We’ve just been reminded of a remarkable moment of holiday season humanity in the midst of the First World War that seems appropriate to share during these more than normally fraught 2020 holidays.

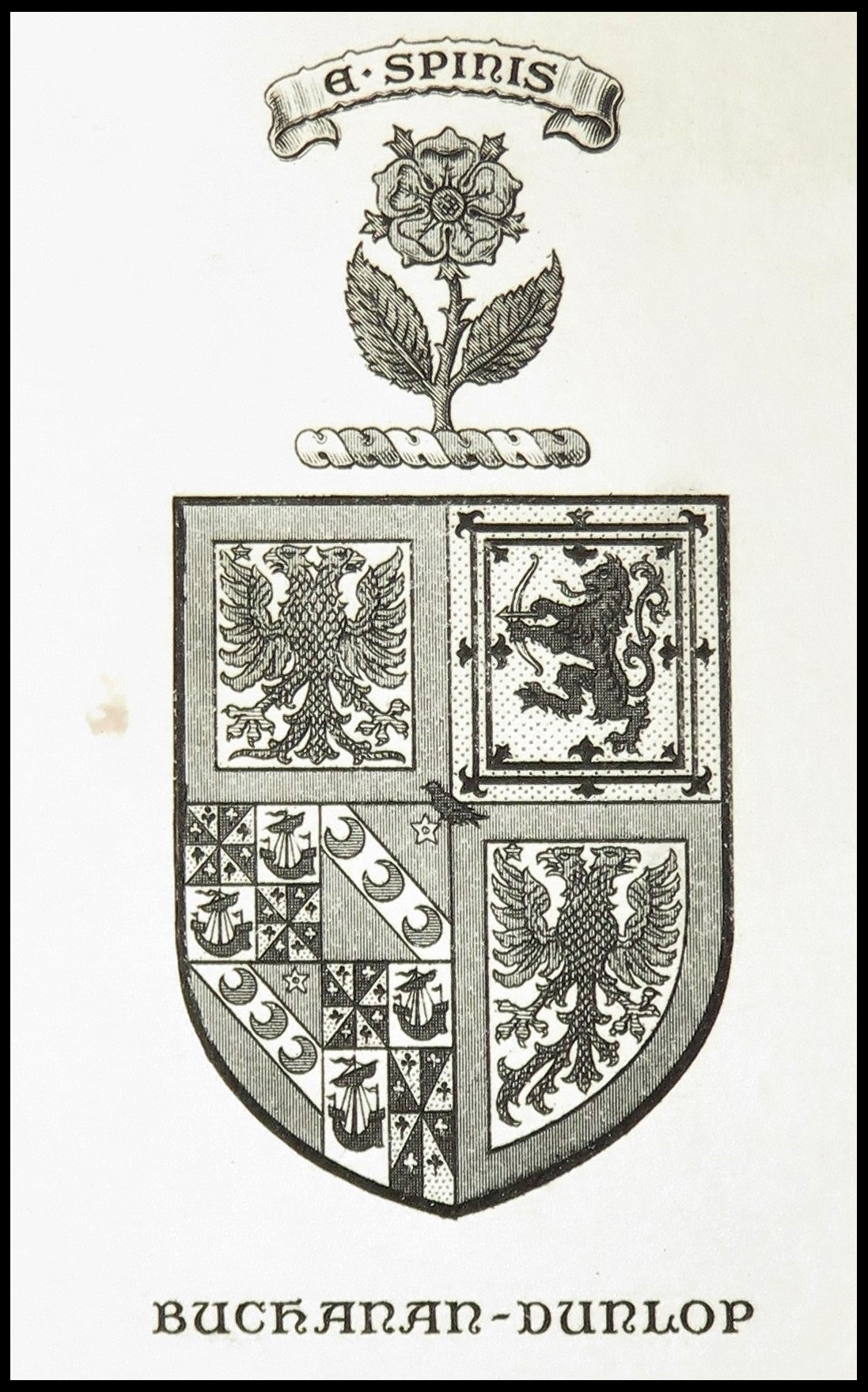

It begins with a bookplate

The catalyst is a set of the signed, limited, numbered, and finely bound first edition of Winston Churchill’s four-volume biography of his great ancestor, John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough – one of England’s most celebrated military leaders. Marlborough: His Life and Times is noteworthy for being Winston Churchill’s final monumental interregnum work. Churchill had served both in the Cabinet and on the Front during the First World War. Almost exactly one year after publication of the fourth and last Marlborough volume, Churchill returned to the Cabinet at the outbreak of the Second World War.

The publisher’s 150 signed, limited, numbered and finely bound sets of Marlborough are coveted, so it’s easy to dismiss the presence of old bookplates in each volume as merely a “previous owner’s bookplate”. But the bookplate in each volume of set #107 happens to be the armorial bookplate of “BUCHANAN-DUNLOP”.

You’ve probably not heard the name, but it is one that merits attention, particularly at this time of year. On Christmas day, 1914, Lt Col. Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop (1874-1947) did what even the Pope could not.

“There is no limit to the measure of ruin and of slaughter”

The First World War was only a month old when Benedict XV ascended to the papacy. The first four of his seven and a half years as Pope were consumed by diplomatic attempts to quash the conflict he described as “the suicide of civilized Europe”. But secular exhortations proved no match for the terrible pent political and military forces that had been unleashed. That November Benedict XV said of the combatants in his Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum encyclical “…well provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised they strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror. There is no limit to the measure of ruin and of slaughter; day by day the earth is drenched with newly-shed blood, and is covered with the bodies of the wounded and of the slain.”

The Pope pressed his impassioned appeal for peace; on 7 December he called for a hiatus from war to last at least over the holiday, so that “the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.” His request for an official cease-fire was universally ignored. Almost. A truce came not on the scale of secular institutions, nation states, and official decrees, but instead through a modest package, delivered to a British officer on the edge of the cold, muddy morass of No-Man’s Land in Ypres.

“…it seems so silly under the circumstances to be fighting them.”

The recipient was Lt Col. Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop. He had written to his mother about how he missed the songs the students would sing at the Chapel of Loretto School, where he had been a student and a teacher. The package from his mother contained a small program, a book of carols for the school’s annual Christmas production. On Christmas day, Buchanan-Dunlop organized an impromptu song among his company, which quickly erupted with more and more soldiers joining down the trenches. The Germans responded in kind, each side cheering after the other. Soldiers climbed out of their trenches and shook hands with their enemies. Some exchanged gifts of cigarettes and plum puddings. There was even a documented case of soldiers from opposing sides playing a good-natured game of soccer.

In retrospect, historical accounts tend to garland a single individual as the sole instigator of an event. In this way, of course it might be over-zealous to ascribe the 1914 Christmas Truce wholly to Lt. Col. Buchanan-Dunlop, but only marginally so. In a letter he sent to his wife on Christmas day 1914, Buchanan-Dunlop wrote, “Even out here this is a time of peace & goodwill. I have just spent an hour talking to the German officers & men who have drawn a line half way between our left trenches & theirs & have all met our men and officers there. We exchanged cigars, cigarettes, and papers. They are jolly, cheery fellows for the most part, & it seems so silly under the circumstances to be fighting them.” It’s clear from the remainder of the letter that Buchanan-Dunlop did not take credit for the truce—a testament to his character—but letters sent from fellow soldiers name him as the cause.

2014 marked the centennial anniversary of the fabled events and a remembrance for the man who was said to have – even if only for a moment – “stopped the First World War”. Stained-glass windows were commissioned in commemoration of the truce, which have been installed in Loretto School’s Chapel. Descendants of Buchanan-Dunlop, as well as those of the German officer involved in the truce, Hauptmann Maximilion Freiherr Von Sinner, congregated as their forebearers did, during the unveiling of the windows, which in Latin read, Gloria in Excelsis Deo et in terra pax, meaning, Glory to God in the Highest, and on earth peace.

The return to exchanging fire

Many of the men who sang and shook hands on Christmas 1914 did not survive; they returned to exchanging fire. It went on for nearly four more desperately bloody and destructive years. Then it all began anew in 1939. The First World War had been called “The Great War” and even “The War to End All Wars”. Only four decades into the twentieth century the world was already jaded; the next global conflict became merely the “Second” World War. And in that sequel, three of Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop’s own sons took up arms and served.

It occurred to me as I was writing this post to search out an inventory of current global conflicts – incidences of organized, sustained, mass violence fueled by large-scale sectarian or political strife. This proved such a lengthy and dismal catalogue that I stopped.

Even the lovely, erudite, eminently worthy books in which we found the Buchanan-Dunlop bookplates suggest terrible inevitability. Winston Churchill’s history of his great ancestor – a vaunted military commander of the early 18th century – was written while Churchill himself was desperately seeking to forestall the next great engulfing conflagration of his own time. Churchill failed. Instead, it fell to him to lead his nation in war.

One can become understandably pessimistic. But there is more to it than that. Were there not, I’d be unable to write these words today.

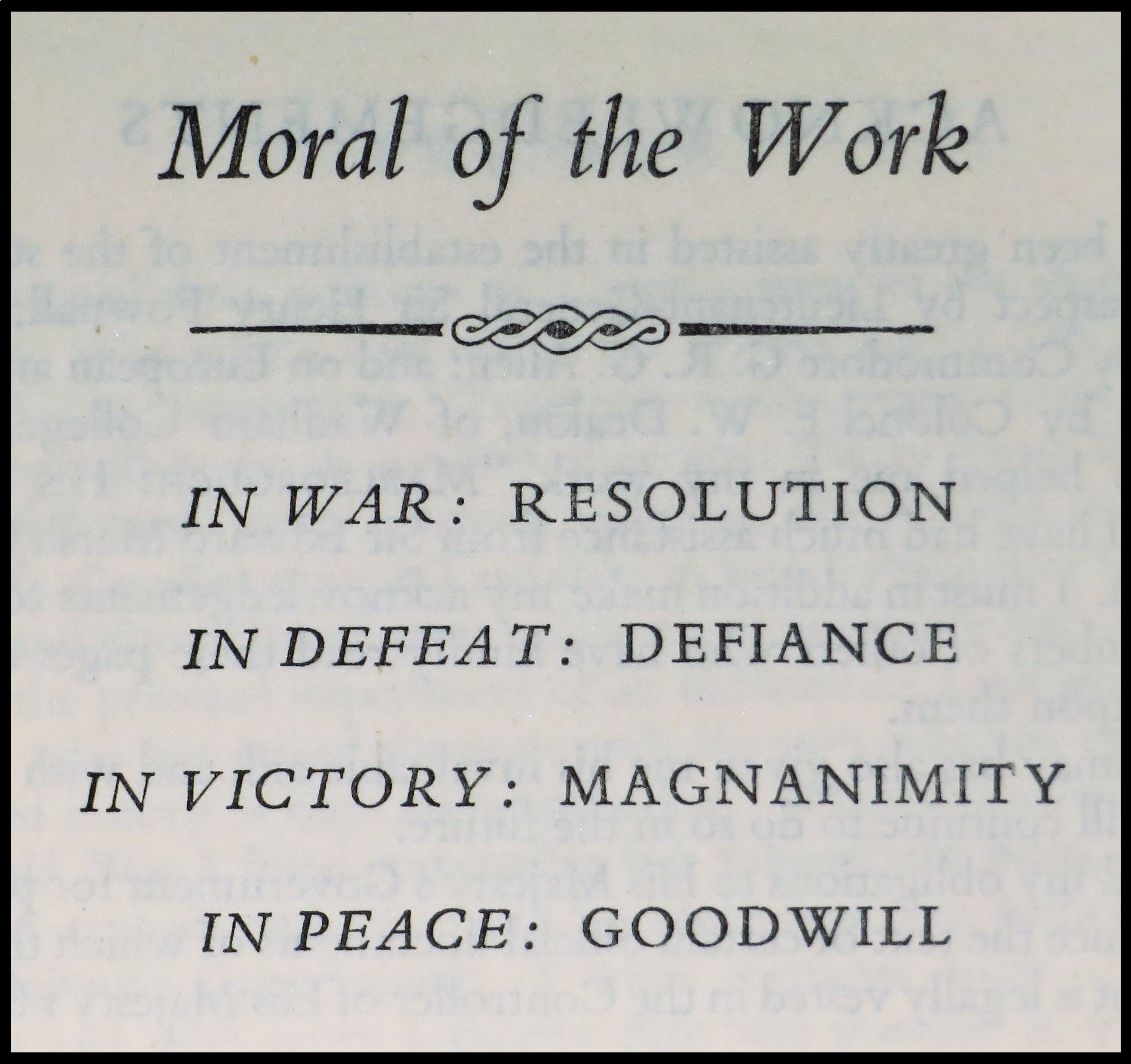

The “Moral of the work”

In the trenches of Ypres on Christmas 1914, Archibald Henry Buchanan-Dunlop sensed that there was more and helped his fellow soldiers, allied and enemy both, to momentarily do the same. We regard the Christmas Truce moment – we enshrine it in stained glass 100 years later – because we understand that even the depths of senseless depravity may harbor the fragile, stubborn, never-quite-fully-extinguished possibility of beneficent humanity.

After the First World War, Winston Churchill was asked to pen an inscription for a French First World War memorial. In response, Churchill offered the following:

In War: Resolution

In Defeat: Defiance

In Victory: Magnanimity

In Peace: Good Will

Churchill’s proposed inscription was rejected. France – and most of the leadership and populace among most of her allies – were in too vengeful a mood to enshrine any notions of magnanimity or good will. Indeed, the venomously punitive terms imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles are widely credited (including by Churchill) with helping aid the rise of Hitler.

Like the resumption of hostilities after the Christmas Truce, the rejection of Churchill’s proposed inscription is a tremendously fitting commentary on the persistent failure to learn – to secure peace not just with frightful loss of blood and treasure, but with comprehending and conciliatory spirit. Prophetically, Churchill’s rejected inscription for a First World War memorial instead became his “Moral of the Work” when he published his history of The Second World War.

Wishing us all the resolution and defiance necessary to show magnanimity, achieve peace, and proffer good will.

This item may be purchased HERE.

Cheers!