Why? It seems reasonable to ask. When an author leaves behind volumes of published work, what compels our attention to their mere correspondence? We write today to share an intriguing letter by T.E. Lawrence that helps answer the question.

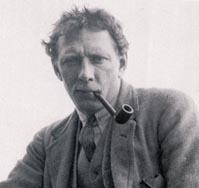

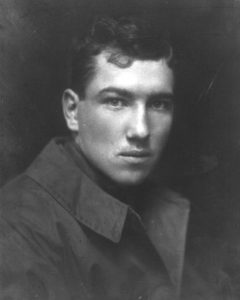

Central to the life story of T. E. Lawrence (1888-1935) is his military odyssey in Arabia during the First World War. There he found fame as instigator, organizer, hero, and tragic figure of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence began the First World War as an eccentric junior intelligence officer and ended as “Lawrence of Arabia.” This time defined Lawrence with indelible experience and celebrity which he would spend the rest of his famously short life struggling to reconcile and reject, to recount and repress.

However, Lawrence’s literary and intellectual reach far exceeded the world and words of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Lawrence’s friend and admirer Winston Churchill said: “Lawrence had a full measure of the versatility of genius… He was a savant as well as a soldier. He was an archaeologist as well as a man of action. He was an accomplished scholar as well as an Arab partisan. He was a mechanic as well as a philosopher. His background of somber experience and reflection only seemed to set forth more brightly the charm and gaiety of his companionship, and the generous majesty of his nature.” (Great Contemporaries, p. 166)

However, Lawrence’s literary and intellectual reach far exceeded the world and words of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Lawrence’s friend and admirer Winston Churchill said: “Lawrence had a full measure of the versatility of genius… He was a savant as well as a soldier. He was an archaeologist as well as a man of action. He was an accomplished scholar as well as an Arab partisan. He was a mechanic as well as a philosopher. His background of somber experience and reflection only seemed to set forth more brightly the charm and gaiety of his companionship, and the generous majesty of his nature.” (Great Contemporaries, p. 166)

Personal correspondence is ephemeral, unpolished, and personal in a manner fundamentally different than published literary works. Perhaps that is precisely why the brilliant, complex, and deeply conflicted facets of Lawrence’s character often glint most tantalizingly in his personal correspondence.

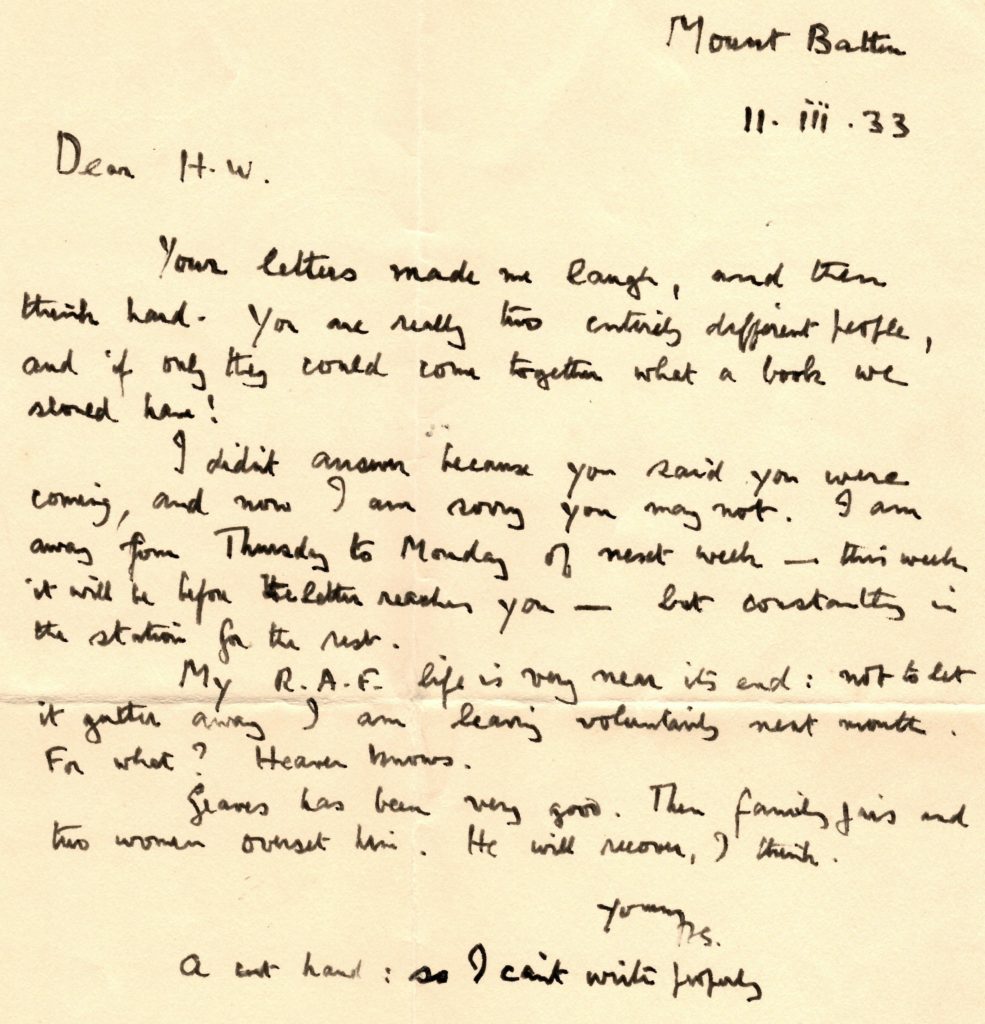

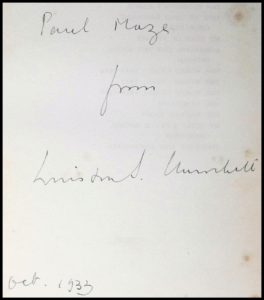

To the point is an original, autograph signed letter dated 2 March 1933 from T. E. Lawrence to his friend and fellow writer Henry Williamson. A mere 125 words long, the letter is nonetheless rich in both references and inferences. Penned at Mount Batten R.A.F. station, the letter is a window into Lawrence’s friendship with Williams, as well as his friendship with writer Robert Graves, and references Lawrence’s angst about ending his R.A.F. career. The letter also eerily presages correspondence regarding meeting with Williamson that would inadvertently precipitate Lawrence’s death a little more than two years later.

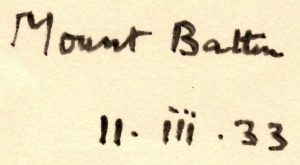

The letter is headed: “Mount Batten | II.iii.33”.

“Mount Batten” was a Royal Air Force station and flying boat base at Mount Batten, a peninsula in Plymouth Sound, Devon, England. A “small and isolated” station and “one of the most enjoyable of Lawrence’s postings.” (Wilson, Lawrence, p.850)

Lawrence himself described it as “about 100 airmen, pressed tightly on a rock half-awash in the Sound; a peninsula really, like a fossil lizard swimming from Mount batten golf-links across the harbor towards Plymouth town. The sea is thirty yards from out hut one way, and seventy yards the other.” (Letter of 20 March 1929)

Lawrence himself described it as “about 100 airmen, pressed tightly on a rock half-awash in the Sound; a peninsula really, like a fossil lizard swimming from Mount batten golf-links across the harbor towards Plymouth town. The sea is thirty yards from out hut one way, and seventy yards the other.” (Letter of 20 March 1929)

Lawrence writes:

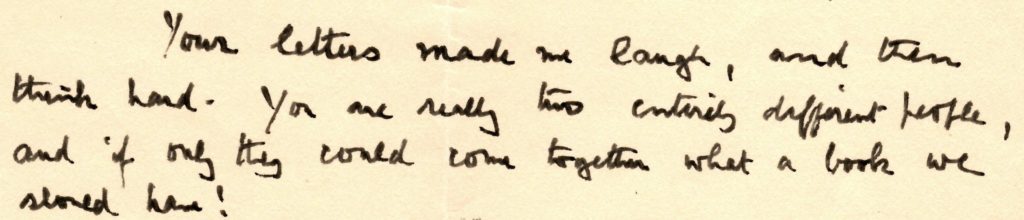

“Dear H. W. | Your letters made me laugh, and then | think hard. You are really two entirely different people,| and if only they could come together what a book we | should have!”

“H. W.” is the English writer Henry William Williamson (1895-1977). The “You really are two entirely different people, and if only they could come together…” comment is fascinating. Williamson was “a skillful and supremely observant writer, but nevertheless a man who was introspective, egocentric, insecure, and intensely lonely” – words which could easily be used to characterize Lawrence himself. This is not an incidental parallel. It is interesting that Lawrence’s official biographer, Jeremy Wilson, also observed that from Williamon’s letters “it seems to me that Williamson allowed reality and fantasy to intermingle in his everyday thinking. When that happened, the first casualty… was often the truth. Nevertheless, there were other times when he could write with disarming honesty and self-criticism.” (Wilson, T.E. Lawrence Correspondence with Henry Williamson, p.xii)

When Lawrence read Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter in 1928, he recognized that its author had extraordinary descriptive power: ‘I put Williamson very high as a writer,’ he later wrote. From this beginning grew a significant correspondence that lasted until Lawrence’s death in 1935. “While the two were different in so many ways, the similarity that Williamson sensed was real. He was writing to someone he could understand.” Williamson damaged the relationship in 1933 by including Lawrence, unasked, as a character called ‘G.B. Everest’ in The Gold Falcon – even quoting from his letters. Though Lawrence made light of it, his uneasy relationship with publicity and the need to avoid it in order to remain in the R.A.F. ranks put constraints on the friendship. Williamson’s disclosure of acute emotional distress associated with extra-marital entanglements did not help matters. But “Despite these reservations, there really was an unusual quality in their relationship.”

When Lawrence read Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter in 1928, he recognized that its author had extraordinary descriptive power: ‘I put Williamson very high as a writer,’ he later wrote. From this beginning grew a significant correspondence that lasted until Lawrence’s death in 1935. “While the two were different in so many ways, the similarity that Williamson sensed was real. He was writing to someone he could understand.” Williamson damaged the relationship in 1933 by including Lawrence, unasked, as a character called ‘G.B. Everest’ in The Gold Falcon – even quoting from his letters. Though Lawrence made light of it, his uneasy relationship with publicity and the need to avoid it in order to remain in the R.A.F. ranks put constraints on the friendship. Williamson’s disclosure of acute emotional distress associated with extra-marital entanglements did not help matters. But “Despite these reservations, there really was an unusual quality in their relationship.”

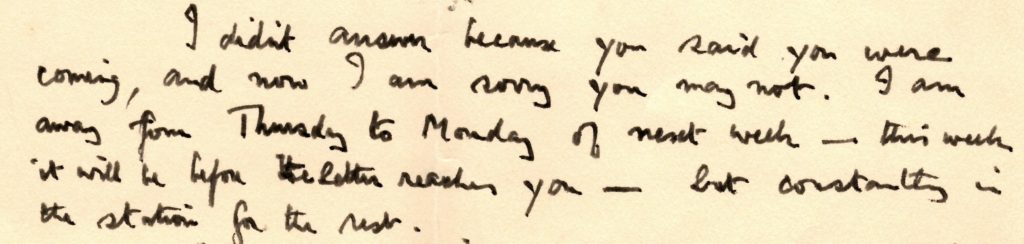

“I didn’t answer because you said you were | coming, and now I am sorry you may not. I am | away from Thursday to Monday of next week – this week | it will be before the letter reaches you – but constantly in | the station for the rest.”

It is eerie and fascinating to note that Lawrence’s correspondence with Williamson inadvertently precipitated Lawrence’s death. On 11 May 1935 Lawrence received a letter from Williamson proposing to call at Clouds Hill. “the only way Lawrence could be sure of getting a reply to Devon before Williamson set out was to send a telegram.” In mid-morning of 13 May, Lawrence rode his Brough to the post office at Bovington Camp and sent a wire to Williamson. On the way back to his cottage he suffered the accident that put him in a coma and, six days later, took his life. (Wilson, Lawrence, p.934)

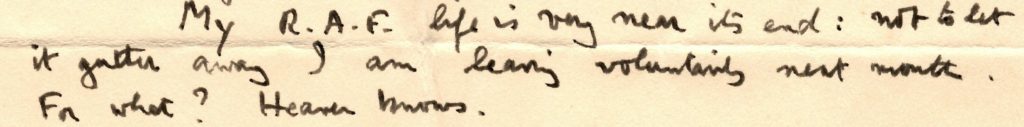

“My R.A.F. life is very near its end: not to let | it gutter away I am leaving voluntarily next month. | For what? Heaven knows.”

“My R.A.F. life is very near its end: not to let | it gutter away I am leaving voluntarily next month. | For what? Heaven knows.”

In a state of nervous exhaustion following the First World War, his work on the post-war settlement, and writing and re-writing Seven Pillars of Wisdom, in 1922, Lawrence enlisted in the ranks of the R.A.F. under the name of John Hume Ross. Lawrence’s time with the R.A.F. proved remarkably revealing – of his talents, both literary and technical, and of the dynamic tension in his life between his need for quiet anonymity and his fame and engagement with the famous.

It is telling that The Mint, Lawrence’s unstintingly candid portrait about life in the Royal Air Force Ranks, paralleled Seven Pillars – with a tortuous writing, editing, and publishing history culminating in posthumous publication.

Lawrence’s celebrity – and perhaps, as well, his own conflicted feelings about his fame – was a constant threat to his R.A.F life. Though Lawrence references “next month”, he actually submitted his formal request for discharge on 6 March 1933, just four days after he wrote this letter to Williamson: “I, No.338171 A/C Shaw, E., respectfully request that I may be granted an interview with the Commanding Officer, to ask him to forward my application to be released from further service in the Royal Air Force as from the sixth of April, 1933.” The request was granted (though on 19 April Lawrence withdrew his discharge application when offered a posting to the RAF Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe, where he was again able to work on RAF boats.)

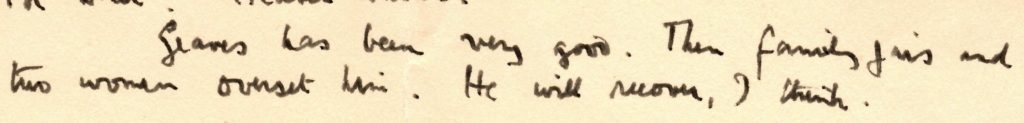

“Graves has been very good. Then family jars and | two women overset him. He will recover, I think.”

“Graves” is Robert von Ranke Graves (1895-1985), the English poet and novelist, with whom Lawrence had a difficult relationship at this time, owing in no small part because of Graves’s romantic relationship with the writer Laura Riding (1901-1991). The reference to Graves indicates Lawrence’s complicated and uncomfortable relationship with sexuality. Lawrence’s official biographer, Jeremy Wilson, confirms Lawrence’s feelings about Laura Riding: “Lawrence disliked Laura Riding intensely.” Wilson also confirms that the root of Lawrence’s dislike was sexual: Lawrence “felt that both of them had allowed their lives to be dominated by carnality”. (Wilson, Lawrence, p.870) Lawrence had written of the couple in a 1929 letter: “I cannot have patience with people who tickle up their sex until it seems to fill all their lives and bodies.”

“Graves” is Robert von Ranke Graves (1895-1985), the English poet and novelist, with whom Lawrence had a difficult relationship at this time, owing in no small part because of Graves’s romantic relationship with the writer Laura Riding (1901-1991). The reference to Graves indicates Lawrence’s complicated and uncomfortable relationship with sexuality. Lawrence’s official biographer, Jeremy Wilson, confirms Lawrence’s feelings about Laura Riding: “Lawrence disliked Laura Riding intensely.” Wilson also confirms that the root of Lawrence’s dislike was sexual: Lawrence “felt that both of them had allowed their lives to be dominated by carnality”. (Wilson, Lawrence, p.870) Lawrence had written of the couple in a 1929 letter: “I cannot have patience with people who tickle up their sex until it seems to fill all their lives and bodies.”

The other of the “two women” referenced is likely Nancy Nicholson, Graves’s wife; the three had untenably cohabitated until the menage was upended and Nicholson was left to raise her and Graves’s children alone.

Equally of note, in 1934 Lawrence was similarly put off by Williamson’s emotional disclosure about romantic entanglements.

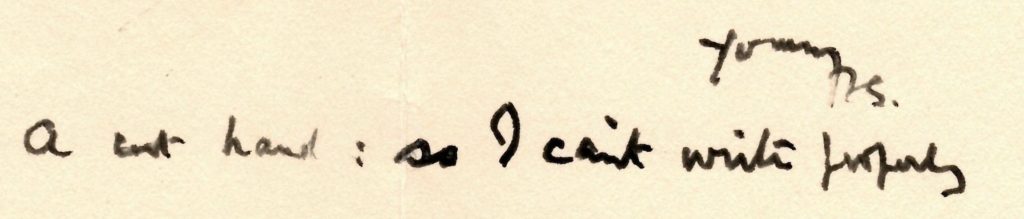

“A cut hand: so I can’t write properly.”

“A cut hand: so I can’t write properly.”

It is difficult to just take the postscript literally and not to regard the metaphor for a man who was as brilliant, gifted, and accomplished as he was damaged, confined by his own demons and ultimately cut short in both life and letters.

We offer this letter for sale HERE.