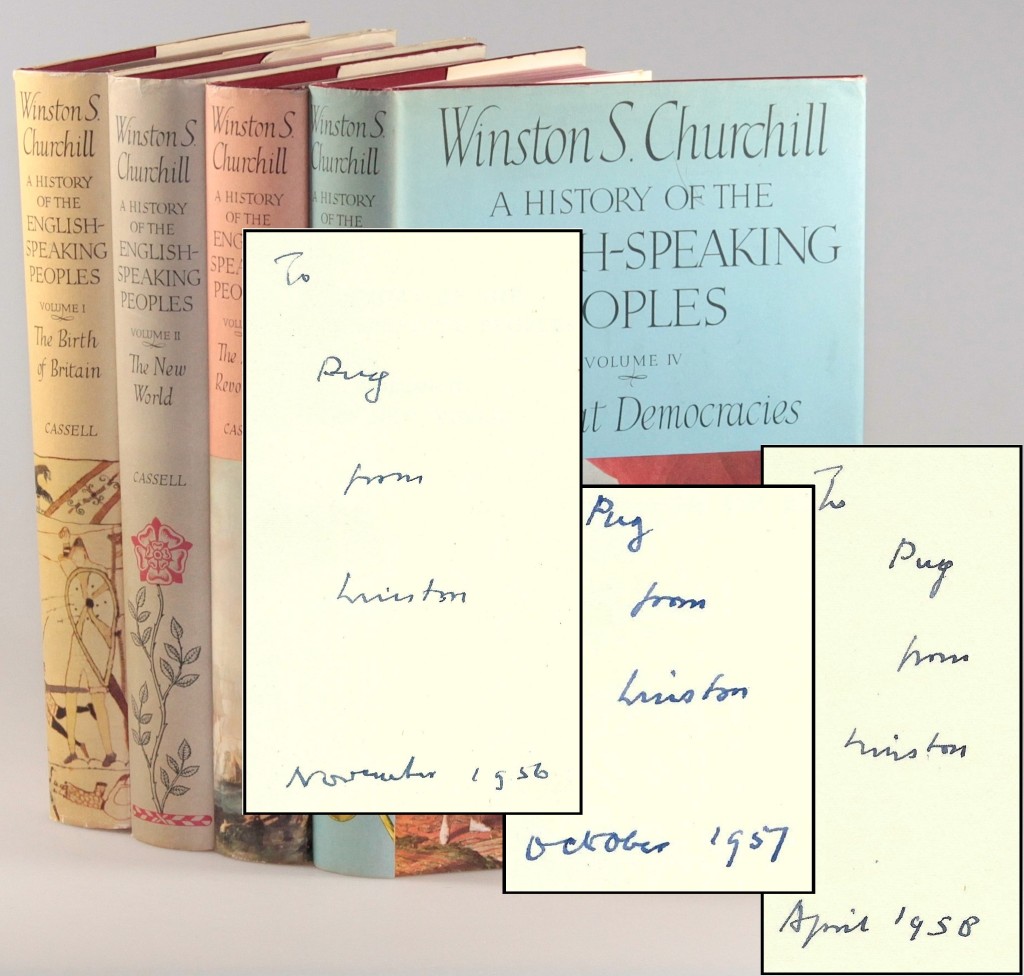

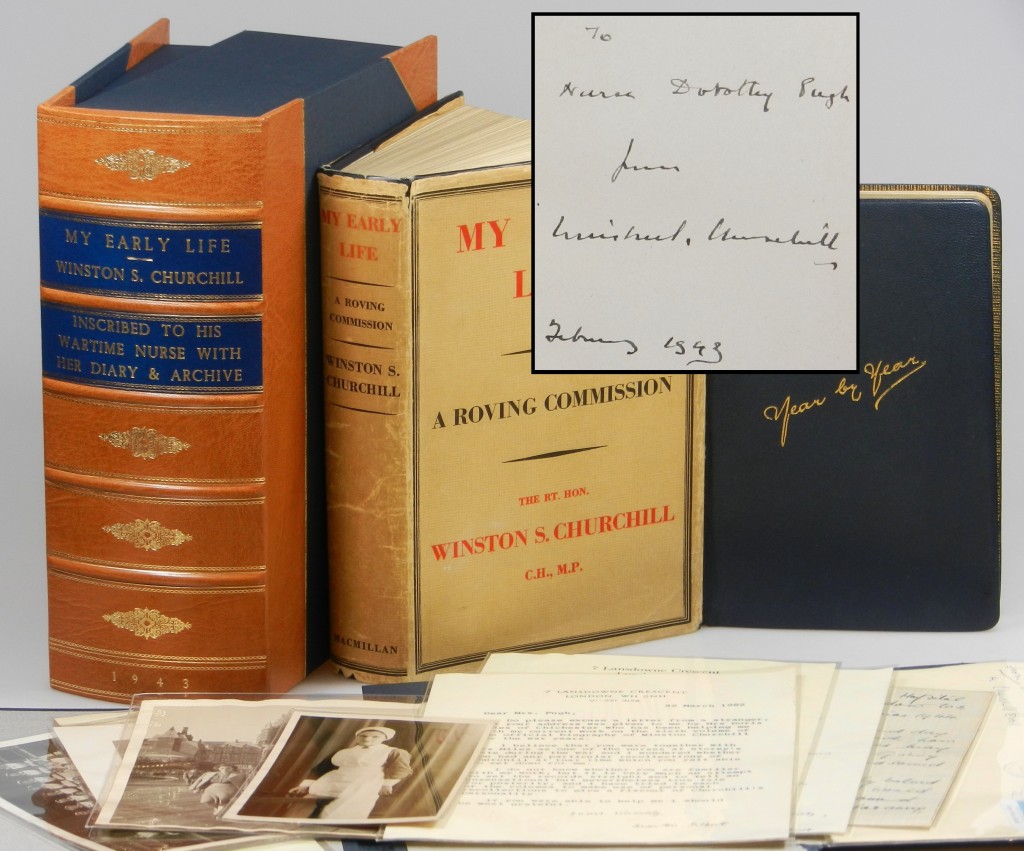

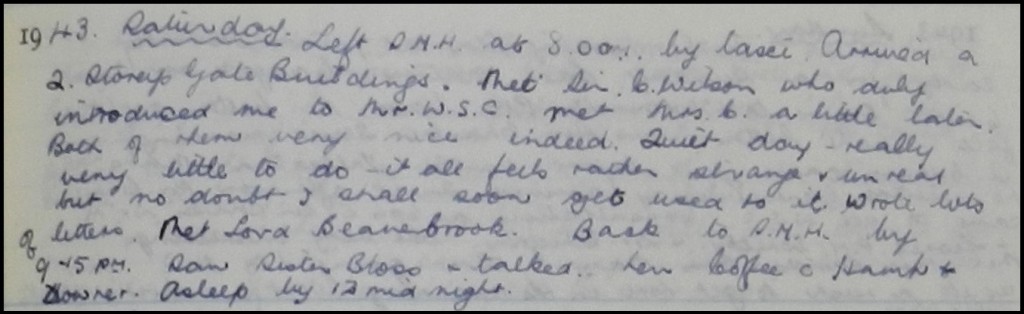

We recently had the privilege of cataloguing a remarkable, inscribed first edition set of Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Only one collector will have the good fortune of being this set’s next owner, but it is compelling enough to merit sharing with a wider audience. Hence this post.

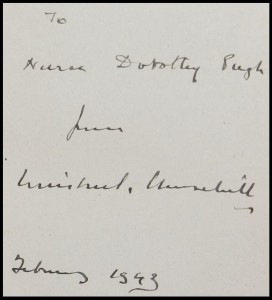

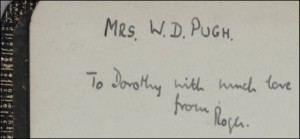

This set is inscribed and dated in three volumes to Churchill’s close friend and indispensable wartime Chief of Staff, General Lord Hastings Lionel “Pug” Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (1887-1965). Each of the three volumes is intimately inscribed using Ismay’s nickname and Churchill’s first name.

This set is inscribed and dated in three volumes to Churchill’s close friend and indispensable wartime Chief of Staff, General Lord Hastings Lionel “Pug” Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (1887-1965). Each of the three volumes is intimately inscribed using Ismay’s nickname and Churchill’s first name.

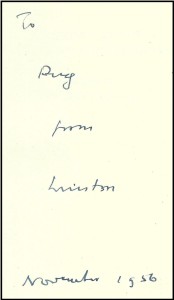

Volume II is inscribed in five lines in black ink: “To | Pug | from | Winston | November 1956”.

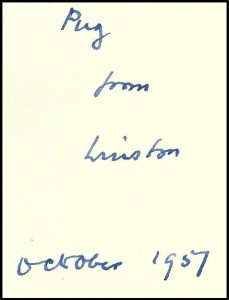

Volume III is inscribed in four lines in blue ink: “Pug | from | Winston | October 1957”.

Volume III is inscribed in four lines in blue ink: “Pug | from | Winston | October 1957”.

Volume IV is inscribed in five lines in black ink: “To | Pug | from | Winston | April 1958”.

Volume IV is inscribed in five lines in black ink: “To | Pug | from | Winston | April 1958”.

The Association

We became hand in glove and much more…”

(Churchill, The Gathering Storm, 1948)

This was Churchill’s own and ultimate tribute to his friend.

When Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940, he also assumed appointment as Minister of Defence. Ismay served as Churchill’s Chief of Staff in that capacity and others, for Churchill’s entire wartime premiership. During the war, Ismay also served as Deputy Secretary to the War Cabinet. Ismay described his role thus: “I had three sets of responsibilities. I was Chief of Staff Officer to Mr. Churchill; I was a member of the Chiefs of Staff Committee; and I was head of the Office of the Minister of Defence. Thus I was a cog which had to operate in three separate though intimately connected mechanisms.” Less formally, Ismay summarized: “I had a legitimate foot in every camp – naval, military, air, as well as political. I did not have a finger in every pie, but it was my duty to know about all the pies that were being cooked and how they were getting on.” (Ismay, Memoirs, p.168)

When Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940, he also assumed appointment as Minister of Defence. Ismay served as Churchill’s Chief of Staff in that capacity and others, for Churchill’s entire wartime premiership. During the war, Ismay also served as Deputy Secretary to the War Cabinet. Ismay described his role thus: “I had three sets of responsibilities. I was Chief of Staff Officer to Mr. Churchill; I was a member of the Chiefs of Staff Committee; and I was head of the Office of the Minister of Defence. Thus I was a cog which had to operate in three separate though intimately connected mechanisms.” Less formally, Ismay summarized: “I had a legitimate foot in every camp – naval, military, air, as well as political. I did not have a finger in every pie, but it was my duty to know about all the pies that were being cooked and how they were getting on.” (Ismay, Memoirs, p.168)

Ismay’s position was unique, both in the confidence he enjoyed and the scope and duration of his service. “Hundreds of Churchill’s famous minutes and the replies to them were personally handled by Ismay, who commanded the prime minister’s absolute trust. He was the essential link with the chiefs of staff… Difficult allies respected him as much as did difficult colleagues. On delicate missions abroad, amid growing responsibilities for the most secret matters, from 1940 to 1945 Ismay endured strains more continuous than any battle-commander, and sometimes equally intense. Not even Sir Alan Brooke was so exposed to the exigencies and exhaustion of intimate work with Churchill by day and by night.” Ismay was “Shrewd, resilient, accessible, emollient in diplomacy but of an unbreachable integrity.” (ODNB)

Ismay’s position was unique, both in the confidence he enjoyed and the scope and duration of his service. “Hundreds of Churchill’s famous minutes and the replies to them were personally handled by Ismay, who commanded the prime minister’s absolute trust. He was the essential link with the chiefs of staff… Difficult allies respected him as much as did difficult colleagues. On delicate missions abroad, amid growing responsibilities for the most secret matters, from 1940 to 1945 Ismay endured strains more continuous than any battle-commander, and sometimes equally intense. Not even Sir Alan Brooke was so exposed to the exigencies and exhaustion of intimate work with Churchill by day and by night.” Ismay was “Shrewd, resilient, accessible, emollient in diplomacy but of an unbreachable integrity.” (ODNB)

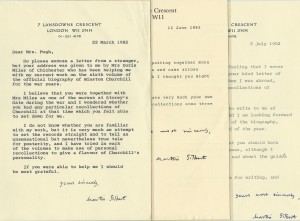

When Churchill’s second premiership began in October 1951, Ismay was first appointed Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations and, swiftly thereafter, Secretary-General of NATO, a post he held from 1952 until his retirement in 1957.

Even Ismay’s early career was deeply shaped by his future Prime Minister and patron. As a young officer in India in 1910 “Mr. Winston Churchill, whom I had never met, and, as it then seemed, was unlikely ever to meet, exercised a decisive influence on my future.” Despite shock that “anyone who had started so brilliantly should have thrown it all up and gone into Parliament” Ismay was critically inspired by Churchill’s intrepid early accomplishments with both sword and pen. Ismay felt “on the whole, I could not do better than try to emulate the example of his early years” and resolved to apply himself diligently to both active service opportunities and self-education. This included close reading of Churchill’s The River War (which he would argumentatively quote to Churchill more than three decades later). (Ismay, Memoirs, pp.15-16)

Like Churchill, Ismay was educated at Sandhurst and saw early service as a cavalry officer in India. Unlike Churchill, Ismay did not leave soldiering for politics. By the early 1920s, recognition of his talents and his performance at the Staff College in Quetta ended Ismay’s regimental soldiering. Ismay would serve the Committee of Imperial Defence in various capacities, becoming CID Deputy Secretary in 1936 and Secretary in 1938, and being promoted major-general in 1939. “Inadequacies of government policy made the months before and immediately after the outbreak of war in 1939 the most frustrating of his life.” (ODNB) But in April 1940, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain chose Ismay to assist Churchill in his role as chairman of the ministerial co-ordinating committee. A month later Churchill became Prime Minister. Ismay would be promoted Lieutenant-General in 1942 and General in 1944, and made Baron in 1947.

Both their close bond and Churchill’s reliance upon Ismay endured after Churchill’s wartime premiership. When Churchill wrote his six volume war memoirs, Ismay was his principal advisor on all military questions. (Gilbert, VIII, p.221) “With Ismay as a guide, Churchill knew that he could be certain of a careful, accurate scrutiny of his work, and the bringing in wherever necessary of other experts and helpers.” (Gilbert, VIII, p.235) Ismay proved as indispensable in this as he had in the war, providing a steady stream of substantive notes and documents, edits and amendments, recollections, and perspective. Bill Deaken later recalled “Ismay read everything on the military side. He was frequently a guest at Chartwell and at Hyde Park Gate. He loved Winston with a passion. Winston relied on his judgement. He had no military confidant except Ismay.” Gilbert, VIII, p.315)

One anecdote among many testifies to the depth of a personal relationship that underpinned and transcended shared service: Within hours of becoming Prime Minister for the second and final time on 26 October 1951, Churchill phoned Ismay, rousing him from sleep: “Is that you, Pug?” “Yes, Prime Minister. It’s grand to be able to call you Prime Minister again.” “I want to see you at once. You aren’t in bed, are you?” Ismay recalled “I put my head under a cold tap, dressed in record time, and was at 28, Hyde Park Gate within a quarter of an hour of being wakened… I was overjoyed at the prospect of serving under Churchill again.” (Ismay, Memoirs, pp.452-453)

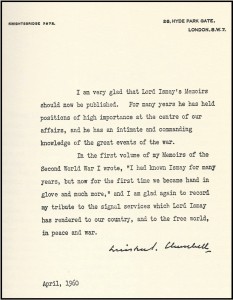

When Churchill inscribed these books to Ismay, both men were entering their twilight, both adding final words to a lifetime of deeds. Two years after Churchill inscribed his final volume of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples to “Pug,” Ismay’s own Memoirs were published, opening with a Tribute from Churchill “to the signal services which Lord Ismay has rendered to our country, and to the free world, in peace and war. Churchill was the guest of honor at a London dinner to celebrate the publication of Ismay’s Memoirs. (Gilbert, VIII, p.1315) Both men died in 1965.

When Churchill inscribed these books to Ismay, both men were entering their twilight, both adding final words to a lifetime of deeds. Two years after Churchill inscribed his final volume of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples to “Pug,” Ismay’s own Memoirs were published, opening with a Tribute from Churchill “to the signal services which Lord Ismay has rendered to our country, and to the free world, in peace and war. Churchill was the guest of honor at a London dinner to celebrate the publication of Ismay’s Memoirs. (Gilbert, VIII, p.1315) Both men died in 1965.

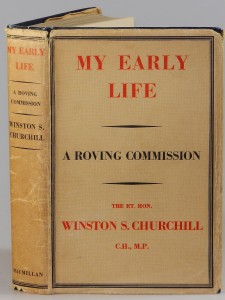

The Edition

A History of the English-Speaking Peoples is Churchill’s sweeping history and last great work. The first draft was completed just before the Second World War, but the work was not completed and published until after Churchill’s second and final Premiership, nearly 20 years later. The work traces a great historical arc from Roman Britain through the end of the Nineteenth Century, ending with the death of Queen Victoria. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is the very year that saw Churchill conclude his first North American lecture tour, take his first seat in Parliament, and begin to make history himself.

The first British edition is regarded as one of the most beautiful productions of Churchill’s works, with tall red volumes and striking, illustrated dust jackets. Churchill seems to have taken an active and detailed interest in the aesthetics of the publication. He told his doctor: “it is not necessary to break the back of the book to keep it open. I made them take away a quarter of an inch from the outer margins of the two pages and then add the half-inch so gained to the inner margin.” He was clearly satisfied with the result, remarking with pardonable exuberance “It opens like an angel’s wings.” (Gilbert, Volume VIII, p.1184) Unfortunately, as beautiful as the first editions are, they proved somewhat fragile. The dust jackets commonly suffer significant fading, wear, soiling, and spotting, and the books typically bear spotting and fading of the red-stained top edges.

To read more about the first edition of Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples in our online Guide to Churchill’s Books, click HERE.

In recent years, several items inscribed by Churchill to Lord Ismay have been offered, but few as first edition sets in original bindings. The inscriptions would make this set special even if it were rebound and later printing, but the fact that it is first printings in original bindings makes it especially compelling.

This set is currently offered for sale HERE.

Cheers!