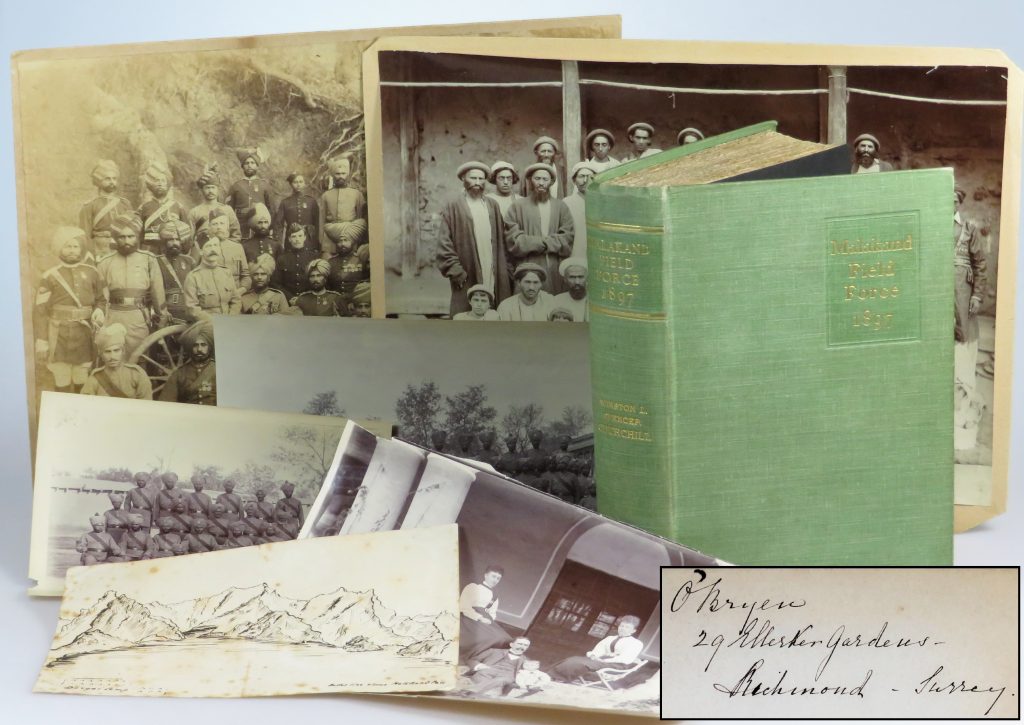

We recently acquired a remarkable association copy of the first edition of Winston Churchill’s first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force. This copy was owned by the bereaved family of Lieutenant-Colonel James Loughnan O’Bryen, whose death in action Churchill eloquently mourns within its pages. The book, noteworthy on its own merits for condition alone, not only has the association to O’Bryen’s family, but also came to us accompanied by a small archive including an original drawing of the Malakand Pass and five contemporary photographs depicting Colonel O’Bryen, his 30th Punjabi Regiment, and what appears to be a native militia.

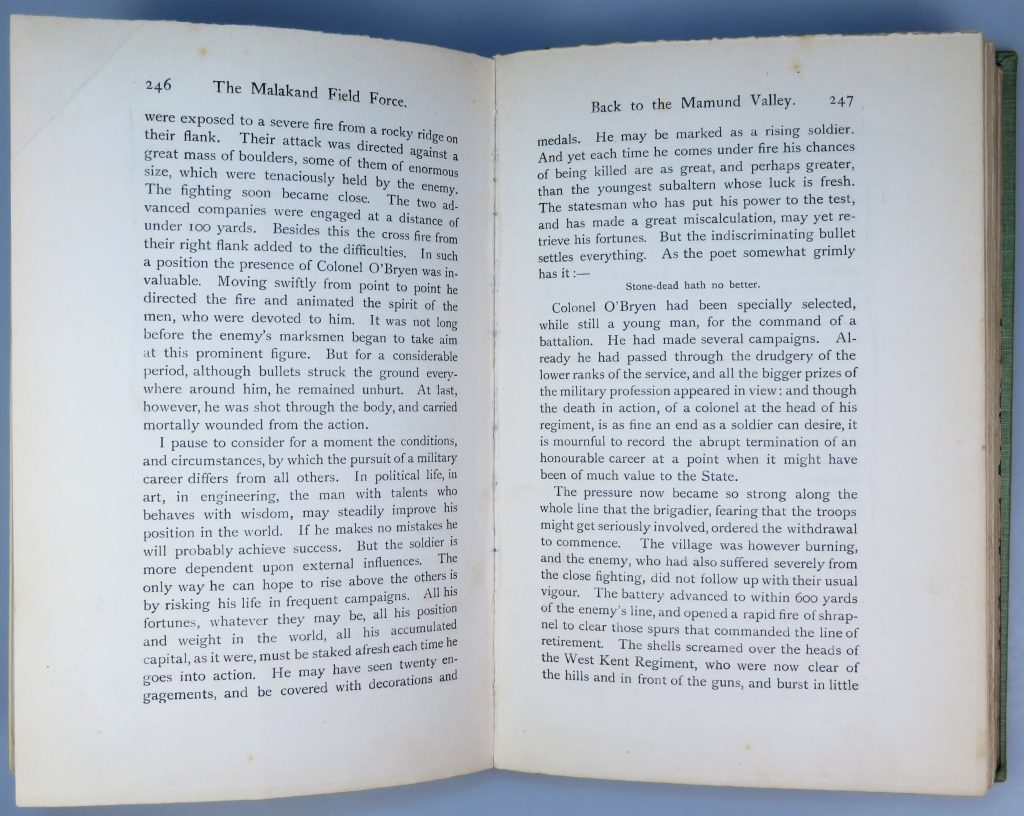

At pages 245-7 of his first published book, Churchill wrote:

Meanwhile the 31st Punjaub Infantry, who had advanced under Colonel O’Bryen on the right, were exposed to a severe fire from a rocky ridge on their flank. Their attack was directed against a great mass of boulders, some of them of enormous size, which were tenaciously held by the enemy. The fighting soon became close. The two advanced companies were engaged at a distance of under 100 yards. Besides this the cross fire from their right flank added to their difficulties. In such a position the presence of Colonel O’Bryen was invaluable. Moving swiftly from point to point, he directed the fire and animated the spirit of the men, who were devoted to him. It was not long before the enemy’s marksmen began to take aim at this prominent figure. But for a considerable period, although bullets struck the ground everywhere around him, he remained unhurt. At last, however, he was shot through the body, and carried mortally wounded from the action.

I pause to consider for a moment the conditions, and circumstances, by which the pursuit of a military career differs from all others. In political life, in art, in engineering, the man with talents who behaves with wisdom may steadily improve his position in the world. If he makes no mistakes he will probably achieve success. But the soldier is more dependent upon external influences. The only way he can hope to rise above the others, is by risking his life in frequent campaigns. All his fortunes, whatever they may be, all his position and weight in the world, all his accumulated capital, as it were, must be staked afresh each time he goes into action. He may have seen twenty engagements, and be covered with decorations and medals. He may be marked as a rising soldier. And yet each time he comes under fire his chances of being killed are as great as, and perhaps greater than, those of the youngest subaltern, whose luck is fresh. The statesman, who has put his power to the test, and made a great miscalculation, may yet retrieve his fortunes. But the indiscriminating bullet settles everything. As the poet somewhat grimly has it:—

Stone-dead hath no better.

Colonel O’Bryen had been specially selected, while still a young man, for the command of a battalion. He had made several campaigns. Already he had passed through the drudgery of the lower ranks of the service, and all the bigger prizes of the military profession appeared in view: and though the death in action of a colonel at the head of his regiment is as fine an end as a soldier can desire, it is mournful to record the abrupt termination of an honourable career at a point when it might have been of much value to the State.

Battlefield sentiment was not an abstract concept to Churchill. A combination of youthful exuberance, political ambition, sense of destiny, and need to prove his mettle – we leave to others the task of determining the exact proportions of each – put Churchill decisively in harm’s way on the same 1897 battlefields of the colonial northwest Indian frontier. The fate of those, like O’Bryen, who faced the same risks on the same battlefields impressed upon Churchill the potentially dire cost of this particular type of ambition.

Churchill’s memorial to O’Bryen is remarkable in several respects. Like Thucydides long before him and many others writing in the intervening millennia, Churchill clearly regards the role of chance in warfare. Moreover, Churchill shows a deep respect for those who risk all in battle. But below the eloquent philosophy and homage are manifest aspects of the self-focused, very young man Churchill was. Clearly on display is the driving force of his as-yet unrealized political ambition – even in this memorial, Churchill cannot resist articulating the metaphor of “The statesman, who has put his power to the test, and made a great miscalculation” but “may yet retrieve his fortunes.” The metaphor would, of course, prove particularly prophetic for Churchill… Also on display is the nascent, apparently instinctive Churchillian gift for nobly framing events and setting them in greater context. But while Churchill’s talents and ambition are both clearly on display, so too are the limitations of his youth and experience. The conclusion – “…it is mournful to record the abrupt termination of an honourable career at a point when it might have been of much value to the State.” – cannot help but strike this reader as thuddingly detached and unsympathetic. O’Bryen left behind not only his “honourable career” and potential use to the State, but also a wife, a daughter, and the full measure of his own perspectives and passions. Before winning the Nobel Prize in Literature more than half a century later “for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.“, Churchill would risk, lose, achieve, and suffer much – and in the process learn to do better.

Churchill’s words about the unfortunate Lt. Colonel O’Bryen apparently reached his surviving wife and daughter. The sole previous ownership mark in this copy is three lines, inked on the half title: “O’Bryen | 29 Ellerker Gardens | Richmond-Surrey”. The ownership mark was almost certainly made by O’Bryen’s wife or daughter; the only other marks in the book are a folded upper corner at the p.245-6 leaf and faint pencil lines in the margins beside text giving Churchill’s account of O’Bryen’s death. The book is a beautifully clean copy of the first edition, only printing, its preservation thus substantiating the notion that it was a family memento of significance. Confirming that supposition are the original drawing and five photographs of O’Bryen and his 30th Punjabi Regiment that accompanied this book.

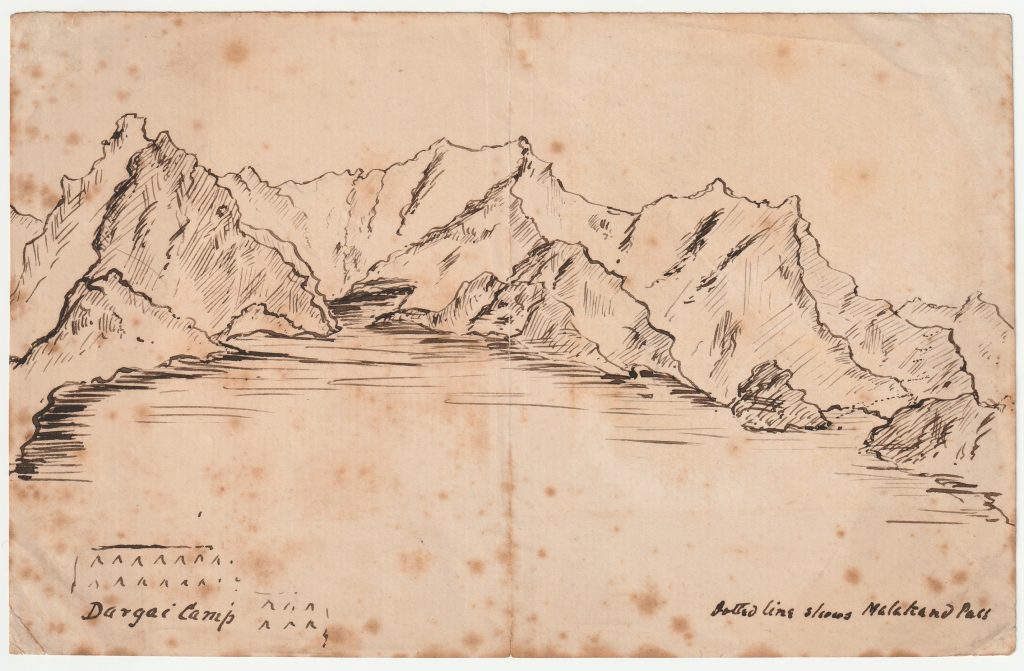

An unsigned drawing depicting “Malakand Pass” is in black ink on a 4.5 x 7 inch piece of laid paper, folded once and spotted. The lower left of the drawing has what are presumably triangular representations of tents captioned “Dargai Camp”. At the lower right, the drawing is captioned “Dotted line shows Malakand Pass”. (The dotted line in question is at the right portion of the drawing 1.5 inches above the caption.) Though we cannot confirm the identity of the drawing’s creator, it is certainly contemporary and has kept company all this time with the other personal effects of O’Bryen.

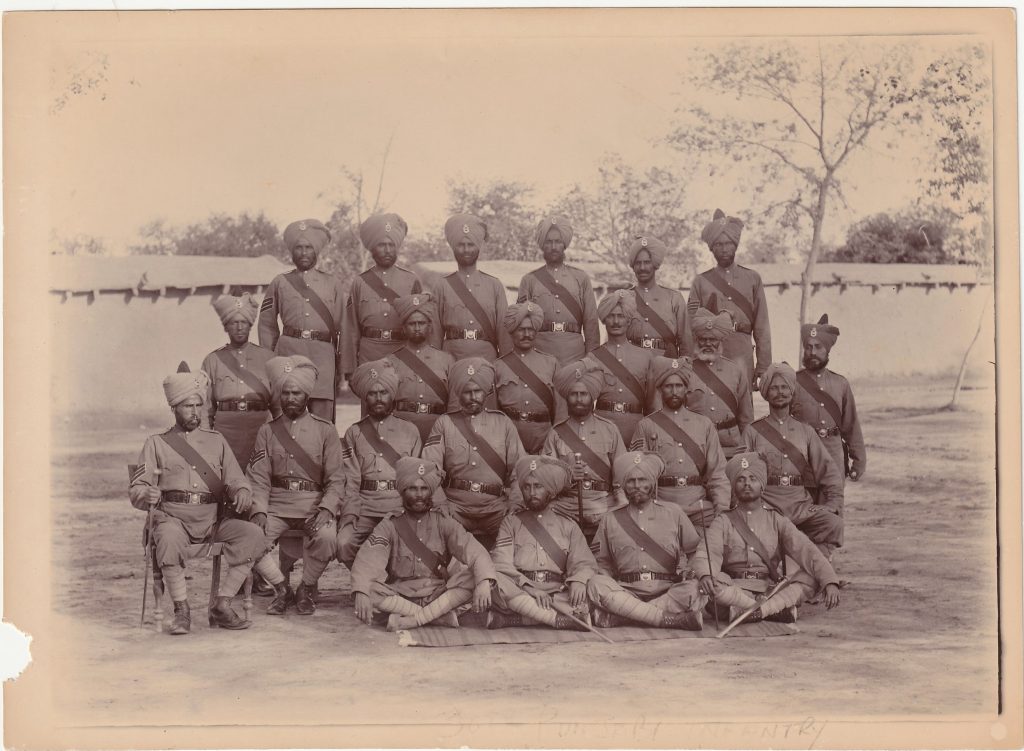

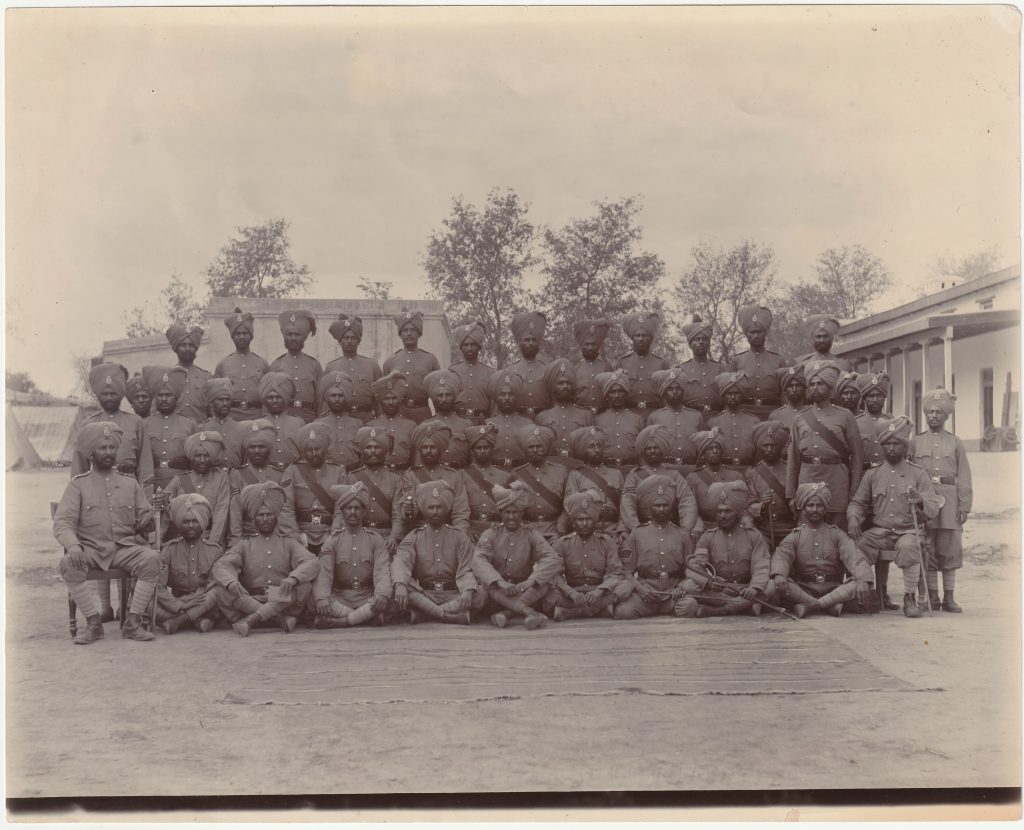

The five photographs are decisively those of Lt. Colonel O’Bryen, two of them depicting him and two of them the men of the regiments in which O’Bryen served. There is a silver gelatin group portrait of the 30th Punjabi Infantry in uniform. This is a very clean, high contrast image measuring 4.75 x 6.75 inches with a small piece missing from the lower left blank margin. A penciled caption at the bottom of the photograph reads: “30th PUNJABI INFANTRY”.

Another, larger silver gelatin group portrait of the 30th Punjabi Infantry in uniform set against a different background. Though this group of soldiers is appreciably larger, some of the figures are recognizably the same, as are the uniforms. This photograph measures 6.5 x 8.125 inches is pencil captioned on the verso: “30th PUNJABI INFANTRY”.

The sole non-military silver gelatin photograph, measuring 6.25 x 8.125 inches, is a study in Victorian colonial casual archetype. Colonel O’Bryen in a suit is sprawling on porch stairs, hand in pocket, double-breasted waistcoat exposed, legs crossed, with a child leaning against him and two women in voluminous skirts seated in chairs on the porch above him to the left and right. The photo is clean, though with irregular breaks to the brittle paper along the top and left edges, a triangular loss at the lower left corner, and a short, closed tear at the bottom edge.

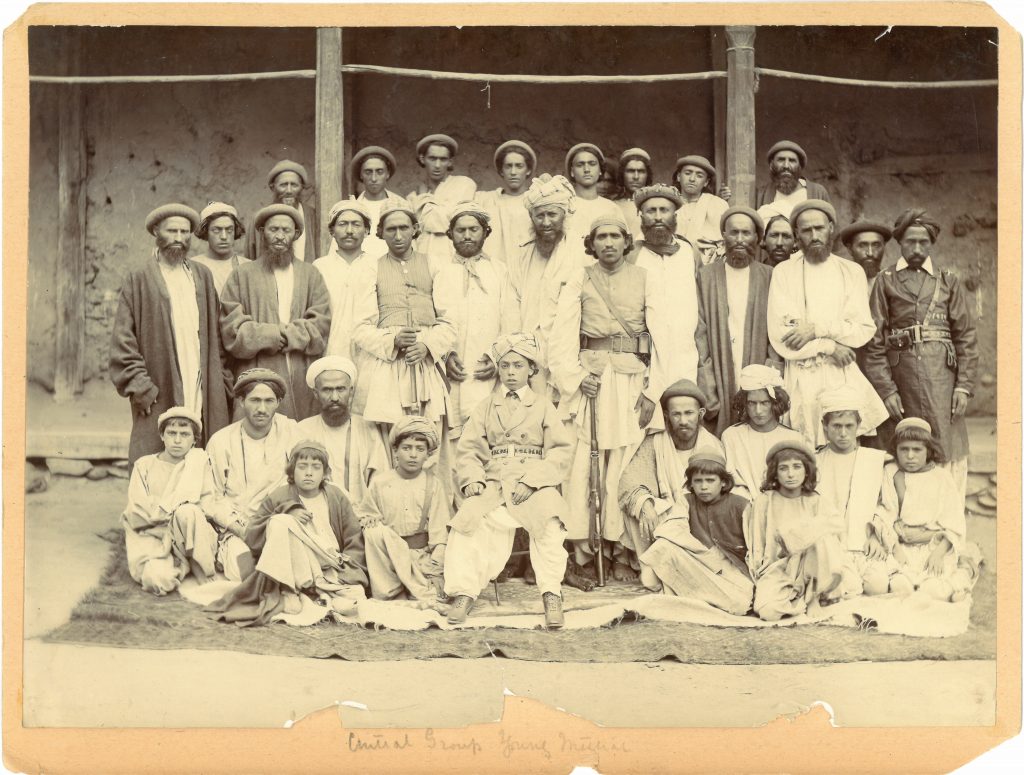

An 8.5 x 11.25 silver gelatin portrait of un-uniformed men and boys, some of the men visibly armed, is captioned in pencil “Central Group Young [illegible]”. The final word, which we cannot definitively decipher, could plausibly be “Militia”. This clean, high contrast image is affixed to a mount at the corners and has irregular breaks to the brittle paper along the bottom edge, not affecting the figures depicted therein. This photograph is ink-stamped on the verso: “Gillmore T Carte | Dalhousie, Punjaub | photographer”.

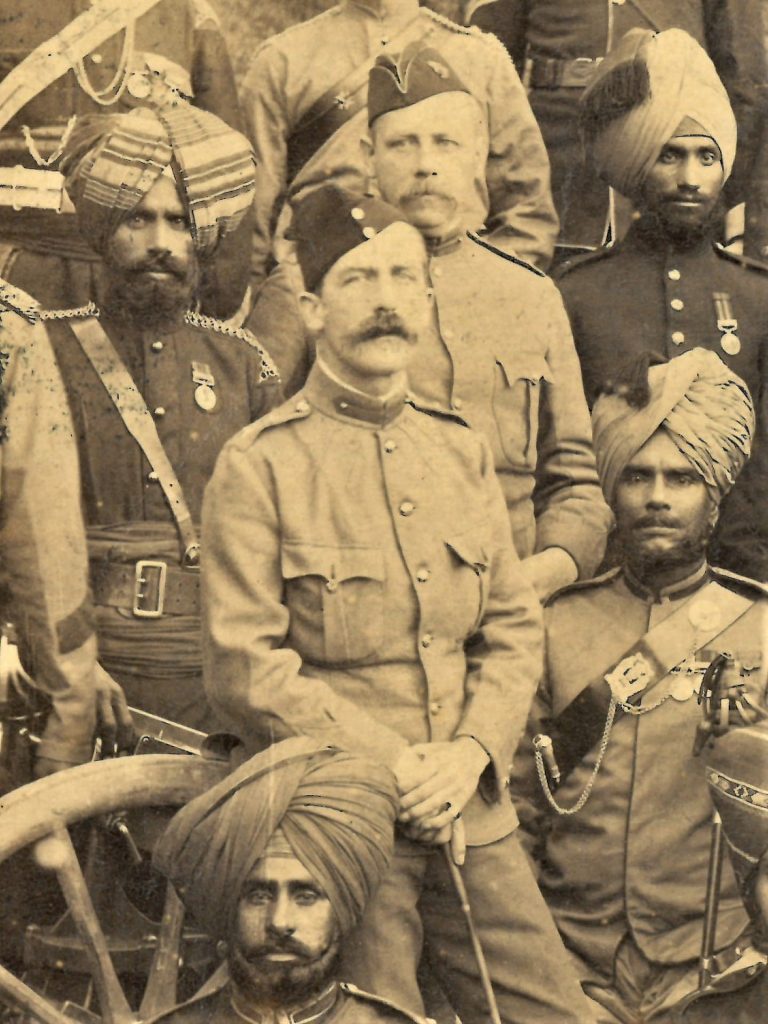

A large, 9.25 x 11.25 inch albumen group portrait is arguably the standout piece of the collection, depicting four rows of native soldiers with their British officers intermixed, Colonel O’Bryen prominent among them. The photograph is captioned in pencil at the bottom: “COL OBRYEN WHITE OFFICER 2 ROW THIRD FROM LEFT / 5th AND 30TH PUNJABI INFANTRY”. The lower right is signed in the print “F. Winter”. Winter was a photographer in Muree, Punjab.

Lieutenant-Colonel James Loughnan O’Bryen was born in Delhi, India on 8 January 1854. His father was a decorated Colonel with the Indian Staff Corps who served in the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845-6. James was evidently sent to England for his education as he was recorded in the 1871 UK census as a 17-year-old scholar in a London household and there is evidence that he attended the Downside school in Somerset. His service papers in the National Archive indicate that he first entered into the Army at “20 1/12” years with the 11th Infantry Regiment in 1874 (the year Churchill was born) before joining the Indian Staff Corps in 1876. In 1879 he served during the Afghan War with the Kandahar and Khyber Field Forces. He also served in the Third Anglo-Burmese War, General Lockharts’s expedition against the Isazai tribes, and in the Chitral expedition. In 1894 O’Bryen obtained his majority with the Indian Staff Corps and was placed second in command of the 30th Punjabis before he was appointed to command of the 31st Punjab Regiment of the Bengal Infantry on 5 August 1897. Less than two months later he was killed in action.

O’Bryen was survived by his wife and one daughter, to whom this book and images ostensibly belonged. After his death, O’Bryen’s body was recovered and moved to Peshawar, where he was buried with full honors and commemorated with a simple plaque reading: “In memory of Lieutenant Colonel James Loughnan O’Bryen, Commandant 31st PI who was killed in action at the head of his Regiment at Agrah in the Mamund Valley, Bajaur on 30th September 1897. Aged 43 years. Deeply regretted by his brother officers by whom this tablet is erected.”

Churchill’s own story would be written quite differently. And, beginning with this book, substantially written by his own hand.

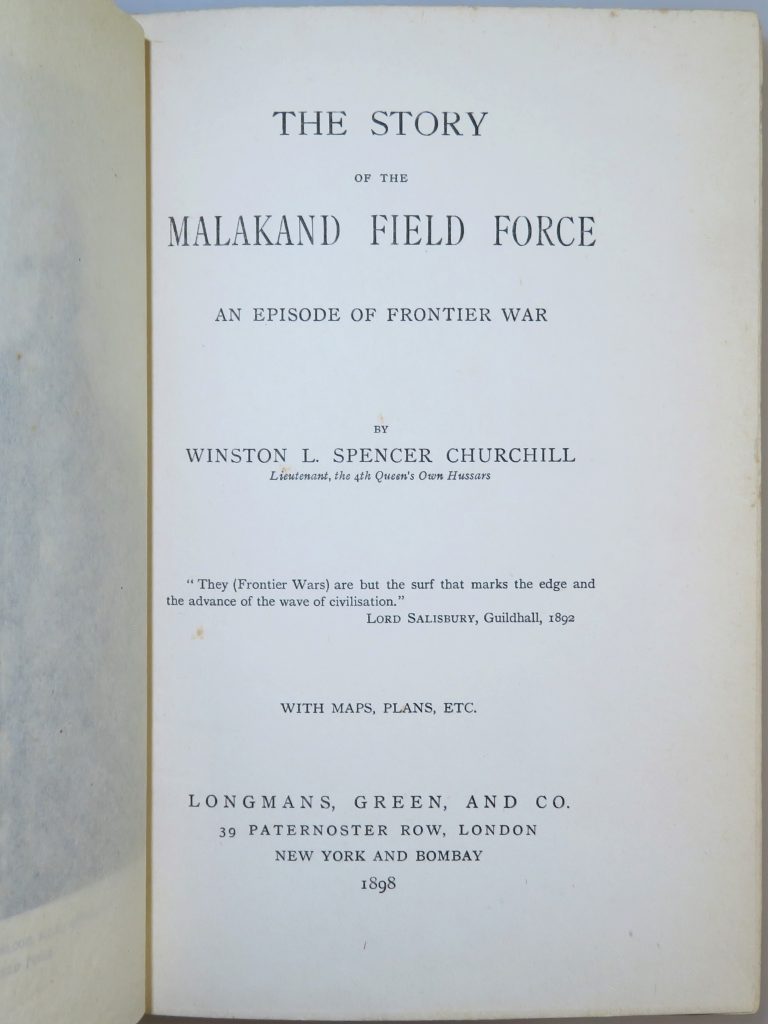

When this book was written and published, Churchill was a young cavalry officer still serving in India. While he had successfully applied his pen as a war correspondent – indeed the book is based on his dispatches to the Daily Telegraph and the Pioneer Mail – this was his first book-length work. The young Churchill was motivated by a combination of pique and ambition. He was vexed that his Daily Telegraph columns were to be published unsigned. On 25 October 1897 Churchill wrote to his mother: “…I had written them with the design… of bringing my personality before the electorate.” Two weeks later, his resolve to write a book firming, Churchill again wrote to his mother: “…It is a great undertaking but if carried out will yield substantial results in every way, financially, politically, and even, though do I care a damn, militarily.” Having invested his ambition in this first book, he clearly labored over it: “I have discovered a great power of application which I did not think I possessed. For two months I have worked not less than five hours a day.” The finished manuscript was sent to his mother on the last day of 1897 and published on 14 March of 1898.

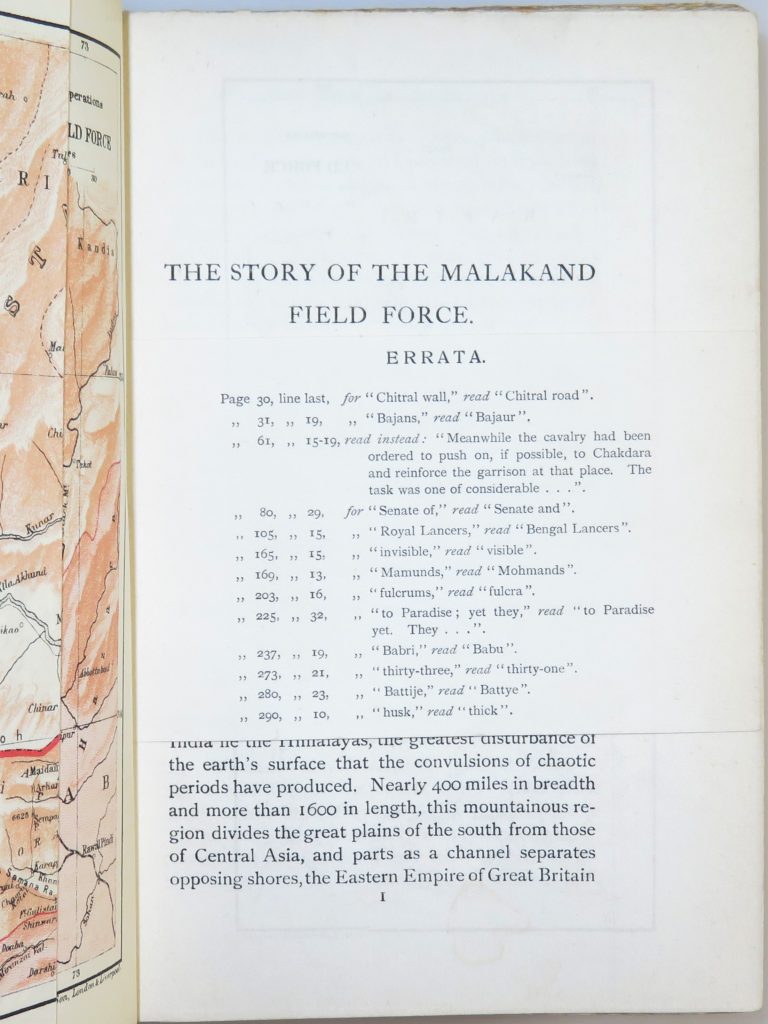

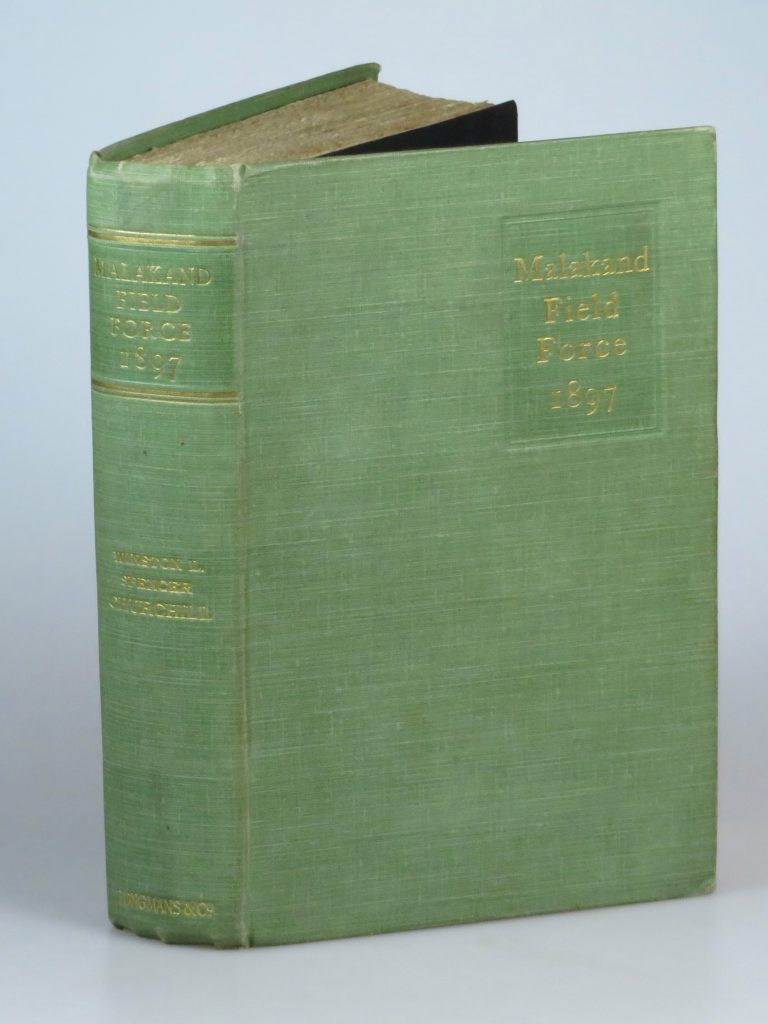

Publication was arranged by Churchill’s uncle while the author was still in India, resulting in numerous spelling and detail errors. Churchill was incensed by the errors and acted with haste to address them. Hence later states of the first edition bear errata slips. Home Issue copies also bear a 32-page Longmans, Green catalogue bound in at the back, which is dated either “12/97” or “3/98” at the foot of page 32. With only a little more than 1,900 copies bound, this first edition of Churchill’s first book is both desirable and elusive. The O’Bryen copy is an early second state, featuring the tipped-in errata slip and a rear catalogue dated “12/97”.

Apart from being an association copy, it is noteworthy for condition alone, approaching near fine. The publisher’s green cloth binding remains square, tight, clean, and beautifully bright with no discernible color shift between the spine and covers. We note only trivial wear to the hinges and corners and some minor wrinkling at the spine ends. The gilt on both front cover and spine remains vividly bright.

The contents are equally and notably clean for the edition, atypically bright. Some incidental spotting is confined to the page edges, which are otherwise clean with only mild age-toning. All maps are intact, including the folding maps at pages 1 and 146, as is the frontispiece and tissue guard. The original black endpapers are present and intact, with none of the typical cracking or splitting. While the mull is visible in the gutter following the endpapers and half title, this is strictly a cosmetic issue and in no way affects binding integrity.