(or, more prosaically, on not judging a book by its cover)

My best lesson in not judging a book by its cover came from a bookseller, not a book.

I was exhibiting for the first time at an antiquarian bookfair. It was during setup, our books still strewn haphazardly in piles on tables and in boxes on the floor. It is customary for dealers to wander during setup, perusing the unfinished booths of colleagues in search of “finds” and securing them before the doors open to the public. But it is strictly and only dealers and their staff who are allowed in the fair hall during setup. So I was shocked and not a little angry to suddenly notice a drug-addled, hygienically challenged, sartorial horror of a person riffling my inventory.

Let me clarify my leap to this uncharitable characterization. The person in question was tall with a gaunt aspect. He moved in an oddly disjointed manner suggesting either narcotics or nerve damage. His clothes were an aesthetic affront on multiple counts – fashion, condition, and cleanliness. His shaggy mane of matted, black hair looked as if it had last (and not recently) been cut with garden shears and combed with a rake. Perhaps just before he was left outside in a hurricane. In the clothes he was still wearing. Glimpsed through the wooly thatch curtain partially obscuring his face were an impressively English collection of teeth, these giving the impression of ruined dice tossed into the man’s mouth by a vengeful deity.

I would have thrown him out of my booth. But a friend and colleague with whom I was sharing the booth put her hand on my arm and said “Wait.” I heeded.

In less than a minute, the man peremptorily announced to me “Right, I’ll take these”. The “these” were an assortment of $ four figure books, arguably the most interesting among the carefully curated items I had brought to the fair. I was gobsmacked at the literary scope, commercial acumen, and improbable speed of his discernment. The business card he dropped on his selected pile was that of one of the world’s foremost booksellers. The man’s employer was obviously able to see past the proverbial binding, even if I was not.

Most of us don’t get to profit handsomely from lessons in humility. I was fortunate in the gift of my wiser colleague’s staying hand on my arm. This allowed time for my own discernment to overcome my crude, cursory, and condescending assumptions.

In the years since, I have learned to apply a more patient regard to books – as well as to the eclectic, eccentric, and often unkempt savants who sell them.

Like all of us, I love a pretty book. I’m a sucker for immaculate old dust jackets, tastefully decorated publisher’s cloth, and, of course, a true craftsman’s fine leather binding. But I’ve learned to leave room in my heart and on my shelves for the beautifully ruined.

So how about Volume V of the Albany Edition of The Works of Lord Macaulay? Is that one you covet for your shelves? What if I told you it was badly worn, with the sewn text block unraveling, splits on the front and rear endpapers, and the spine separated along the front cover, which remains attached only by a thin strip of cloth?

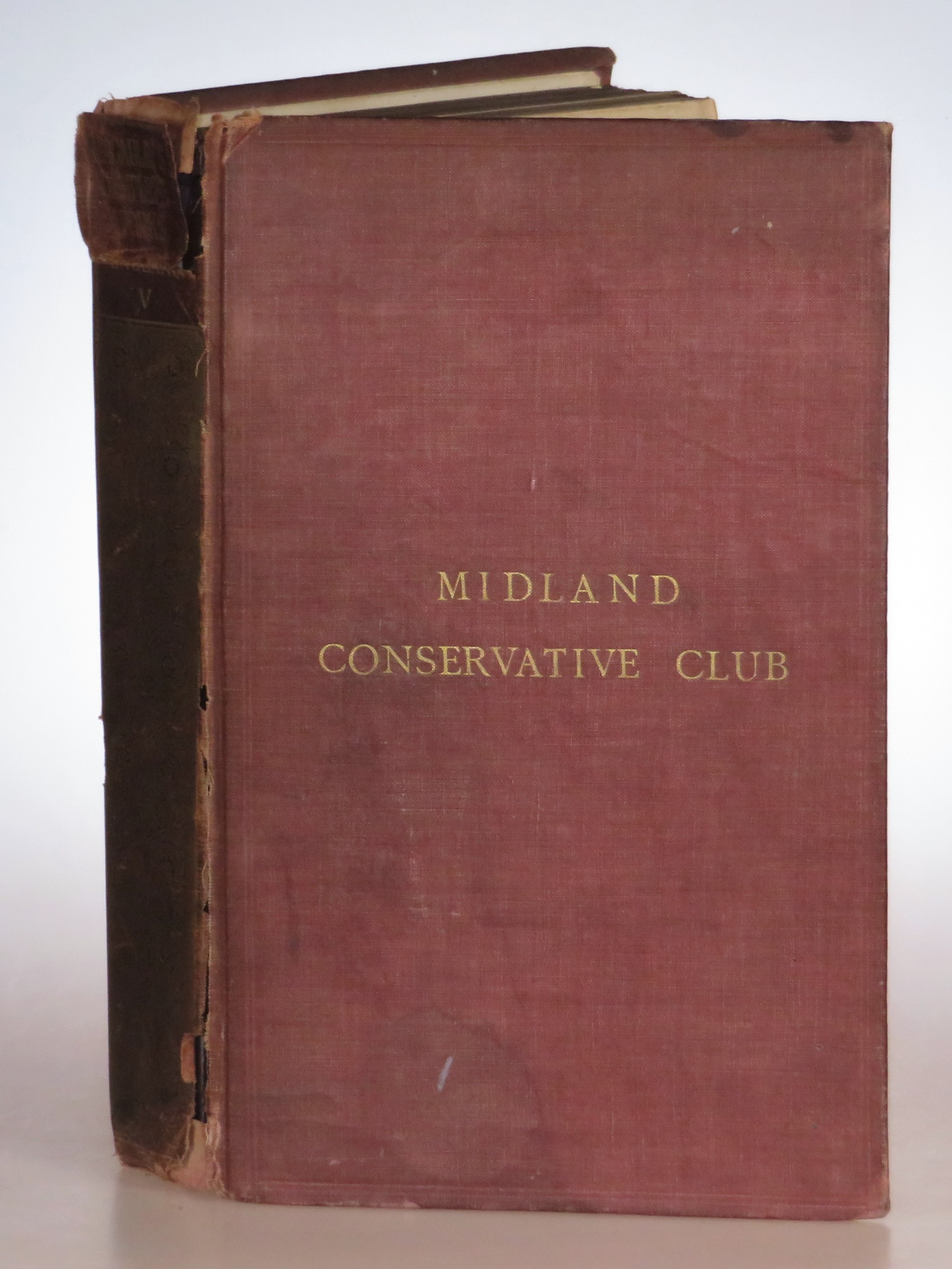

OK. A few more details. This is the work Winston S. Churchill would refute three decades later with his own four-volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough. And this particular volume was presented to the Midland Conservative Club in 1900 by its twenty-four-year-old President… Winston S. Churchill. Affixed to the front pastedown of this tattered volume was a plate reading “PRESENTED | TO THE | MIDLAND CONSERVATIVE CLUB | BY | WINSTON S. CHURCHILL, ESQ. | PRESIDENT | 1900”.

1899 saw both Churchill’s first, unsuccessful run for parliament as a Conservative candidate for Oldham and his appointment as president of the Midland Conservative Club. Churchill remained club president until 1901, by which time he had become a member of Parliament. While president of the Midland Conservative Club Churchill launched a political career that lasted two thirds of a century, saw him occupy a cabinet office during each of the first six decades of the twentieth century, and carried him twice to the premiership and into the annals of history as a preeminent statesman.

But first there was Macaulay. Perhaps no historian exceeded the impact of Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) on Churchill’s literary life. Churchill’s own history with Lord Macaulay dated to schoolboy days at Harrow where he received a prize for reciting from memory 1200 lines of Macaulay’s “Lays of Ancient Rome”. While a cavalry officer in India, Churchill devoured Macaulay’s History of England, including lengthy treatment of Churchill’s great ancestor, John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough. Macaulay’s writing influenced Churchill’s own, with its “captivating style and devastating self-confidence”. This Volume V of Macaulay’s works contains the author’s generally negative treatment of Marlborough.

Decades later, Macaulay would prove a literary catalyst for Churchill, who eventually came to regard Macaulay as a “prince of literary rogues, who always preferred the tale to the truth”. The most substantial work of Churchill’s “wilderness years” of the 1930s – Marlborough: His Life and Times – was conceived in part as a refutation of Macaulay’s history. Churchill spent 10 years researching and writing his four-volume biography with the express intent to “fasten the label ‘Liar’ to [Macaulay’s] genteel coat-tails.” More than half a century after he presented this book, when Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953, it was partly for “mastery of historical and biographical description” on the strength of Marlborough, which was specifically cited and quoted by the Swedish Academy.

We once offered a first edition, first printing, first state of Churchill’s first published book The Story of the Malakand Field Force – signed by Churchill during his first North American lecture tour. The binding remained beautifully bright, as did the contents. It was not only incredibly well-preserved, but clearly unequivocally unread, as all of the signatures remained uncut. Of course I’d want it for my shelves. But I’d not hesitate to put Volume V of the Albany Edition of The Works of Lord Macaulay on the shelf beside it.

In our quest for the perfect copy, it is easy to forget that the existential purpose of a book is to be read. As collectors, we may favor the few pristine copies that have eluded their fate, but there should be a place on our shelves for books roughened by the regard of previous readers. Such books tangibly witness the time, places, and experiences through which they traveled to us, not just neatly presenting history in tidy print, but accreting history in a mélange of scuffs, stains, and scribbles.

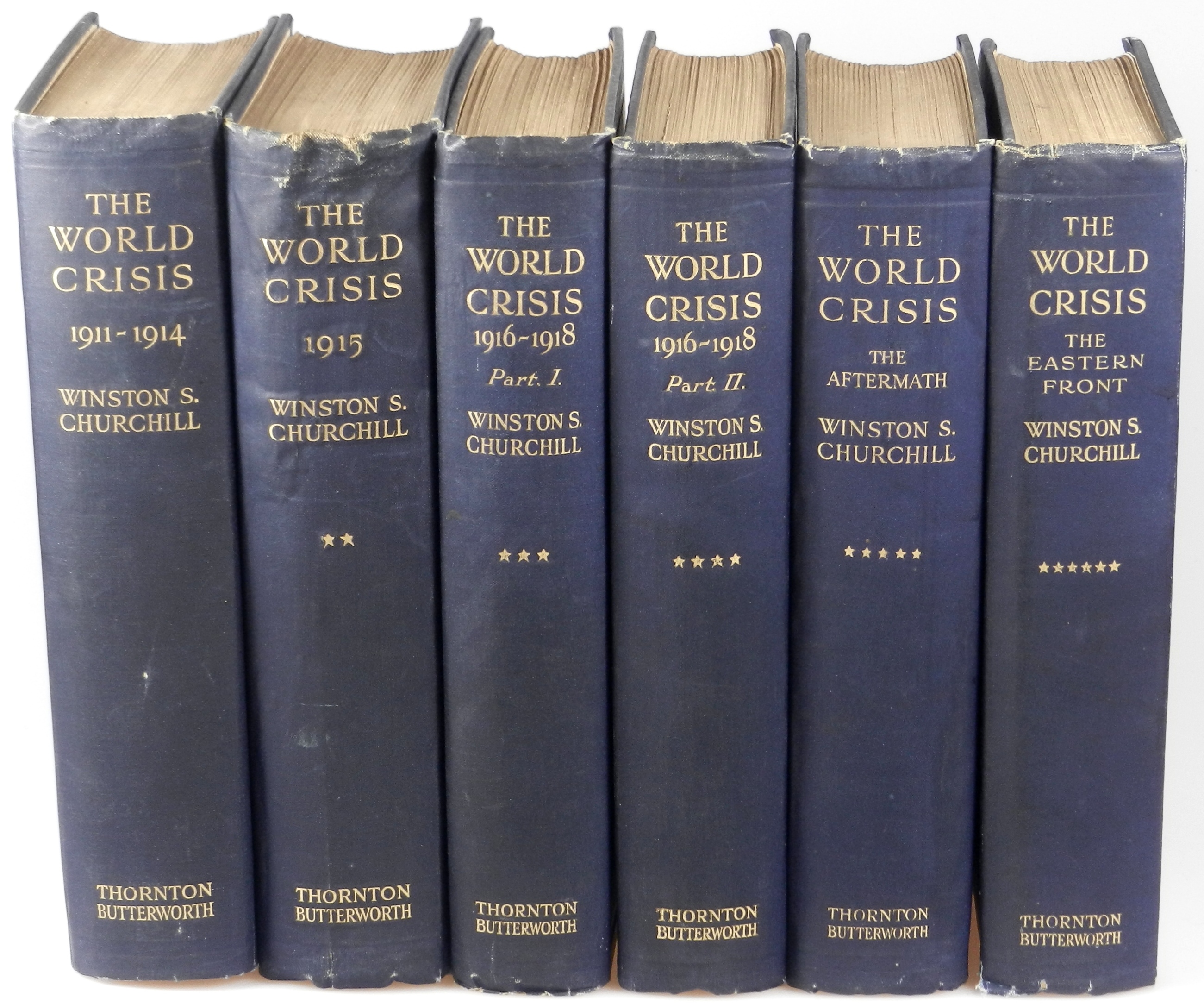

I own a lovely, jacketed, British first edition, first printing, six-volume set of Churchill’s history of the First World War, The World Crisis. But I still debate whether I should replace it on my shelves with an unjacketed, mixed printing set – a set not only worn, but full of writing in several hands. It is not a set that a fastidious collector would regard – unless they opened the covers.

THIS is the set to which I refer. Like a certain bookseller I once met, the set is quite magnificent in its unloveliness.

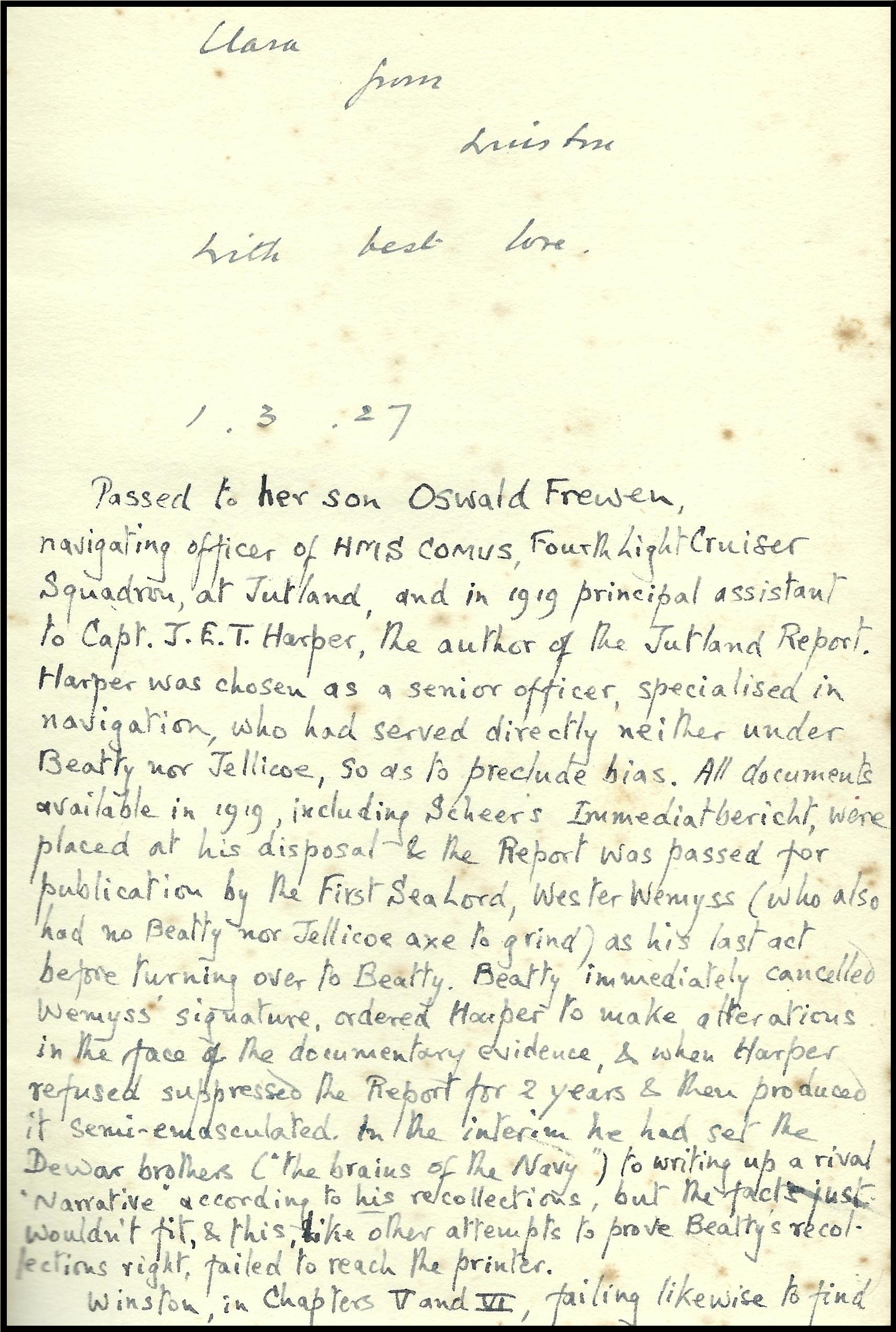

This set has five dated inscriptions from Churchill to his Aunt and significant annotations by her son, Churchill’s first cousin. The worn condition owes to this cousin, who freely admitted “I am one of those horrible readers who deface their books with marginal comments…”

Normally I’d wince. But in this case the “defacer”, Captain Oswald Moreton Frewen (1887-1958), was a career naval officer who served under Churchill during his tenure as First Lord of the Admiralty in both the First and Second World Wars. Oswald participated in every naval engagement in the North Sea during the First World War, after the war helped the Admiralty prepare the official history of the Battle of Jutland, and during the Second World War served as King’s Harbour Master of Scapa Flow. Oswald’s extensive annotations in this set run to thousands of words. These annotations are remarkably informed and informative, sharply critical, compellingly interesting, and sometimes quite personal about his cousin, the author.

This set is indelibly and uniquely endowed with a history beyond that which was printed therein. We may forgive that this came at the expense of condition.

A final story, less rarified but to the point. Years ago we acquired a horribly tatty, poorly rebound first edition of My African Journey as part of an auction lot. No punchline here I’m afraid; there was nothing between the covers but worse-for-wear first edition contents. On a whim, I took the book with me when I traveled to Africa, where I read it. I spent my last night in Africa in a tented camp in the Serengeti. It is a semi-permanent camp, almost Victorian in the comparative luxury it affords in the middle of such a remote and unspoiled place. In the camp’s main tent was a small library with a selection of books about Africa. Right before we departed, I secretly left Winston’s book there on the shelf. I hope is has been read again, even unto pieces.

Cheers!

One thought on “The Beautifully Ruined”