We are pleased to have recently discovered 1942 limited and numbered edition of The Atlantic Charter. This is the only copy we have encountered of this edition and is a certifiable NIC.

NIC?

That’s short for “Not in Cohen”.

Nearly 25 years of exhaustive research went into Ronald I. Cohen’s indispensable three-volume, 2,183 page Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. No less an authority than Sir Martin Gilbert effusively praised Ron’s work, calling it: “…a high point – and surely a peak – of Churchill bibliographic research… adding not only to the bibliographer’s art, but to knowledge of Winston Churchill himself.” Published in 2006, Ron’s Bibliography seeks to detail every single edition, issue, state, printing, and variant of every printed work authored by, or with a contribution from, Winston S. Churchill. Take it from a professional bookseller – even in the characteristically thorough world of bibliographies, Ron’s stands out. So the rare occasions when we discover a work by Churchill unknown to Ron – an NIC – it is cause for pardonable bit of bibliophilic fanfare.

Nearly 25 years of exhaustive research went into Ronald I. Cohen’s indispensable three-volume, 2,183 page Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. No less an authority than Sir Martin Gilbert effusively praised Ron’s work, calling it: “…a high point – and surely a peak – of Churchill bibliographic research… adding not only to the bibliographer’s art, but to knowledge of Winston Churchill himself.” Published in 2006, Ron’s Bibliography seeks to detail every single edition, issue, state, printing, and variant of every printed work authored by, or with a contribution from, Winston S. Churchill. Take it from a professional bookseller – even in the characteristically thorough world of bibliographies, Ron’s stands out. So the rare occasions when we discover a work by Churchill unknown to Ron – an NIC – it is cause for pardonable bit of bibliophilic fanfare.

Hence our excitement about this edition of the Atlantic Charter.

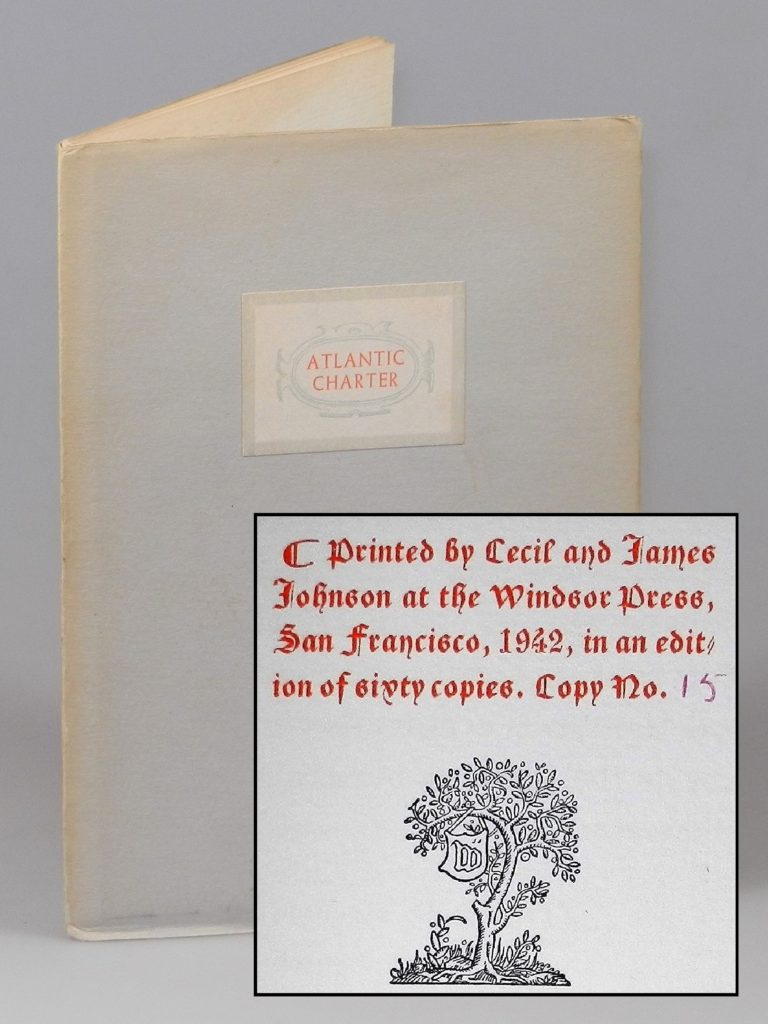

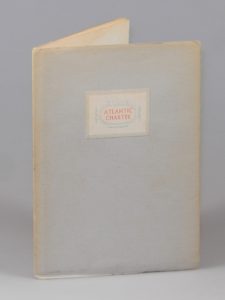

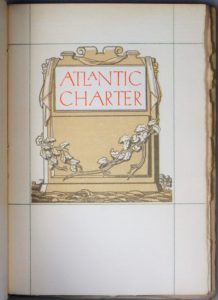

This diminutive but quite attractive book measures 7 x 5 inches, bound in dove gray paper covered card boards with a white front cover title label printed gray and red, the gray paper affixed by flaps secured beneath the pastedowns. The contents are printed in black and red on watermarked, laid paper with untrimmed edges. Eight pages reproduce the eight points of the Atlantic Charter, followed by an illustrated limitation page and preceded by an illustrated title page. The limitation page reads: “Printed by Cecil and James | Johnson at the Windsor Press, | San Francisco, 1942, in edit | ion of sixty copies. Copy No. 15”. The limitation is hand-numbered in red ink.

The Windsor Press was established in San Francisco in 1924 by the Australian brothers, James and Cecil Johnson, with James as designer, typographer, and pressman and Cecil as manager.

The beautiful, limited edition was quite plausibly printed for the first anniversary of the Atlantic Charter in 1942, which President Roosevelt marked with a 14 August 1942 message to Churchill reaffirming commitment to the principles of the Atlantic Charter.

In August 1941, Winston Churchill had braved the North Atlantic seas during the Battle of the Atlantic to voyage by warship to Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, where he met President Franklin D. Roosevelt for a remarkable secret conference from the 9th to the 12th. Part of their agenda included an effort to set constructive goals for the post-war world, even as the struggle against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was still very much undecided and the U.S. had yet to formally enter the war. The eight principles to which they agreed became known as the Atlantic Charter.

In August 1941, Winston Churchill had braved the North Atlantic seas during the Battle of the Atlantic to voyage by warship to Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, where he met President Franklin D. Roosevelt for a remarkable secret conference from the 9th to the 12th. Part of their agenda included an effort to set constructive goals for the post-war world, even as the struggle against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was still very much undecided and the U.S. had yet to formally enter the war. The eight principles to which they agreed became known as the Atlantic Charter.

ATLANTIC CONFERENCE BETWEEN PRIME MINISTER WINSTON CHURCHILL AND PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D ROOSEVELT 10 AUGUST 1941 The President of the United States and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom are seated on the Quarterdeck of HMS PRINCE OF WALES for a Sunday service, during the Atlantic Conference, 10 August 1941. In the row behind them, left to right: Air Chief Marshal Sir Wilfred Freeman; Admiral E J King; USN; General Marshall; General Sir John Dill; Admiral Stark, USN; Admiral Sir Dudley Pound.

“That it had little legal validity did not detract from its value… Coming from the two great democratic leaders of the day… the Atlantic Charter created a profound impression on the embattled Allies. It came as a message of hope to the occupied countries, and it held out the promise of a world organization based on the enduring verities of international morality.” (United Nations)

In addition to encapsulating the postwar aspirations of the Allies and catalyzing formation of the United Nations, the Atlantic Charter also testifies to perhaps the most remarkable personal relationship of the Second World War, that between Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

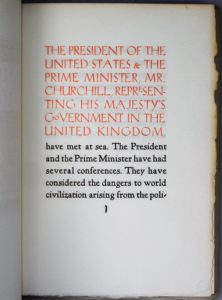

The President of the United States and the Prime Minister, Mr. Churchill, representing H. M. Government in the United Kingdom, being met together, deem it right to make known certain common principles in the national policies of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.

President Roosevelt welcomes Prime Minister Churchill aboard the USS Augusta for the Atlantic Conference, August 1941

- Their countries seek no aggrandisement, territorial or other.

- They desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned.

- They respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of Government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.

- They will endeavour with due respect for their existing obligations, to further enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.

- They desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field, with the object of securing for all improved labour standards, economic advancement, and social security.

- After the final destruction of Nazi tyranny, they hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.

- Such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance.

- They believe all of the nations of the world, for realistic as well spiritual reasons, must come to the abandonment of the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea, or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential. They will likewise aid and encourage all other practicable measures which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armament.”

“Support for the principles of the Atlantic Charter and a pledge of cooperation to the utmost in giving effect to them, came from a meeting of ten governments in London shortly after Mr. Churchill returned from his ocean rendezvous. This declaration was signed on September 24 by the USSR and the nine governments of occupied Europe: Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia and by the representatives of General de Gaulle, of France.”

Nonetheless, the principles of the Atlantic Charter were remote from the realities of war in August 1941.

While Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed to the eight principles of the Atlantic Charter off the coast of Newfoundland, to Churchill’s frustration, America had still “made no commitments and was no nearer to war than before the ship board meeting.” (Gilbert, VI, p.1176) On August 16, while Churchill was still on the battleship Prince of Wales returning from his meeting with Roosevelt, an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed in Moscow giving the Soviet Union 10 million Pounds of British credit to replace lost war material from British stock. In the meantime, even as they were trying to prop Russia, the British suffered continuing and severe bomber losses over Germany. The strain was telling. Churchill increasingly resented criticism in the House of Commons and faced the prospect that Germany might destroy Russia before the United States entered the war, with the added prospect of Germany gaining control of Russian oilfields. In his live broadcast from Chequers on August 24, Churchill spoke of his meeting with Roosevelt. Perhaps trying to put the best face on the ongoing lack of formal U.S. commitment to the war, Churchill characterized the meeting as being “symbolic” and rather modestly introduced the Atlantic Charter as: “…a simple, rough-and-ready war-time statement of the goal towards which the British Commonwealth and the United States mean to make their way, and thus make a way for others to march with them…”

Not until December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, did America formally enter the war and not until October 1945 was the United Nations established, embodying the lofty principles of the Atlantic Charter. Even then, the nascent Cold War was already beginning, ensuring that a geo-political reality based on those noble principles would remain as remote as it was in Placentia Bay in August 1941. And as it remains today.