“Lawrence of Arabia” has occupied a prominent place in popular imagination for a century. By this time, there should be little new to say about him. But, despite books, movies, and countless biographical examinations and portrayals, not to mention a staggering amount of press attention and speculation during and after his lifetime, Lawrence remains a remarkably enigmatic figure. Perhaps that’s why Lawrence’s correspondence continues to be so interesting. Correspondence – by its nature more ephemeral, candid, and more distinctly in and of the moment than published works – can convey a vital sense of the correspondent. Hence our post today about a letter we have just catalogued.

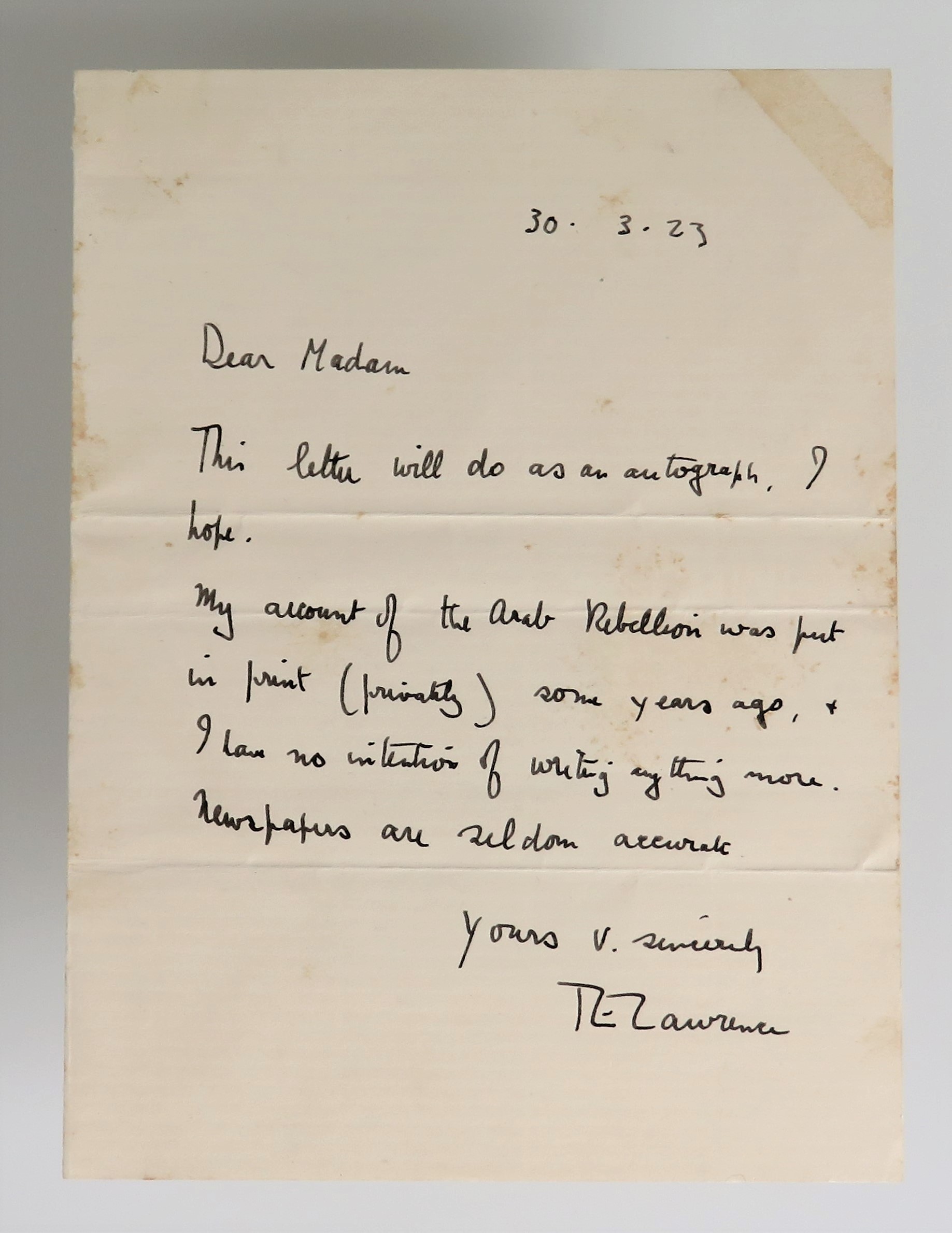

This is a 30 March 1923 autograph letter signed by T. E. Lawrence, noteworthy for testimony to his perpetually unresolved conflict over his magnum opus, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, evolving complications of his public persona and media stardom, and for being signed with the name he would soon abandon.

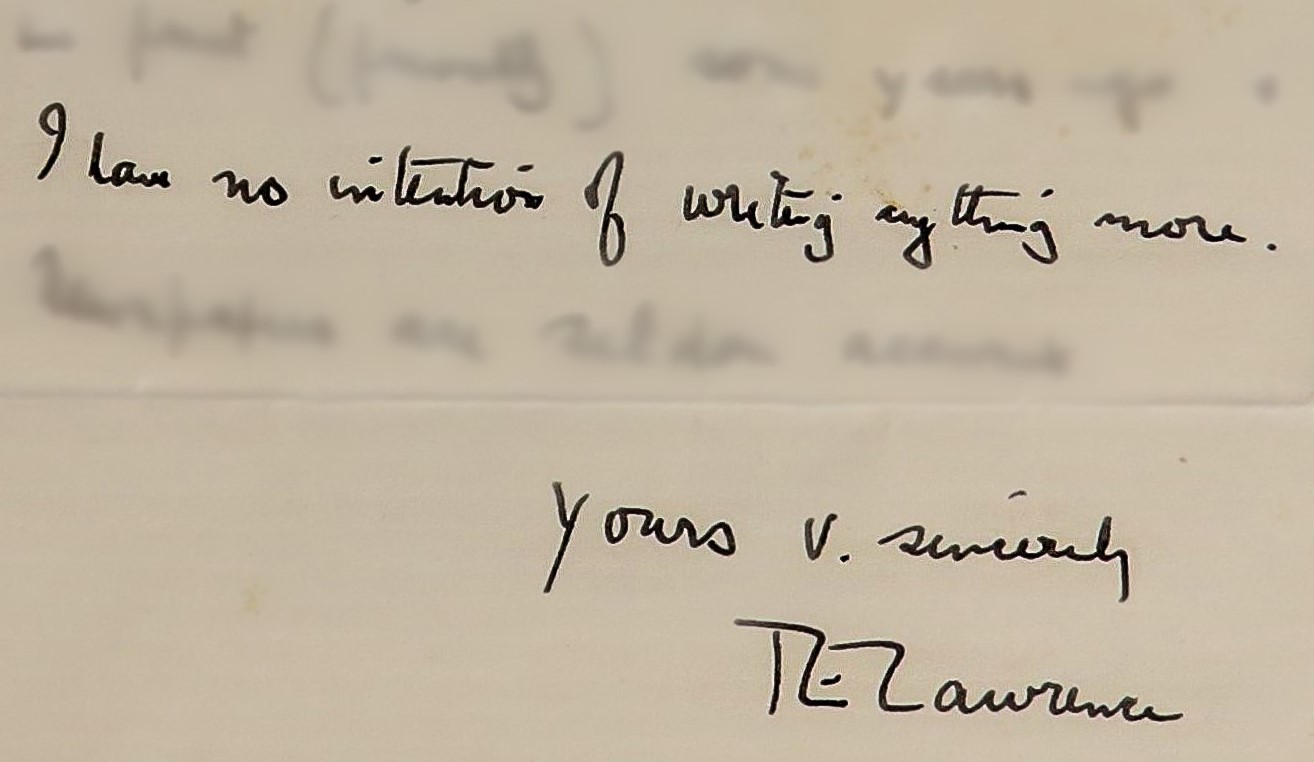

The letter is inked on the first panel of a single sheet of laid paper folded once to form two 6 x 4.44 inch (15.24 x 11.28 cm) panels. Lawrence’s letter, in 10 lines, reads: “30.3.23 | Dear Madam | This letter will do as an autograph. I | hope. | My account of the Arab Rebellion was first | in print (privately) some years ago, & | I have no intention of writing anything more. | Newspapers are seldom accurate | yours v. sincerely | T E Lawrence”. The letter to which this one replies and the recipient are unknown to us. But it seems quite likely that the unidentified “Madam” wrote to Lawrence as an admirer, both seeking an autograph and inquiring about the book he seemed always about to publish. Quite plausibly, elevated media preceding this letter is what prompted the recipient’s inquiry to Lawrence.

T. E. Lawrence’s (1888-1935) remarkable odyssey as instigator, organizer, hero, and tragic figure of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War transformed him from an eccentric junior intelligence officer into “Lawrence of Arabia.” He spent the rest of his famously short life struggling to variously reconcile, reject, share, and repress this indelible experience, ultimately recounted in Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

As indicated in this letter, Lawrence famously resisted publication for the general public during his lifetime. By 1923 he had already undergone a tortuous saga of writing and re-writing, including the loss of his original draft. In 1922, a 335,000 word version was carefully circulated to select friends and literary critics – the famous “Oxford Text” referenced in this letter – somewhat misleadingly – as “in print (privately)”. George Bernard Shaw called it “a masterpiece” and in December 1922 Shaw’s wife, Charlotte, told Lawrence “…it is one of the most amazing individual documents that has ever been written… Your book must be published as a whole.”

In early 1923, many pressures came to a head for Lawrence. Months prior to this letter, Lawrence had been preparing an abridgement for publication by Cape. “He had often said that the purpose of the abridgement was to escape from the Airforce.” But Lawrence then resolved to stay in the RAF. He wrote to his agent “I .. made up my mind .. not to publish anything whatever: neither abridgement nor serial, nor full story: at least this year: and probably not so long as I remain in the R.A.F.” Consonant with this decision, Lawrence abruptly withdrew from his agreement with Cape on 1 January 1923.

Of note, this withdrawal deprived Lawrence of a source of income unless he remained in the Royal Air Force or found some other form of employment. But two days after Lawrence jilted Cape, he was visited by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Trenchard, who warned Lawrence his presence in the newspapers was making his continued presence in the Air Force untenable. Lawrence again flirted with the idea of publication, this time about an unabridged, illustrated, limited subscription edition. But by the end of January, he had again abandoned publication. And he had been discharged from the RAF. (Wilson, p.701)

With the RAF closed to him, Lawrence enlisted in the Tank Corps. Concurrently, he seemed to close the proverbial book on publication; “Lawrence took the surviving manuscript of Seven Pillars to Oxford and presented it to the Bodleian Library”. On 12 March – 18 days before this letter was written – Lawrence arrived at Bovington Camp for his eighteen weeks’ Tank Corps basic training. (Wilson, p.711) Lawrence had enlisted in the Tank Corps as “T. E. Shaw” – a name he would later formally adopt, both signing his correspondence and publishing thus. Hence it is noteworthy that this letter is signed “Lawrence”.

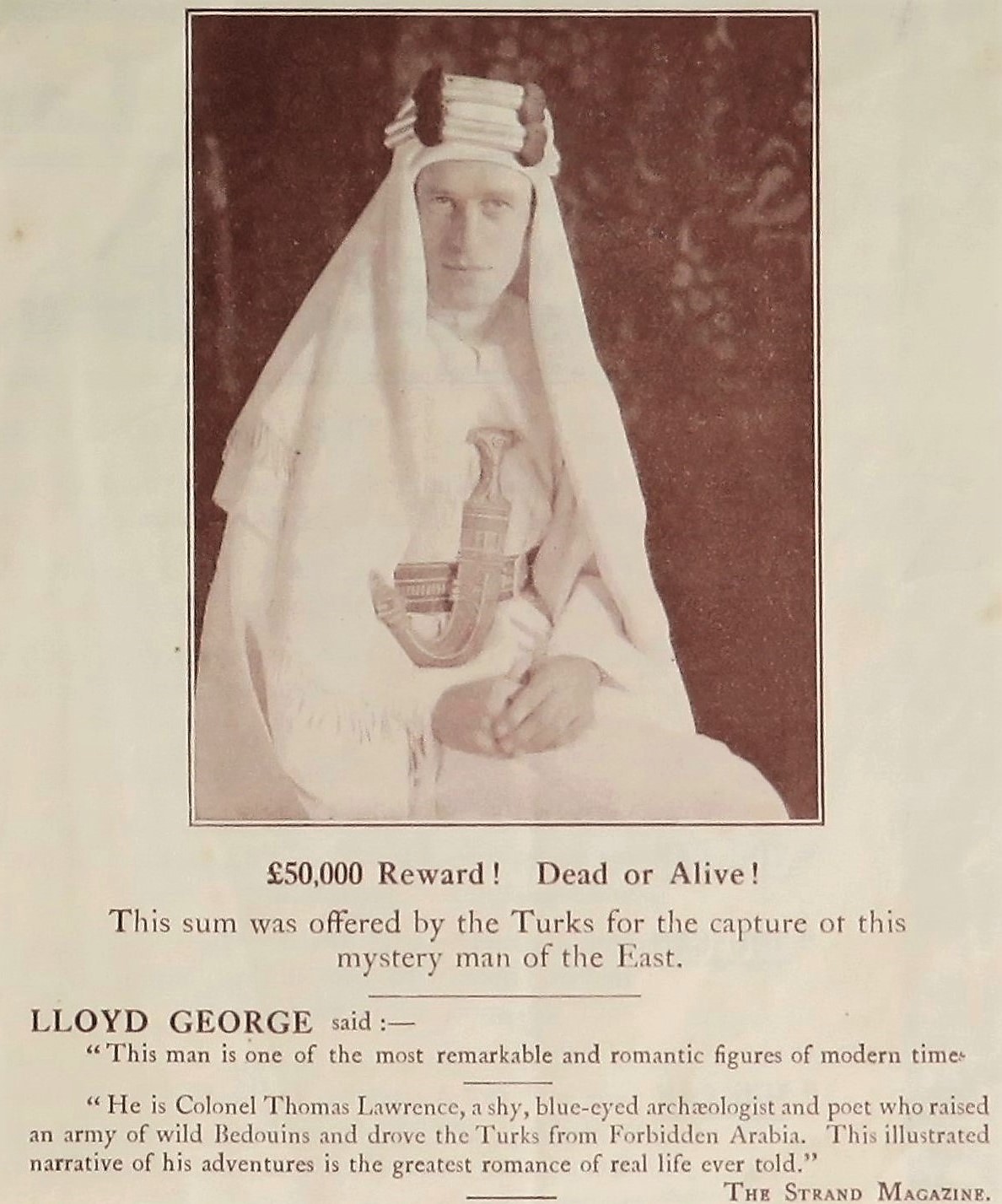

Lawrence’s comment “Newspapers are seldom accurate” is telling. Media attention had just cost Lawrence his preferred life in the Royal Air Force. “Hitherto, journalists had eaten out of his hand, and this had led him to the dangerous illusion that he could influence them as he pleased.” But “From now on he would be regarded by the world’s press as an enigmatic figure, whose motives and influence were open to endless speculation .. popular interest refocused inescapably on his own life ..” and “.. imposed very real restrictions on his personal freedom ..” (Wilson, pp.701-7)

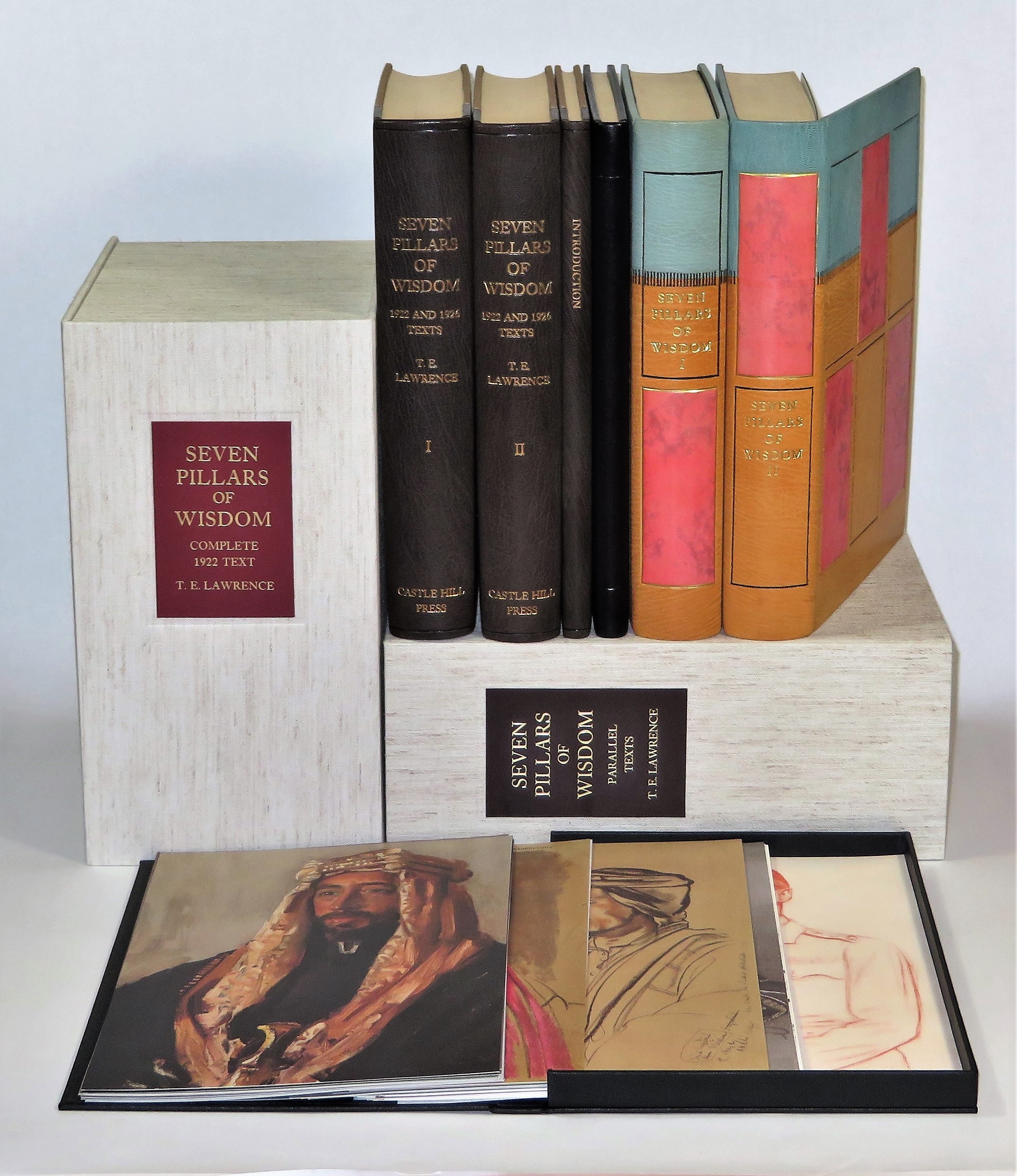

As for Seven Pillars of Wisdom, “I have no intention of writing anything more” was either a failure of candor or, more probably, indicative of the tempestuous oscillations in his perpetually unsettled feelings about publication. In 1926, a 250,000-word “Subscriber’s Edition” was produced by Lawrence – but fewer than 200 copies were made, each lavishly and uniquely bound. The process cost Lawrence far more than he made in subscriptions.

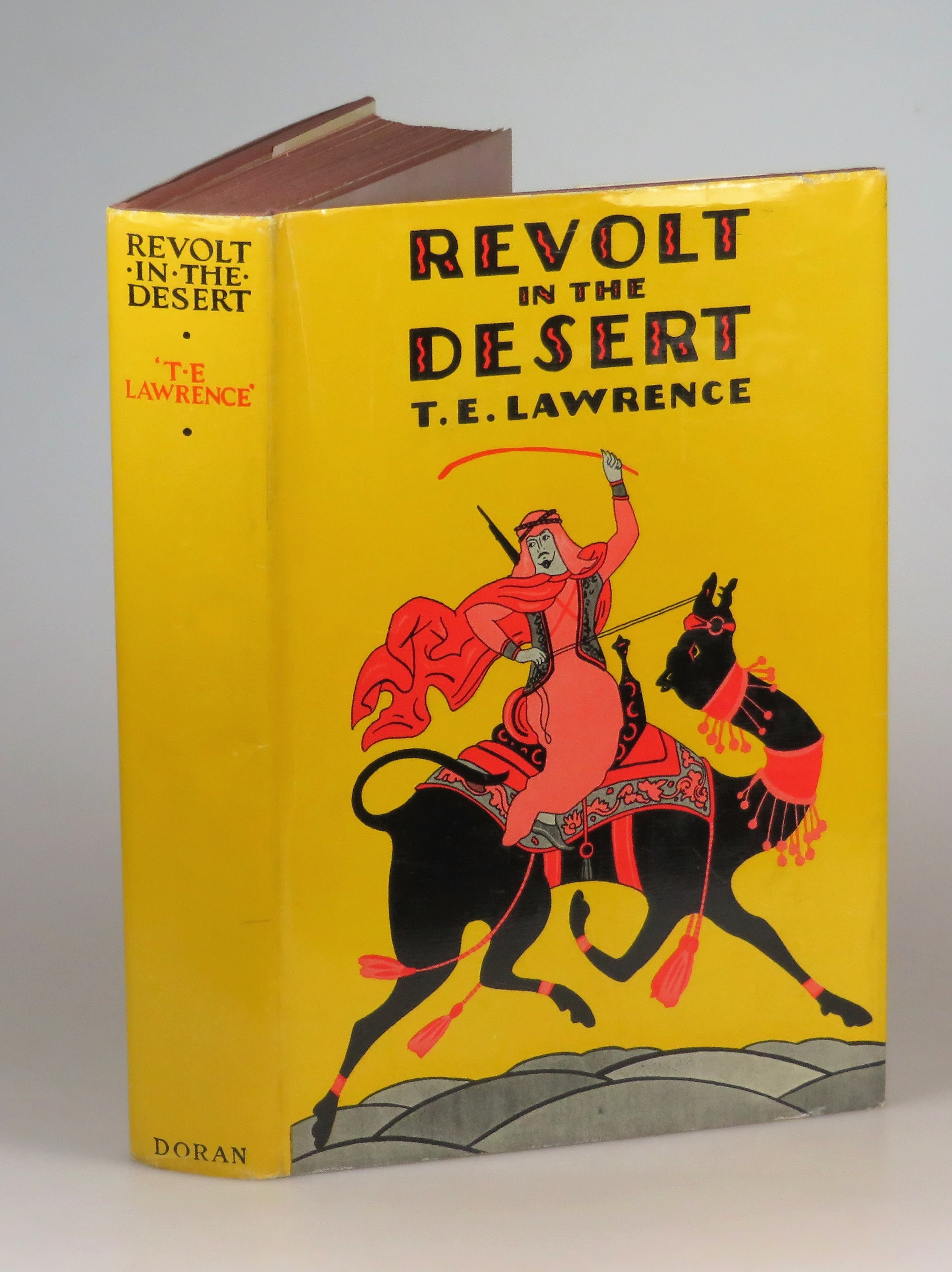

To recover the loss, Lawrence finally authorized an edition for the general public – but one even further abridged, titled Revolt in the Desert. It was only in the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, that the text of the Subscribers’ Edition was finally published for circulation to the general public. But the text released to the world as “Complete and Unabridged” in 1935 and which became so famous is, in fact, a significantly abridged version.

The considerably longer “account of the Arab Rebellion… in print (privately) some years ago” remained unpublished. Not until 1997 was the text referred to in this letter published in an edition available to the public. When the full text – 84,500 words longer – was finally prepared for publication, it was checked against the copy Lawrence surrendered to the Bodleian Library not long before writing this letter.

Today, we most often access and investigate Lawrence’s character through his published works. But it may be that Lawrence’s letters offer some of the clearest views. It is worth noting that after he wrote Lawrence’s official biography and published Lawrence’s long-suppressed Oxford Text, renowned Lawrence scholar Jeremy Wilson (1944-2017) spent many years collecting, editing, and publishing many volumes of Lawrence’s correspondence. Wilson knew Lawrence as well as anyone can or will. Perhaps Wilson recognized that the fragmentary candor and verities of Lawrence’s correspondence may best enable us to approach this singular, complex, and fascinatingly conflicted person.

Click HERE to view this letter on our website.