There’s been a fight among staff here at CBC.

There’s been a fight among staff here at CBC.

We’ve been hoarding a trove of signed and inscribed material. Some of us want to hold on until the end of the year for our forthcoming “Extra Ink” catalogue. Some of us don’t want to make our customers wait. Since we’re poor pugilists, we’ve compromised. We’ll reserve roughly 40 signed or inscribed items for the catalogue. But, over the coming months we will give you a sneak peek at some of these hoarded treasures in our blog posts.

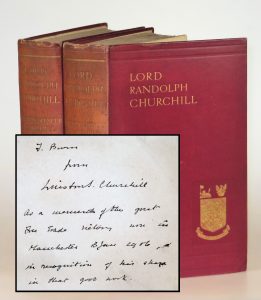

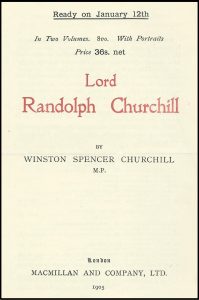

Today, we start early – 13 January 1906 to be precise – with a first edition presentation set of Lord Randolph Churchill inscribed to the man who guided Churchill’s successful first campaign as a Liberal.

Today, we start early – 13 January 1906 to be precise – with a first edition presentation set of Lord Randolph Churchill inscribed to the man who guided Churchill’s successful first campaign as a Liberal.

This copy of Churchill’s biography of his father features a remarkable eight-line inscription in black ink on the front free endpaper:

“F. Burn

from

Winston S. Churchill

As a memento of the great

Free Trade victory won in

Manchester 13 Jan 1906, &

in recognition of his share

in that good work.”

The recipient, Fred Burn (1860-1930) signed the Volume II front free endpaper and further inked “Fred Burn | from the author” on the blank recto preceding the half title.

The set’s virtue resides in testifying to the associations and machinations of Churchill’s early Parliamentary career. The volumes have aesthetic flaws endemic to the edition, but are nonetheless unrestored and sound. Each volume is housed in a blue cloth chemise nested within a custom quarter leather slipcase.

The set’s virtue resides in testifying to the associations and machinations of Churchill’s early Parliamentary career. The volumes have aesthetic flaws endemic to the edition, but are nonetheless unrestored and sound. Each volume is housed in a blue cloth chemise nested within a custom quarter leather slipcase.

You probably have not heard of Fred Burn for a reason; he was the kind of behind-the-scenes political figure who pins the hinges of electoral power but remains substantially out of the limelight and out of the history books.

Burn was a particularly influential figure in Manchester Liberal politics. His obituary remembered him as “one of the most successful, as he was one of the most agreeable, personalities among the professional party workers in the North of England.” If anything, it is possible that his obituary understated Burn’s influence. “Mr. Burn’s experience of political activity included the organization of the Liberal campaign against Mr. Winston Churchill when he was Conservative candidate at Oldham.”[1] Churchill lost the July 1899 Oldham by-election – his first attempt at Parliament. Half a decade later, Churchill turned for help to the very same, shrewd Liberal party fixer who had thwarted him.

Burn was a particularly influential figure in Manchester Liberal politics. His obituary remembered him as “one of the most successful, as he was one of the most agreeable, personalities among the professional party workers in the North of England.” If anything, it is possible that his obituary understated Burn’s influence. “Mr. Burn’s experience of political activity included the organization of the Liberal campaign against Mr. Winston Churchill when he was Conservative candidate at Oldham.”[1] Churchill lost the July 1899 Oldham by-election – his first attempt at Parliament. Half a decade later, Churchill turned for help to the very same, shrewd Liberal party fixer who had thwarted him.

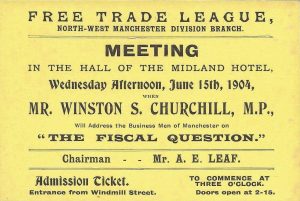

In 1903, The Manchester Liberal Federation (M.L.F.) “wanted ‘a superior man’”.[2] Burn was named Secretary of the Manchester Liberal Federation (MLF) and immediately “under him the staff was re-organised.” His £500 salary was “at the top end of the scale”, reflecting both his efficacy and the importance of his constituency.[3] Burn would more than earn his salary. A 24 March 1904 publication of the MLF lamented the death of the Liberal candidate for North-West Manchester and noted that “it is hoped that in the immediate future another name be put before the North-West Division.

In 1903, The Manchester Liberal Federation (M.L.F.) “wanted ‘a superior man’”.[2] Burn was named Secretary of the Manchester Liberal Federation (MLF) and immediately “under him the staff was re-organised.” His £500 salary was “at the top end of the scale”, reflecting both his efficacy and the importance of his constituency.[3] Burn would more than earn his salary. A 24 March 1904 publication of the MLF lamented the death of the Liberal candidate for North-West Manchester and noted that “it is hoped that in the immediate future another name be put before the North-West Division.

That name was one familiar to Burn – Winston Churchill.

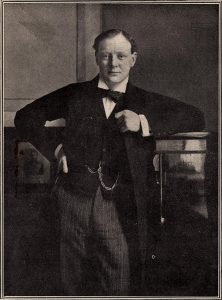

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal.

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal.

Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.”[4]

Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.”[4]

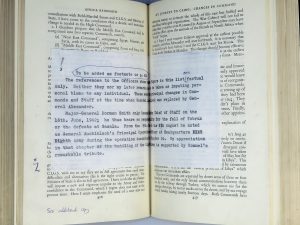

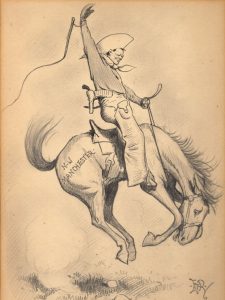

Burn helped balance the electoral scales in Churchill’s favor, guiding both local party organization and Churchill himself. The Churchill Archives Centre houses dozens of letters from Burn to Churchill, spanning the weeks before Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party to the death of Churchill’s mother in 1921. During Churchill’s initial transition to the Liberal Party, Burn was a constant source of information and guidance, some of which was minutely prescriptive. Burn’s counsel was not unsolicited, but rather deliberately sought. Many of Burn’s letters are responses to direct inquiries from Churchill. In a three-page, 15 July 1904 letter, Burn explained the constitution and organization of the Manchester Liberal Federation and how it functioned in relation to Liberal Party politics, including Party organization, political propaganda, and finance. Burn advised Churchill in all three categories in granular detail.

A number of Burn’s letters to Churchill consist of detailed schedules for Churchill – whom he should meet, where he will speak, and even what he will speak about. In a 17 March 1905 letter, Burn wrote to Churchill: “I have seen Mr Smith, the organizer of the Heyrod Street Hall Concert, and he has named 7.30 as the hour of meeting, half an hour earlier than is customary. He hopes that you will speak for about twenty minutes and that you will say something about your experiences in South Africa as he wants the audience to carry away something that they will remember and which will stick by them. A personal reminiscence of this character connected with your exploits there he thinks is just the thing… Mr Smith is anxious that not the slightest allusion, directly or indirectly, to anything political shall be made at Heyrod Street, Party politics are tabooed there, although outside he will be an active worker in your behalf.” Burn was careful to direct Churchill to the Jewish community that made up a large portion of North-West Manchester population, setting up meetings with Rabbis and visits to Jewish clubs. Burn also advised Churchill on the organizations with which he should associate. On 31 October 1904, Burn wrote “with reference to your inquiries – I have spoken to one or two of our people privately about this and their opinion is that it might be useful to you in your campaign to be associated with a body so influential as the Oddfellows.”

“Political propaganda” was a major function of Burn’s MLF, with a reported half a million political leaflets and cartoons delivered to Manchester houses in 1903. A 23 January 1905 letter from Burn to Churchill reveals the complex calculations Burn and the MLF made in the design of materials. “The Free Trade League people are a bit afraid that if we announce you by poster for St John’s Meeting, it will detract from theirs in the Free Trade Hall, which is quite close… what I suggest is that we should put out an ordinary poster but without your name, and that we should notify by circular our St John’s friends that you will be present.”

Money being integral to political calculus, the subject comprised a significant portion of Burn’s writing to Churchill. Burn’s recommendations of organizations that should receive a subscription under Churchill’s name were remarkably detailed. The Welsh Women’s Temperance Association were made of “splendid workers in every good cause, including liberalism”. Thus Churchill was to give them a small subscription (letter of 14 April 1905). The Royal Army Medical Corps of Manchester should get two guineas (letter of 8 May 1906) while Burn remarked about the Hightown A.F.C. “you can let this application ‘slide’, it is a very small affair” (8 August 1906). One charmingly detailed letter of 12 April 1906 to Churchill’s secretary reads “I have your letter regarding the appeal from the Manchester Grammar School. I think it would be well for Mr Churchill to give a small subscription as there are about a thousand boys in the school representing a great number of families in the Division. Besides that, the boys are very keen on politics at the present moment and have had mock Elections in which, by the way, one precocious youth posed as the Member for North-West Manchester [Churchill]. I notice they suggest a guinea as a first prize that I think should be sufficient.”

Burn’s correspondence with Churchill makes apparent the importance of the individual voter in these community elections, which were often decided by hundreds of votes. Much of Burn’s counsel was truly inside information – which community members to meet, clubs to visit, churches and dinners and teas and garden parties to attend. A 14 April 1905 letter to Churchill’s secretary provided characteristically informed and specific advice: “I hope Mr Churchill will pardon me mentioning that a letter from him expressing his regret at hearing of Mr Eward’s illness would be appreciated.”

Burn was a lynchpin to Churchill’s success. And Churchill’s success was critical to the Liberals. On 13 January 1906 Churchill won the traditionally Conservative seat by a majority of 1,241 in an electorate of 10,000. His fellow Liberal campaigners became beneficiaries. “His efforts in and around Manchester helped six other Liberal candidates to overturn Conservative seats.” His cousin Ivor Guest wrote to him: “You have given the pendulum such a swing as will be felt throughout the whole country.”[5] The Liberals won 377 seats in an electoral landslide.

North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate.

North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate.

Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”.[6] Two years later, in 1908, Churchill would marry and be appointed to his first Cabinet post. As a powerful Liberal Cabinet Minister during the First World War, Churchill would experience a cycle of political ruin and rehabilitation echoing – and preparing him for – the ostracism of the 1930s that preceded his vindicated role as Prime Minister during the Second World War. Churchill would ultimately hold six different Cabinet posts under two Liberal prime ministers and would remain a Liberal until 1924, following the electoral destruction of the Liberal Party.

Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”.[6] Two years later, in 1908, Churchill would marry and be appointed to his first Cabinet post. As a powerful Liberal Cabinet Minister during the First World War, Churchill would experience a cycle of political ruin and rehabilitation echoing – and preparing him for – the ostracism of the 1930s that preceded his vindicated role as Prime Minister during the Second World War. Churchill would ultimately hold six different Cabinet posts under two Liberal prime ministers and would remain a Liberal until 1924, following the electoral destruction of the Liberal Party.

All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.

All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.

This item – and dozens of other signed, inscribed, or handwritten treasures – will appear in our “Extra Ink” catalogue to be printed at the end of this year. Special thanks to our resourceful and indefatigable Churchill Book Collector colleague Elise, for much of the research for this post.

[1]The Berwick Advertiser, 14 August 1930

[2]Peter Clarke, Lancashire and the New Liberalism, p.207

[3]Kathryn Rix, “Hidden Workers of the Party”, Journal of Liberal History, 52 (2006), p.12