So, imagine Winston Churchill telling you to donate books.

We recently acquired an original Second World War poster featuring a lengthy August 1944 exhortation by Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill to donate reading material to the troops during the campaign to liberate Europe.

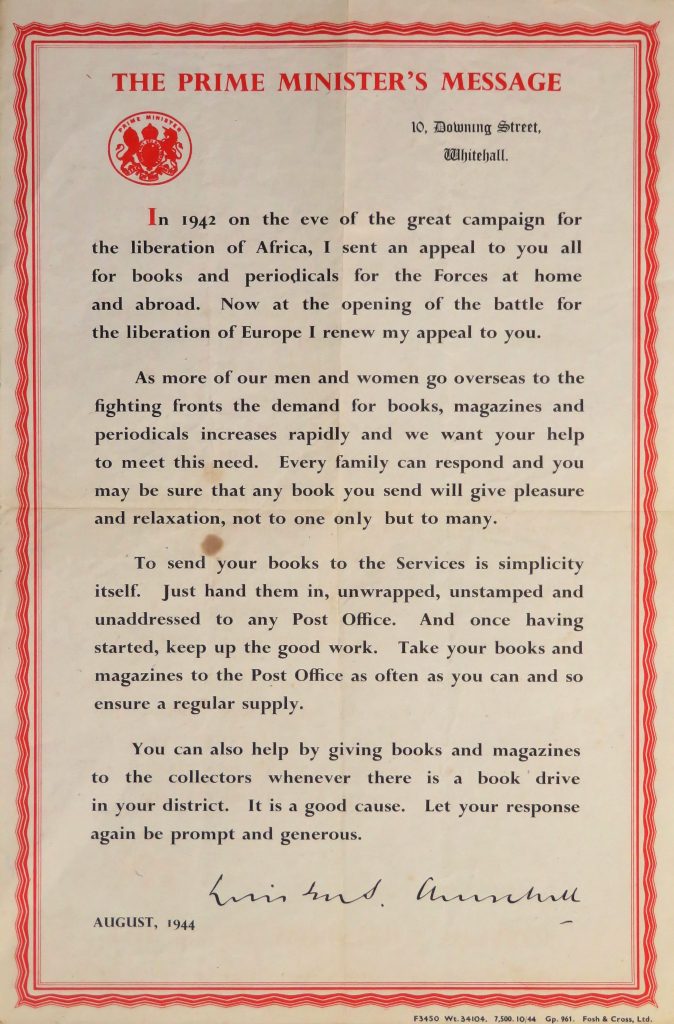

This is the first and only copy of this poster we have encountered. It measures 14.875 x 9.875 inches (37.78 x 25.08 cm) printed in red and black on white stock in a simulation of Churchill’s 10 Downing Street Stationery with an elaborate red border. The quite salutary overall effect is that of a giant letter from Churchill.

The red title reads, all in capital letters, “THE PRIME MINISTER’S MESSAGE” above “10 Downing Street, Whitehall”. The message, in four paragraphs, reads:

“In 1942 on the eve of the great campaign for Africa, I sent an appeal to you all for books and periodicals for the Forces at home and abroad. Now at the opening of the battle for the liberation of Europe I renew my appeal to you.

As more of our men and women go overseas to the fighting fronts the demand for books, magazines and periodicals increases rapidly and we want your help to meet this need. Every family can respond and you may be sure that any book you send will give pleasure and relaxation, not to one only but to many.

To send your books to the Services is simplicity itself. Just hand them in, unwrapped, unstamped and unaddressed to any Post Office. And once having started, keep up the good work. Take your books and magazines to the Post Office as often as you can and so ensure a regular supply.

You can also help by giving books and magazines to the collectors whenever there is a book drive in your district. It is a good cause. Let your response again be prompt and generous.”

The message ends with Churchill’s facsimile signature “Winston S. Churchill” and a printed date of “August, 1944”. Printed at the lower right margin of the poster the number “7,500” likely indicates the print run, “10/44” an apparent print date, and “Fosh & Cross, Ltd.” is presumably the printer.

As both a bibliophile and Churchill admirer, it is pretty much impossible not to gush over this item. Here is the only Prime Minister to ever win the Nobel Prize in Literature trying to see to the literary needs of his soldiers while in the middle of leading his nation during the Second World War.

If you are looking for an elegant symbol of fundamental difference between representative democracy and Hitler’s Third Reich, this might be it. While Churchill was appealing to his people to donate books, across the channel Hitler’s Germany was systematically burning them. Beginning in 1933, state sanctioned book burnings were organized, purging libraries and public and private collections of texts deemed “un-German”. By the war’s end, the Nazi’s destroyed an estimated 100 million books.

As referenced in this poster’s message, this wasn’t the first time Churchill had asked for books for the troops. In late 1942, during the campaign to liberate North Africa and shortly before Operation Torch, Churchill made an appeal to the British people for the donation of books. His message, printed in newspapers across the country, said: “If you had seen, as I have seen on my many visits to the Forces, and particularly in the Middle East, the need for something to read during the long hours off duty, and the pleasure and relief when that need is met, you would gladly look, and look again, through your bookshelves and give what you can.” The people of Britain responded enthusiastically. Newcastle reported donations that “filled 195 sacks and weighed close upon six tons.”

Anecdotally, we can assume that the books provided the intended comfort to soldiers on the front line. A moving letter by a battle-wounded American Marine to Betty Smith related how her novel, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, affected him: “A surge of confidence has swept through me and I feel that maybe a fellow has a fighting chance in this world after all. I’ll never be able to explain to you the gratitude and love that fill my heart in appreciation of what your book means to me.”

Few – if any – world leaders can claim Churchill’s deep, sustained, prolific intimacy with the printed word. In 1950, when he was 75, Churchill irreverently quipped “…already in 1900… I could boast to have written as many books as Moses, and I have not stopped writing them since, except when momentarily interrupted by war…” If anything, he was underselling his literary output. In 1953 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. By the time he died in 1965, Churchill had authored 58 books – not to mention 260 pamphlets, 840 articles, and roughly 9,000 pages of speeches.

Moreover, few world leaders would have better understood the value of reading material for the soldier abroad. Perhaps Churchill’s own soldiering youth was on his mind when he put his signature to this “Message” as wartime Prime Minister. Nearly half a century earlier, as a young cavalry officer, “When he sailed for India Churchill embarked on that process of self-education which was to prove so serviceable a substitute for the opportunities which he had neglected or rejected in his formal education… he eagerly devoured the books that were sent to him.” (Gilbert, Vol. I, p.318-19) It was as a young soldier abroad that Churchill learned not only to devour the printed word, but “discovered a great power of application which I did not think I possessed.” (Letter to his mother of 22 December 1897) Churchill wrote his first published book (The Story of the Malakand Field Force, 1898) while deployed abroad – a book about a campaign on the northwest frontier of colonial India in which he had fought and about which he had reported as a war correspondent.

Before the Second World War, at the height of appeasement and the nadir of his own popularity and political fortunes, Churchill spoke out against Nazi suppression of words and ideas. In his 16 October 1938 broadcast to the people of the United States, Churchill proclaimed:

“It is this very conflict of the spiritual and moral ideas which gives the free countries a great part of their strength. You see these dictators on their pedestals, surrounded by the bayonets of their soldiers and the truncheons of their police. On all sides they are guarded by masses of armed men, cannons, aeroplanes, fortifications, and the like – they boast and vaunt themselves before the world, yet in their hearts is unspoken fear. They are afraid of words and thoughts; words spoken abroad, thoughts stirring at home – all the more powerful because forbidden – terrify them. A little mouse of thought appears in the room, and even the mightiest potentates are thrown into panic. They make frantic efforts to bar our thoughts and words; they are afraid of the workings of the human mind.”

How terribly fitting that, six years later, Churchill would be the British Prime Minister soliciting book donations for the very troops – his troops – fighting to liberate Europe from Nazi dominion.

After he killed himself in his bunker on 30 April 1945, Hitler’s body was doused with petrol and unceremoniously set afire in the Reich Chancellery garden – not unlike the books he had defiled and destroyed.

In accordance with the freedom he had labored so hard to defend, less than a year after this poster was issued, Churchill lost – and graciously conceded – the free and fair British General Election that followed Victory in Europe. He occupied much of his time out of office writing the history of the war that he and his ideas had won.