For those of you unfamiliar with polemic German, that translates “Churchill the World Liar.” This subtle and gently nuanced critique, below an unflattering original caricature of Winston S. Churchill appears to have been inked by a German soldier on 3 October, just a month after the Second World War began. This ostensibly unique, hand-drawn poster survived nearly five years of war before it was recovered from captured German barracks by an Allied solder.

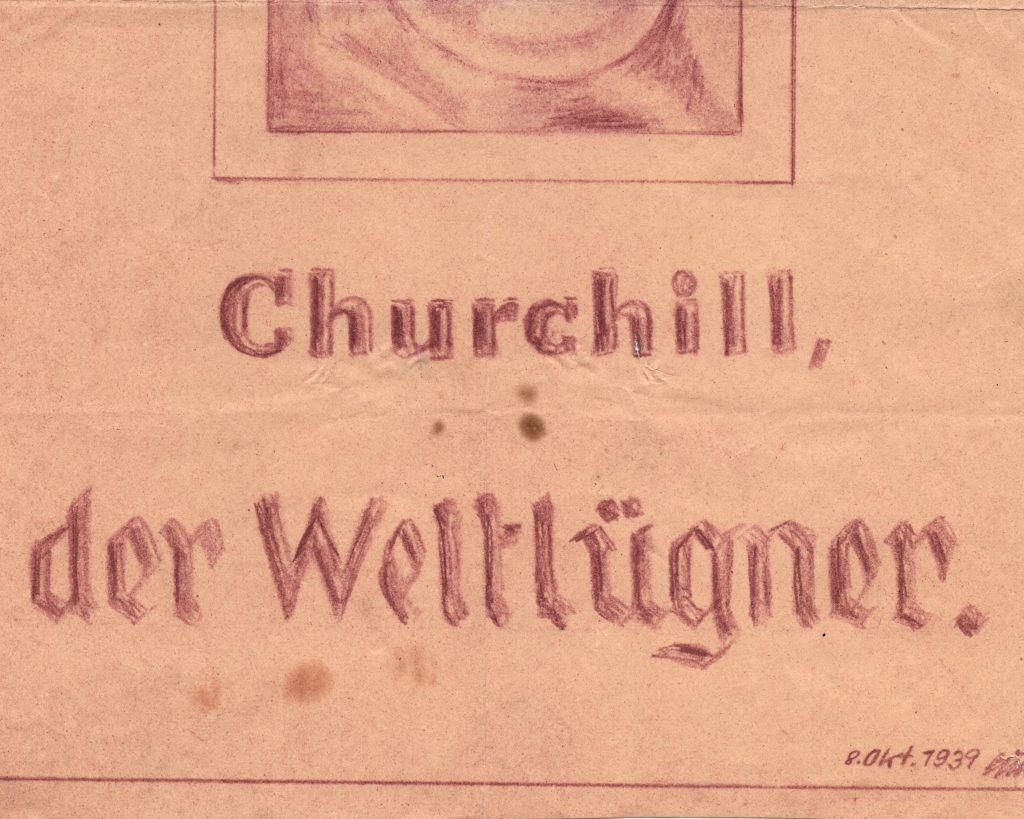

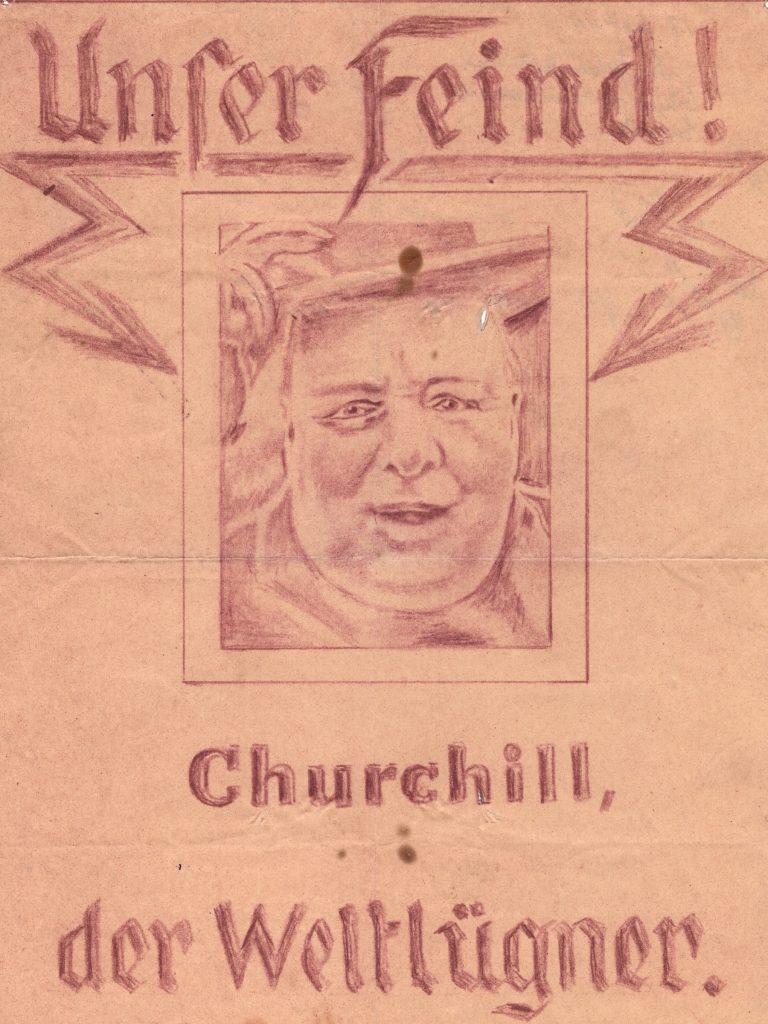

The piece measures 12.25 x 8.5 inches (31.1 x 21.6 cm). The drawing features a slightly demonically-rendered countenance of Winston S. Churchill wearing a hat high on his head, cocked to the right with a stylized, gloved hand clawing around the brim. Churchill’s eyes are slightly asymmetrical and horizontally elongated, the roundness of his face slightly and unflatteringly exaggerated, his mouth open. The net effect is oddly evocative of an inebriated, rotund, clumsily malign and yet simultaneously ridiculous German burgher. The drawing, measuring 4.5 x 3.5 inches (11.4 x 8.9 cm) and framed by two border rules, occupies the upper center of the paper below a prominent, underscored title labeling the image “Unser Feind!” (“Our Enemy!”). Lightning-shaped arrows originating from the underscoring beneath the title point unsubtly to either side of the image – just in case the identity of the subject “Unser Feind” is in question. Centered directly below Churchill’s image are two further lines: “Churchill, | der Weltlugner”. (“Churchill, the World Liar”). At the lower right corner, just inside of a single border rule, the image is dated “8 Okt. 1939” and signed by the artist. The signature is indecipherable.

Condition is very good, particularly given the age and wartime experience of the piece. There are pin holes at the corners, a small hole in the second “h” of Churchill’s name, and a small vertical hole, wider at the center and pointed at the ends, in Churchill’s upper right forehead; it requires little imagination to perceive the shape of this hole as consonant with a knife point. There are five small circular stains adjacent to the upper and lower vertical center, some light spotting to the blank lower portion of the drawing, light overall soiling, the soiling heavier to the upper verso, where we also note a small paperclip rust stain.

Clues to provenance are tantalizing. 3 October, when this piece was drawn and signed, was an optimistic day for the Wehrmacht; on this day in 1939, French forces completed their withdrawal from advanced positions in German territory and the last significant units of the Polish army surrendered, allowing German forces to begin redeploying from Poland to western Europe. Two days prior, on 1 October, Churchill, then still First Lord of the Admiralty, made his first wartime radio broadcast.

Of course Churchill was not yet wartime Prime Minister and the stern rhetoric that characterized his wartime speeches was perhaps somewhat tempered. Even so, any German solder listening would have rightly regarded Churchill as “Our Enemy!” Even as Britain’s allies were falling with shocking speed, Churchill spoke of resistance, resolve, and implacable opposition to Germany’s ascendant Fuhrer. Churchill told the British people to “…prepare for a war of at least years. That does not mean that victory may not be gained in a short time. How soon it will be gained depends upon how long Herr Hitler and his group of wicked men, whose hands are stained with blood and soiled with corruption, can keep their grip upon the docile unhappy German people. It was for Hitler to say when the war would begin, but it is not for him or his successor to say when it will end. It began when he wanted it, and it will end only when we are convinced that he has had enough.”

We do not know what befell the artist who created this poster, or the soldiers who had it in their barracks four years, eleven months, and fifteen days after it was signed and dated. Nonetheless, we can be sure that the world and the war looked much different to Germany and her soldiers than it had on 3 October 1939.

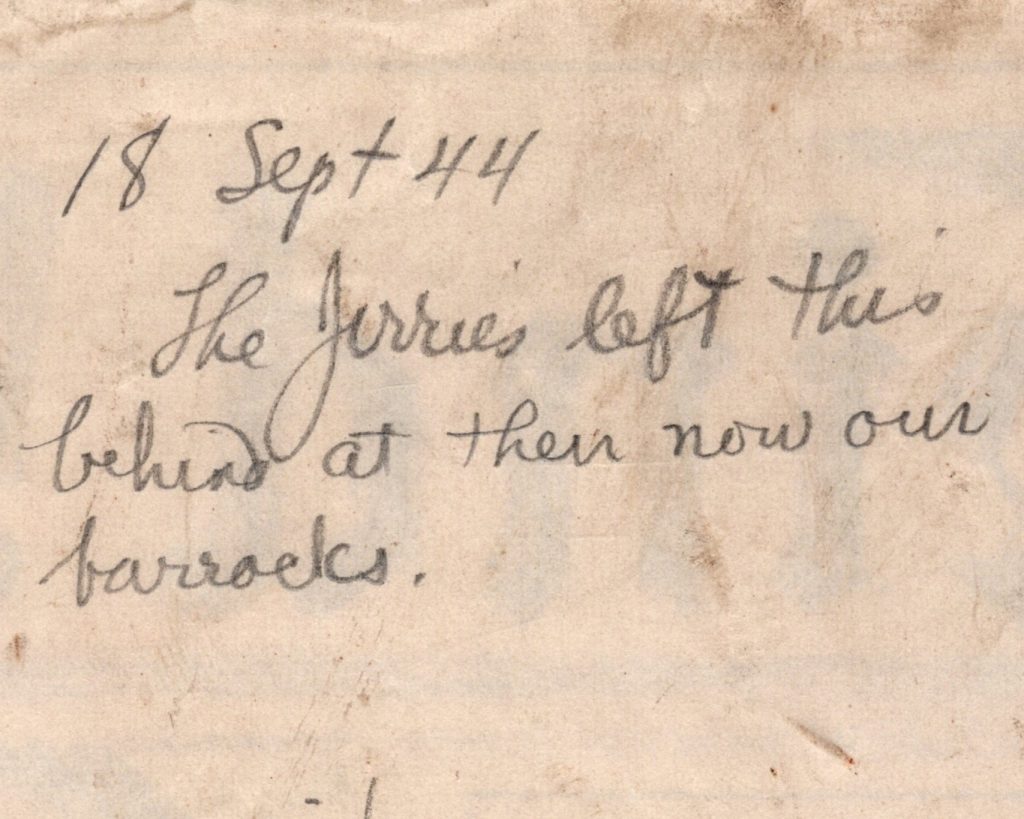

At the upper left of the poster’s verso is a dated notation in pencil in four lines: “18 Sept 44 | The Jerries left this | behind at their now our | barracks.” Below and in a different hand, also in pencil, is a translation of the poster “Our enemy | the world liar”. Pin holes at the center of circular thumbtack indentations at each corner make it seem more than probable that this poster was displayed informally. Perhaps that is how it was discovered by the presumed allied soldier who made the notation on the back of the poster. The term “Jerry” to refer to the Germans was used generally by Allied soldiers and civilians, but originated with, and was most used by, the British. We cannot be sure of exactly where or by whom this poster was found, but in the European theater in mid-September 1944, Operation ‘Market Garden’ – involving one of the largest airborne operations in history – was underway. On Monday, 18 September 1944, British ground troops linked with U.S. 101st Airborne Division in Eindhoven, Holland.

The juxtaposition of the sentiments with which this unique artifact was drawn at the beginning of the war, and the manner in which it was discovered and claimed almost five years later, limn the brutal arc from the heady initial blitzkrieg of German ascendance to imminent, ignominious, and utter defeat.

This piece was once part of the extraordinary collection of Philip David Sang (1902-1975). Sang donated manuscript collections to Brandeis University, Yale University, the Illinois State Historical Museum and to Southern Illinois University, among others. He also loaned items from his vast collection to many museums and libraries for historical exhibits. Following his death, his widow, Elsie Olin Sang, sold many of his remaining manuscript and archival collections. This piece thus made its way to a colleague in the book trade, who held it for a number of years before conveying it to us.

As for the subject of this caricature, the artist hardly needed to go to the trouble of identifying his subject as “Churchill”. Prolific and almost instantly recognizable caricature would characterize most of Winston Churchill’s long life. Years before this particular caricature was drawn, Churchill said “cartoons are the regular food on which the grown-up children of to-day are fed and nourished. On these very often they form their views of public men and public affairs; on these very often they vote… But how… would you like to be cartooned yourself? How would you like to feel that millions of people saw you always in the most ridiculous situations, or portrayed as every kind of wretched animal, or with a nose on your face like a wart, when really your nose is quite a serviceable and presentable member? How would you like to feel that millions of people think of you like that? – that shocking object, that contemptible being, that wretched tatterdemalion, a proper target of public hatred and derision! Fancy having that process going on every week, often every day, over the whole of your life… But it is not so bad as you would expect. Just as eels are supposed to get used to skinning, so politicians get used to being caricatured. In fact, by a strange trait in human nature they even get to like it. If we must confess it, they are quite offended and downcast when the cartoons stop…” (Thoughts and Adventures, 1932) So recognizable did Churchill become that for his final political campaign in 1959 his poster was a simple, solid blue profile of his instantly recognizable countenance, with the inevitable cigar protruding – the alleged Weltlugner become instead a Weltfuhrer.

Cheers!