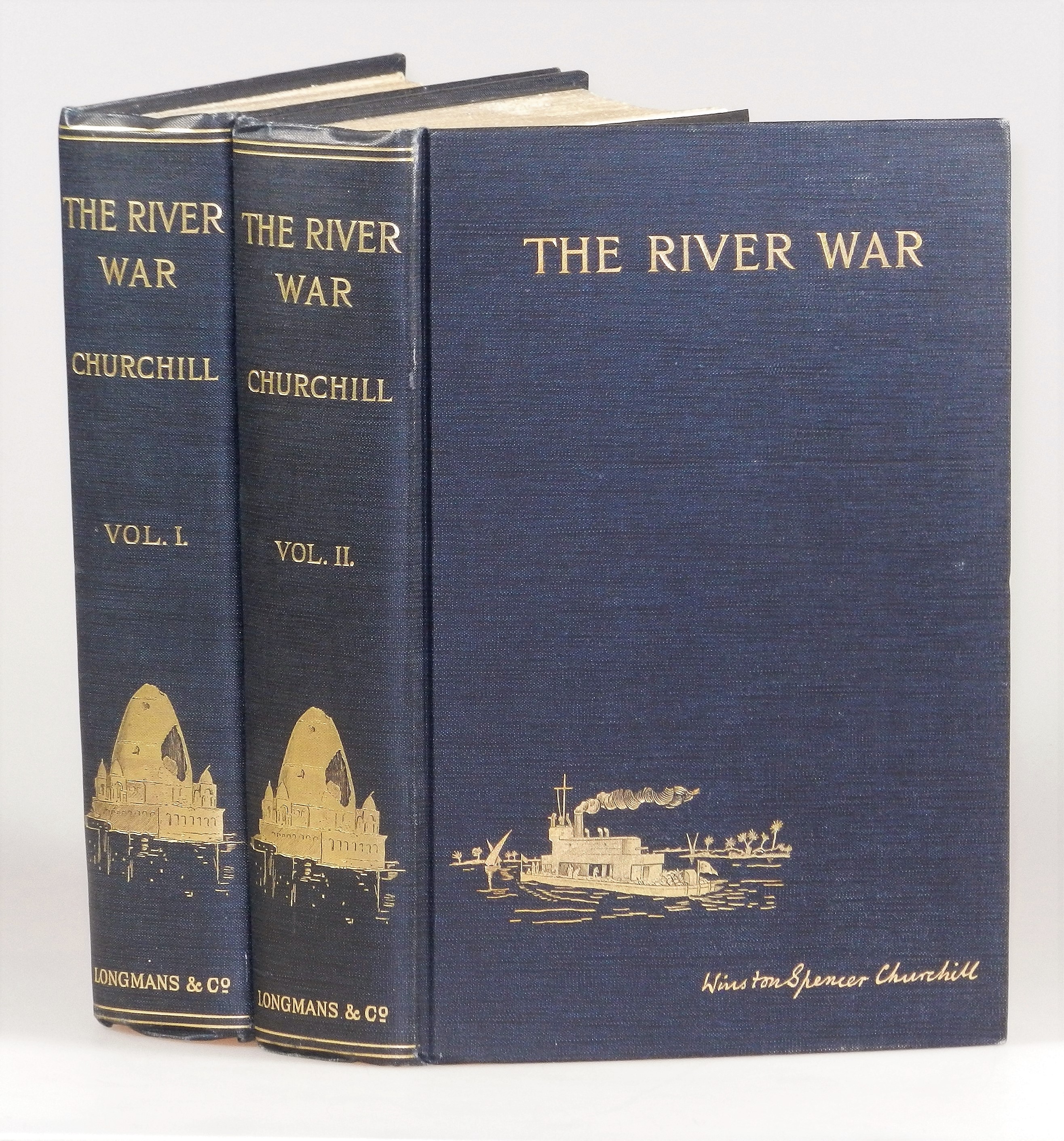

Churchill’s second published book – The River War – presents a singular and strange case in the vast canon of Churchill’s published books.

Originally published in 1899, it swiftly saw a new edition in 1902. But that edition was considerably abridged and revised by the author, the text significantly reduced by one-third. While corrections were made, the chief spur to abridgement was indicated in the author’s own Preface: “What has been jettisoned consists mainly of personal impressions and opinions, often controversial in character…” Churchill had been elected to Parliament in 1900, and, among other things, the legitimate but impolitic criticisms of imperial cynicism and cruelty made in the first edition were a liability.

That’s understandable. Puzzling is the fact that every single edition of The River War since – and there have been many – has been based on the 1902 abridged and revised text. That means that anyone wanting to read the full text has been obliged to subject a scarce, expensive, and precious first edition to the rigors of casual reading.

Until now.

Today we have invited Professor James W. “Jim” Muller for a guest post. Professor Muller writes about the forthcoming complete, unabridged, fully annotated edition of The River War. It is the first time in nearly 120 years that the full text will be published.

Dear Marc,

Thank you for the opportunity to let the Churchill community know about the forthcoming St. Augustine’s Press edition of The River War.

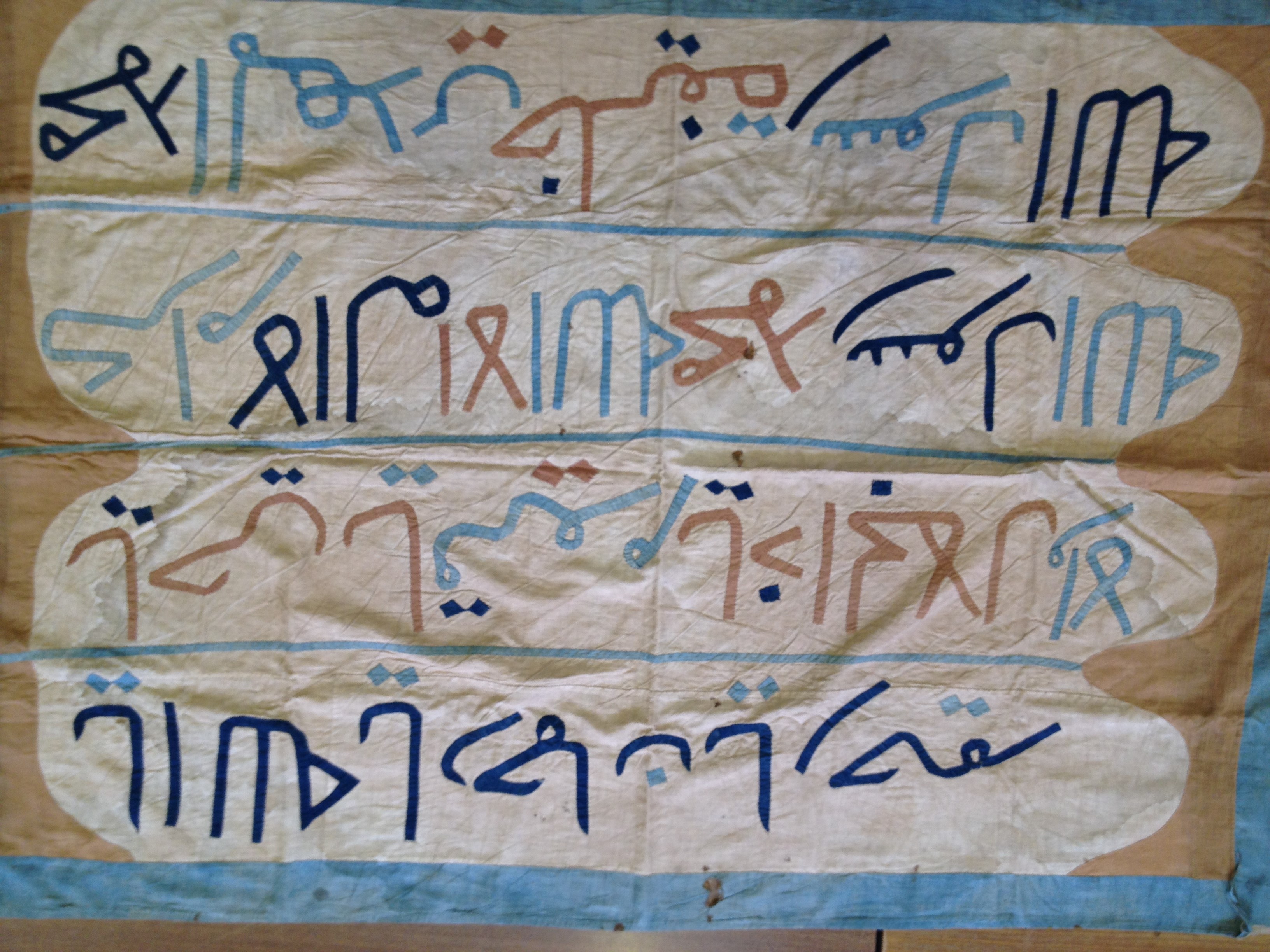

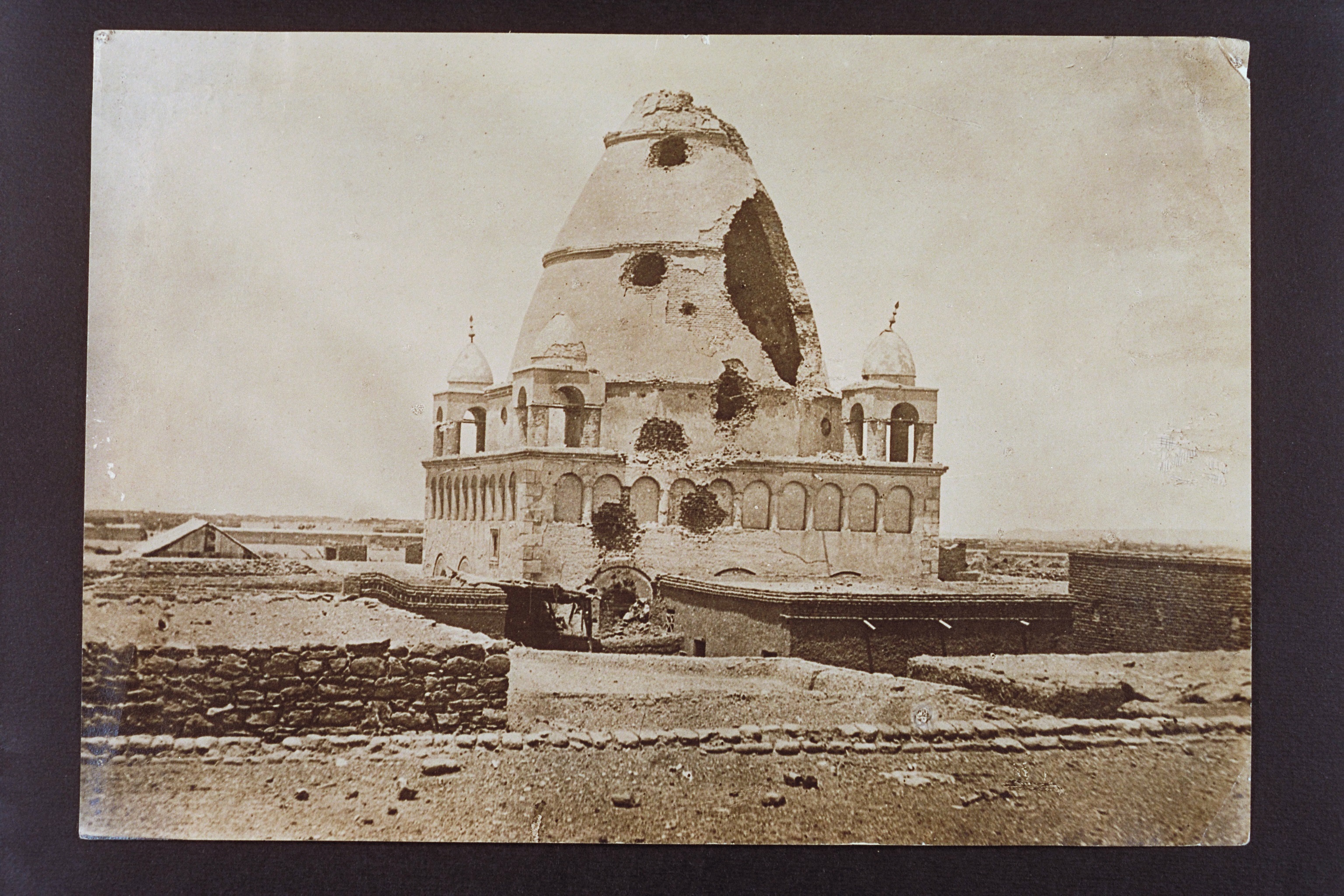

Winston Churchill wrote five books before he was elected to Parliament at the age of twenty-five. The most impressive of these books, The River War tells the story of Britain’s arduous and risky campaign to reconquer the Sudan at the end of the nineteenth century. More than half a century of subjection to Egypt had ended a decade earlier when Sudanese Dervishes rebelled against foreign rule and killed Britain’s envoy Charles Gordon at his palace in Khartoum in 1885. Political Islam collided with European imperialism. Herbert Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army, advancing hundreds of miles south along the Nile through the Sahara Desert, defeated the Dervish army at the battle of Omdurman on September 2, 1898.

Churchill, an ambitious young cavalry officer serving with his regiment in India, had already published newspaper columns and a book about fighting on the Afghan frontier. He yearned to join Kitchener’s campaign. But the general, afraid of what he would write about it, refused to have him. Churchill returned to London. With help from his mother and the prime minister, he managed to get himself attached to an English cavalry regiment sent to strengthen Kitchener’s army. Hurriedly travelling to Egypt, Churchill rushed upriver to Khartoum, catching up with Kitchener’s army just in time to take part in the climactic battle. That day he charged with the 21st Lancers in the most dangerous fighting against the Dervish host.

He wrote fifteen dispatches from the Sudan for the Morning Post in London. As Kitchener had expected, Churchill’s dispatches and his subsequent book were highly controversial. The precocious officer, having earlier seen war on two other continents, showed a cool independence of his commander-in-chief. He even resigned from the army to be free to write the book as he pleased. He gave Kitchener credit for his victory but found much to criticize in his character and campaign.

Churchill’s book, far from being just a military history, told the whole story of the Egyptian conquest of the Sudan and the Dervishes’ rebellion against imperial rule. The young author was remarkably even-handed, showing sympathy for the founder of the rebellion, Muhammad Ahmad, and for his successor the Khalifa Abdullahi, whom Kitchener had defeated. He considered how the war in northeast Africa affected British politics at home, fit into the geopolitical rivalry between Britain and France, and abruptly thrust the vast Sudan, with the largest territory in Africa, into an uncertain future in Britain’s orbit.

In November 1899, The River War was published in “two massive volumes, my magnum opus (up to date), upon which I had lavished a whole year of my life,” as Churchill recalled later in his autobiography. The book had twenty-six chapters, five appendices, dozens of illustrations, and colored maps.

Three years later, in 1902, it was shortened to fit into one volume. Seven whole chapters, and parts of every other chapter, disappeared in the abridgment. Many maps, most illustrations, and most appendices were also dropped. Since then the abridged edition has been reprinted regularly, and eventually it was even abridged further. But the full two-volume book, which is rare and expensive, was never published again—until now.

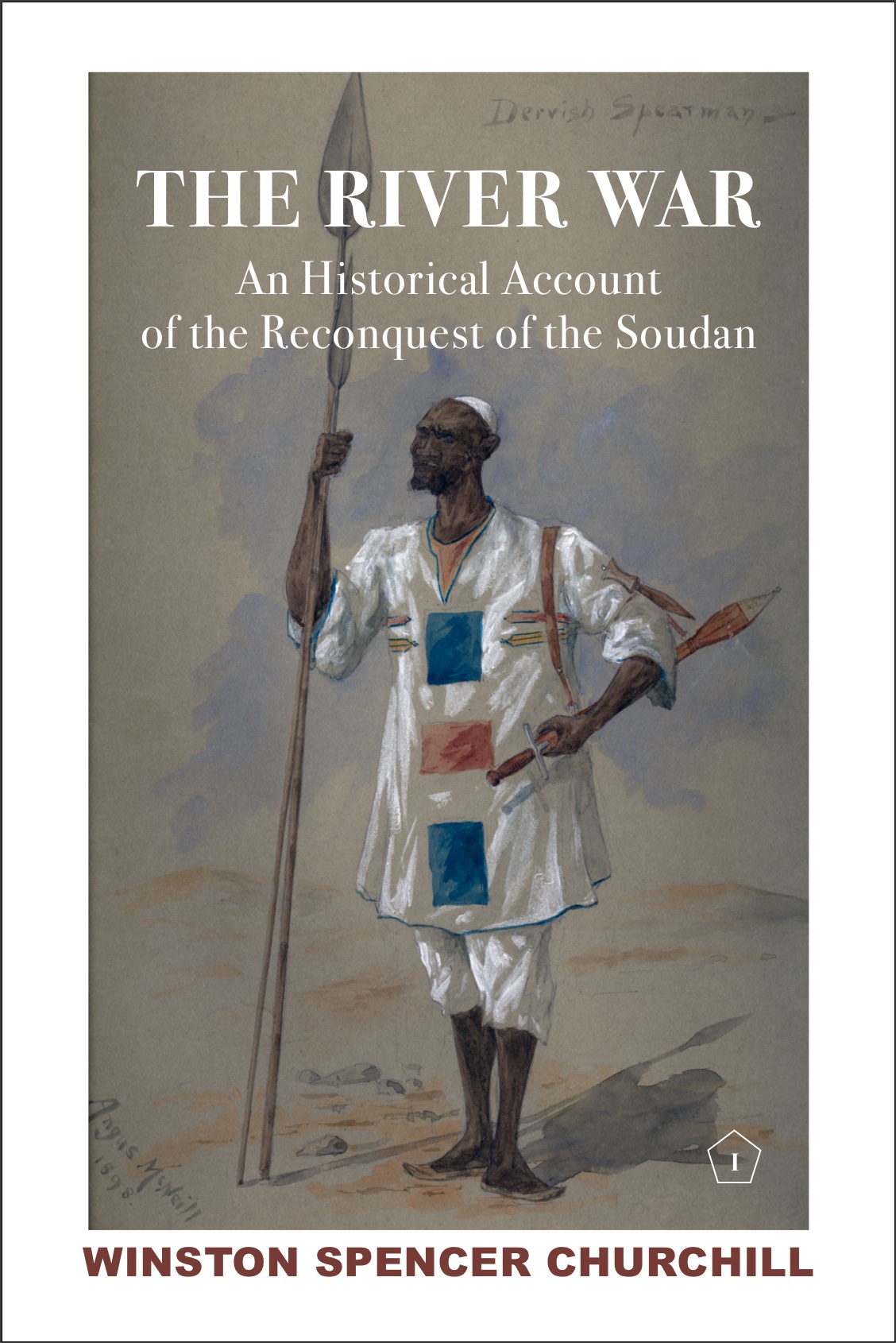

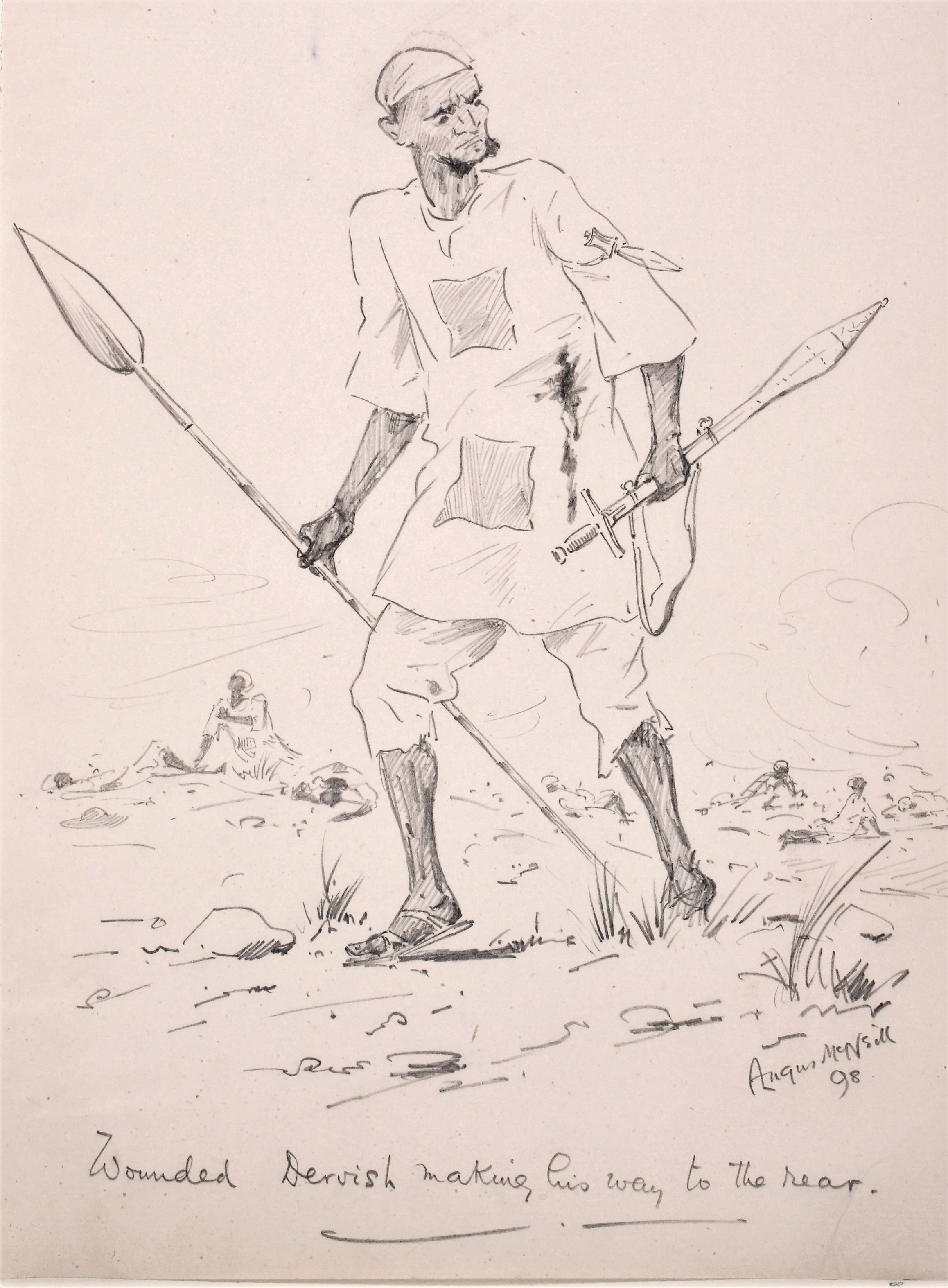

This fall, St. Augustine’s Press, in collaboration with the International Churchill Society, brings back to print in two handsome volumes The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan unabridged. Every chapter and appendix from the first edition has been restored. All the maps are in it, in their original colors, with all the illustrations by Churchill’s brother officer Angus McNeill.

This new edition of The River War has been more than thirty years in the making. I’ve created it to be the definitive edition. The whole book is printed in two colors, in black and red type, to show what Churchill originally wrote and how it was abridged or altered later. For the first time, a new appendix reproduces Churchill’s Sudan dispatches as he wrote them, before they were edited by the Morning Post. Other new appendices reprint Churchill’s subsequent writings on the Sudan. Thousands of new footnotes have been added to the book, identifying Churchill’s references to people, places, writings, and events unfamiliar to readers today. A new introduction explains how the book contributed to Churchill’s career as a writer and an aspiring politician and examines Churchill’s early thoughts about war, race, religion, and imperialism, which are still our political challenges in the twenty-first century.

Half a century after The River War appeared, this book was one of a handful of his works singled out by the Swedish Academy when it awarded Churchill the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953. Now, once again, its reader can follow Churchill back to the war he fought on the Nile, beginning with the words of his youngest daughter. Before she died, Mary Soames wrote a new foreword for this book, which concludes that “In this splendid new edition…we have, in effect, the whole history of The River War as Winston Churchill wrote it—and it makes memorable reading.”

With all best wishes,

Yours,

Jim

James W. Muller

Professor of Political Science

University of Alaska, Anchorage

There is a reason this work took long years to achieve publication.

Merely being the first unabridged edition in 120 years would justify some excitement. But this is far more than just an unabridged edition. Included in the edition are the following:

- Churchill’s original, unedited dispatches from the Sudan

- Churchill’s additional, later writings about the Sudan and its leaders

- Unpublished illustrations from a notebook kept during the campaign by the original artist of Churchill’s book, his fellow officer Angus McNeill

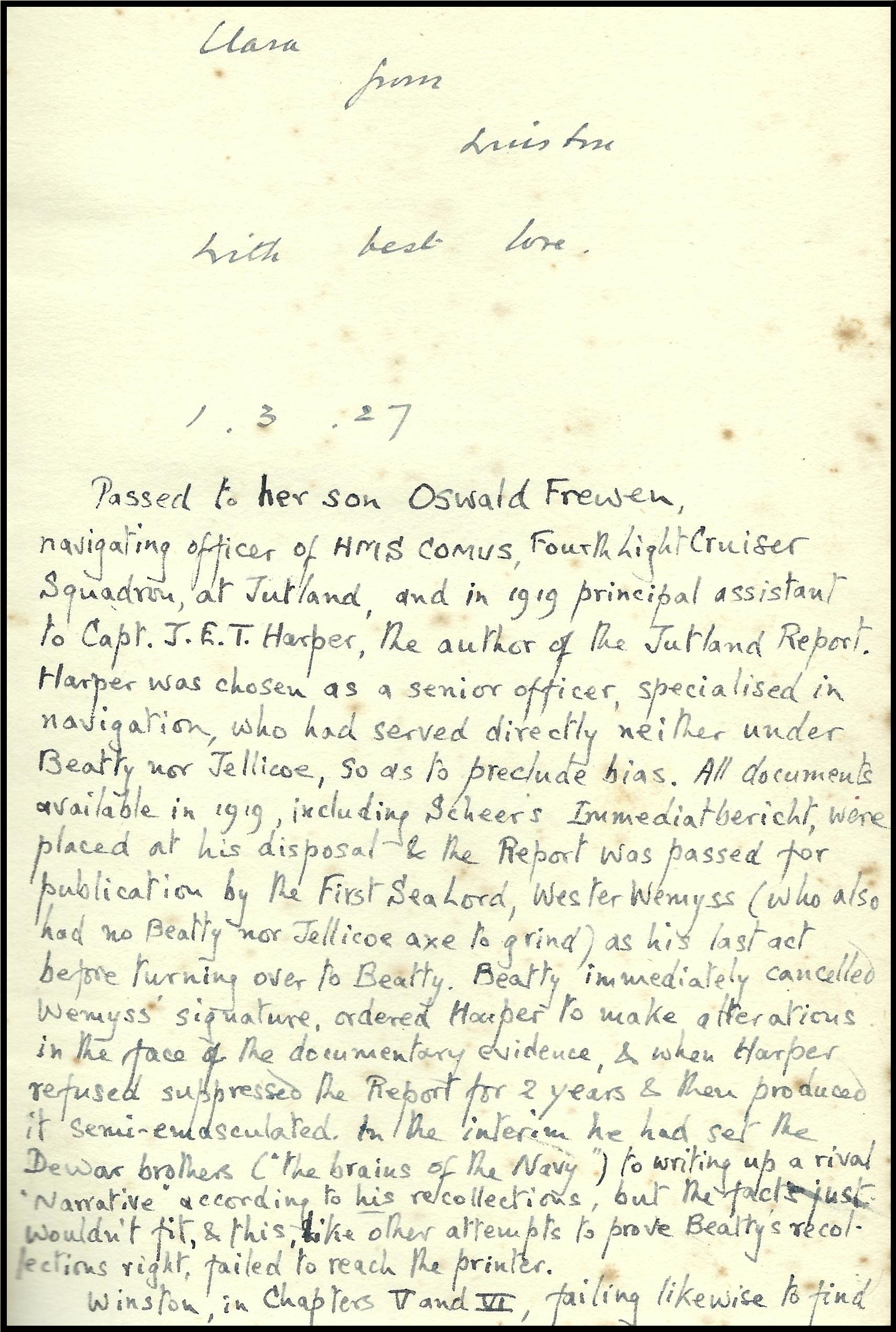

- A facsimile of Churchill’s original, handwritten draft of his chapter on the fate of Gordon – the only known chapter draft preserved in his hand

- Professor Muller’s extensive, insightful, and helpfully contextualizing Introduction

- Profuse and informative annotations footnoted throughout the work, identifying Churchill’s references to people, places, writings, and events unfamiliar to today’s readers.

- A new foreword, written specifically for this edition by Churchill’s youngest daughter, Mary Soames, before her death

Moreover, the entire text of The River War is printed in two colors, distinguishing between what Churchill originally wrote and how it was later abridged or altered.

The River War will be available in two forms.

A two-volume trade edition in a conventional hardcover binding will be available for $150. The trade issue dust jacket will feature a full-color drawing of a Dervish spearman by Angus McNeill (Volume I) and a photograph of Churchill in his Sudan uniform, which he signed on the day of the Battle of Omdurman (Volume II). Click HERE to reserve your copy with a deposit.

The finely bound, limited, and numbered Subscriber’s Issue

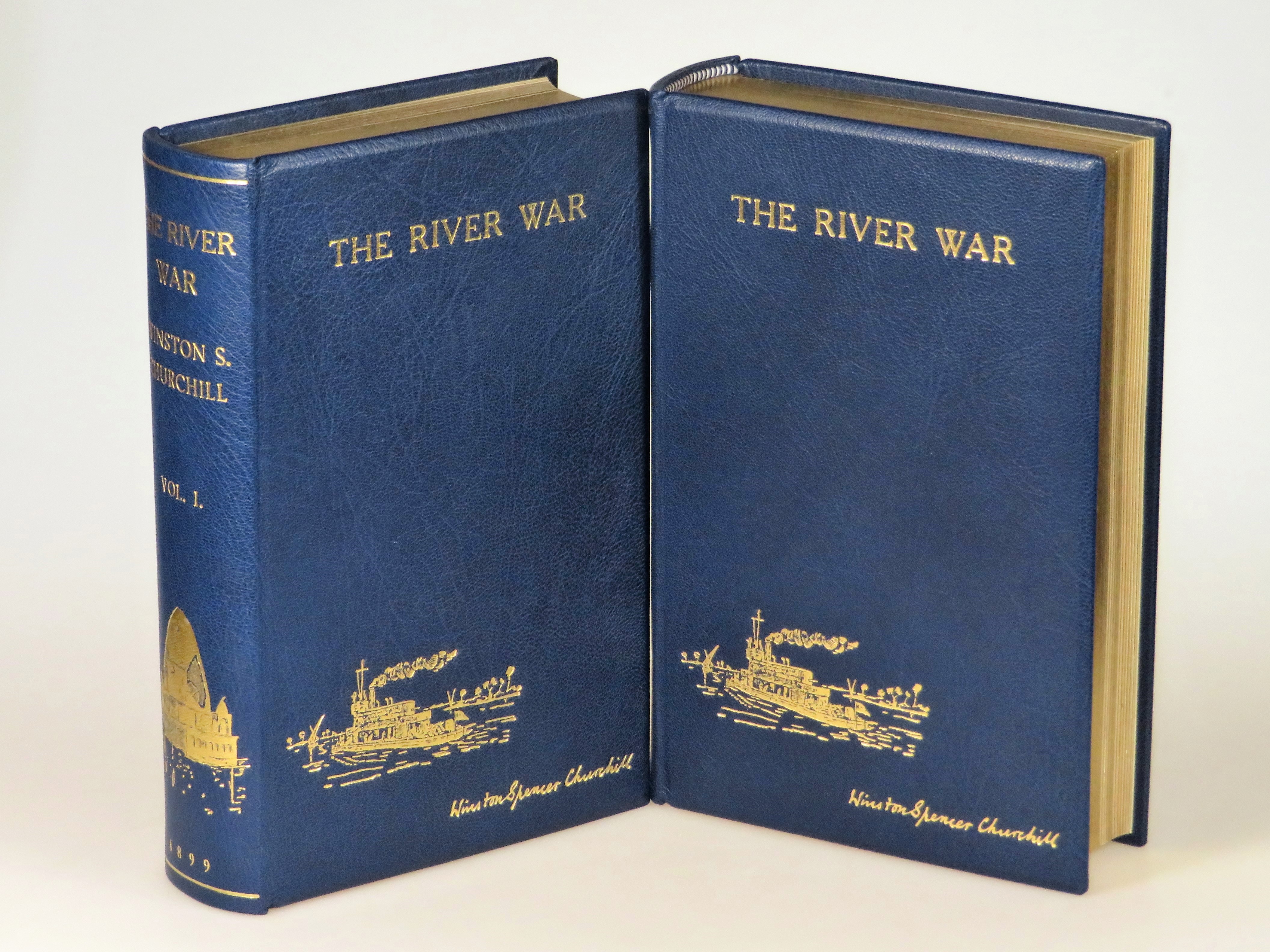

By special arrangement with the editor and publisher, Churchill Book Collector will offer a finely bound, limited, and numbered issue for subscribers.

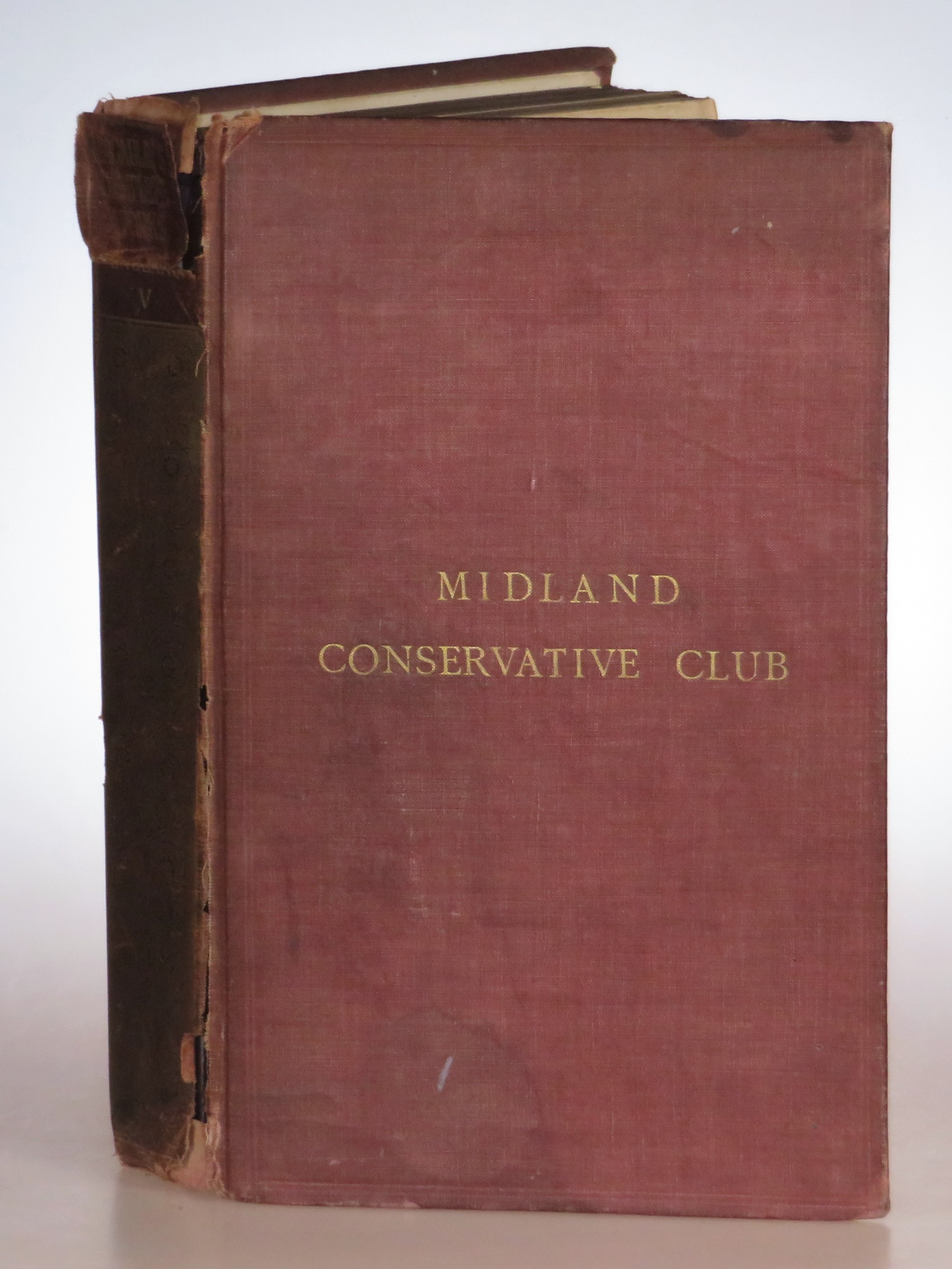

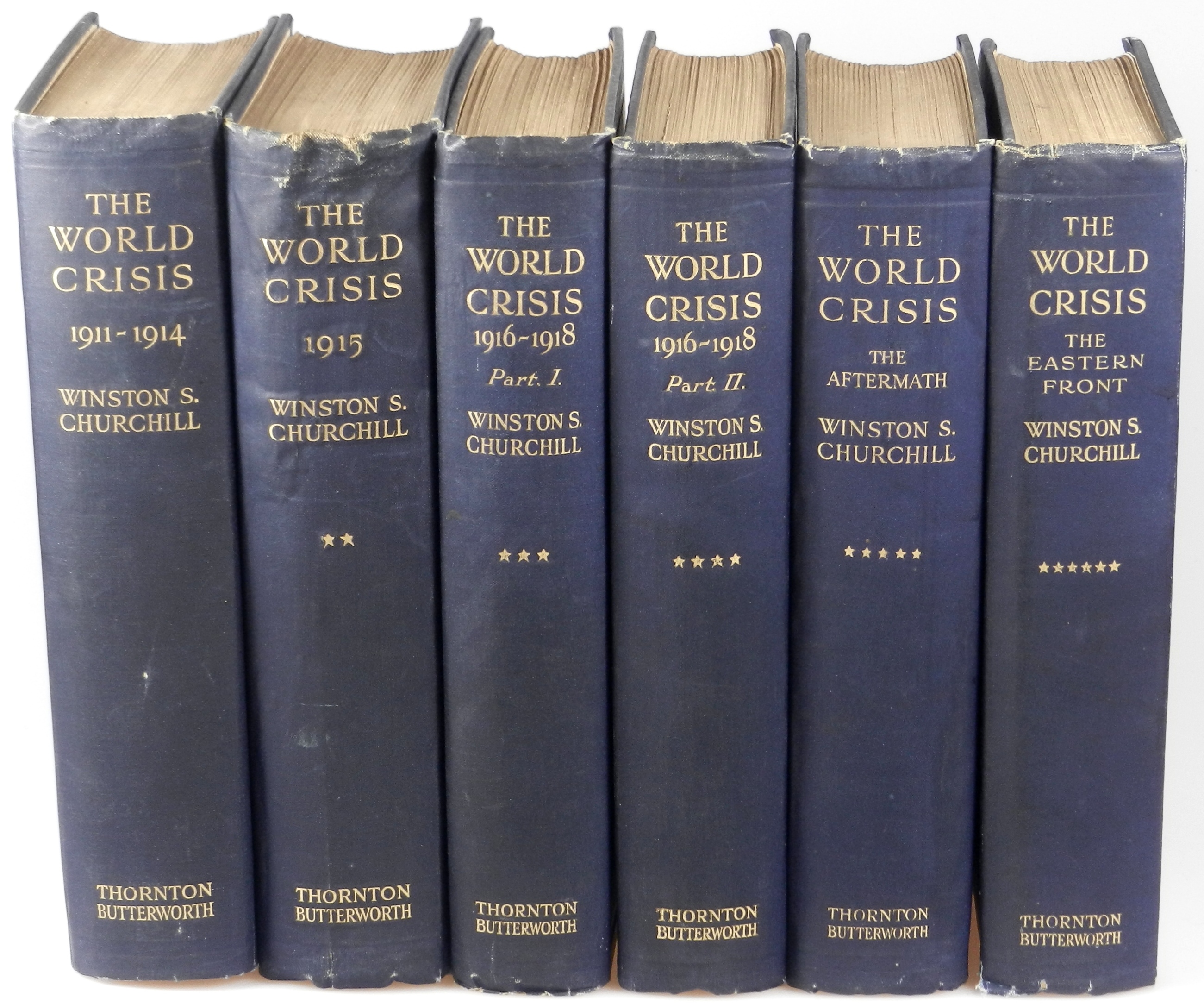

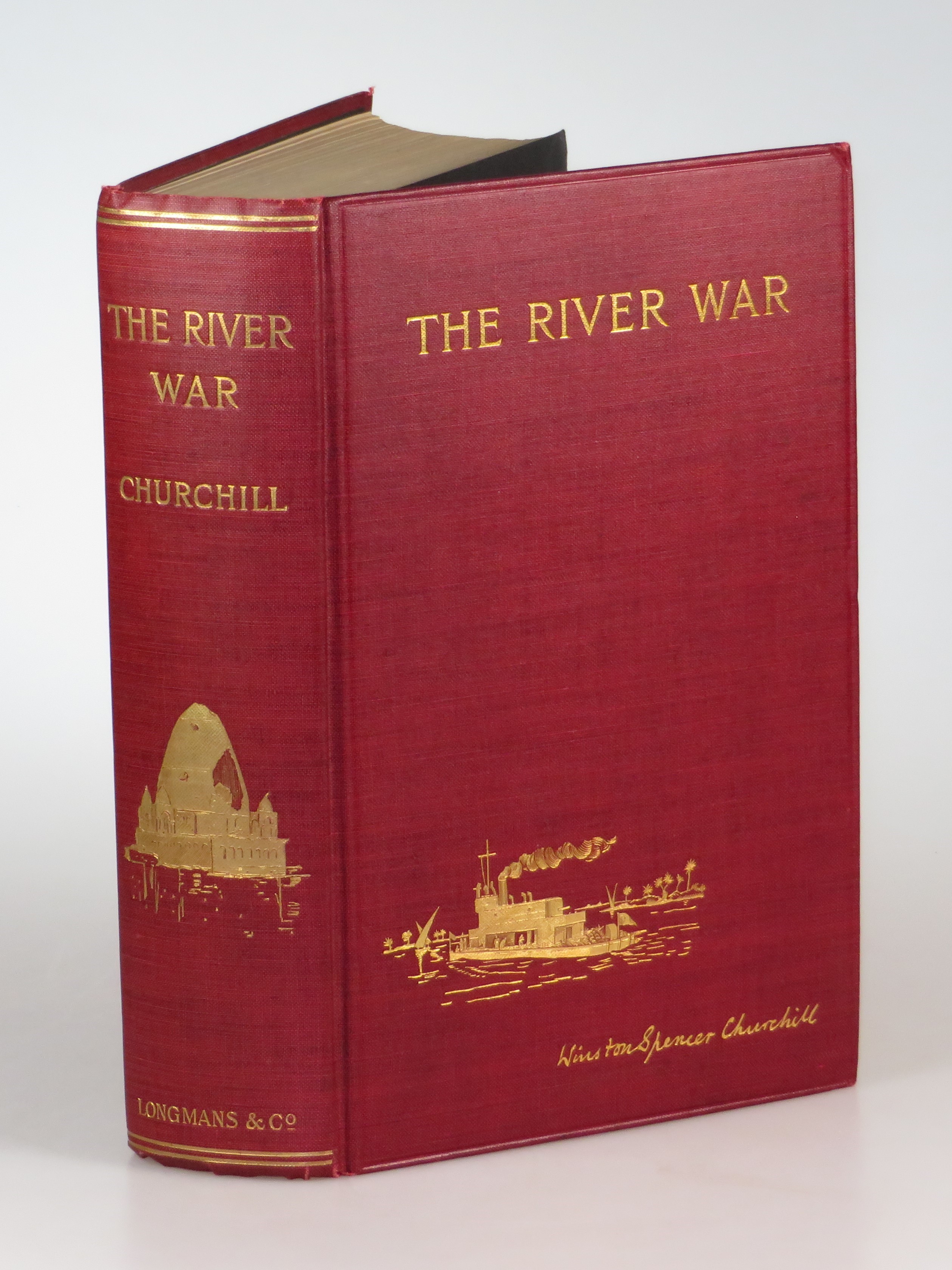

This Subscriber’s issue will be personally hand-bound by the proprietor of Felton Bookbinding Ltd. in full navy morocco goatskin deferential in color and design to the publisher’s original illustrated cloth. Both binding illustrations – the Mahdi’s tomb on the spines and the gunboat on the beveled-edge front covers – are recreated from newly commissioned artwork and dies. The contents will be sewn, bound with silk head and tail bands and all edges gilt. Gilt-ruled turn-ins will frame handsome marbled endpapers. The limitation page of each set will be hand-numbered and signed by the Editor. The volumes will be housed in a navy cloth slipcase. Appearance of the volumes will be similar to those pictured.

There will be no more than 50 copies of the Subscriber’s issue of The River War. Click HERE to reserve your copy with a deposit.

Cheers!