This time of year always makes my southern California home feel furthest from my Northeast roots. It is always Robert Frost who brings me to my source.

This season, I have the good fortune to have an evolving draft of a poem written in Frost’s own hand to tell you about – and what’s more, it is a poem appropriate to the spirit of the season. But first, a bit more about Frost for the benefit of those of you unfamiliar.

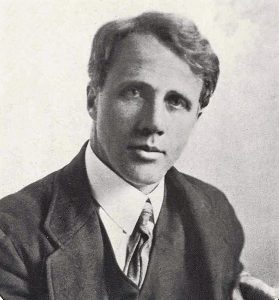

Great literature is full of contradictions. So it is that the quintessential poetic voice of New England was actually born in San Francisco and first published in England. Iconic American poet Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) would ultimately win the Pulitzer Prize four times and spend the final decades of his life as “the most highly esteemed American poet of the twentieth century” – but he did not publish his first volume of poetry until he was nearly forty years old. It was titled A Boy’s Will – another irony for a father by then approaching middle age.

Great literature is full of contradictions. So it is that the quintessential poetic voice of New England was actually born in San Francisco and first published in England. Iconic American poet Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) would ultimately win the Pulitzer Prize four times and spend the final decades of his life as “the most highly esteemed American poet of the twentieth century” – but he did not publish his first volume of poetry until he was nearly forty years old. It was titled A Boy’s Will – another irony for a father by then approaching middle age.

When Frost was eleven, his newly widowed mother moved east to Salem, New Hampshire, to resume a teaching career. There Frost swiftly found his poetic voice, infused by New England scenes and sensibilities. Promising as a student and writer, Frost nonetheless dropped out of both Dartmouth and Harvard, supporting himself and a young family by teaching and farming.

It was a 1912 move to England with his wife and children – “the place to be poor and to write poems” – that finally catalyzed his recognition as a noteworthy American poet. The manuscript of A Boy’s Will was completed in England and accepted for publication by David Nutt on 1 April 1913. Yeats pronounced the poetry “the best written in America for some time” and Frost received “two extraordinary tributes in the Nation and the Chicago Dial and a superb review in the Academy.” (ANB) A convocation of critical recognition, introduction to other writers, and creative energy supported the English publication of Frost’s second book, North of Boston, in 1914, after which “Frost’s reputation as a leading poet had been firmly established in England, and Henry Holt of New York had agreed to publish his books in America.”

Accolades met his return to America at the end of 1914 and by 1917 a move to Amherst “launched him on the twofold career he would lead for the rest of his life: teaching whatever “subjects” he pleased at a congenial college… and “barding around,” his term for “saying” poems in a conversational performance.” (ANB) By 1924 he had won the first of his eventual four Pulitzer Prizes for poetry (1931, 1937, and 1943). Fame and a host of academic and civic honors accreted during Frost’s final decades. Two years before his death he became the first poet to read in the program of a U.S. Presidential inauguration (Kennedy, January 1961).

Accolades met his return to America at the end of 1914 and by 1917 a move to Amherst “launched him on the twofold career he would lead for the rest of his life: teaching whatever “subjects” he pleased at a congenial college… and “barding around,” his term for “saying” poems in a conversational performance.” (ANB) By 1924 he had won the first of his eventual four Pulitzer Prizes for poetry (1931, 1937, and 1943). Fame and a host of academic and civic honors accreted during Frost’s final decades. Two years before his death he became the first poet to read in the program of a U.S. Presidential inauguration (Kennedy, January 1961).

All of which is by way of introducing a poem.

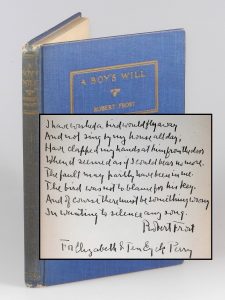

It was not uncommon for Frost to inscribe his books with excerpts from his poems. But we recently acquired a particularly special copy – an American first edition of the author’s first published book inscribed by Frost on the front free endpaper in 10 lines with the full text of the evolving draft of an untitled poem that would be published in 1928’s West-Running Brook as “A Minor Bird”.

It was not uncommon for Frost to inscribe his books with excerpts from his poems. But we recently acquired a particularly special copy – an American first edition of the author’s first published book inscribed by Frost on the front free endpaper in 10 lines with the full text of the evolving draft of an untitled poem that would be published in 1928’s West-Running Brook as “A Minor Bird”.

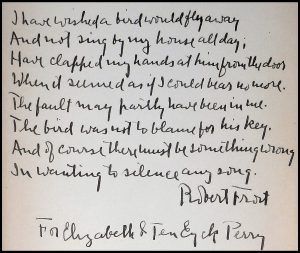

The full inscription reads: “I have wished a bird would fly away | And not sing by my house all day, | Have clapped my hands at him from the door | When it seemed as if I could bear no more. | The fault may partly have been in me. | The bird was not to blame for his key. | And of course there must be something wrong | In wanting to silence any song. | Robert Frost | For Elizabeth & Ten Eyck Perry”.

Significantly, this untitled manuscript version of “A Minor Bird” is an evolving draft, following the poem’s first publication in Inlander magazine (of the University of Michigan) in 1926, but preceding the first volume publication in 1928. When published in Inlander, the poem read “may” instead of “must” at line 5, “I own” instead of “of course” in line 7, and in the final, 8th line “ever wanting to silence song” instead of “wanting to silence any song.” This manuscript copy reflects the changes to lines 7 & 8, but does not yet incorporate the change to line 5. The difference between “must” and “may” is substantive, at both the physical and literary center of the poem.

Consonant with the evolving draft, this copy was likely inscribed in November 1927, placing it squarely between the original, 1926 publication in Inlander and publication in West-Running Brook (19 November 1928). We were able to confirm that Henry Ten Eyck Perry (1890-1973), a native of Albany, New York, was a writer and professor of English. Ten Eyck Perry graduated from Yale in 1912, received his doctorate from Harvard in 1918, published a number of books, and taught English at the University of Buffalo. There he apparently interacted with at least one other major American poet; T.S. Eliot wrote in a letter of 26 December 1932 that he was to visit “Buffallo or is it Buffalo Bufallo Bufaloo to stay with Professor Henry Ten Eyck Perry.” The marriage of Elizabeth Ten Eyck Perry (nee Elizabeth McAfee, 1888-1976) led to her involvement with the University of Buffalo, where she was the founding president of the Women’s Club in 1946. In the University of Buffalo’s archives we find reference to two visits from Robert Frost, once to deliver a lecture in 1921 and for a three day stay in 1927. This inscription was likely made in November of 1927, when Frost visited the University of Buffalo as “poet in residence”. The school’s newspaper notes that during his three day visit he had office hours and “his time [was] at the service of students, faculty, and to a certain extent of townspeople.”

It was a particular pleasure to research this particular poem at this particular time of year. The “Minor Bird” is eponymous (and synonymous) with the myna (or mynah) bird, which can mimic human speech. “Song” is a repeated metaphor used by Frost for creative, free expression. Hence, we can infer the author criticizing the impulse to stifle creative expression – a churlish impulse as endemically human as is the urge to creative expression itself. Particularly lovely is that the author chooses to recognize and criticize the impulse in himself. And that this evolving draft shows him making that self-admonition more definitive with the changes that had already been made, as well as the final change – “may” to “must” in line 5 – that had yet to be made when Frost penned this inscription in 1927.

To me, the poem is a conch shell of spiraling, widening, opening awareness.

The poet, in the midst of creative expression, acknowledging the dynamic tension between creation and judgement, his reflexive chastisement of competing voices yielding to acknowledgement and acceptance. The recognition of himself in “any song” which allows him to hear – and thus to give voice himself.

For the season, I found it even more bracing than “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and a gentle reminder that I, too, have “miles to go before I sleep” – in patience, in understanding, and, if I am fortunate, in hearing the chorus that enfolds and enriches my own voice.

Cheers!