This post, prompted by new additions to our inventory, touches on four First World War poets – Brooke, Graves, Owen, and Sassoon – and the wounds, exhaustions, extinguishments, and scarred endurances these poets lived and expressed.

103 years ago tomorrow, at the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, the First World War ended. Much ink has spilled analyzing how the unprecedented carnage of the First World War fundamentally disrupted and reshaped social, political, and cultural conceptions. It turned out that even the spilling of ink was altered; the romantic conceits of poetry numbered among the many casualties of the First World War, and the changes wrought in some of the leading poetic voices became both reflection and herald of a terribly altered world. “Modernity”, with all of its cruel candor, was born of – and borne by – poetry and poets as much as the battlefields.

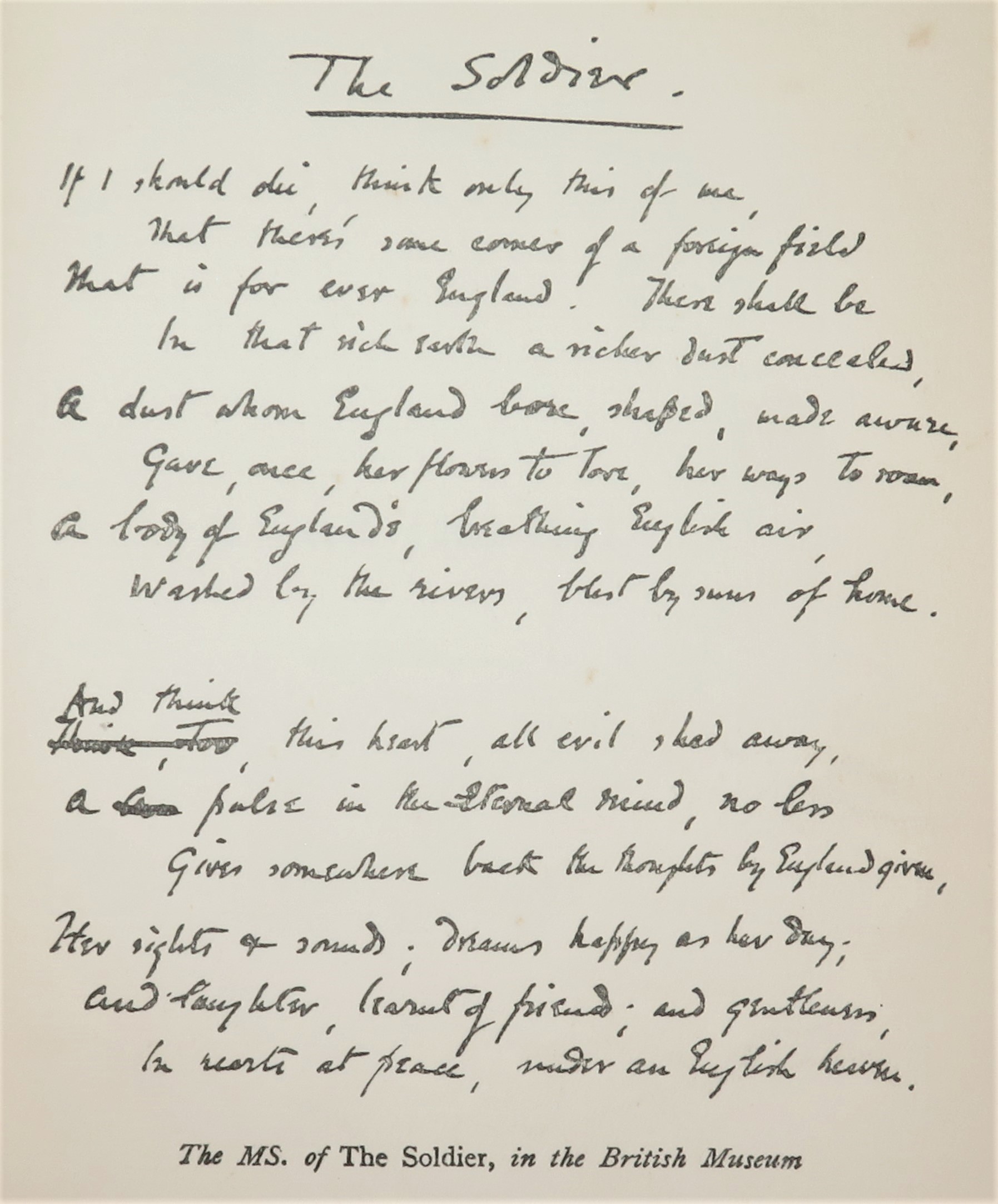

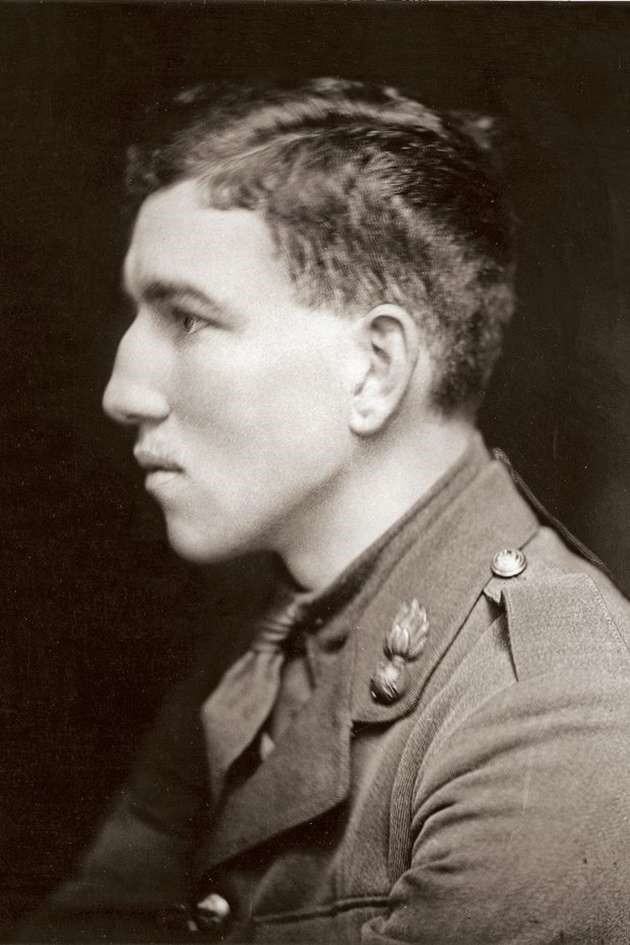

Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) rather makes the point. Among his most famous poems is “The Soldier”, published in early 1915, just a few months before his death, roughly half a year after the start of the First World War, and before the protracted horrors of the conflict tainted the poetic sensibilities and national sentiment of his poems.

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam;

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

As if to punctuate his poem, not long after it was published, Brooke died. His body was taken to the Greek island of Skyros, from whence Achilles had sailed for Troy, and buried in an olive grove.

In The Times, on 26 April 1915, Brooke was eulogized by Winston S. Churchill:

“Rupert Brooke is dead. A telegram from the Admiral at Lemnos tells us that this life has closed at the moment when it seemed to have reached its springtime. A voice had become audible, a note had been struck, more true, more thrilling, more able to do justice to the nobility of our youth in arms engaged in this present war, than any other more able to express their thoughts of self-surrender, and with a power to carry comfort to those who watch them so intently from afar. The voice has been swiftly stilled. Only the echoes and the memory remain; but they will linger.

During the last few months of his life, months of preparation in gallant comradeship and open air, the poet-soldier told with all the simple force of genius the sorrow of youth about to die, and the sure triumphant consolations of a sincere and valiant spirit. He expected to die: he was willing to die for the dear England whose beauty and majesty he knew: and he advanced towards the brink in perfect serenity, with absolute conviction of the rightness of his country’s cause and a heart devoid of hate for fellow-men.

The thoughts to which he gave expression in the very few incomparable war sonnets which he has left behind will be shared by many thousands of young men moving resolutely and blithely forward in this, the hardest, the cruelest, and the least-rewarded of all the wars that men have fought. They are a whole history and revelation of Rupert Brooke himself. Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, ruled by high undoubting purpose, he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in the days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable, and the most precious is that which is most freely proffered.”

Churchill’s was a lovely, panegyric eulogy, an evocation and echo of Brooke’s own poem, limning the poet’s death in the poet’s own sentimentality and glorification. But Brooke never saw front line action. He died of blood poisoning, presumably brought on by an insect bite to his lip. This may have been fortunate, as Brooke died en route to the charnel house of Gallipoli, where his Hood Battalion of the Royal Naval Division landed days later, and where nearly half a million Turkish and Allied troops became casualties.

The conspicuous romanticism of Brooke’s interment eclipses his undistinguished, unheroic ending – and provides a literary line of demarcation. Brooke’s ending, more than his burial, better symbolizes the bleak and bereft brutality of the First World War battlefields. Brooke’s poems proved an elegy to both himself and to his brand of poeticism, which, as the war progressed, gave way to a poeticism as mudded, bloodied, and bare of romance as the war’s trenches and No Man’s Land. Churchill, who would himself be serving on the Western Front by the end of 1915, had some inkling of the growing disillusions accompanying “this, the hardest, the cruelest, and the least-rewarded of all the wars that men have fought.” But Churchill did not know – could not yet know – the full literary measure of his opening statement “Rupert Brooke is dead.”

The death of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) came three and a half long years of war later and is a study in contrast. After stint at Craiglockhart War Hospital to treat shell-shock, Owen returned to the front. By the end of October, 1918, he found himself poised on the western side of the Sambre-Oise canal. Biographer Guy Cuthbertson relates how “Wilfrid Owen and his band of friends tried to cross the Canal. War veined the water with a dreadful red, before it all mingled to one tint.” (Cuthbertson, p.290) Owen was cut down by a German machine-gunner just a week before the Armistice.

While still convalescing at Craiglockhart, Owen had written verse of soldiering experience entirely unreconciled to Brooke’s “Soldier”. Fittingly, “Dulce et Decorum Este” was first published in the Hospital magazine, The Hydra, on 1 September 1917.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

“The War to End All Wars” did not. But it changed poetry. And it made – and unmade – poets. A scrappy pugilist, Robert Graves (1895-1985) reputedly earned the respect of his fellow soldiers and his first command through erudition with his fists, not his letters. After surviving the annihilation of his Royal Welch Fusiliers, he was transferred and met Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967). Graves’s senior by a decade, Sassoon’s pre-war poetry was highly romantic and imitative. “He was always ‘waiting for the spark from heaven to fall’, and when it fell it was shrapnel…” (ODNB)

Graves initially thought Sassoon too gung-ho about the war. Indeed, Sassoon, known as “Mad-Jack”, was awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous bravery and considered for the Victoria Cross. But he was anything but gung-ho when he chucked his MC ribbon into the River Mersey. And when Sassoon wrote a scathing anti-war declaration that was read in Parliament, his friend Graves lobbied for his hospitalization in lieu of a court martial. At Craiglockhart War Hospital Sassoon met a young poet named Wilfred Owen. While Owen published “Dulce et Decorum Este” in the Hospital’s literary magazine, which he edited, Sassoon contributed poems, including “Dreamers” and “Wirers”, that would later appear in his collections Counter-Attack and Other Poems and War Poems. Owen met Graves during the latter’s Hospital visits to Sassoon. Upon release, Sassoon was lucky to be once again merely wounded. His life and literary career, like that of Graves, would be long. Owen, like Brooke, suffered the bargain of Achilles – glory in lieu of longevity.

Theirs – Brooke, Owen, Graves, and Sassoon – were certainly not the only poetic voices shaping and shaped by the First World War. But these four encapsulate many of the agonies, contradictions, convolutions, and evolutions endured by the poets and poetry of the First World War. Together they span the war’s poetic preambles and its long, more knowing, less exulting and less lyrical aftermath.