On 14 September 1943, sixty-eight-year-old Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill was returning from a lengthy trip to North America during which he conferred extensively with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Among many issues clamoring for his attention were the newly-begun invasion of the Italian Peninsula, accommodation of both his American allies and the paranoid petulance of Stalin, conception and timing of Allied invasion of northern Europe, a forthcoming Allied foreign ministers conference in Moscow, and how to constructively shape the post-war world and Britain’s place in it, even as some of the most bloody fighting of the war lay still ahead and far from resolved in outcome. Despite these pressing cares and an intervening 45 years of life experience, in the Admiral’s Cabin of the battleship Renown on his way back to England and to war, “Churchill called for a box of matches, and demonstrated to those present the disposition of Kitchener’s forces at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.”[i]

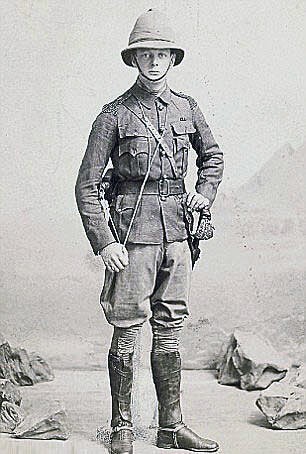

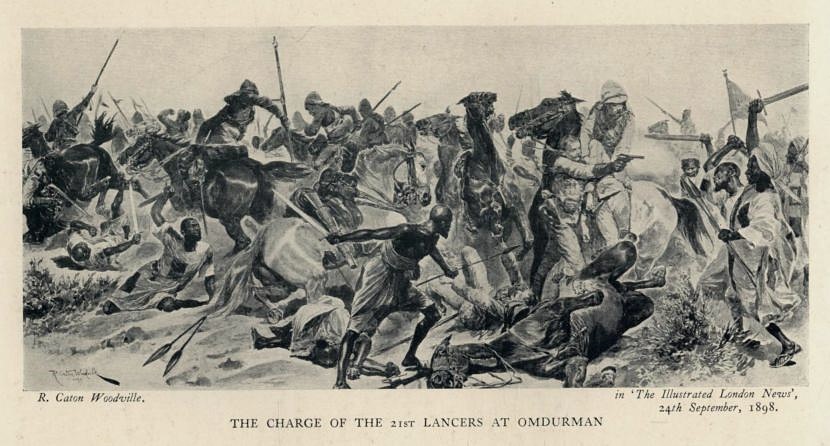

Long before he learned to fly, helped conceive the first tanks, converted the British Navy to oil-burning ships, directed development of the earliest computers, and presided as Prime Minister over the first British nuclear weapons test, in the twilight of Queen Victoria’s reign Churchill rode a horse into battle against the Dervishes of central Sudan in “the last great British cavalry charge”.

It was on horseback at Omdurman that Churchill viscerally comprehended “the shoddiness of war. You cannot gilt it. The raw comes through.”[ii] It was the death of a friend and fellow officer that shaped and charged this lesson. And it was in a letter of September 1898, posted by Churchill to a fellow officer as he was returning home, that Churchill gave a fittingly raw, affecting, personal remembrance of this fallen comrade.

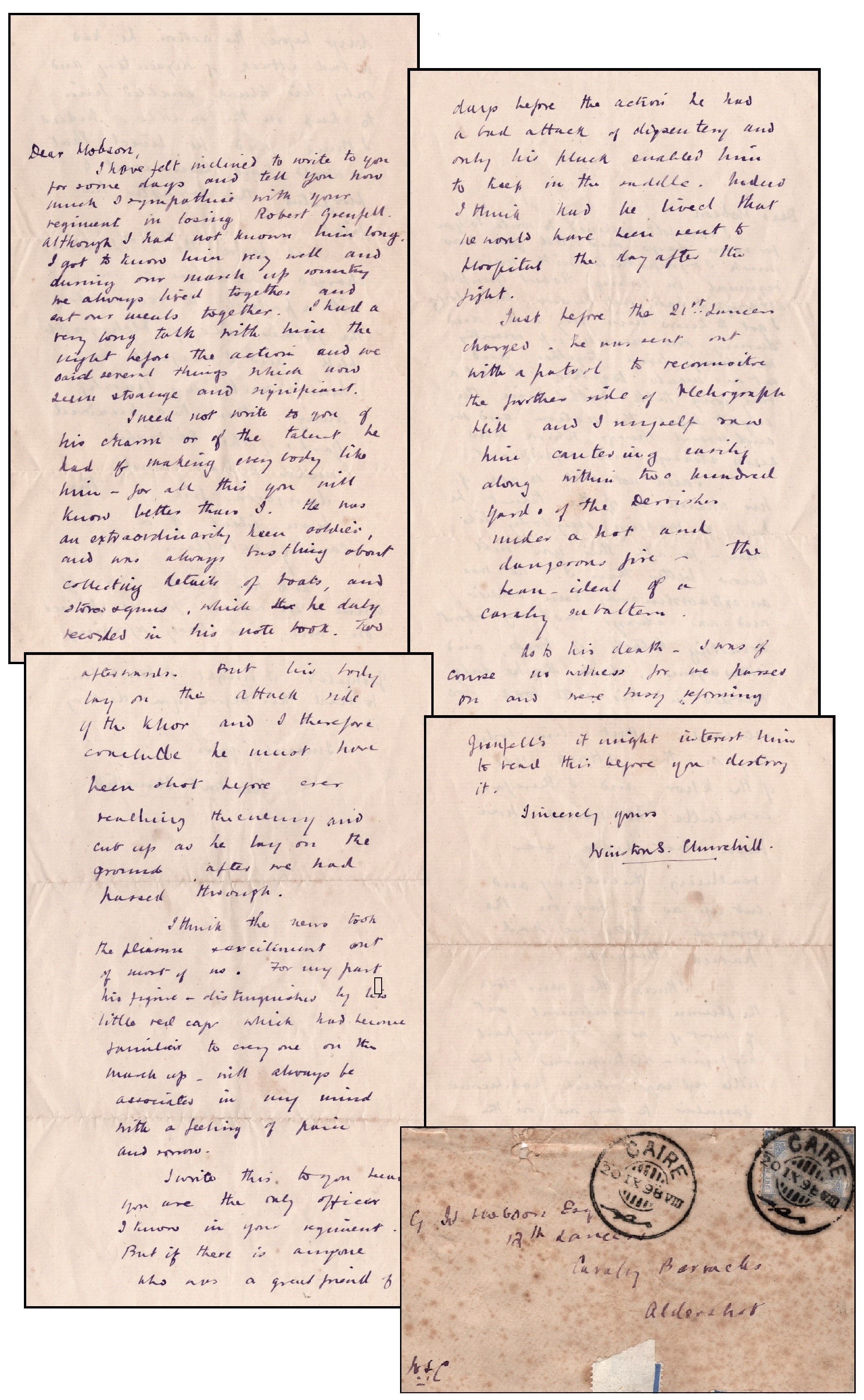

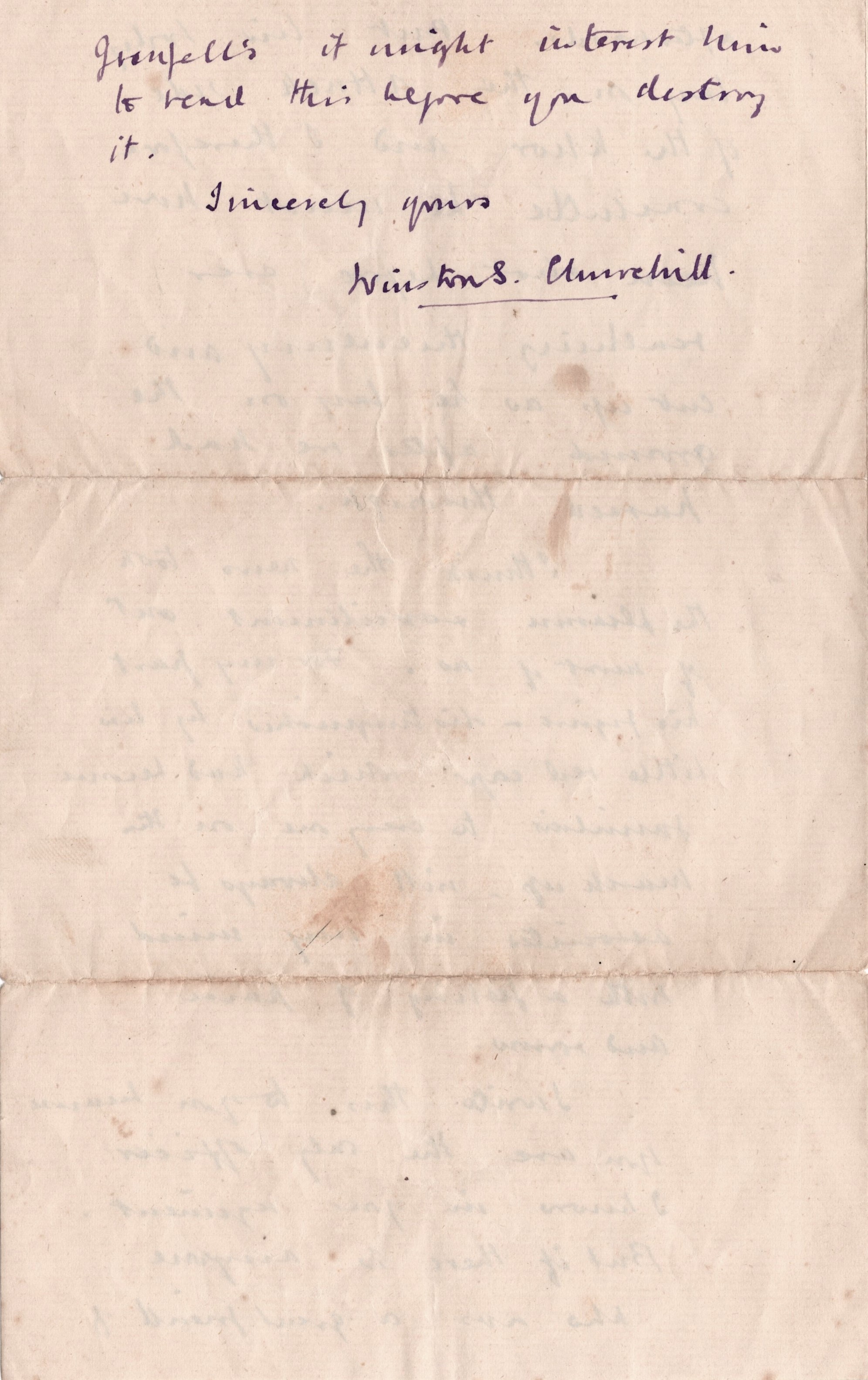

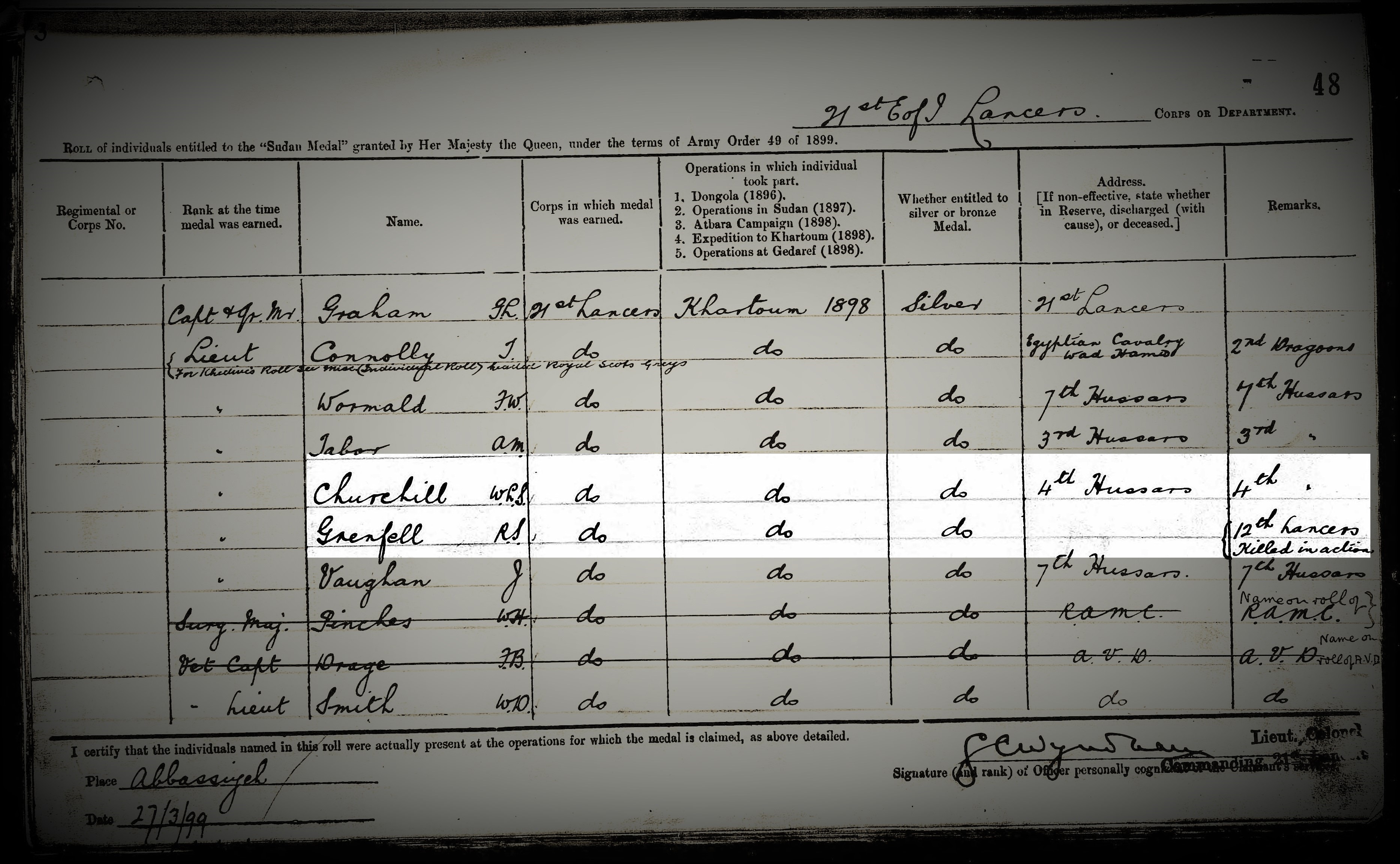

This autograph letter with its original envelope postmarked 20 September 1898 from Cairo was written by Winston Churchill to G.W. Hobson regarding the death of their mutual friend Robert Grenfell in the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898.

Churchill produced no shortage of letters in his long and prolifically worded life. Many survive, but seldom do we encounter a letter of such early candor and consequence. In both respects this letter is superlative.

It is enough that the letter is a wrenching tribute to a fallen friend and fellow officer from the 23-year-old Churchill, fresh from the battlefield. And it is noteworthy that the letter not only survives, but remains accompanied by the original envelope posted from Egypt as Churchill was en route home to England. Several additional factors render this letter not merely precious and compelling, but significant.

First, this letter is neither referenced nor recorded in either the narrative or documents volumes of Churchill’s official biography. Second, although Churchill wrote about Grenfell many times in both print and correspondence, this letter appears to record the fullest and most deeply personal account of both Grenfell and Churchill’s friendship with him. Finally, it appears that the grisly death of his friend and fellow young officer was formative to Churchill’s conceptions of the hazards and necessities of battle, the role of chance in war, and a sense of his personal luck. These conceptions carried Churchill through countless additional battles, both as a soldier and a leader, for more than half a century after Omdurman.

The letter is inked entirely in Churchill’s hand on a single sheet of laid paper measuring 10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.3 cm) folded once vertically to form the four panels on which the letter is written, and subsequently folded twice horizontally to fit into the accompanying envelope. Condition of the letter approaches very good. The purple ink remains vivid, distinct with no appreciable fading. The paper is lightly spotted and toned with tiny loss to some fold corners and two small separations along fold lines, but with no loss to the contents.

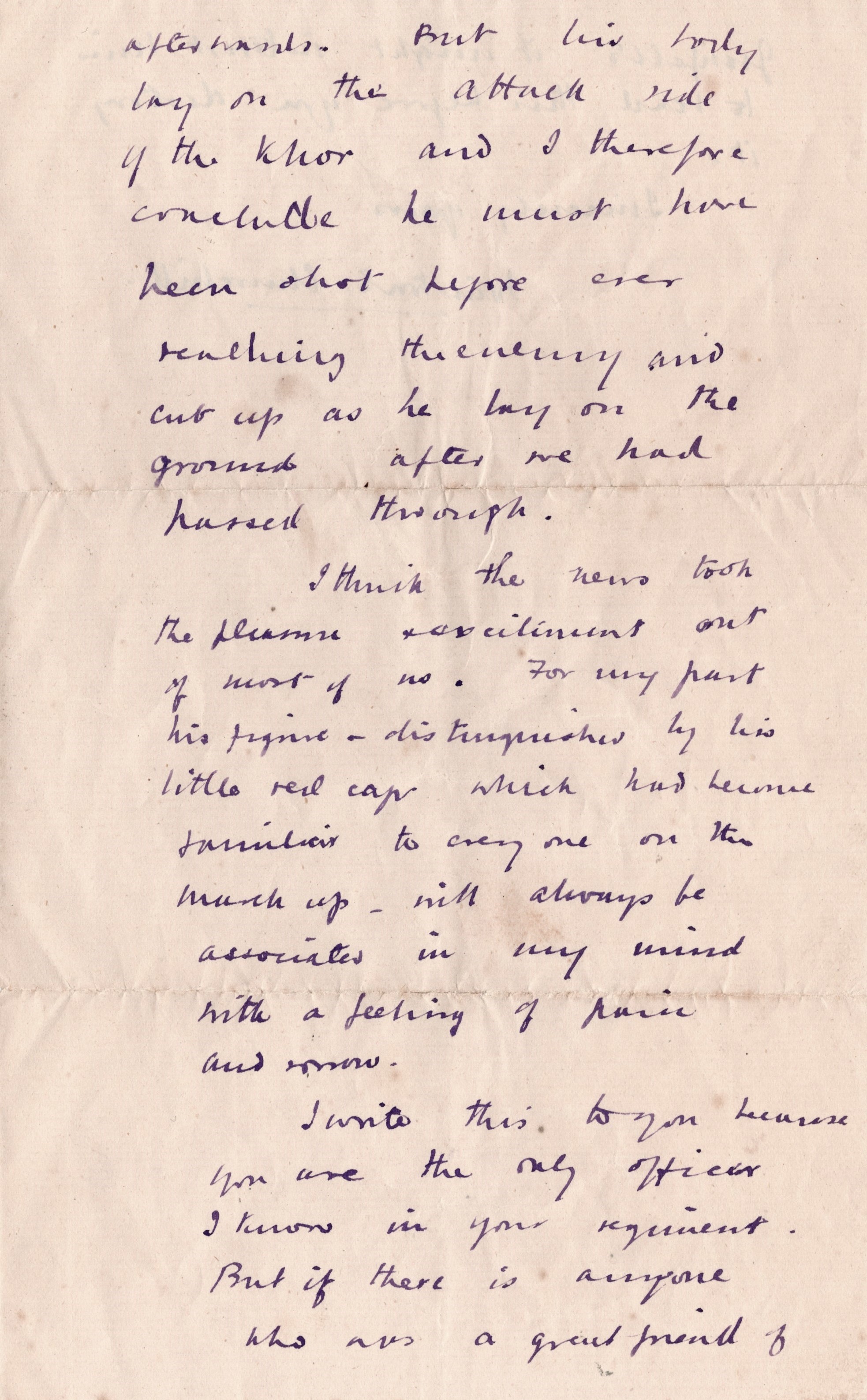

In 377 words in six paragraphs inked in 75 lines on all four panels, the letter reads:

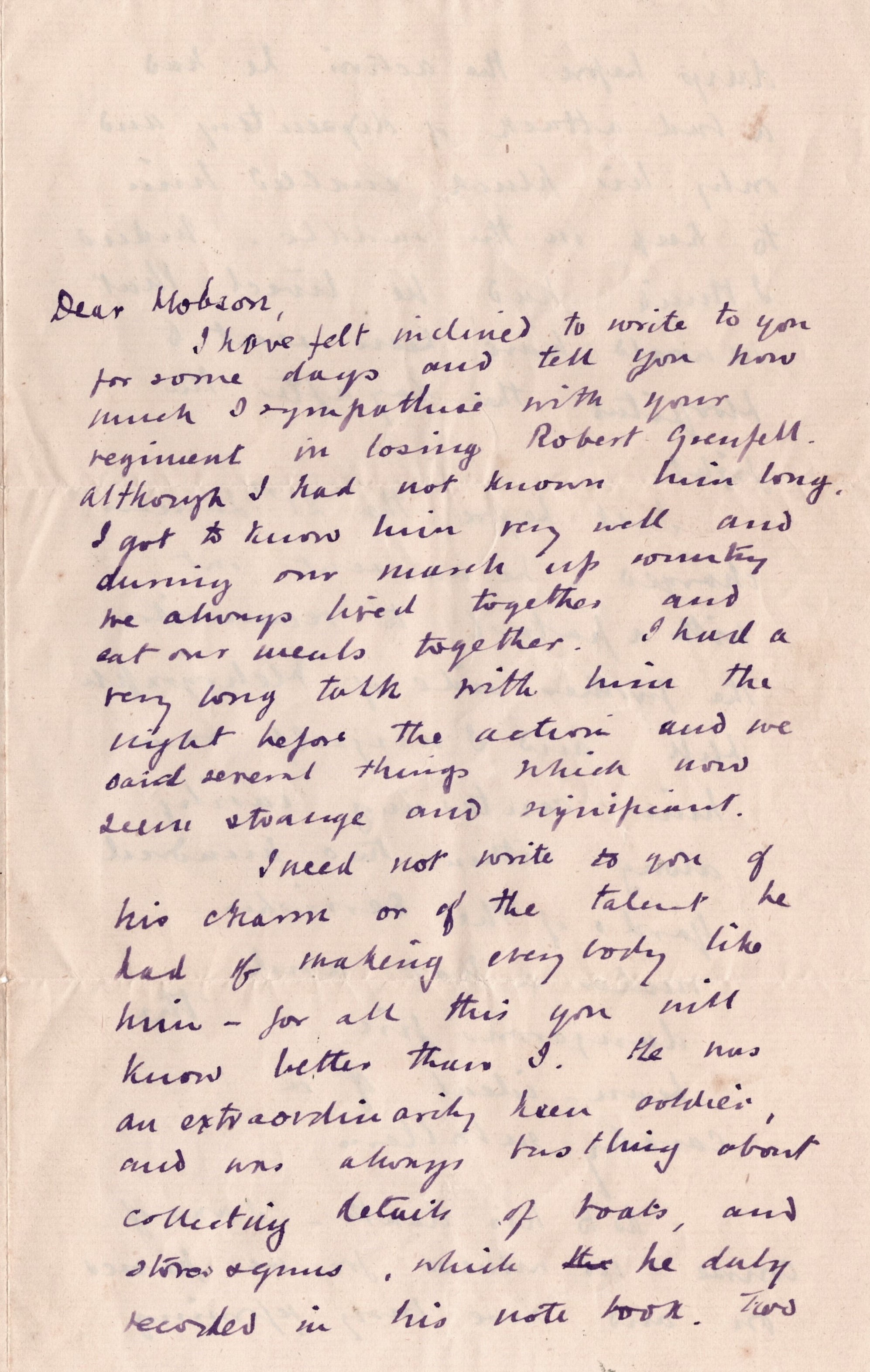

“Dear Hobson,

I have felt inclined to write to you for some days and tell you how much I sympathise with your regiment in losing Robert Grenfell. Although I had not known him long, I got to know him very well and during our march up country we always lived together and ate our meals together. I had a very long talk with him the night before the action and we said several things which now seem strange and significant.

I need not write to you of his charm or of the talent he had of making everybody like him – for all this you will know better than I. He was an extraordinarily keen soldier, and was always bustling about collecting details of boats, and stores and guns, which he duly recorded in his note book. Two days before the action he had a bad attack of dysentery and only his pluck enabled him to keep in the saddle. Indeed I think had he lived that he would have been sent to hospital the day after the fight.

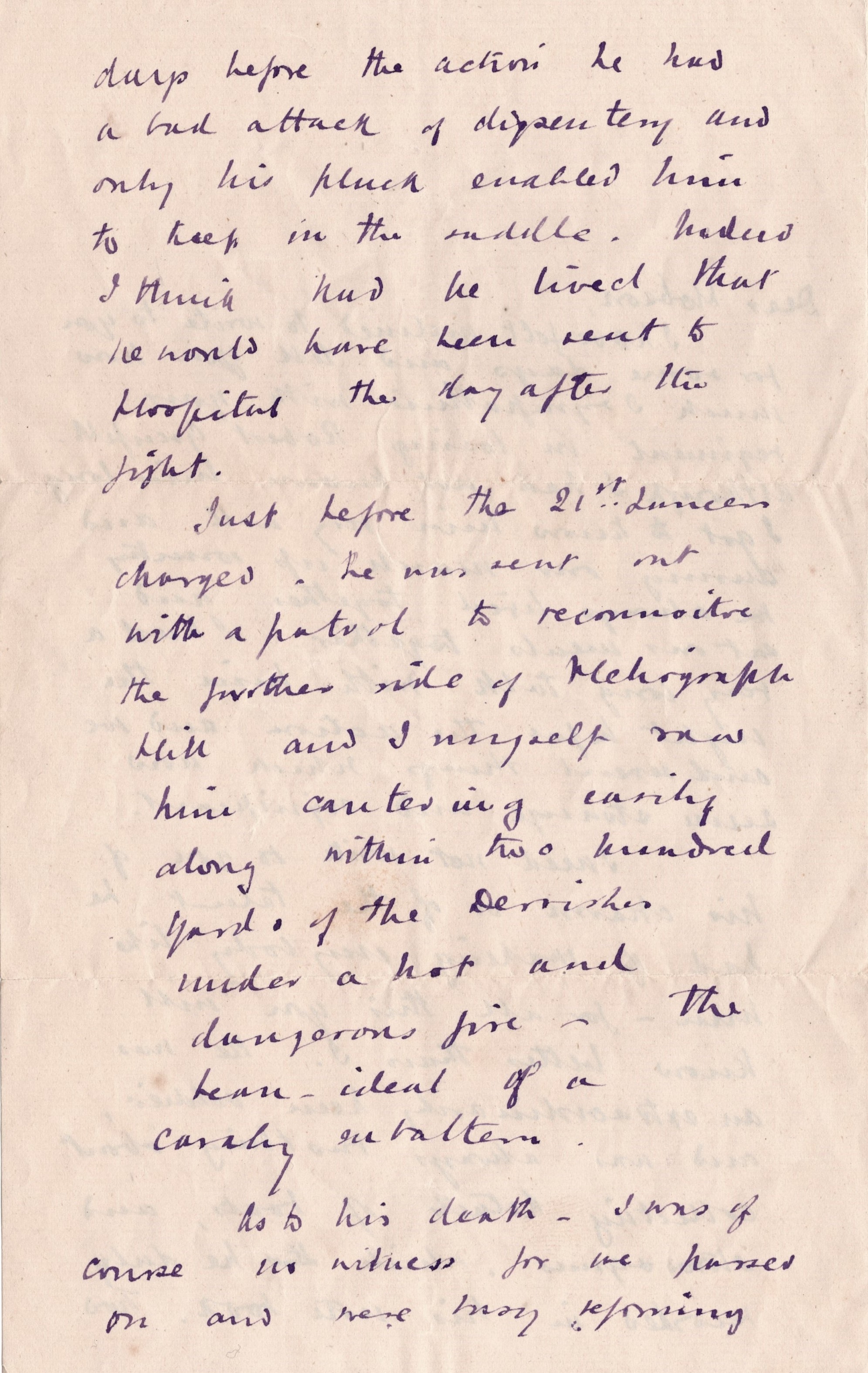

Just before the 21st Lancers charged, he was sent out with a patrol to reconnoitre the further side of Heliograph Hill and I myself saw him cantering easily along within two hundred yards of the Dervishes under a hot and dangerous fire – the beau-ideal of a cavalry subaltern.

As to his death – I was of course no witness for we passed on and were busy reforming afterwards. But his body lay on the attack side of the Khor and I therefore conclude he must have been shot before ever reaching the enemy and cut up as he lay on the ground after we had passed through.

I think the news took the pleasure and excitement out of most of us. For my part his figure – distinguished by his little red cap which had become familiar to everyone on the march up – will always be associated in my mind with a feeling of pain and sorrow.

I write this to you because you are the only officer I know in your regiment. But if there is anyone who was a great friend of Grenfell’s it might interest him to read this before you destroy it.

Sincerely yours

Winston S. Churchill”

The letter is accompanied by the original envelope addressed in Churchill’s hand to “G. W. Hobson, Esq | 12thLancers | Cavalry Barracks | Aldershot” and the envelope itself is also initialed “W.S.C”. by Churchill at the lower left.

The upper right of the envelope features two circular postmark ink stamps, both reading “CAIRE 20 IX 98 VIII”, the second stamped over a rectangular stamp plus one small, vertical ink stamp on the right edge that reads “54027” on the postal tape that secures the left, right, and bottom edges. The envelope was ripped open by the recipient, extending to a closed tear across the flap. There is an additional circular stamp and several partial stamps on and just below the envelope flap.

Gerald Walton Hobson (1873-1962), the recipient of this letter, was with Robert Grenfell’s 12th Lancers during the Boer War and later wrote a history of the regiment. He was a polo player and steeplechase rider and plausibly knew Churchill through the commonalities of being cavalry officers with an interest in polo. Both Robert Grenfell and his brothers played polo during their military service.

The letter and envelope are now each protected within their own clear, removable, archival sleeves, these housed in a rigid crimson cloth folder.

By 1898, at the age of 23, Churchill had already demonstrated an eagerness to prove his mettle under fire and a facility not only for combat, but also for engaging with an audience as a well-compensated war correspondent. Attaching himself to General Bindon Blood’s punitive expedition on the northwest Indian frontier in 1897 had resulted in both his being mentioned in dispatches for “courage and resolution” and impetus to publish his first book – The Story of the Malakand Field Force – based on his dispatches to the Daily Telegraph and the Pioneer Mail.

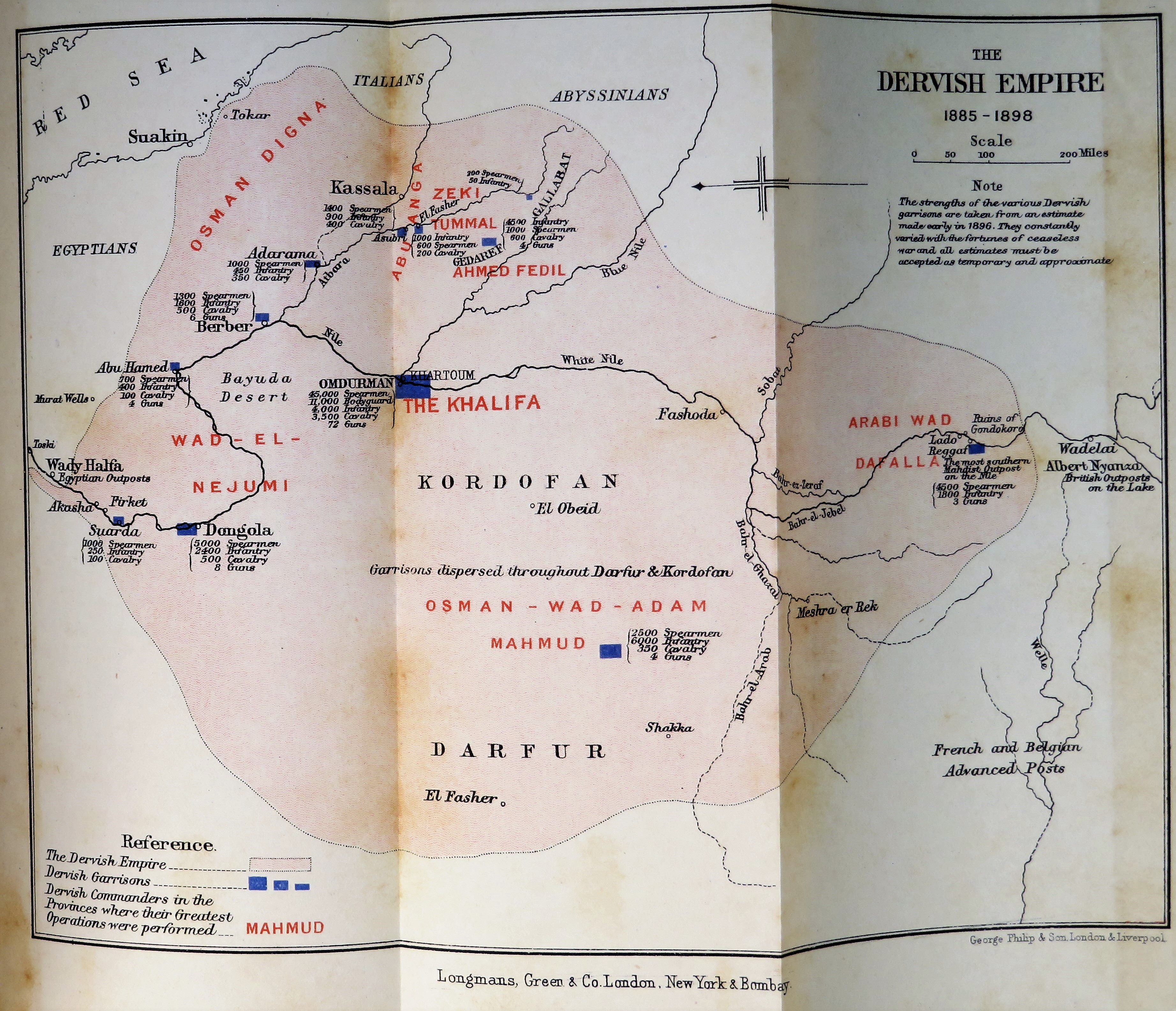

Far afield from India, a different colonial conflict loomed in Sudan. In 1883, forces of a messianic Islamic leader, Mohammed Ahmed, overwhelmed the Egyptian army of British commander William Hicks and Britain ordered withdrawal. In 1885, General Gordon famously lost his life in a doomed defense of Khartoum. Though the Mahdi died the same year, his theocracy continued. By 1898, the British government was finally ready to send an Anglo-Egyptian expedition and it fell to Major-General Sir Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) “to exact revenge and protect the southern part of British-controlled Egypt.”

Churchill was “desperate to fight in the coming Sudan campaign” and pleaded with his well-connected and influential mother to help secure him a place with Kitchener’s expedition. This was no small task as “both Kitchener and Douglas Haig, his staff officer, were totally opposed to having journalists on the expedition, especially one as thrusting and high-profile as Churchill”. Kitchener – quite rightly it turned out – was wary of Churchill’s “reputation for criticizing generals in print.” Even appeal from Prime Minister Salisbury on Churchill’s behalf via the High Commissioner in Egypt did not sway Kitchener. In the end, Churchill secured a posting as a supernumerary lieutenant attached to the 21st Lancers only through the appeal of the wife of a family friend – and this only because a Lieutenant had died, creating a vacancy.[iii] Churchill was ordered to regimental headquarters in Cairo, but told by the War Office “It is understood that you will proceed at your own expense and that in the event of your being killed or wounded… no charge of any kind will fall on British Army funds.”[iv]

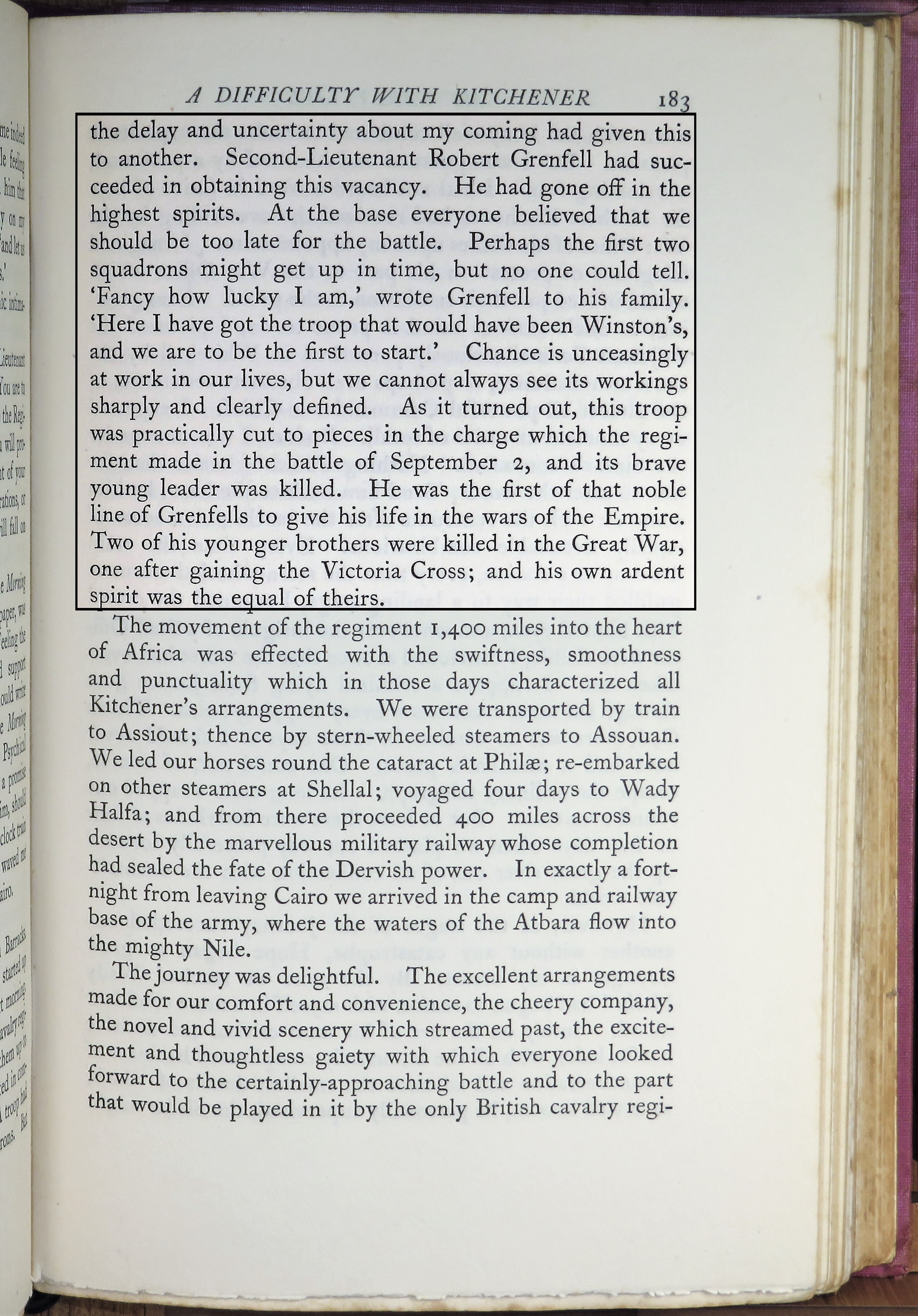

Churchill hastened to Egypt, where a troop had been reserved for him “in one of the leading squadrons” but a delay and uncertainty about his arrival meant that his position had been given to another – Second Lieutenant Robert Grenfell. “‘Fancy how lucky I am,’ wrote Grenfell to his family. ‘Here I have got the troop that would have been Winston’s, and we are to be the first to start.’”[v]

Lieutenant Robert Septimus Grenfell (1875-1898) was the brother of Colonel Cecil Alfred Grenfell (1864-1924) who married Lady Lilian Maud Spencer-Churchill (1873-1951), Winston’s cousin, in 1898. Robert and his eight brothers heeded their family’s distinguished military pedigree. Their maternal grandfather was Admiral John Pascoe Grenfell and their uncle Field Marshal Francis Grenfell, 1st Baron Grenfell.

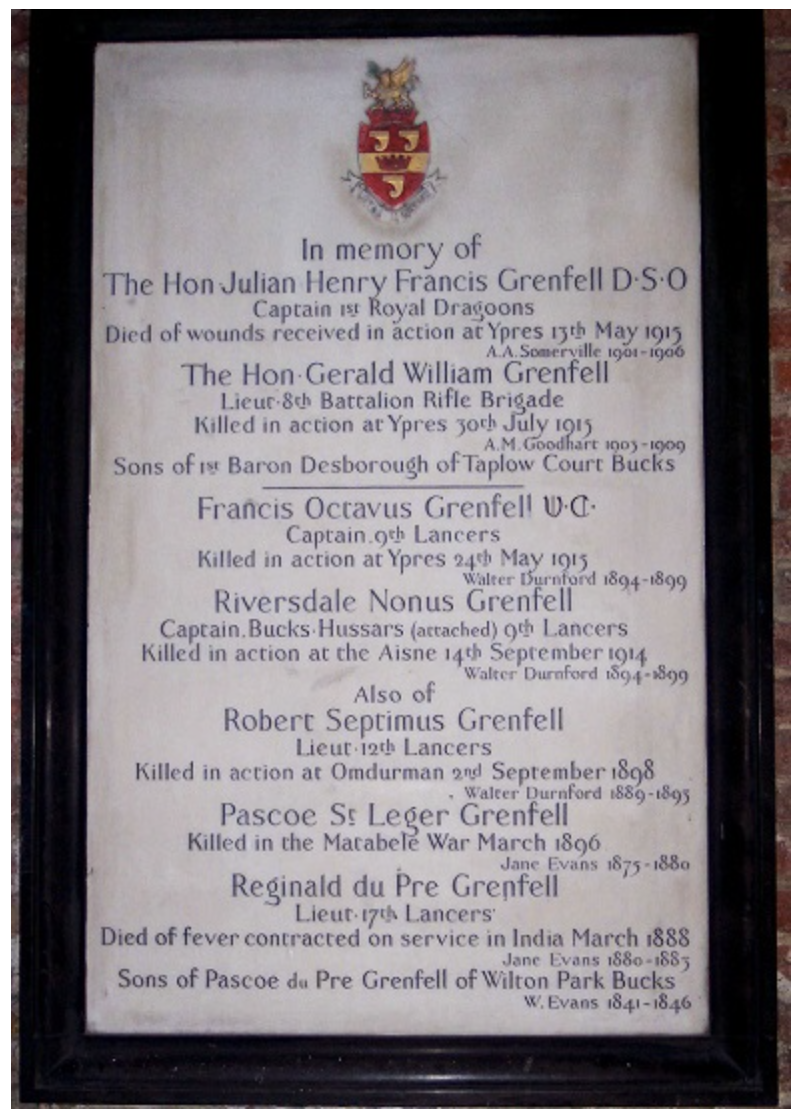

Robert’s generation of Grenfells gave extravagantly to the Empire. Three of Robert’s brothers (Cecil Alfred, Howard Maxwell, and Arthur Morton Grenfell) reached the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the British Army. Arthur married the daughter of General Sir Neville Lyttleton, who served under and succeeded Kitchener in command in South Africa. One of Robert’s brothers, as well as a cousin, would die in the Boer War and both of Robert’s younger twin brothers, Francis and Riversdale, were killed in the First World War. Two other cousins – the poet Julian Grenfell and his brother Gerald, also fell during the First World War. But first of his generation of Grenfells to fall was Robert, who quite mistook “how lucky I am”.

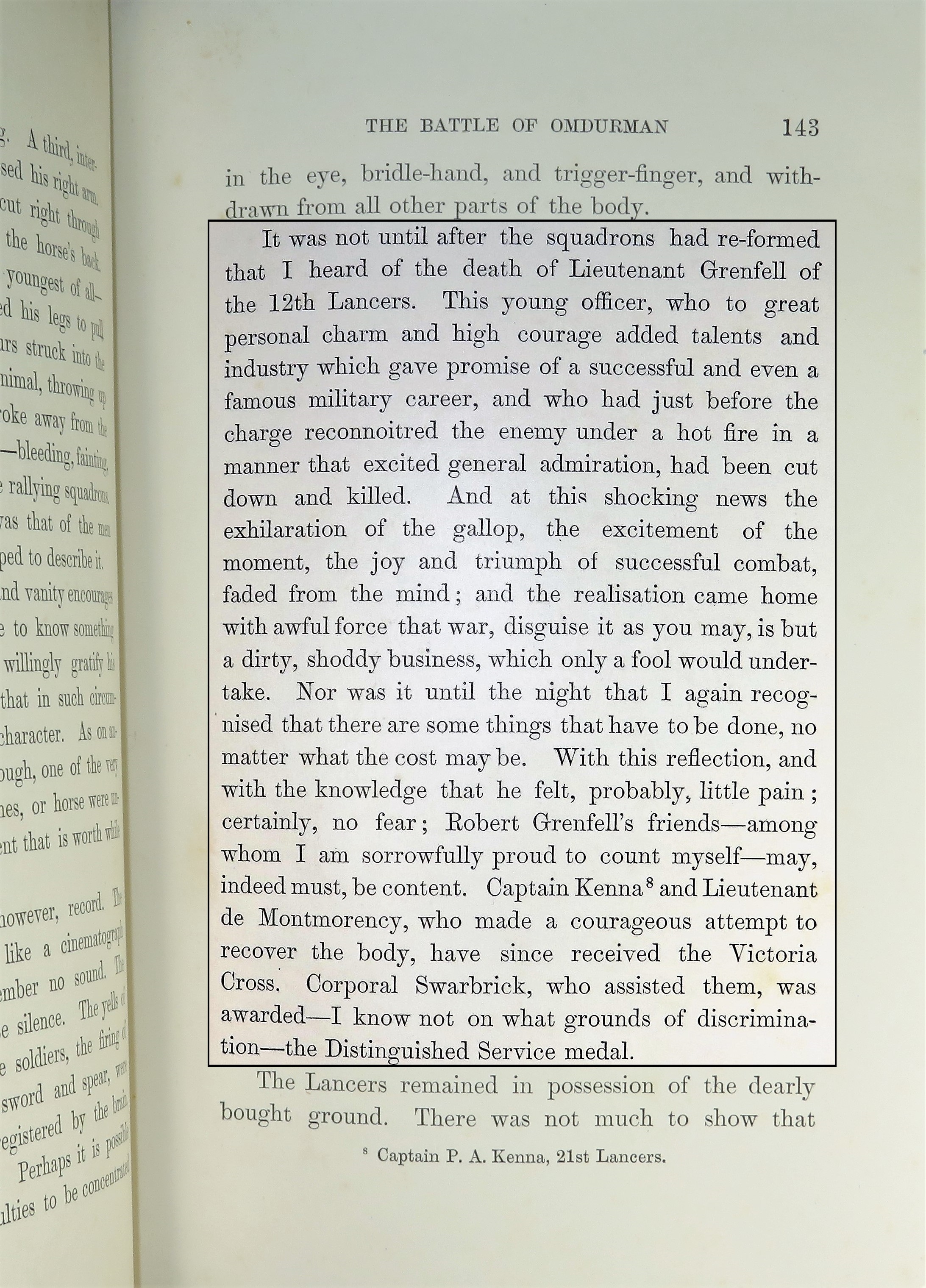

On 2 September 1898, during the Battle of Omdurman, Grenfell was literally hacked to pieces by the Mahdist forces. Churchill later wrote “…at this shocking news, the exhilaration of the gallop, the excitement of the moment, the joy and triumph of successful combat, faded from the mind; and the realisation came home with awful force that war, disguise it as you may, is but a dirty, shoddy business, which only a fool would undertake. Nor was it until the night that I again recognised that there are some things that have to be done, no matter what the cost may be.”[vi]

This was no affected recollection, but closely mirrors Churchill’s initial response when he wrote to his mother just two days after the battle about “poor Grenfell” whose death “took the pleasure and exultation out of the whole affair, as far as I was concerned.” In that letter, Churchill told his mother that he spent the night after the battle “anxious and worried” speculating on the “shoddiness of war.”

The visceral sense of war’s stark brutalities and fateful chances that Grenfell’s death imparted lingered. On 29 September Churchill wrote to his first cousin “Sunny” (Charles Marlborough, 9th Duke of Marlborough) “It is good to be able to look out on life again, without the feeling that perhaps death impended in the near future. I should have hated to lie in that hot red sand at Omdurman-after all the army had marched away. And yet on what do these things depend. Chance-Providence-God-the Devil-call it what you will. Had I started when I meant to from London I should have had Grenfell’s troop and ridden where he rode. I could not get a place in the sleeping car and delayed two days.”[vii] Thirty-two years later, in his autobiography, Churchill was still reflecting on Grenfell’s death, and wrote of the incident “Chance is unceasingly at work in our lives, but we cannot always see its workings sharply and clearly defined.”[viii]

For the rest of his life, Churchill conspicuously chanced and dared – with both his reputation and his life – but he would also seek to bend the vagaries of chance to his will and perspective. In this, his pen proved a far more formidable weapon than the horse and pistol that had seen him through the cavalry charge at Omdurman.

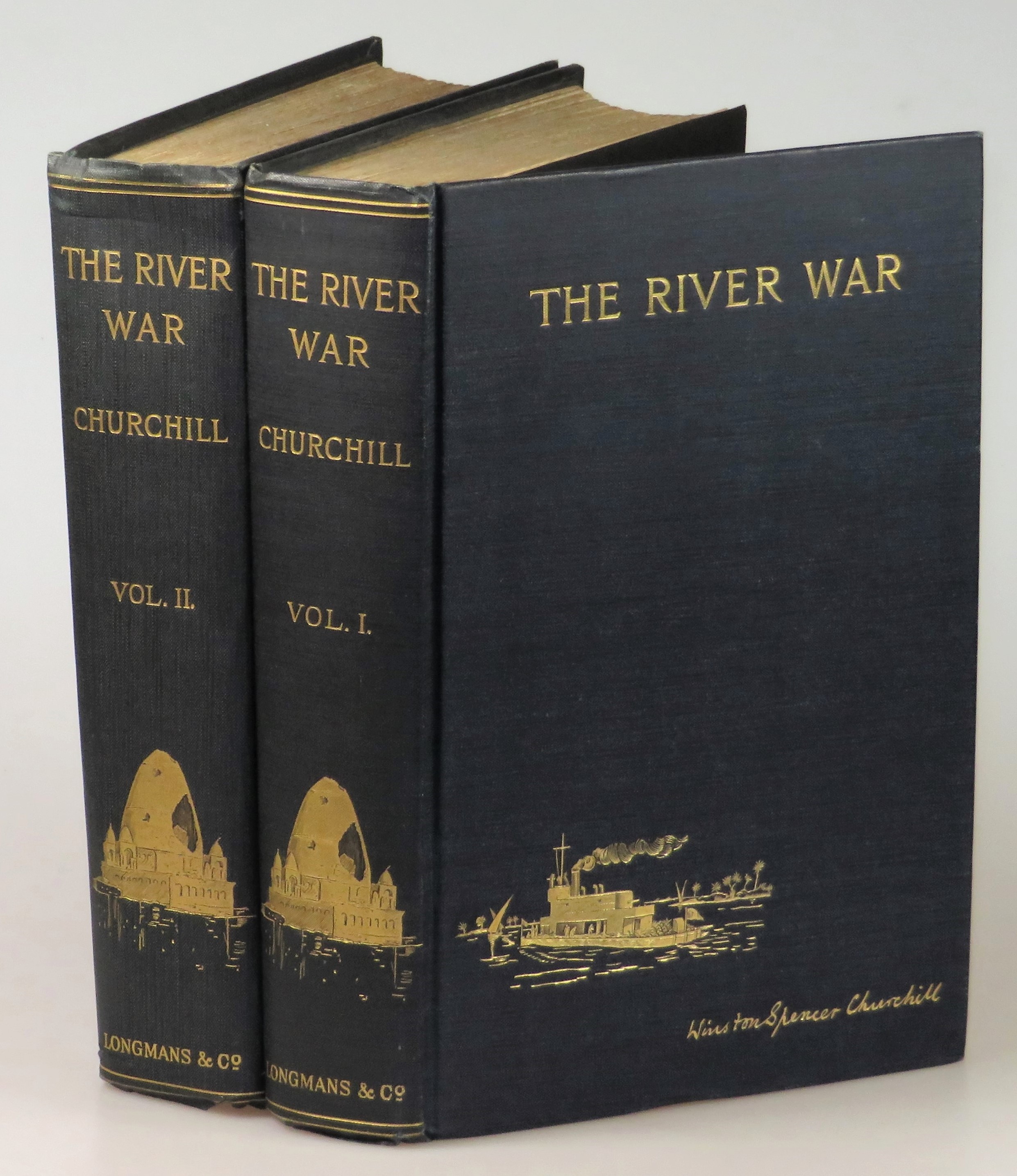

To the point, half a century after Omdurman, Churchill told the House of Commons “I consider that it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.”[ix]Churchill could not save his friend and comrade from death, but he could defend his reputation. When he published his account of the British campaign in the Sudan (The River War, November 1899), he gave Grenfell the posthumous gift of favorably written history. Before the battle, Grenfell was sent out at the head of a patrol “to see what the ground looked like from further along the ridge and on the lower slopes of Surgham.” Churchill watched Grenfell and his Lancers galloping back from this patrol under rifle fire “followed last of all by their officer, who looked, I remember thinking at the time… the beau-ideal of the cavalry subaltern.” Grenfell’s patrol reported a force “of Dervishes about 1,000 strong.” Churchill contends in The River War that Grenfell was not wrong, but rather that the Dervish force was reinforced after his patrol, increasing to 2,700. Either way, an attack was ordered based on Grenfell’s intelligence and the cavalry regiment – including both Grenfell’s 12th Lancers and Churchill’s 21st Lancers – confronted a force considerably larger than expected.

During the first charge, “In 120 seconds five officers, 65 men, and 119 horses out of less than 400 had been killed or wounded.”[x] Grenfell’s own troop “was practically cut to pieces in the charge which the regiment made… and its brave young leader was killed.”[xi] Churchill is anything but neutral and detached in conveying the loss. “This young officer, who to great personal charm and high courage added talents and industry which gave promise of a successful and even a famous military career, and who had just before the charge reconnoitered the enemy under a hot fire in a manner that excited general admiration, had been cut down and killed.”[xii]

Churchill stayed in touch with members of the Grenfell family, including dining with Robert’s younger twin brothers Francis and Riversdale and attending Francis’s funeral when he was killed during the First World War, days after Churchill was forced to resign his post as First Lord of the Admiralty.

It is noteworthy that Churchill’s book, a thoroughly edited and carefully considered work published more than a year after the events it describes – nonetheless uses some of the very same language to describe Grenfell employed in Churchill’s September 1898 letter describing Grenfell to Hobson. It seems reasonable to take this as further evidence of the enduring impact of Grenfell’s death on Churchill.

Of course, no single battle and single death can fully encapsulate or encompass a man like Churchill. Neither can a single letter illuminate the full complexity of his vast experience and perspective. Just the same, it is impossible not to regard this letter as testimony to a fundamentally formative loss that informed Churchill’s notions of war, courage, fortune, and fate for the rest of his life.

We will offer this remarkable letter for sale on 4 June 2020.

Cheers!

Marc Kuritz

[i] Gilbert. Vol. VII, p.506

[ii] WSC, letter to Lady Randolph, 4 September 1898

[iii] Roberts, Walking with Destiny, p.53-4

[iv] WSC, My Early Life, p.182

[v] WSC, My Early Life, p.183

[vi] WSC, The River War p.143

[vii] Letter held by the Library of Congress

[viii] WSC, My Early Life, p.183

[ix] Speech of 23 January 1948

[x] WSC, The River War, pp.132-143

[xi] WSC, My Early Life, p.183

[xii] WSC, The River War, p.143