In July 2015, we wrote about Churchill’s article “The Truth About Hitler” in the December 1935 issue of The Strand Magazine. (Read that post HERE.)

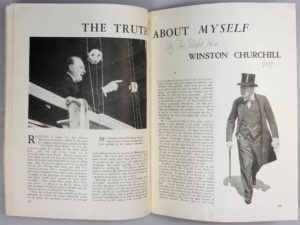

It seems overdue that we write about Churchill’s sequel and companion to that piece – his article “The Truth About Myself” in the January 1936 issue of The Strand Magazine. Just recently, we were preparing to list the first copy of this elusive article we have ever offered. So, with a glass of something brown in hand, I did something radical – I decided to sit down and read it. In the humble view of this Churchill aficionado it is one of the most compellingly revealing and introspective pieces of Churchill’s writing that I have seen in print.

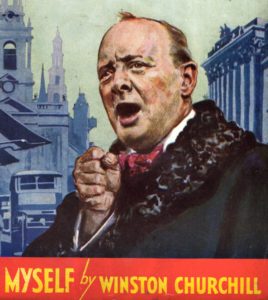

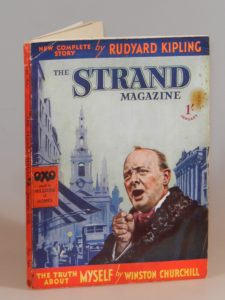

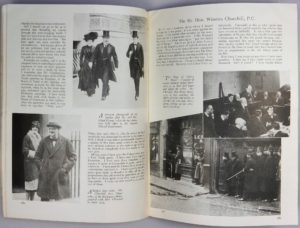

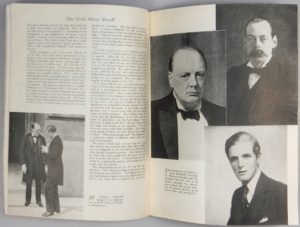

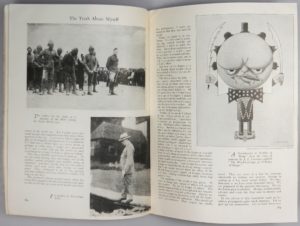

It is also an aesthetically striking and substantial piece, filling eleven pages, profusely illustrated with 17 photographs and a caricature. The article is prominently advertised on the front cover, with the title and author printed in bright yellow on a red banner below an orating and gesticulating image of Churchill.

It is also an aesthetically striking and substantial piece, filling eleven pages, profusely illustrated with 17 photographs and a caricature. The article is prominently advertised on the front cover, with the title and author printed in bright yellow on a red banner below an orating and gesticulating image of Churchill.

The counterpoint genesis of the article is not hard to fathom: “…it was as much as I know of the truth about him [Hitler]. And now the Editor wants me to write the truth about myself.” What is most remarkable about this article is how very non-Churchillian it struck me as being. Tonally heavy without the usual full measure of Churchillian wit and sparkle. Given the time, it is not surprising that Churchill used the article and the contrast to draw distinctions between pluralistic and dictatorial regimes. Nonetheless, the majority of the article does what is advertised and talks about Churchill himself: “…in thus revealing my feelings to you upon these great causes, I am perhaps straying too far from myself.”

The counterpoint genesis of the article is not hard to fathom: “…it was as much as I know of the truth about him [Hitler]. And now the Editor wants me to write the truth about myself.” What is most remarkable about this article is how very non-Churchillian it struck me as being. Tonally heavy without the usual full measure of Churchillian wit and sparkle. Given the time, it is not surprising that Churchill used the article and the contrast to draw distinctions between pluralistic and dictatorial regimes. Nonetheless, the majority of the article does what is advertised and talks about Churchill himself: “…in thus revealing my feelings to you upon these great causes, I am perhaps straying too far from myself.”

The article reverberates with the ostracism and pressure directed at Churchill in the midst of his 1930s “wilderness years” in which he was out of power and out of favor, persistently warning about the growing Nazi threat and his countrymen’s complacency. Albeit with a touch of humor (“…it is only the solicitations of our Editor which have induced me to devote a whole article to my own personality… not only am I a modest, but also an extremely benevolent man.”), Churchill directly defends his record against the allegations of his detractors.

The article reverberates with the ostracism and pressure directed at Churchill in the midst of his 1930s “wilderness years” in which he was out of power and out of favor, persistently warning about the growing Nazi threat and his countrymen’s complacency. Albeit with a touch of humor (“…it is only the solicitations of our Editor which have induced me to devote a whole article to my own personality… not only am I a modest, but also an extremely benevolent man.”), Churchill directly defends his record against the allegations of his detractors.

Against charges of inconsistency, Churchill states: “There are moments when I feel that I might make a case for being the only consistent politician.” Churchill then does just that, setting his own political evolutions in the context of the shifting political expediencies of others. He also defends his reputation as a contrarian: “…I have a tendency… to swim against the stream. I feel myself often irritated by the overstatement of any particular view… When I see… worshipful forces running in full cry together, my inclinations are to go the other way. I am sorry that it should be so…. However, that is how I feel instinctively.”

The striking, revealing bit is “I am sorry that it should be so.” Churchill even mitigates his strengths, confessing about his reputation as an orator: “The truth is that I am not a good speaker, and I only learned to speak, somehow or other, with exceptional difficulty and enormous practice.” The article is remarkable for oscillations between humble uncertainty and pugnacious self-confidence: “… I feel that most of my mistakes have been due to allowing my judgement to be overruled or deflected by other people’s stupid judgment.” It is in this context that Churchill defends the lingering stigma of the Dardanelles (“The disappointment of my life…”).

The striking, revealing bit is “I am sorry that it should be so.” Churchill even mitigates his strengths, confessing about his reputation as an orator: “The truth is that I am not a good speaker, and I only learned to speak, somehow or other, with exceptional difficulty and enormous practice.” The article is remarkable for oscillations between humble uncertainty and pugnacious self-confidence: “… I feel that most of my mistakes have been due to allowing my judgement to be overruled or deflected by other people’s stupid judgment.” It is in this context that Churchill defends the lingering stigma of the Dardanelles (“The disappointment of my life…”).

The article feels indelibly rooted in the middle of a decade that saw Churchill pass into his sixties with his own future as uncertain as that of his nation: “Young men ought to be ambitious… But such an experience as I have recorded is surely a cure for any form of personal ambition.” This is Churchill on the defensive – on topics ranging from hats (“I am usually caricatured with a tiny hat on my head… I do not delight in hats.”) to war-mongering (“Neither let me say do I delight in war…”)

The article feels indelibly rooted in the middle of a decade that saw Churchill pass into his sixties with his own future as uncertain as that of his nation: “Young men ought to be ambitious… But such an experience as I have recorded is surely a cure for any form of personal ambition.” This is Churchill on the defensive – on topics ranging from hats (“I am usually caricatured with a tiny hat on my head… I do not delight in hats.”) to war-mongering (“Neither let me say do I delight in war…”)

The article reads almost as a tortuous journey back to self-affirmation: “I am proud to feel the glow of counter-attack. I am glad to spend what is left of my mortal span in trying to rouse the good and brave people of England and of Britain and of her Empire…” The Churchill of the final paragraphs finally evokes the indomitable strength that would see his country through war ahead: “Although I see so harshly the dark side of things, yet by a queer contradiction I awake each morning with new hope and energy revived… I mean to do my part in this while life and strength remain.”

The article reads almost as a tortuous journey back to self-affirmation: “I am proud to feel the glow of counter-attack. I am glad to spend what is left of my mortal span in trying to rouse the good and brave people of England and of Britain and of her Empire…” The Churchill of the final paragraphs finally evokes the indomitable strength that would see his country through war ahead: “Although I see so harshly the dark side of things, yet by a queer contradiction I awake each morning with new hope and energy revived… I mean to do my part in this while life and strength remain.”

Some time ago, I tried (alas, unsuccessfully) to buy an early draft of Robert Frost’s poem Nothing Gold Can Stay. Here’s the final published version:

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

I loved the early draft precisely because it was not anywhere as good as the final version. In fact, as I researched the poem, I realized there were multiple early known drafts. Successively, these drafts evolved and coalesced into the splendid piece of writing above. But first, they were just drafts, promising, but not quite. Things requiring further effort and alchemy, the mallet and chisel and moment to coax greatness from mere possibility.

Some think it is disrespectful or demeaning to look for the imperfections underpinning greatness. (I once had a colleague accuse me of “effrontery” and “snarking” for pointing out that Thomas Jefferson impregnated one of his slaves.) Others think it irrelevant – that only the brightest facet of greatness is worth beholding. My own most fascinated regard is for the chancy, messy, iterative insistence of nascent greatness rather than the attainment of it.

I’m reading a lot into this article. Maybe it is the bottom of my glass talking, but it seems a window on the Churchill who might not have been, who was struggling to retain his essential faith in himself, feeling the purpose he needed gutter and dim and yet never go utterly “black dog” dark. A bereft but chin thrusting Churchill, bleeding ink and will, but abiding until his moment. I rather like him.