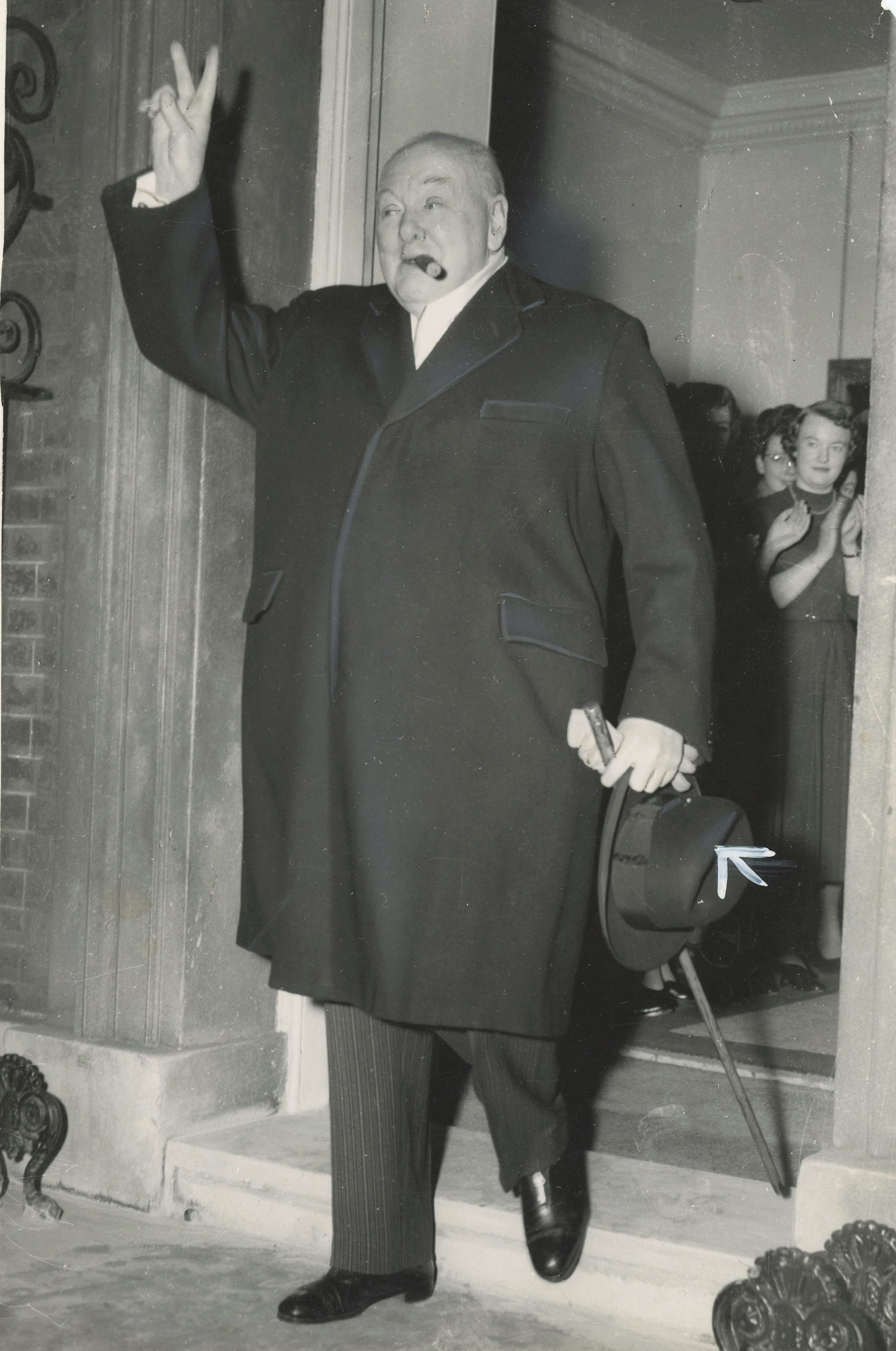

We recently had the privilege of spending some time with a compelling inscribed Churchill book – a British first edition of The World Crisis: The Aftermath. The story is one worth telling. Hence this post.

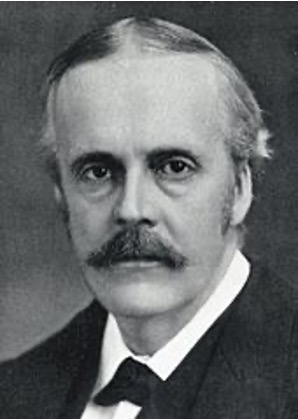

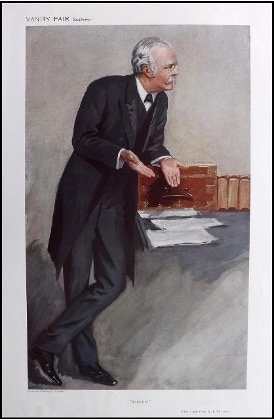

The Aftermath is the penultimate volume of Churchill’s history of the First World War. This particular copy is inscribed and dated to Arthur James Balfour, the man who replaced Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty when Churchill was forced to resign in 1915, who was Prime Minister when Churchill dramatically repudiated the Conservative Party in 1904, and beside whom Churchill worked in both Coalition and Conservative Governments of the 1920s. Of course, Churchill’s own words testify most eloquently to his association with Balfour, which both included and exceeded that of a colleague, mentor, or rival: “…this remarkable man whom I knew, and whose friendship, across the vicissitudes of politics, I enjoyed in a ripening measure during thirty years.” (WSC, Great Contemporaries, p.240)

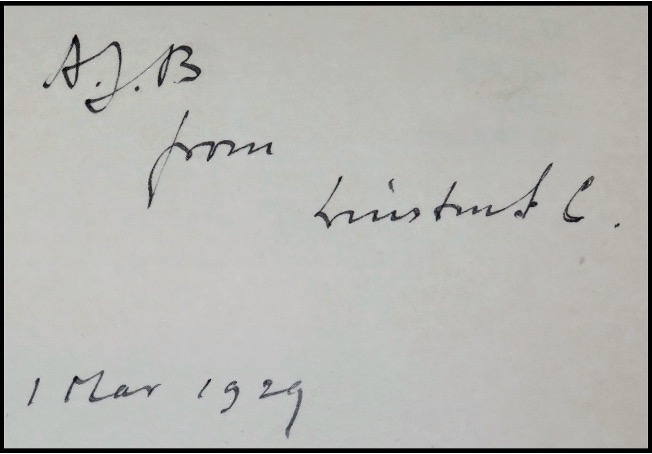

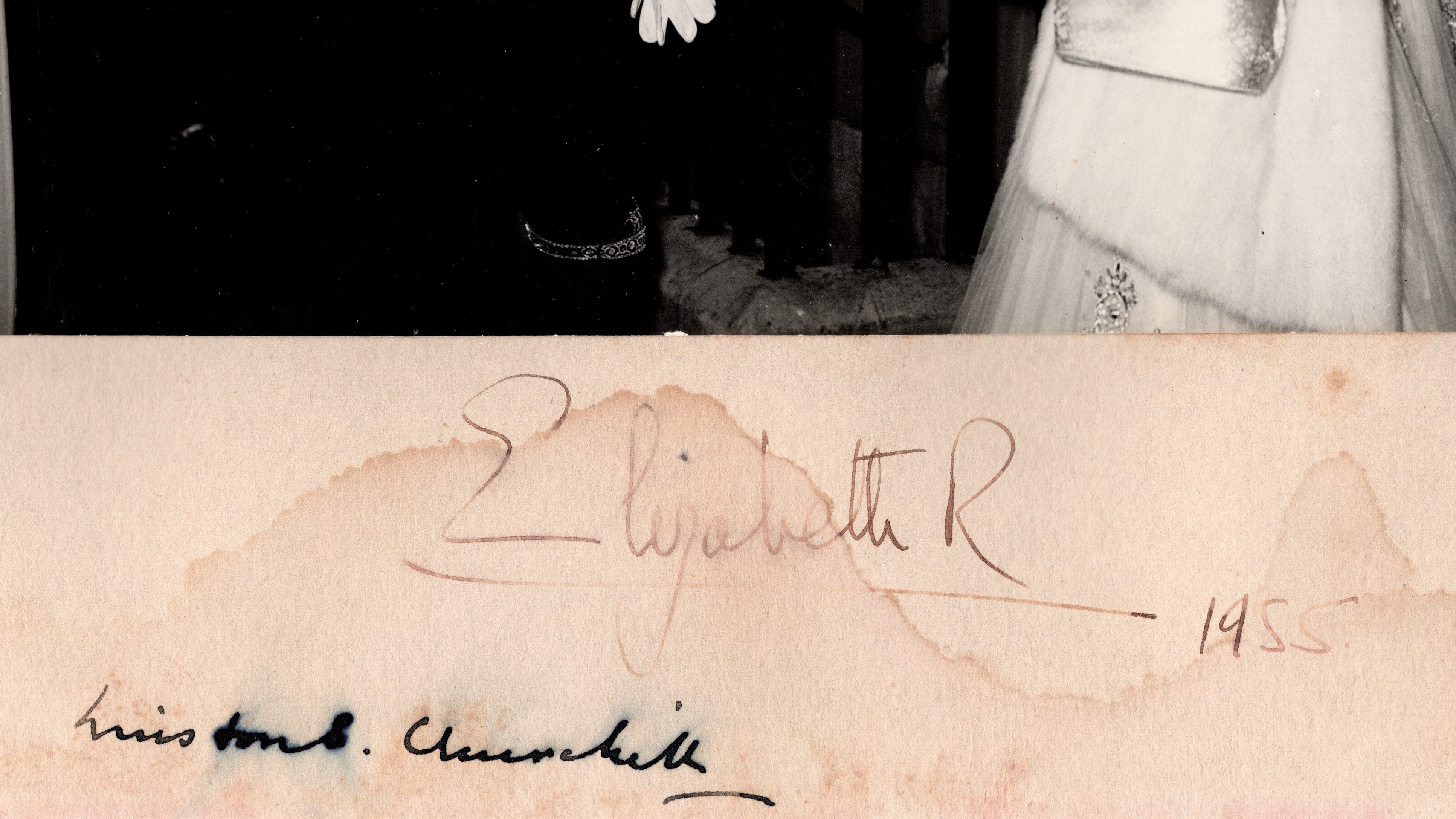

The inscription

Churchill inscribed this presentation copy of the first edition six days prior to publication. Using their respective initials, the tone is familiar, befitting their long association, and the first and third lines have a hint of playful versification – almost certainly intentional from a seasoned wordsmith like Churchill. Inked in four lines, the blank sheet recto preceding the half title reads:

A. J. B

from

Winston S. C.

1 Mar 1929

This was the last book Churchill published during Balfour’s lifetime; Balfour died a year after Churchill inscribed this copy to him.

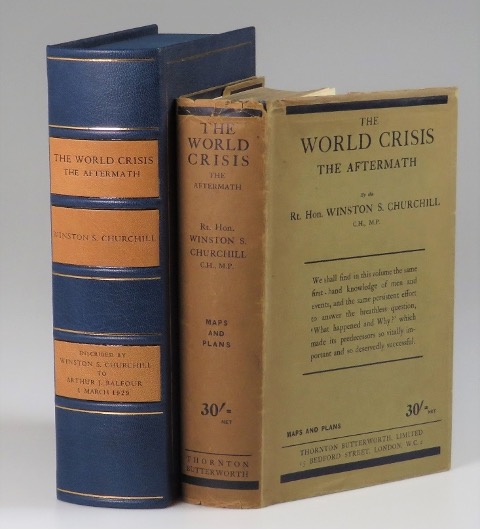

The edition

A quarter of a century before the Second World War endowed him with lasting fame, Winston Churchill played a uniquely critical, controversial, and varied role in the “War to end all wars”. Then, being Churchill, he wrote about it. The World Crisis was published in six volumes between 1923 and 1931. The first four volumes span the 1911-1918 war years, with two supplemental volumes. This fifth volume, The Aftermath, covers the postwar years 1918-1928 – a decade-long span during most of which Churchill and Balfour both served in high Government office.

The work has both literary and collector appeal – particularly jacketed first editions like this one. But those comparatively prosaic virtues are far eclipsed in this particular copy by the singular inscription and association.

The association

Arthur James Balfour, first Earl of Balfour (1848-1930) was among the most significant influences and associations of the first half of Churchill’s political career. The two were already tethered by friendship and politics when Winston was born, and during Winston’s first three decades in Parliament they were almost perpetually connected by oscillations of alignment and opposition, of concurrent and opposing political ascendance.

Balfour’s early education and preoccupation was philosophy, but in 1874 – the year Churchill was born – Balfour was elected to Parliament as a Conservative. There – notably opposite to Winston – his “lifelong antipathy to the physical process of handwriting” served him well, as it “led him to develop a remarkable ability to dictate lucid memoranda on complicated subjects.” This, coupled with the “habit of rationalistic discussion and debate that prevailed within his family circle”, contributed to Balfour’s formidable capacity for political debate.

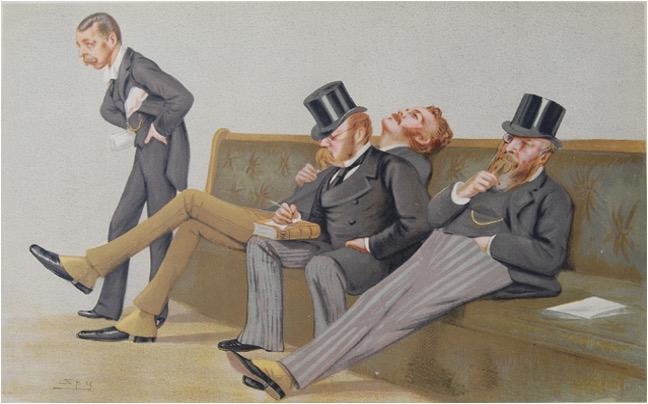

Balfour was friends with Winston’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill, and together with two other Conservative MPs they formed a “self-styled Fourth Party”, harrying and rebelling against their party leadership. However, Balfour’s inclination to rebellion proved less than that of either Randolph or Winston and Balfour eventually heeded loyalty to the Conservative Party. Indeed, by 1891 Balfour became First Lord of the Treasury and leader of the House of Commons. Balfour led his party – either in opposition or in Government – for two decades.

From his exalted position, Balfour supported Winston in his early endeavors. In 1897, it was Balfour who advised that young Winston entrust his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, to the literary agent A. P. Watt, who successfully made publication arrangements with Longmans on Winston’s behalf. (R. Churchill, Vol. I, p.367) When Churchill lost his first election, Balfour wrote to Winston “I had greatly hoped to see you speedily in the House… I hope… you will not be discouraged… this small reverse will have no permanent ill effect upon your political fortunes.” (letter of 10 July 1899) When Churchill ran again, this time as a famous hero of the Boer War, Balfour wrote encouragingly “I have great hopes that you will win the seat… you have had fresh opportunities – admirably taken advantage of – for shewing the public of what stuff you are made.” (letter of 30 August 1900).

Churchill won his first seat on 1 October 1900. Taking his seat in Parliament at the age of 26, Churchill was soon following family form, dissenting from, and fomenting backbench revolt against, the Conservative Party – ironically now led by Balfour. In late May 1904, during Balfour’s 1902-1905 premiership, young Winston dramatically left the Conservative Party and crossed the aisle to become a Liberal, swiftly earning a reputation as both a brash young radical and a traitor to his class. Indeed, the great political battle over The People’s Budget and the authority of the House of Lords – battles in which Winston proved such a powerful Liberal advocate – exacerbated the political pressures on the Conservatives. Hence young Winston the Liberal contributed to both electoral and parliamentary defeat of the Conservatives and to Balfour’s resignation as party leader in November 1911 – only weeks after Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty.

Arguably, Balfour’s most important legacies and most potent time in power came in the decades ahead, after he no longer formally led his party. Moreover, the First World War and its aftermath – apropos the title of the inscribed work in question – tethered Balfour and Churchill even more than had the preceding decades.

In 1911, Churchill pressed Prime Minister Asquith to make Balfour a permanent member of the Committee of Imperial Defence. (WSC, Great Contemporaries, p.255) Churchill’s efforts to dramatically enhance naval preparedness were supported by Balfour “who, though regarding an Anglo-German war as a virtual impossibility… saw the dominant need to maintain British naval supremacy.” (R. Churchill, Vol. II, p.571). In differing with Churchill over submarines, Balfour was more prophetically astute. “Balfour tried without success to get… Churchill, the first lord of the Admiralty, to appreciate that submarines were essentially the weapon of the weaker naval power; and in correspondence with Admiral Lord Fisher it was Balfour who pointed out that, if war should come, U-boats would probably sink British and other merchant shipping without restraint”. It is worth noting that Balfour would prove equally prophetic when, in his final time in office in 1928, “He also wanted additional spending on naval anti-aircraft weapons ahead of cruisers.” (ODNB) On both counts, Balfour anticipated the weapons that would revolutionize naval warfare in each world war – the submarine in the First and the aircraft in the Second.

On the Dardanelles, the strategic initiative that would end Churchill’s tenure at the Admiralty, the two men were in accord. Balfour had supported – indeed had “argued persuasively in favor” of – Churchill’s proposal to attack the Dardanelles with ships alone. (ODNB) When the Dardanelles disaster engulfed Churchill and forced his resignation, it was Balfour who succeeded Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty – to Churchill’s professed “great relief”. (Gilbert, Vol. III, p.468)

Churchill eventually resigned even his nominal Cabinet posts to spend the rest of his political exile as a lieutenant colonel leading a battalion in the trenches at the Front. Then came yet another dramatic political misstep, this one with Balfour at the center. Within days of his return to London from the Front in May 1916, despite this manifest support for Balfour succeeding him at the Admiralty, Churchill decided to publicly attack Balfour.

“Twelve years had passed since Churchill had last spoken in the House of Commons as the critic of a Government. Then, his had been the lance of youthful anger hurled, always with agility and sometimes with venom, against the Conservative Prime Minister, A. J. Balfour. It had seemed impudence for so young a Member of Parliament to attack the Leader of the ruling Party, from whose back benches he had only just migrated… When he rose to speak from the front opposition bench late in the afternoon of Tuesday 7 March 1916, it was with the accumulated experience of those twelve years behind him; but it was also with his credibility impaired by the controversies and disasters of the previous year. After twelve years, it was again A. J. Balfour whom he rose to attack.” Churchill assailed the efficacy and urgency of Balfour’s Admiralty administration. “The House of Commons had not heard such a strong indictment of a Government Department since the war began.” (Gilbert, Vol. III, p.716-718) In his attack, and in his prescription for righting the proverbial Admiralty ship, Churchill gravely miscalculated.

Even in his politically weakened state, Churchill’s defeat in debate was a notable occasion. Balfour’s memorable rebuttal, on 8 March 1916, of Churchill’s attack, brought Churchill to admit that Balfour was “a master of parliamentary sword-play and of every dialectical art” (Mackay, Balfour, 291). As Churchill would say years later of Balfour, “Whatever had to be said, he knew how to say it; and when others blundered into foolish or offensive remarks, he knew how to defend himself or retaliate with point, justice or severity.” (WSC, Great Contemporaries, p.241) This was singular praise coming from Churchill, and it is difficult not to speculate that Churchill had this particular occasion in mind. Perhaps Churchill also remembered – maybe with a touch of autobiographical admission – his bruising House of Commons altercations with Balfour when he framed Balfour’s memory thus: “I had the privilege of visiting him several times during the last months of his life… I felt… the tragedy which robs the world of all the wisdom and treasure gathered in a great man’s life and experience, and hands the lamp to some impetuous and untutored stripling…” (WSC, Great Contemporaries, pp. 241-257)

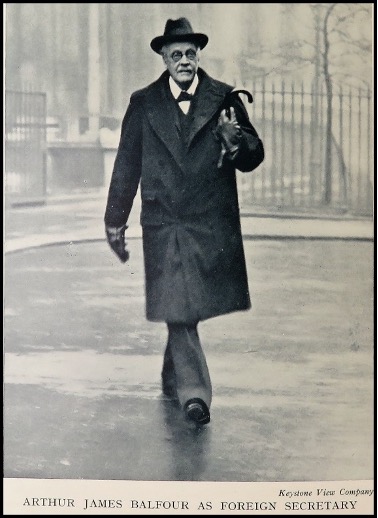

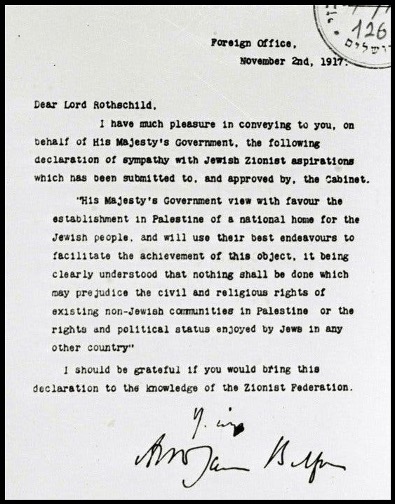

Balfour’s tenure at the Admiralty ended along with the end of Asquith’s premiership in December 1916. By the time of Churchill’s exoneration and return to the Cabinet as Minister of Munitions in mid-1917, Balfour was already serving as Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s Foreign Secretary. During Balfour’s tenure at the Foreign Office, Churchill would also serve as Secretary of State for War and for Air. Echoing the same resolution Churchill would show a quarter of a center later during the Second World War, Balfour “never swerved from insistence on the military defeat of Germany.” (ODNB) Also echoing the future Churchill, Balfour “had for long attached much importance to Anglo-American friendship” and did much to “smooth the way for American co-operation” in the war effort. Churchill would later say of him “Never has England had a more persuasive or commanding ambassador and plenipotentiary.” (WSC, Great Contemporaries, p.256) And it was the Balfour Declaration that formally stated that the British government supported “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” – an unequivocally Zionist position to which Churchill would also commit. As Churchill would later be to the genesis of the United Nations, Balfour was committed to the U.N.’s ill-fated forerunner, the League of Nations, serving as Lord President of the League’s Council from 1919-1922. Their final service together was in the government of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin; from 1925-1929, Balfour served as Lord President of the Council while Churchill served as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

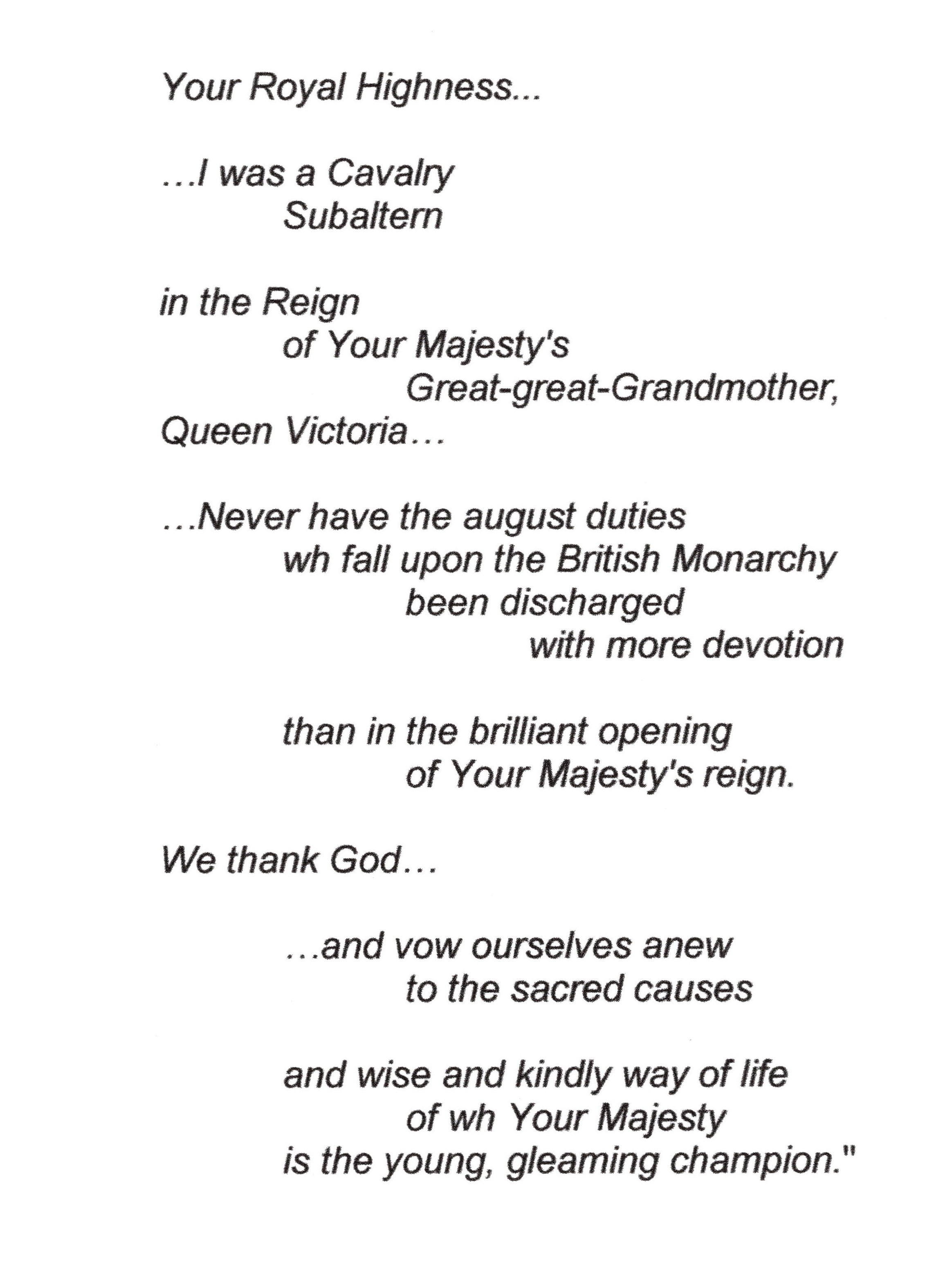

On 1 March 1929 – six days before publication – Churchill inscribed this volume for Balfour. In the autumn of 1928, ill-health had finally removed the octogenarian Balfour from active work. “Out of courtesy and respect” Baldwin insisted on his retaining his office until the 30 May 1929 general election brought the end of Baldwin’s government. Balfour died the next year. Churchill would not serve in a cabinet again until the outbreak of the Second World War, more than a decade later. In 1937, two years before the war that would see him finally ascend to the premiership and cement his own place in history, Churchill devoted an entire chapter of his book Great Contemporaries to Balfour, of whom Churchill wrote:

“He acquired and possessed from earlier life profound and definite conceptions; and by a marvelous gift of comprehension and receptivity he was able to adjust all the new phenomena and the ever-changing currents of events to his solidly-wrought convictions. His interest in life, thought and affairs… was as keen at eighty as it was at twenty: but his purpose, his foundation, and his main theme were obstinate, obdurate, and virtually unchanged throughout the memorable times in which he lived, played his part, and even ruled. He was a man to whom without commonplace extravagance one might apply the word ‘Statesman.’” (WSC, Great Contemporaries, pp.238-39)

It seems worth noting that Churchill’s incisive praise might apply as well to the author as to the subject, perhaps explaining the long association that spanned and survived “vicissitudes of politics”.