Among the trove of Kipling’s works we have recently catalogued and offered to our customers, you will not find this copy of Plain Tales from the Hills.

Among the trove of Kipling’s works we have recently catalogued and offered to our customers, you will not find this copy of Plain Tales from the Hills.

It is the prerogative of the bookseller to collect, and this copy has been appropriated to the collection of this bookseller.

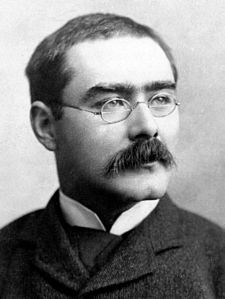

Nearly everyone knows something of Kipling, even if they don’t know it as Kipling’s. Many have a favorite Kipling story or verse. I understand choosing one of Kipling’s Jungle Books or Kim, the poems “If” or “Recessional”, or even the Just So Stories. But for me, Kipling’s vital spark, the deliciously imperfect, often oblique light and shadow glint behind Kipling’s trademark round spectacles, resides in his Plain Tales from the Hills.

Nearly everyone knows something of Kipling, even if they don’t know it as Kipling’s. Many have a favorite Kipling story or verse. I understand choosing one of Kipling’s Jungle Books or Kim, the poems “If” or “Recessional”, or even the Just So Stories. But for me, Kipling’s vital spark, the deliciously imperfect, often oblique light and shadow glint behind Kipling’s trademark round spectacles, resides in his Plain Tales from the Hills.

Plain Tales from the Hills was Kipling’s first prose collection, originally published in Calcutta when he had just turned twenty-two. The superficial summary is that the stories paint a picture of various different aspects of life in British India. To me, Plain Tales is Kipling finding his voice as an English Euripides, a voice at once both quintessentially of his culture and yet essentially, observationally, compellingly apart. This is the Kipling some would ignorantly veil as an icon of tradition, subtly weaving subversive patterns in the traditional fabric.

Plain Tales from the Hills was Kipling’s first prose collection, originally published in Calcutta when he had just turned twenty-two. The superficial summary is that the stories paint a picture of various different aspects of life in British India. To me, Plain Tales is Kipling finding his voice as an English Euripides, a voice at once both quintessentially of his culture and yet essentially, observationally, compellingly apart. This is the Kipling some would ignorantly veil as an icon of tradition, subtly weaving subversive patterns in the traditional fabric.

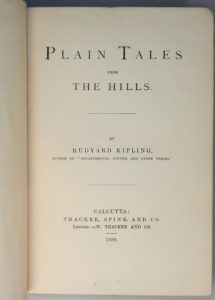

From 1882 to 1887 Kipling worked as a journalist in India for the Civil and Military Gazette. There, between 11 November 1886 and 10 June 1887, thirty-nine short stories appeared unattributed under the serial title “Plain Tales from the Hills“. Twenty-nine of those stories, along with eleven new ones, were published in January 1888 by Kipling’s Indian publisher, forming his second book-length work, following Departmental Ditties and Other Verses in 1886.

From 1882 to 1887 Kipling worked as a journalist in India for the Civil and Military Gazette. There, between 11 November 1886 and 10 June 1887, thirty-nine short stories appeared unattributed under the serial title “Plain Tales from the Hills“. Twenty-nine of those stories, along with eleven new ones, were published in January 1888 by Kipling’s Indian publisher, forming his second book-length work, following Departmental Ditties and Other Verses in 1886.

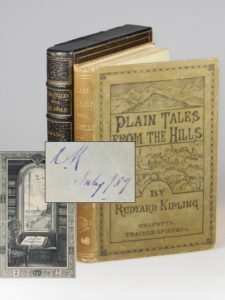

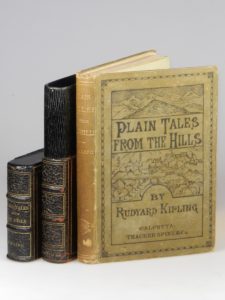

This particular first edition copy wears its colonial Indian roots with pride. It is the second issue, with the front cover illustration by Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, of a gated city on the plains below hills. The covers are mottled, with some insect bore holes, several of which penetrate the text within. But the binding and endpapers are original. On those endpapers (the front free endpaper) are Kipling’s initials and the date “July/89” and facing, affixed to the front pastedown, is the decorative bookplate of Nelson Doubleday.

This particular first edition copy wears its colonial Indian roots with pride. It is the second issue, with the front cover illustration by Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, of a gated city on the plains below hills. The covers are mottled, with some insect bore holes, several of which penetrate the text within. But the binding and endpapers are original. On those endpapers (the front free endpaper) are Kipling’s initials and the date “July/89” and facing, affixed to the front pastedown, is the decorative bookplate of Nelson Doubleday.

1889 is the year Kipling left India for America, leaving behind “the sights and the sounds and the smells | That ran with our youth in the eye of the sun.” (“Song of the Wise Children” 1902)

Nelson Doubleday was the son of Frank Nelson Doubleday, Kipling’s friend and founder of the Doubleday publishing empire. F.N. Doubleday began work in the publishing industry working for Charles Scribner’s Sons. His 18-year career with Scribner’s included the task of assembling a complete set of Kipling’s works for publication in a collected edition in 1897. His work with Kipling on this endeavor sparked a friendship and partnership that lasted for decades. Kipling affectionately gave Doubleday the honorific nickname “Effendi”, a play on the initials of his name – F.N.D. It was Frank’s son, Nelson who, at age seven, wrote Kipling a precocious letter exhorting him to write more “Just So” stories and suggesting topics for same, thus catalyzing what would become one of Kipling’s most famous and enduring works. Nelson was president of the firm from 1922 to 1946, as was Nelson Jr., from 1978 to 1983.

Nelson Doubleday was the son of Frank Nelson Doubleday, Kipling’s friend and founder of the Doubleday publishing empire. F.N. Doubleday began work in the publishing industry working for Charles Scribner’s Sons. His 18-year career with Scribner’s included the task of assembling a complete set of Kipling’s works for publication in a collected edition in 1897. His work with Kipling on this endeavor sparked a friendship and partnership that lasted for decades. Kipling affectionately gave Doubleday the honorific nickname “Effendi”, a play on the initials of his name – F.N.D. It was Frank’s son, Nelson who, at age seven, wrote Kipling a precocious letter exhorting him to write more “Just So” stories and suggesting topics for same, thus catalyzing what would become one of Kipling’s most famous and enduring works. Nelson was president of the firm from 1922 to 1946, as was Nelson Jr., from 1978 to 1983.

This copy came to us from the Doubleday family library in a worn but lovely two-piece full leather case bearing the swastika on the front cover. Like perhaps India itself, the swastika serves to remind us that the world – and the words and symbols we use to engage and describe it – are far older than the transgressions and horrors of recent history. The word swastika comes from the

This copy came to us from the Doubleday family library in a worn but lovely two-piece full leather case bearing the swastika on the front cover. Like perhaps India itself, the swastika serves to remind us that the world – and the words and symbols we use to engage and describe it – are far older than the transgressions and horrors of recent history. The word swastika comes from the  Sanskrit svastika, which means “good fortune”, and this ancient hooked cross symbol was used at least 5,000 years before being polluted by association with Hitler’s Reich. It remains a sacred symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Odinism. The swastika is a symbol common to many editions of Kipling’s works and came to Kipling’s attention through his father’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Indian art.

Sanskrit svastika, which means “good fortune”, and this ancient hooked cross symbol was used at least 5,000 years before being polluted by association with Hitler’s Reich. It remains a sacred symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Odinism. The swastika is a symbol common to many editions of Kipling’s works and came to Kipling’s attention through his father’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Indian art.

Born in India, Kipling cut his literary teeth there as a newspaper editor and writer, and India’s vividness and vitality clearly proved indelible, both for Kipling and his readers. Kipling was in his twenties when his stories of Anglo-Indian life made him a literary celebrity, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907 “in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author”. He was the first English language author awarded and remains the youngest person to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Born in India, Kipling cut his literary teeth there as a newspaper editor and writer, and India’s vividness and vitality clearly proved indelible, both for Kipling and his readers. Kipling was in his twenties when his stories of Anglo-Indian life made him a literary celebrity, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907 “in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author”. He was the first English language author awarded and remains the youngest person to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Beyond the transmogrifications of Disney films, Kipling is chiefly remembered for his celebration of British imperialism, tales and poems of British soldiers in India, and his tales for children. Despite this reputation, Kipling’s extraordinary body of work “eludes all labels in its range and variety… Kipling’s work is not only of the highest artistic excellence, it is deeply humane and fully expresses the sense of one of his favourite texts: ‘Praised be Allah for the diversity of his creatures.’”

Though rooted in an Empire sensibility that became archaic even before his death, Kipling’s best tales remain iconic, even elemental examples of the storyteller’s craft. “There has yet been no writer of short stories in English to challenge his achievement, which ranges through space from India to the home counties, and through time from Stone Age man to the contemporary world of football matches and motor cars. These stories, moreover, exhibit every kind of treatment, from the farcical to the tragic, and their structures vary from the simplest anecdote to the most complex and allusive philosophical fiction, dense enough to support endless exegesis and commentary.” (ODNB)

That is a lovely erudition.

To me, the plainer tale is that Kipling’s characters – often only half-drawn and furtively glimpsed – are “Other” to themselves more than to place or to one another. Like Frost’s wood, Kipling’s India is “lovely, dark and deep”– a tangled banyan of humanity whose roots continue to propagate and accrete. In the interstices of British Raj and native soil. In the dense, humid, redolent air between reader and writer.

I encourage you to read Plain Tales from the Hills. You just can’t borrow my copy.