“Churchill Book Collector” implies a certain staple in our inventory. Namely books. But many of you know that there is more to our inventory than merely books – including ephemera, correspondence, and… photographs.

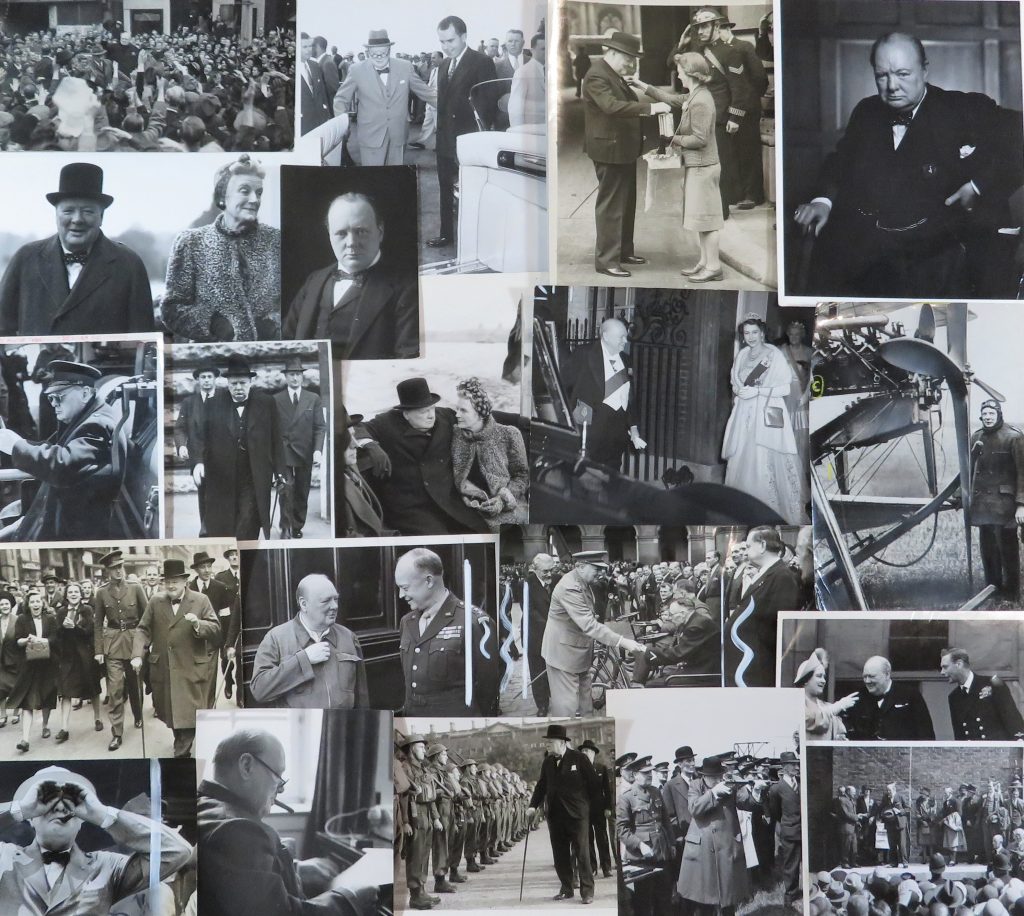

Over the past year, we have acquired a treasure trove of roughly 300 original press photographs of Winston Churchill, spanning the latter half of Churchill’s life, from the 1920s through 1964. In this blog post we give a brief history of these remarkable repositories of history and a preview of our offerings to come.

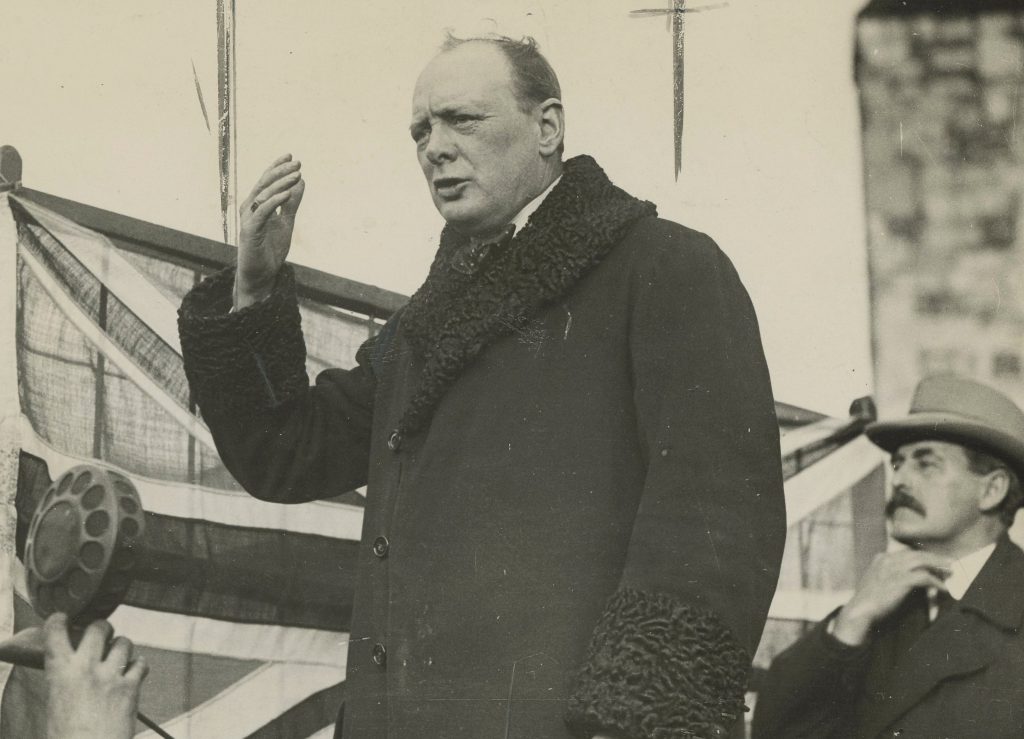

Through this remarkable collection of photographs we glimpse the vigorous ambitions of the young Cabinet minister, the isolation of his wilderness years, his leadership during the war years, his sojourn as leader of the opposition, his valedictory second premiership, and his final decade, when Churchill passed “into a living national memorial” of the time he had lived and the Nation, Empire, and free world he had served.

We have just listed the first tranche of 60 of these 300 photographs. These 60 original press photographs span Churchill’s resignation from his second and final premiership in April 1955 to his death in January 1965.

Churchill’s long career coincided with the evolution and ascendance of photojournalism. He witnessed its early years, remarking “It is the misfortune of a good many Members to encounter in our daily walks an increasing number of persons armed with cameras to take pictures for the illustrated Press which is so rapidly developing.” (letter of 26 June 1911 to Alfred Lyttelton) And during the war years he was a frequent subject of photojournalism’s golden age – often with noteworthy and occasionally with truly iconic results.

Soon after the development of photography in the mid 19th century, newspapers began to look for ways to supplement the written word with this new technology. For decades the only means of publication was through highly labor-intensive wood engravings reproduced by hand. In March 1880 – just half a decade after Churchill’s birth – The Daily Graphic of New York became the first paper to publish a halftone reproduction of a photograph. The development of this new photochemical reproduction process allowed for papers to begin to easily and quickly publish photographs.

These newly illustrated newspapers were an immediate success with the public, and a new profession, the photojournalist, was born. Only the largest newspapers had the resources necessary for in-house photographers, so news agencies were quickly established to meet the demand. Naturally, there was great incentive for each news agency to be the first to have available a photograph of a major event. All modes of transportation – including carrier pigeons – were used to speedily transport negatives to the agency bureaus where they were developed out and supplied to papers. This intense competition led to the Associated Press’s development of the most important photojournalistic inventions since the halftone, the Wirephoto.

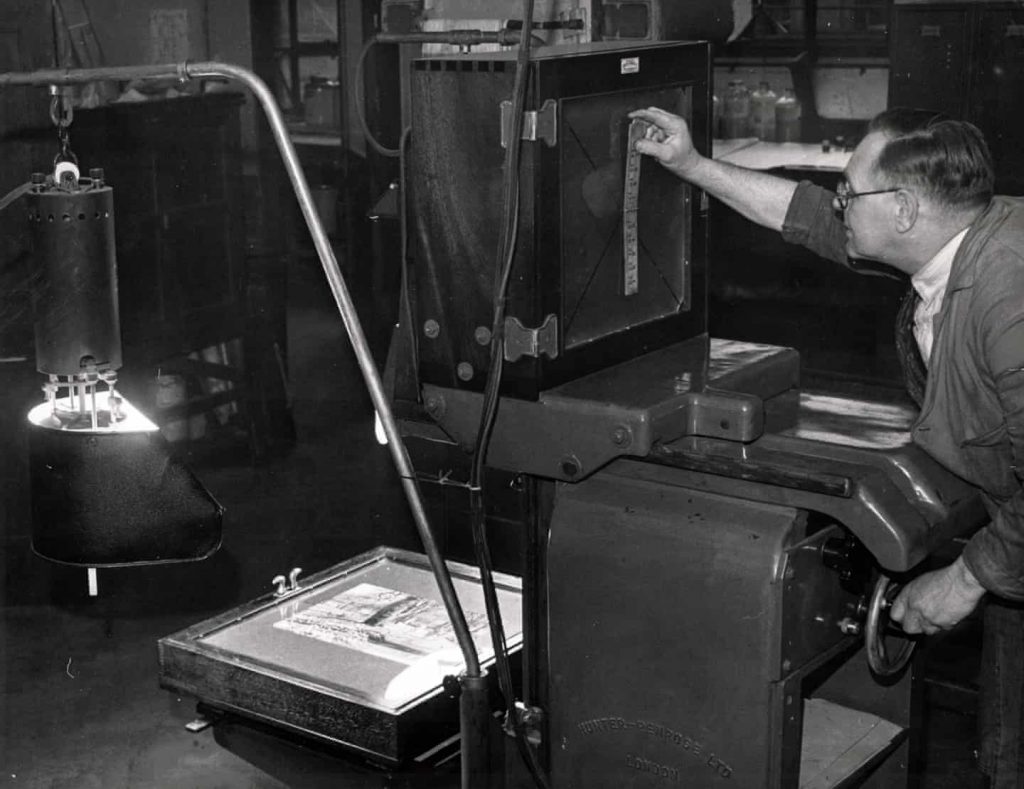

Developed in 1921, AP’s Wirephoto allowed for the first “instantaneous” transmission of visual images. The technology involved scanning photographic images and translating the image density into audio tones which could then be transmitted over dedicated phone lines. The audio transmission could then be received by special equipment that would translate the signal back into light, exposing a silver gelatin photographic support that could be processed in the dark room. Until 1954 – the year before Churchill would relinquish the premiership for the second and final time – nearly all press photos were printed using this process.

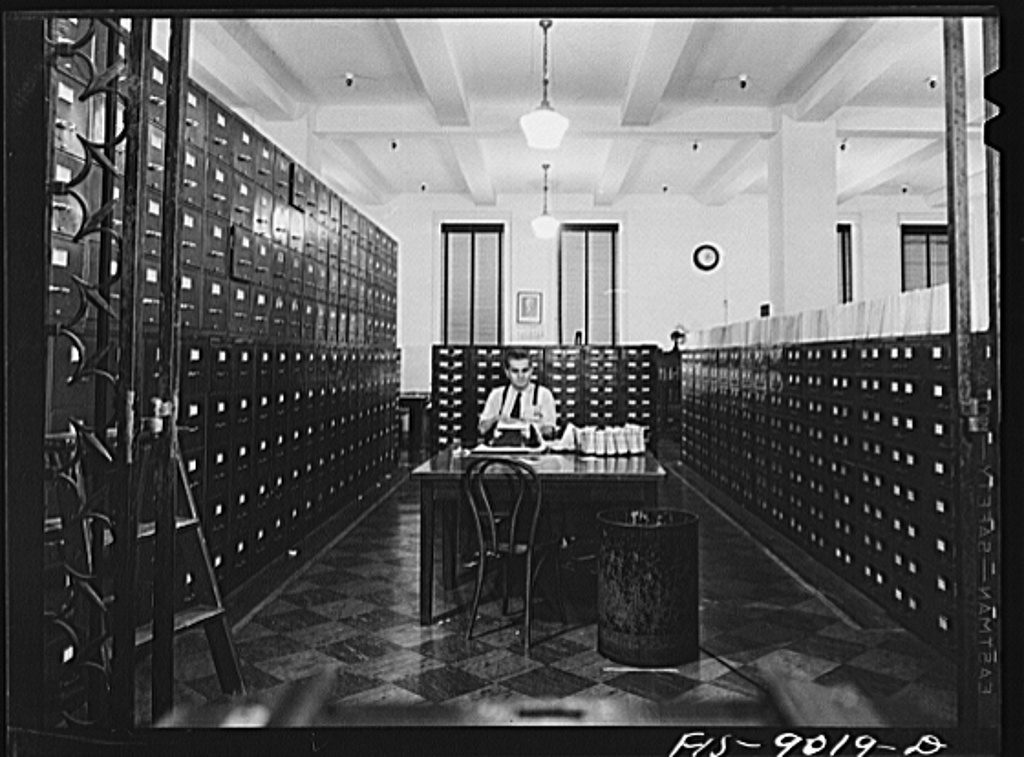

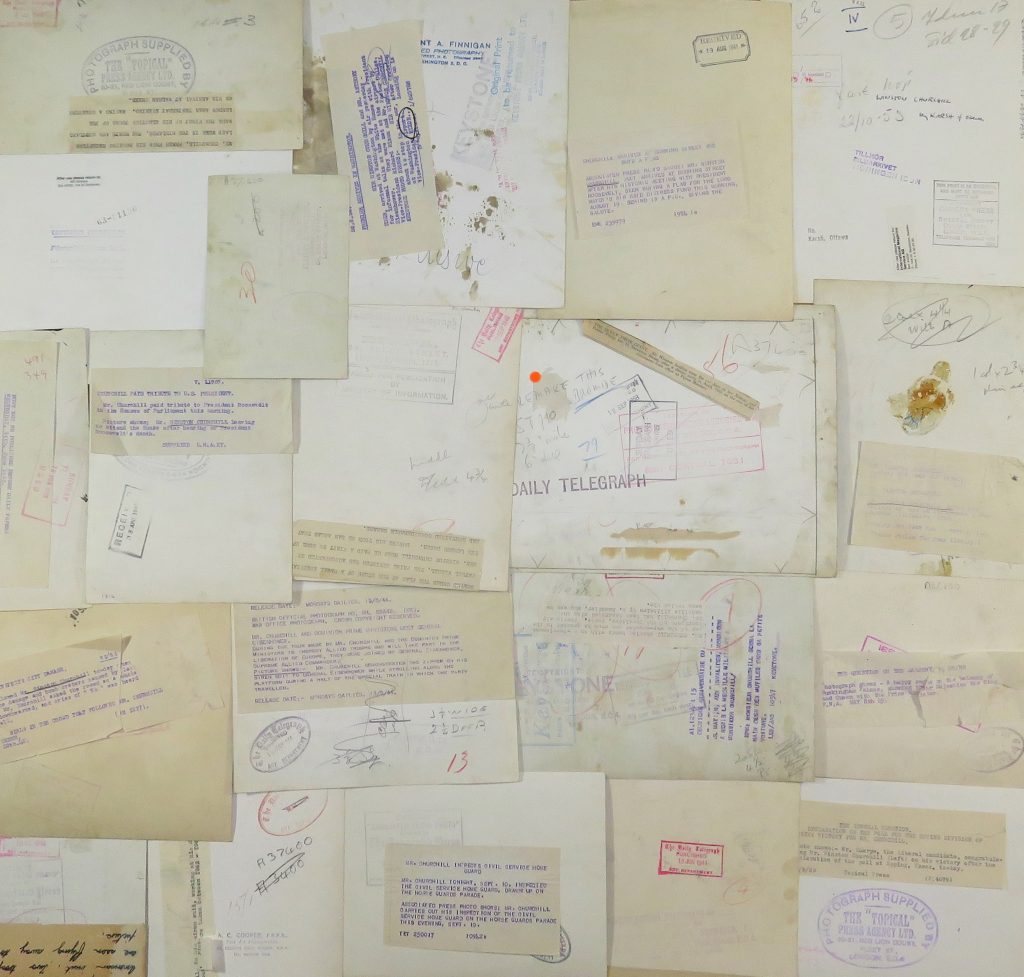

As newspapers began to collect photographs from staff photographers, news agencies, and third-party photographers expansive archives, called “photo morgues”, were established. Within these archives physical copies of all photographs published or deemed useful for future use were filed away. These archives often grew to hold more than a million images. Most newspapers’ filing processes included stamping the verso of each image with the copyright holder, publication notes, typed captions (often supplied by news agencies), reproduction notes, and clippings of the image’s appearance in print. During wartime censor information was occasionally also included. As a result, photo morgues serve as vast, rich archives of primary historical sources.

In addition to their historical importance, photo editing techniques of the early 20thcentury often make these unique and aesthetically fascinating visual objects. Before Photoshop made such edits possible at the click of a button, newspapers’ photo departments would often take brush, paint, pencil, and marker to the surface of photographs. These additions ranged from the mere adjustment to the total re-contextualization of a photo.

With the addition of paint these photographs become not only repositories of historical memory and technological artifacts but also striking pieces of vernacular art. And as the photographs were archived for reference and potential re-use, extensive notes were often made to the versos, including stamps and notations of provenance and captions.

In recent decades, as newspapers declined and publications increasingly turned to digital production, the contents of photo morgues have been made available for acquisition by libraries, archives, museums, and, occasionally, private parties such as Churchill Book Collector.

The photographs we will offer show a compelling slice of 20th century newspaper press photography through the prism of an individual who was integral to much of that century’s momentous history. The photographs come from a variety of sources, from standard news agencies to direct from the studios of noted photographers. The hand-applied edits range from mere contrast adjustments to the complete erasure of figures.

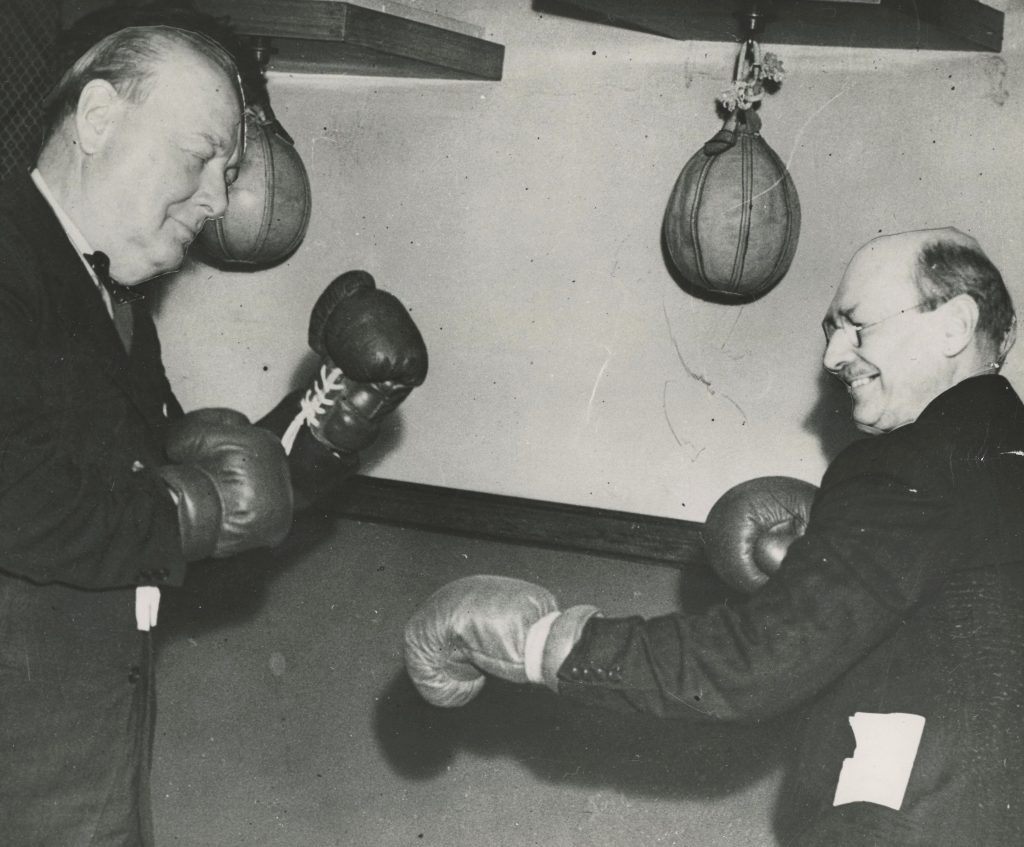

One remarkable photo, of Churchill and Attlee’s faces pasted onto the bodies of two sparring boxers, reminds us that photos mischieviously edited for humor have existed for longer than we might assume.

In this collection of press photographs, we see Churchill as a family man, his arm around Clementine in the midst of the Battle of Britain, or brushing the cheek of his grandchild. We see Churchill as a military leader, inspecting troops and firing guns.

We see Churchill the statesman with world leaders both expected (George VI and FDR) and more unexpected (Nixon and a Nazi leader).

We see Churchill the orator as he gives speeches and radio broadcasts.

And in the photos of Churchill’s final years we are reminded of the inescapable and inexorable toll of physical mortality, which disregards the longevity of words or deeds.

Which brings us full circle to the notion of why a bookseller trades in photographs.

As we have written before, published work has limitations inherent to the very acts of drafting and editing, of expert input, careful consideration, and diligent preparation. Published words, however luminous and illuminating, can find themselves separated from the vitality and immediacy of a moment or perspective.

Photographs are something different. More ephemeral, more candid, more distinctly in and of the moment. Able to impart a vital sense of things that no acclaimed book or carefully crafted speech – however Churchillian in mastery – can quite capture. So even though Churchill left us a wealth of published words, there is more yet to see and to feel from photographs.

At present we plan to release these images for sale in groupings, in roughly reverse chronological order, beginning with the first 60 we have just listed spanning Churchill’s final decade. We are likely to offer the final 100 or so in a dedicated catalogue released concurrent with the 36thAnnual Churchill Conference, to be held in Washington, D.C. 29-31 October 2019.We look forward to sharing with you the incredible wealth of history and photography contained within this archive of original press photographs of Winston. S. Churchill.

Click HERE to browse our entire listed inventory of photographs.