A few months ago, just before Christmas, I lost a friend and the Churchill world lost an erudite scholar.

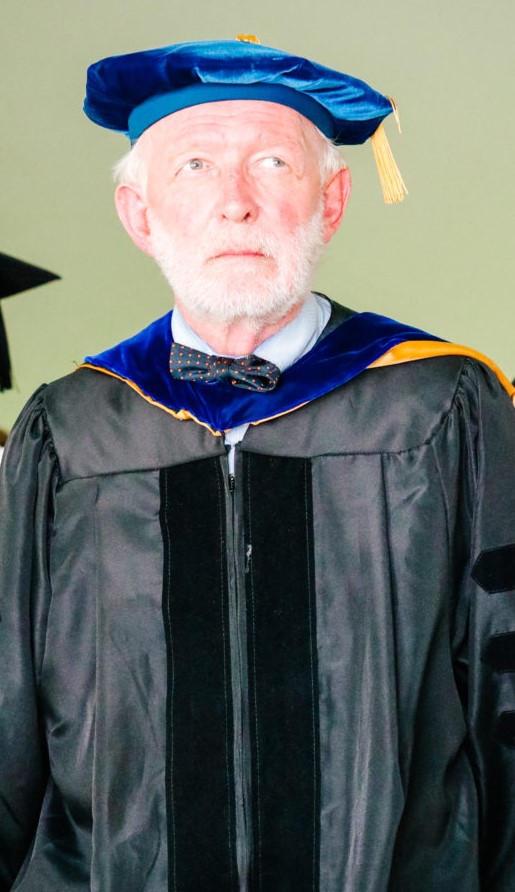

Patrick Powers spent more than half a century teaching at various Catholic colleges in New England. He leaves a wife and sons, relatives and friends and colleagues, but, perhaps most of all, students. So many students, whom he engaged and provoked, challenged and inspired.

Among Patrick’s admirers, there are many more capable of writing traditional obituaries, which have already been composed and read. What I wish to say here about Patrick, I say as a friend.

I learned of Patrick’s bleak and imminent prognosis not many days after he did, on 13 December. I was planning to visit him in January and pestering him for approval of dates. Annoyingly, he was not answering. After a few days of my prodding, he responded, uncharacteristically via text, and shared his terrible news. He may be the only person I know who could tell me both that he just learned he is dying and that he is “Grateful for everything” in the same message.

We argued, Patrick and I. Constantly. With vigor, pointedly, and with the edge-of-insult directness that two intellects who love to argue and truly regard one anther can apply without worrying about offense. I loved him for it. It was our habit to announce at the beginning of a phone call whether we were constrained for time, since we both knew that phone calls would otherwise last and wend far beyond whatever pretext prompted them.

When I learned he was dying, it hit me that I had argued with my friend for the last time. I confess to a terrible selfishness; this, more than anything, truly left me feeling bereft. Later that day, I wrote to Patrick’s wife some of what I share in this post. It took me some hours to find words. This made me laugh out loud, because I knew that Patrick would have relished my being at an uncharacteristic loss for words.

Regarding faith, I like to think I had a sense of what Patrick believed. And he knew what I did not believe. If we could speak again, I would tell him that he now has the opportunity to settle the question for us. I would ask him if he might do me the courtesy of letting me know what he has found and how he finds it. He would likely tell me to find faith and stop simply looking for answers.

Here’s what I know – and what I hope he knows/knew (as the metaphysical case may be). I expect Patrick is unable to tally the number of minds he has touched and kindled, prodded and provoked. This is a worthy legacy. This, and the ripple effects, are a quietly sublime and worthy immortality, irrespective of any other.

It is no accident that the night before he died, Patrick was grading the work of his students. And, of course, in his final days, he was still refining his thoughts on exhaustively interpreting Churchill’s Savrola. We should all hope that his efforts – at last review, a prologue and epilogue that threaten to exceed the actual text – see publication.

I told Patrick’s wife, Mary Ann, that this infidel won’t insult Patrick by pretending to pray for him. But I did wish him as peaceful, swift, and merciful a journey as the difficult circumstances permitted. And this he had. I am grateful for that, as for many other things.

If we were able to joyfully, vehemently argue today, as we did so many times, I might just concede Patrick – just this one time – the last word. I might even prayerfully steeple my hands, as I once did as a boy in Catholic school, bow ever so slightly, and incline my head to him with a deferential-yet-definitely-also-sardonic smile. I’d also concede that he summed up matters between us well enough; I’m “grateful for everything” too.

Then, if he was really fishing for hagiography and praise, I’d hit his Catholic sensibilities with some Yiddish and call him a Mensch. For so he was.

Godspeed, Patrick.