Over the years, I’ve spilled a lot of proverbial ink writing and talking about books. Since I’m a bookseller, much of that is composition about books’ content or condition. But I’ve also been inclined to express – sometimes at length – a non-sectarian reverence for books. Books as physical objects that encapsulate intellect and insight, aesthetic and ambition, time and tide. Books for what they represent as much as for what they are. Sometimes I even indulge in reading books that share my reverence. And sometimes, as a writer, I’m forced to bow in deference to someone who expresses my thoughts better than I’ve expressed them myself.

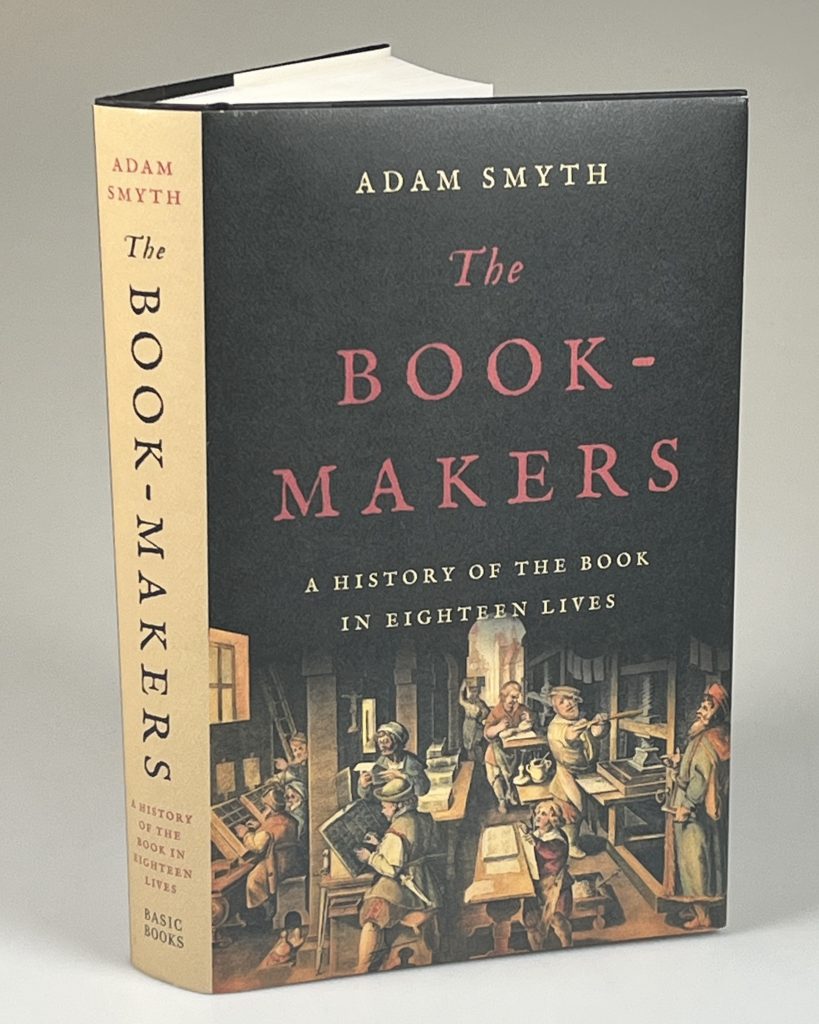

So it was when I was reading the Epilogue of a most unexpectedly excellent book called The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives by Adam Smyth (Basic Books, New York, 2024). With this post, my words are only intended to preface and present a few of his. A caveat: this is not a review of this compellingly interesting book. Rather, I’ll just share some of what I found in the last 17 pages.

So here goes.

On the subject of stewardship, rather than ownership of books, Symth speaks of “the poverty of singular claims to ownership: books move on, passing out of one owner’s clutches – however possessive those clutches might be – and moving on to meet the next generation. In this sense, the book always exceeds us, and the best we can do is feel it pass through our hands.”

On the book as an object that transcends the information it conveys, Smyth writes “Books are themselves incredible objects whose beauty and complexity enriches the text being read. Peer closely at calligrapher Edward Johnson’s curling green ‘W’ at the start of the Doves Press Hamlet, or the crystal-clear, immaculately spaced lettering of John Baskerville’s Paradise Lost. These are works of art that contribute to the meaning of the whole.”

On the connection between a book and its maker, between its present physical reality and the past from whence it came to us, Smyth writes “Books are expressive objects which themselves possess an emotional range and which convey, in their material forms, in ways that are sometimes legible, the texture of what it meant for a particular bookmaker to be alive.”

Of the future of the physical book, Smyth asserts “…this isn’t the end of anything – least of all the book – because a physical book is a different proposition to an electronic text. Print and digital need not be placed in an antagonistic relation to one another. The question ‘Will the book endure?’ or ‘Is the book dead?’ or ‘Will the internet kill the book?’ is mistaken because the five and a half centuries since Gutenberg show the book to be a form that has continually adapted to new people, ideas, contexts, and technologies, while all the time maintaining its identity as a physical support for text.”

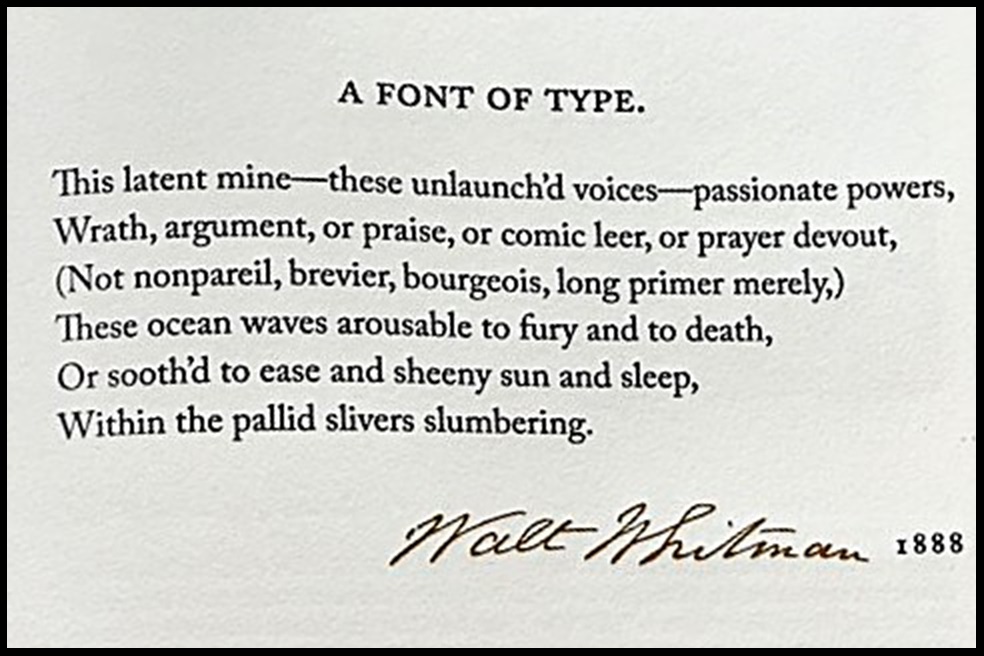

This is a lot of rarefied sentiment, to be sure. Smyth does not neglect the mechanical, technical, logistical, and even financial considerations of book-makers in his work, but he does beautifully interleave the practicalities and potentialities, exalting the latter all the better for comprehending the former. Perhaps the best example is the final paragraphs of his Epilogue, where Smyth quotes Whitman the poet writing lyrically as Whitman the book-maker. It turns out that “Whitman was a printer and a typesetter on Long Island, New York, long before his poetry collection Leaves of Grass…” Smythe quotes Whitman’s six-line poem “A Font of Type”. Smyth writes “Type, Whitman wrote elsewhere, ‘rejects nothing’. Type represents possibility… The tidy font of type – and we can widen the category of ‘type’ to include all the materials of book-making – is potentiality itself: a way of bringing as yet ‘unlaunch’d voices’ into the world.”

Yes, I recommend The Book. By which I mean all of them, Adam Smyth’s The Book-Makers included.

Cheers!