left him he was playing with his toy cat.”

Churchill had his First World War service revolver and a dagger on his Cabinet War Rooms desk. When George VI paid a visit during the darkest days of the war, he noticed the dagger and asked its purpose. “For Mr. Churchill, sir,” Rance replied. “So that he can use it when Hitler is brought before him.”

Rance ran the bunker throughout the war, eventually receiving an MBE. “If it was the personality of Churchill that gave This Secret Place its character, it was the skill of George Rance that kept things running smoothly… Both were old soldiers. Both were the same age… Of course one was the Prime Minister and the other the custodian, but it was more a feeling of the colonel of the Regiment and the Regimental Sergeant-Major.” To Churchill’s requests, Rance would most often respond with “Saah” stamp his foot. But if Churchill “wanted Rance to do something that Rance felt was out of order, Rance did not hesitate to say so.” Churchill spent so much time in the Cabinet War Rooms that he literally argued with Rance over placement of his bed (an argument which Rance won).

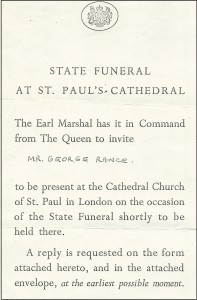

In 1950 when Rance retired, Churchill wrote to him: “This secret place began under the address ‘c/o Mr. Rance’ and under your faithful custody it remained until it grew into the great wartime centre.” In 1965, at the age of 91, Rance sat in a back pew of St. Paul’s Cathedral during Churchill’s state funeral. “He remembered then the few gruff words that had passed between the ex Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the ex-Sergeant of the Rifle Brigade when the war was over. ‘I suppose, Rance,’ Churchill had said ‘you think I don’t know all you have done. Well, I do. Thank you. Thank you very much.”

In 1950 when Rance retired, Churchill wrote to him: “This secret place began under the address ‘c/o Mr. Rance’ and under your faithful custody it remained until it grew into the great wartime centre.” In 1965, at the age of 91, Rance sat in a back pew of St. Paul’s Cathedral during Churchill’s state funeral. “He remembered then the few gruff words that had passed between the ex Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the ex-Sergeant of the Rifle Brigade when the war was over. ‘I suppose, Rance,’ Churchill had said ‘you think I don’t know all you have done. Well, I do. Thank you. Thank you very much.”

Clearly, Churchill did remember Rance with gratitude. On July 26, 1945, having done so much to win the war, Churchill faced frustration of his postwar plans when his Conservatives lost the British General Election. That day, Churchill resigned, yielding the premiership to Clement Atlee. It is on this very day – the last of his wartime premiership and the last day that 10 Downing Street stationery would bear messages from Churchill until October 1951 – that this inscribed copy was presented to George Rance.

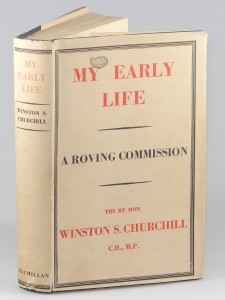

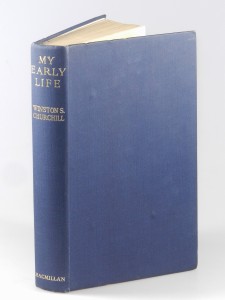

Edition and condition

This is the fourth and final 1944 wartime reprint of Churchill’s extremely popular autobiography, covering the years from his birth in 1874 to his first few years in Parliament. Macmillan acquired the rights after the original publisher, Thornton Butterworth, went under in 1940. During the war, Macmillan issued these desirable reprints (issued from first edition plates) in dark blue cloth wrapped in attractive tan dust jackets.

This is the fourth and final 1944 wartime reprint of Churchill’s extremely popular autobiography, covering the years from his birth in 1874 to his first few years in Parliament. Macmillan acquired the rights after the original publisher, Thornton Butterworth, went under in 1940. During the war, Macmillan issued these desirable reprints (issued from first edition plates) in dark blue cloth wrapped in attractive tan dust jackets.

Two more surprises awaited us when we examined this book. First was finding this inscribed presentation copy remained in near fine condition, clean and tight with unusually well-preserved binding and contents. The second was finding what appears to be an old copy of Rance’s invitation to Churchill’s state funeral laid in between the pages.

Two more surprises awaited us when we examined this book. First was finding this inscribed presentation copy remained in near fine condition, clean and tight with unusually well-preserved binding and contents. The second was finding what appears to be an old copy of Rance’s invitation to Churchill’s state funeral laid in between the pages.

See this book offered for sale on our website HERE.