Yes, that’s a hell of a pretentious title. Or magnificently idealistic, depending on your perspective.

By happenstance, we recently acquired three works from three First World War leaders – all first-hand accounts of the ultimately ill-fated ideals threading the peace treaty that ended the First World War and the formation of the League of Nations. Both were intended to prevent a Second World War, the one that began only 20 years after the First.

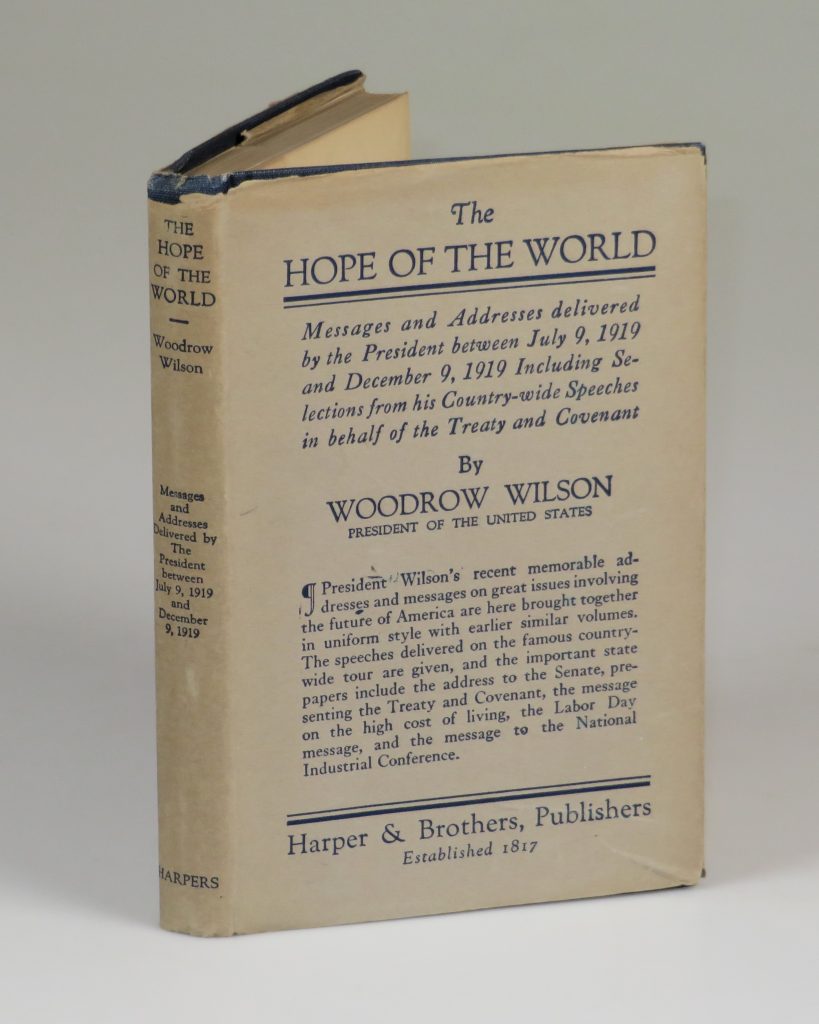

Woodrow Wilson and The Hope of the World

This little book – quite uncommon in the dust jacket – chronicles the failed advocacy of President Woodrow Wilson, at the end of the First World War, to persuade the United States to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the embryonic League of Nations. It contains “Messages and Addresses delivered by the President between July 9, 1919 and December 9, 1919”.

Before the United States entered the First World War in April 1917, President Wilson had sought to keep America out of the “European war” and “appealed to American citizens to ‘act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality.’” Yet even before a reluctant United States formally joined the war, President Woodrow Wilson pursued the idea of a League of Nations. “On 27 May 1916 the president announced his vision of collective security… calling for a new global community of democratic nations to preserve world peace and protect universal human rights.” Wilson anticipated that “a postwar League of Nations, … would replace Europe’s discredited balance of power and old alliances. ‘There must be, not a balance of power, but a community of power; not organized rivalries, but an organized common peace.’ This was his vision of a new ‘covenant’ among ‘democratic nations.’” At the Paris Peace Conference that convened in January 1919 at Versailles, Wilson “made drafting the covenant for this new international organization his top priority and insisted on its inclusion in the peace treaty.”

But while Wilson had an international constituency, he lacked a critical domestic one. “On his return home, Wilson presented the treaty to the U.S. Senate. Wilson’s 10 July 1919 speech presenting the Peace Treaty and League of Nations to the United States Senate for ratification is the first address in this volume: “We entered the war as the disinterested champions of right, and we interested ourselves in the terms of the peace in no other capacity”. He asserted “it was not easy to graft the new order of ideas on the old.” Wilson called the League of Nations “not merely an instrument to adjust and remedy old wrongs under a new treaty of peace”; it was, he said, the “only hope for mankind.”

The U.S. Senate, and particularly Henry Cabot Lodge, leader of the Republican majority, opposed Wilson and ratification. In the face of Senate opposition, “Wilson… decided to appeal directly to the American people and in September 1919 went on a speaking tour of western states.” However, Wilson “failed to mobilize public opinion effectively against Lodge and the Republican-controlled Senate. During the western tour, Wilson’s health collapsed. On 2 October 1919, back in Washington, he suffered a massive stroke.” With Wilson’s health, hope of U.S. participation also collapsed. “The Senate rejected the treaty on 19 November 1919 and again on 19 March 1920, thereby preventing the United States from joining the League of Nations – a critical absence that crippled the organization from its inception.

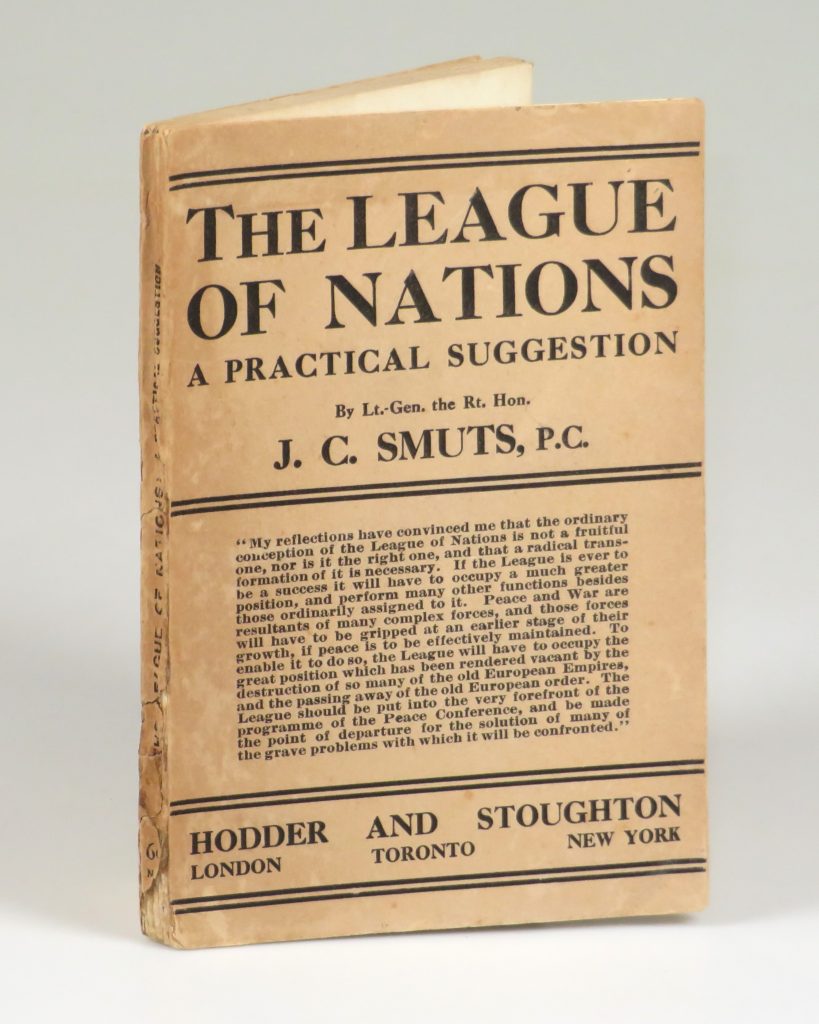

“A Practical Suggestion” from Jan Smuts

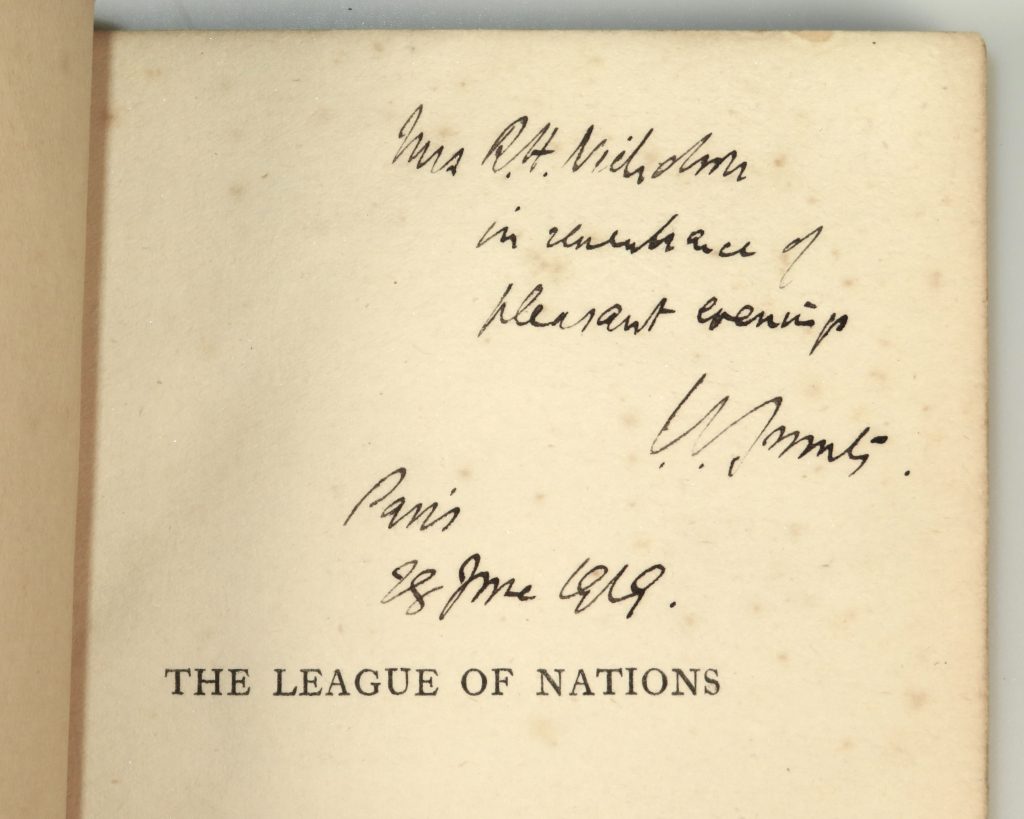

We were thrilled to recently acquire this copy of legendary South African and Commonwealth leader Jan Smuts’s book on the post-First World War Peace – thrilled because this copy was inscribed by Smuts in Paris in 1919.

Renowned South African soldier and statesman Jan Christiaan Smuts (1870-1950) served as both the 2nd (1919-1924) and 4th (1939-1948) Prime Minister of South Africa. He was an important figure in world politics, serving in the British War Cabinet in both the First and Second World Wars, and having a hand in the formation of both the League of Nations and the United Nations. Smuts was the only person to sign the peace treaties ending both the First and Second World Wars, and was the only person to sign the charters of both the League of Nations and of the United Nations. With respect to the former, “he may justly be called one of the principal progenitors of the League of Nations.”

During the First World War, “In the midst of his public duties, Smuts also re-established his ties with his Quaker, Liberal, and radical feminist friends… They… undoubtedly strengthened his liberal internationalism…. After armistice he was responsible for the demobilization plans of all the British departments and for compiling the British brief for the peace conference… Smuts’s experience of the South African War and the influence of his radical and pacifist friends deeply informed his opposition to the idea of total war, or indeed total surrender, and his keen advocacy of a new international order, embodied in his pamphlet The League of Nations, a Practical Suggestion… At the Paris peace conference, where with Botha he represented South Africa, Smuts continued to argue in vain for a magnanimous peace; he despaired that the Versailles treaty was ‘conceived on a wrong basis that… will prove utterly unstable and only serve to promote the anarchy which is rapidly overtaking Europe.’ He even threatened to resign as a delegate and lead a campaign against the treaty as ‘an abomination’… Nevertheless, when Lloyd George asked pointedly whether he was prepared to return the German colonies in south-west or east Africa, Smuts equivocated – and signed the treaty.” (ODNB)

In his work and in this book, Smuts had advocated that the nascent League of Nations “occupy the great position which has been rendered vacant by the destruction of so many of the old European Empires and the passing away of the old European order.” Smuts wanted the League to “be put in the very forefront of the programme of the Peace Conference and made the point of departure for the solution of so many of the grave problems with which it will be confronted.” Smuts’s vision was not realized. The failures of the post-World War I peace and the inadequacies of a League of Nations far more limited than Smuts had advocated helped precipitate the Second World War two decades after Smuts wrote this book. Smuts was destined to play an even greater role in that war and, in the wake of it, in the formation of the more robust and enduring institution of the United Nations.

David Lloyd George – a purpose rooted in “the present as much as the past”

The final work prompting this post is, like the two above, about the First World War settlement. But unlike the two works above, it was written on the eve of the Second World War.

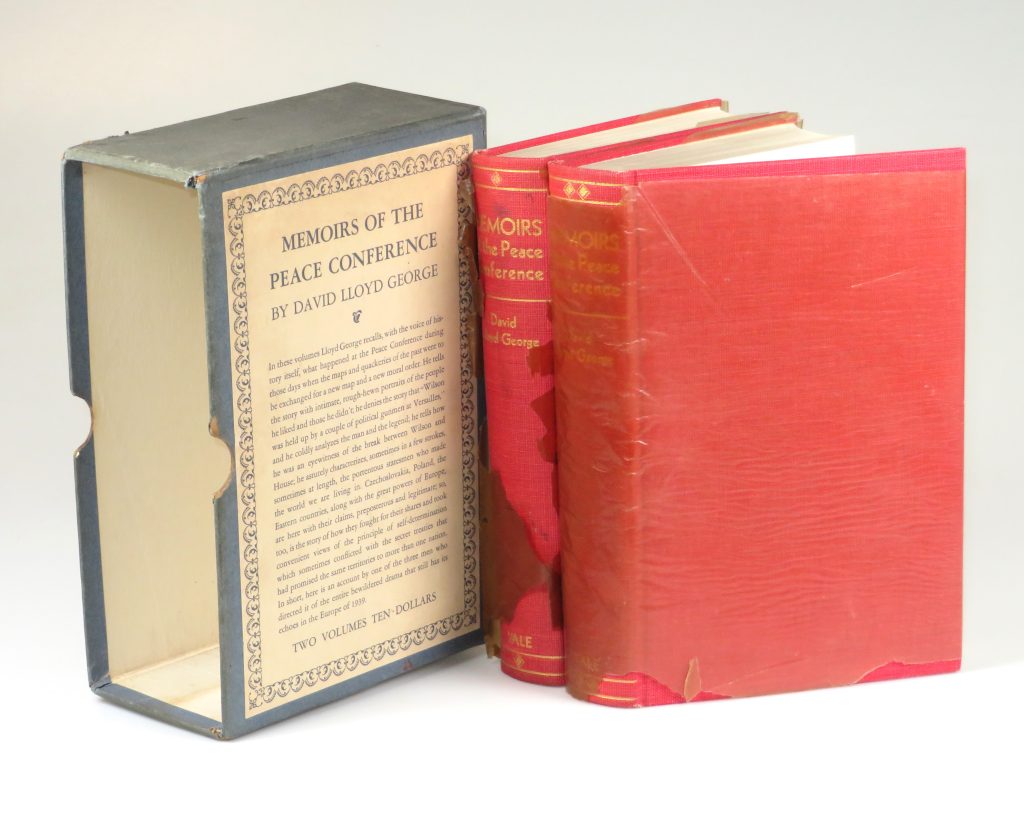

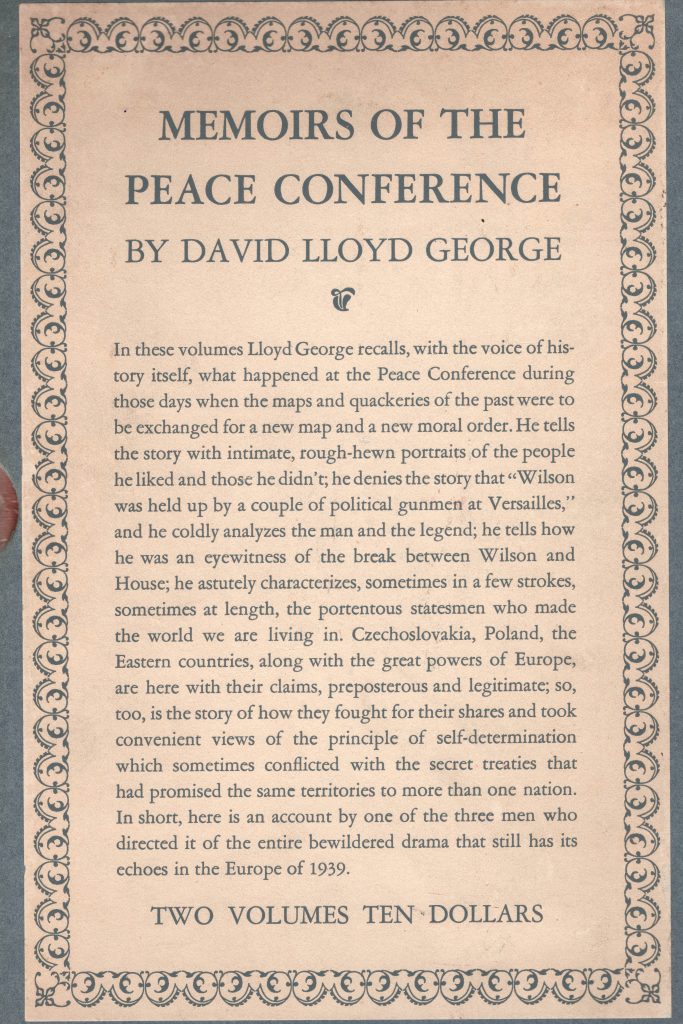

This is a two-volume, first edition, first printing set of David Lloyd Goerge’s memoirs of the peace conference that ended the First World War. As British Prime Minister from 1916-1922, Lloyd George was a principal architect of the conference and peace. This set captured our attention for its exceptional condition, still housed in the original publisher’s slipcase and retaining most of the original glassine dust wrappers. But the set is even more noteworthy for timing than for condition. It is no accident that Lloyd George was publishing his memoirs of the peace settlement that ended the First World War in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War. The extensive blurb on the slipcase concludes “an account by one of the three men who directed it of the entire bewildered drama that still has its echoes in the Europe of 1939.”

These two volumes were widely regarded as “the continuation and conclusion” to Lloyd George’s Memoirs of the First World War, published in six volumes between 1933 and 1936. In those six volumes, David Lloyd George was not just continuing, amid the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, to “debate on the strategy and ethics of the First World War.” He was “also implicitly arguing the case for a totally different approach towards Germany and international affairs in the 1930s. Their purpose was the present as much as the past.”

The same can be said of Memoirs of the Peace Conference. From 1936 on, “Lloyd George’s main preoccupation now was trying to reverse the effects of Versailles… As Germany fell into totalitarian dictatorship under Hitler, Lloyd George renewed his attacks on the reparations and unjust frontiers imposed on the defeated Germans. He was critical of the league and the failure to disarm as laid down in the peace treaties, and highly censorious of the French.” All of this was perhaps quite reasonable, but it was a time of great errors in judgement and Lloyd George was not immune. Lloyd George visited Hitler. Thereafter he wrote ecstatically of Hitler as ‘the greatest living German’, ‘the George Washington of Germany’ (Daily Express, 17 Sept 1936). It was a serious miscalculation… and did him much harm.” Nonetheless, “Right down to September 1939 he was a major political player.” Lloyd George “made one last great Commons speech, on 8 May 1940, when his devastating attack on Neville Chamberlain helped to bring the prime minister down and led to the succession of Winston Churchill.”

The presence of the past

The world learned at least something from the failures of the post-First World War peace. Although the world is riven with lesser conflicts, there have been no conflicts as internationally encompassing and devastatingly destructive as a world war for 80 years – four times the interval between the First and Second World Wars. The United Nations, successor institution to the League of Nations, has seen far more expansive international participation, and taken on broader and more robust roles in international affairs.

But the binding cords of international accord visibly fray. Disarmament treaties expire without being replaced. Longstanding treaties promising mutual aid among democratic nations falter or fray. Alliances among aggressor nations strengthen. International trade norms and rules are likewise flouted or dismantled. Efforts at new, multi-lateral trade agreements fall short of their potential as the United States suffers radical political oscillations and flirts with protectionism and isolationism. International courts issue indictments and warrants for wantonly belligerent heads of state, who shrug them with impunity. Freedom of speech and of the press and even citizen preference for, and confidence in, self-government precipitously declines.

When institutions and norms and values and even good will fail, there is history. To remind us that hope is the responsibility of each successive generation. That each generation is burdened with imperfection, ugly compromise, and failure. That relentless effort to achieve a comprehending awareness is not an esoteric intellectual pursuit, but a necessary foundation for constructively engaging and shaping the world. That books remind us. They fill shelves and rooms and whole libraries with the weight of what we have thought and tried. All so that we might remember and understand and, perhaps, be able to do better when we try again.

Cheers!

Churchill Book Collector

References: ODNB, ANB, Cambridge University Press