In a 2013 interview by the Churchill Centre I was asked: “What story from your experience dealing in Churchill books stays with you?” I replied: “What intrigues me most these days are the speculative fractions of a story that emerge from some of the objects we handle. The story I don’t fully know…”

We had the opportunity to catalogue just such an item recently – an item that intrigues me as much for what I will never know about it as for what I do know.

We had the opportunity to catalogue just such an item recently – an item that intrigues me as much for what I will never know about it as for what I do know.

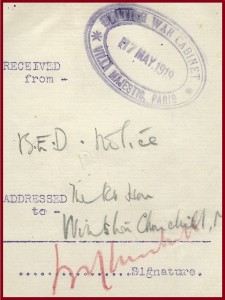

This compelling little piece of history is a British War Cabinet Document Receipt from the Villa Majestic, Paris, signed by Winston Churchill on 17 May 1919 during the Paris Peace Conference.

The receipt measures roughly 5 x 4 inches, printed and stamped in purple ink on plain white stock, with autograph in both pencil and red. The words “RECEIVED from –“ and “ADDRESSED to –“ as well as a line for “Signature” are printed in purple and the upper right corner bears the oval stamp, also in purple, of the “BRITISH WAR CABINET * VILLA MAJESTIC, PARIS *” date stamped “17 MAY 1919”. In pencil below “RECEIVED from –“ is “B.E.D. Notice” (“B.E.D.” being the abbreviation for “British Empire Delegation”). In pencil beside and below “ADDRESSED to –” is “The Rt Hon Winston Churchill, M.P.” On the signature line, in red, Churchill signed “WS CHURCHILL”.

The receipt measures roughly 5 x 4 inches, printed and stamped in purple ink on plain white stock, with autograph in both pencil and red. The words “RECEIVED from –“ and “ADDRESSED to –“ as well as a line for “Signature” are printed in purple and the upper right corner bears the oval stamp, also in purple, of the “BRITISH WAR CABINET * VILLA MAJESTIC, PARIS *” date stamped “17 MAY 1919”. In pencil below “RECEIVED from –“ is “B.E.D. Notice” (“B.E.D.” being the abbreviation for “British Empire Delegation”). In pencil beside and below “ADDRESSED to –” is “The Rt Hon Winston Churchill, M.P.” On the signature line, in red, Churchill signed “WS CHURCHILL”.

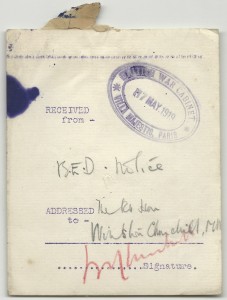

Tantalizingly, the receipt’s upper blank verso retains a fragment of the document to which it was ostensibly affixed as a receipt.

Tantalizingly, the receipt’s upper blank verso retains a fragment of the document to which it was ostensibly affixed as a receipt.

During the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the British government delegation resided at the Hotel Majestic. In May 1919 Churchill was serving as Secretary of State for War and Air. Only in his mid-40s and still two decades away from becoming Prime Minister, he was nonetheless already a polarizing national figure who had held several important Cabinet positions and been a political force since the turn of the century. In the First World War, Churchill remarkably served both in the Cabinet and at the front, nearly losing his political life in the former and his corporeal life at the latter. Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1911 until 1915, but was scapegoated for the Dardanelles tragedy and the slaughter at Gallipoli and forced to resign. He would spend part of his political exile as a lieutenant colonel leading a battalion in the trenches.

By the war’s end, he was exonerated and rejoined the Government, initially as Minister of Munitions. In January 1919, Churchill became Secretary of State for War and Air – the same month that the Paris Peace Conference convened. On 17 May 1919, Churchill arrived in Paris at 2:00 am. His meetings in Paris that day included Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson (Chief of the Imperial General Staff), Lord Alfred Milner (Secretary of State for the Colonies), Edwin Samuel Montagu (Secretary of State for India), General Maharaja Sir Ganga Singh, and Edward George Villiers Stanley (Lord Derby, British Ambassador to France). Issues commanding his attention ranged from occupation of Jellalabad, to who would be British Military Attache in Paris, to his exhaustive efforts to secure support for anti-Bolshevik factions in Russia.

We do have a snapshot of Churchill’s disposition on the day, which might be aptly characterized as quintessentially Churchillian; Winston was described on 17 May 1919 by Sir Henry Wilson as being both “in good form” and “very mulish.” (Diary of Sir Henry Wilson, Gilbert, CV IV, Part I, p.654)

Churchill is standing in the front row, third to the right of David Lloyd George. Sir Henry Wilson is immediately behind and to the right of Churchill.

Churchill expressed profound – and ultimately prophetic – reservations about harshly punitive terms in the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on 28 June 1919, six weeks after Churchill signed this receipt. On 7 July 1921, Churchill would tell the Imperial Conference in London: “The aim is to get an appeasement of the fearful hatreds and antagonisms which exist in Europe…” Advocating a policy of reconciliation, Churchill wanted Britain to be both “the ally of France and the friend of Germany” to mitigate “the frightful rancour and fear and hatred” between France and Germany which he warned “if left unchecked, will most certainly in a generation or so bring about a renewal of the struggle of which we have just witnessed the conclusion.”

Churchill’s argument did not prevail. The triumphant army of a bitterly resurgent Germany would set up its headquarters in the ex-Hotel Majestic after France’s conquest in June 1940, a month after Churchill became wartime Prime Minister. The fascinating historical irony lends poignance to this humble receipt.

This item comes to us from the collection of former British book collector and book seller David B. Mayou, known for his knowledge and collection of Churchill material. Churchill’s biography literally sets a world record for length and comprehensiveness. The man led a conspicuously public life and most stories – from famous quips to great events – are already known and exhaustively discussed. Mayou’s passing without imparting any further information he may have known about this receipt means that – along with the glue and document fragment – a little mystery adheres to this receipt and it can continue to intrigue us, for which I’m strangely grateful.