An archaeologist’s job is to rescue the past from obscurity. So there is irony in seeing an archaeologist forgotten. That’s what nearly happened to Ann Axtell Morris (1900-1945) – one of America’s first female field archaeologists.

We have a natural affinity to archaeologists. As an Antiquarian bookseller, it’s our job to pay attention to sometimes obscure yet worthy parts of our past, and commend that past to the attention of others. Yet – with some chagrin – we confess that we did not know about Ann until a stroke of luck brought her life to our attention a few weeks ago.

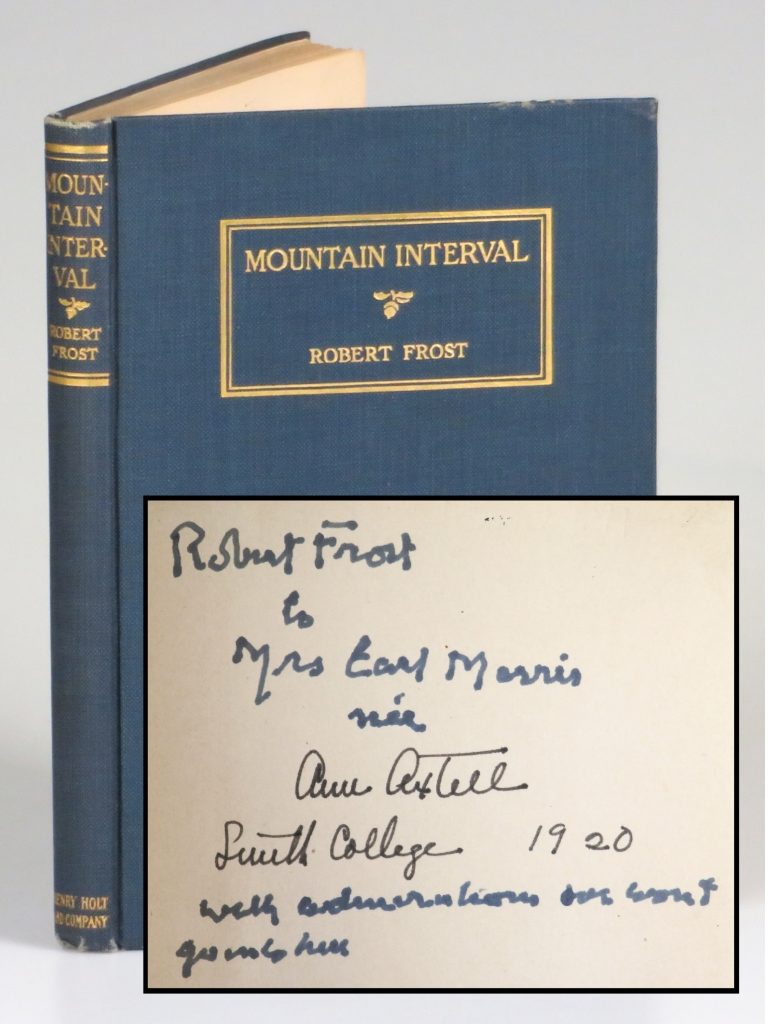

That stroke of luck was in the form of a first edition of Robert Frost’s third published book of poems, featuring a charmingly creative and warm inscription to Ann. It turns out that this inscription also involves the man who was the real-life archaeologist said to have inspired George Lucas’s and Steven Spielberg’s legendary big-screen archaeologist, Indiana Jones. But most interesting to us, this inscribed copy caused us to dig into the history of an extraordinary woman who merits remembrance, and whose own inspiration to film had to wait quite a bit longer.

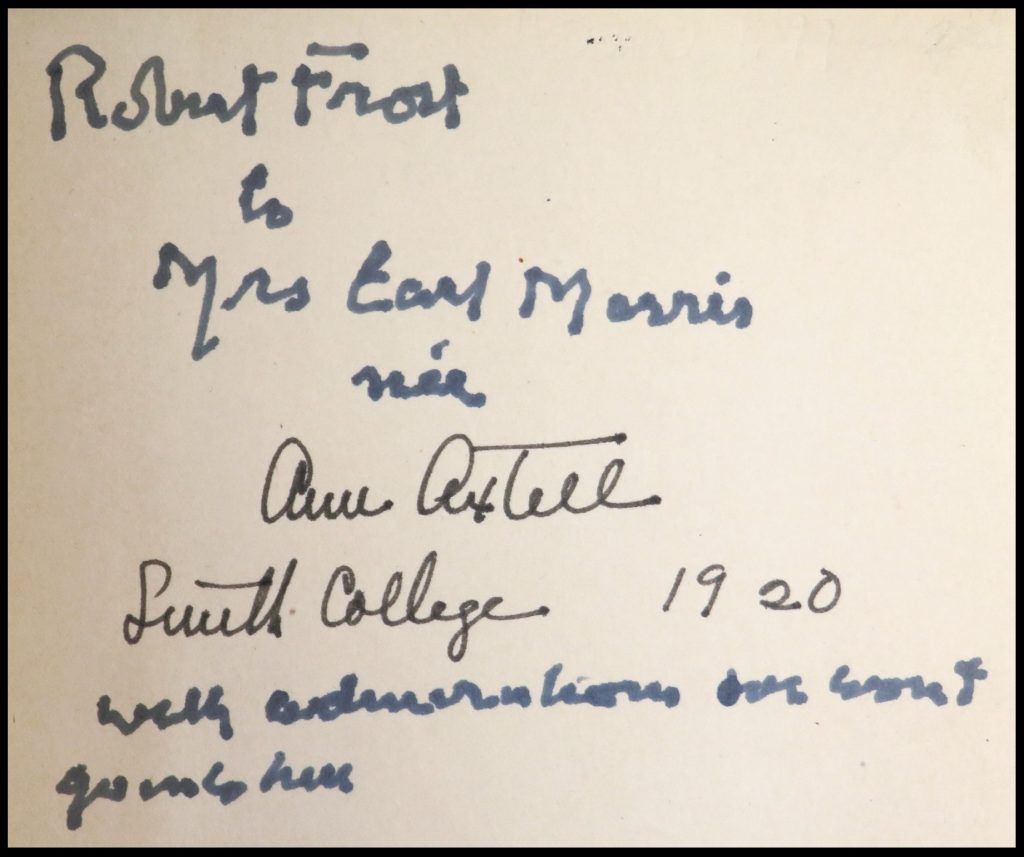

Ann received her bachelor’s degree from Smith College in 1922. She clearly acquired this book while a student. In two lines in black ink Axtell wrote on the front free endpaper “Ann Axtell | Smith College 1920”. Frost later conformed his own inscription to Axtell’s, writing above in four lines in dark blue “Robert Frost | to | Mrs. Earl Morris | née”. A further two lines below Ann’s own, Frost wrote “with admiration we won’t | go into here”. Well, in this blog post we finally go into it.

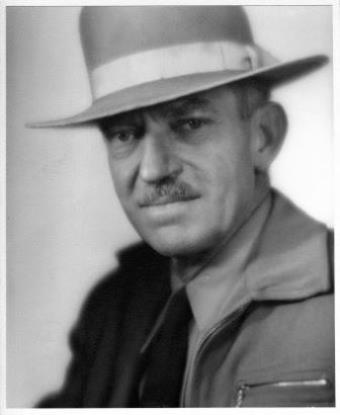

After graduation, Ann Axtel undertook field training with the American School of Prehistoric Research in France and then entered professional life as an archaeologist. The field was in a golden age; archaeology “had become more scientific and professionalized in the late 19th century.” There were considerable discoveries waiting to be made, an increasingly professional basis for making them, and strong public interest in what was being discovered. In this exciting climate, 1923 Ann married fellow archaeologist Earl Halstead Morris (1889-1956).

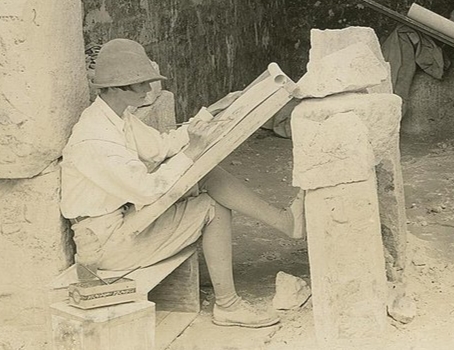

Fortunately, Ann and Earl shared professional passion. Beginning during their honeymoon, they excavated and explored ancient Native American sites in Arizona. While their work would take them to sites spanning Mesa Verde in Colorado to Aztec Ruins in New Mexico to a Mayan city in eastern Mexico, Arizona arguably yielded their most important contributions to archaeology. “Together, Ann and Earl wrote many studies on ancient lifeways within the American Southwest and Mexico.” Ann also wrote two popular books on her own, including Digging in the Southwest, “which upended conventional thinking about the Anasazi people”. Over the course of her career, “Ann developed methods to document architecture, petroglyphs and pictographs, and landscapes. Ann’s colorful drawings captured information that then-popular black-and-white photography would have lost.”

Certainly, all three individuals present in this inscription – Robert Frost, Earl Morris, and Ann Axtell Morris – labored for their opportunities.

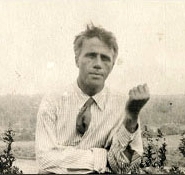

Frost had repeated flirtations with penury before he published his first book of poetry at the age of 40. And that only after relocating his family to England (“the place to be poor and to write poems”). In 1912 – the same year Robert Frost began his sojourn in England – Earl Morris dropped out of college to join an excavation in Guatemala.

By the time of his death, at age 66, Earl Morris had received numerous awards, including the Norlin Medal, an honorary doctorate, and the Alfred Vincent Kidder medal. And, as a notional inspiration for Indiana Jones, Earl Morris may have catalyzed legend and helped father the most famous of all archaeologists. By the time he died at age 88, Frost had won the Pulitzer prize for poetry four times, spent the final decade and a half of his life as “the most highly esteemed American poet of the twentieth century” with a host of academic and civic honors to his credit, and become the first poet to read in the program of a U.S. presidential inauguration.

Ann pursued her own path with similar passion and achievement, but with quite different obstacles. When she entered the field, archaeology was offering tremendous insights to the world and exciting opportunities for archaeologists… as long as you were not a woman. In archaeology, “women faced discrimination in employment, publication, and fieldwork.” As a result, Ann “often worked without pay and was passed over for opportunities that were instead offered to her husband.” In 1924, when she first arrived in Mexico for an excavation of a Mayan city in cooperation with the Carnegie Institute, Ann was told by the lead archaeologist to babysit his six-year-old daughter and act as hostess to visiting guests. Ann had to convince him to allow her to excavate a small, overlooked temple. Initially relegated to nanny status, Ann would eventually spend four seasons copying the Temple of the Warrior murals, and her final illustrations were published in Temple of the Warriors at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan, coauthored with Earl and a French painter, Jean Charlot.

Co-authorship was not just naturally collaboration, but often a prudent necessity. “Despite her accomplishments,” Ann’s work “was often buried in papers that bore her husband’s name or went entirely uncredited.” Ann wrote two books herself for which she intended to have a popular audience “in order to educate the public about the field. The publishers, however, marketed the books to older children because they did not recognize that women could write literature about archaeology for adults.”

There is poetic irony in the fact that it was the work of Ann’s life to foster greater understanding of the lives and culture of ancient Native Americans and Indigenous Mexicans whose complex societies had been overlooked.

There is further ironic poetry in the fact that this particular work is inscribed by Frost to Ann. Frost’s first decisively American publication is inscribed to one of America’s first female field archaeologists. The book and the inscription limn very different experiences for Robert Frost and Ann Axtell Morris. Mountain Interval was Frost’s third book of poetry, but the first for which the U.S. edition takes precedence; both A Boy’s Will and North of Boston – Frost’s first two books – were first published in Great Britain. When Mountain Interval was published, Frost was newly returned to the U.S. from England and establishing the reputation that would give him that rarest of experiences for a poet – to be recognized and even revered in his own lifetime. The year that Mountain Interval was published, Frost was made Phi Beta Kappa poet at Harvard – from which he had dropped out years before – and elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In Mountain Interval, Frost’s singular voice is clearly heard in some of his finest poems, such as “Birches,” “Out, Out–,” “The Hill Wife,” and “An Old Man’s Winter Night.” The volume opens with the poem “The Road Not Taken.” We can only imagine how a young woman aspiring to become an archaeologist read Frost’s words:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Ann’s voice has been harder to hear. Ann’s alma mater, where she was an undergraduate when she acquired this book, recognized her with an honorary masters degree in 1935. Unfortunately, her life was shortened by illness and alcoholism. She died ten years later at age 45. We can only speculate what role her professional marginalization played in cutting short her life, her career, and her contributions to her field. Nonetheless, recognition of Ann’s legacy has grown in recent years and “She is widely credited with helping open the field to other women and inspiring generations of readers with a passion for archaeology.”

To the point, one of Ann’s daughters entered her field, becoming both an archaeologist and professor. A film biography about Ann Axtell Morris titled Canyon Del Muerto premiers in 2022. Notably, it is the first time the Navajo Nation allowed a film crew into the magnificent red gorge known as Canyon del Muerto and the film was produced in close cooperation with descendants of the same Navajo with whom Ann worked nearly a century ago.

We will offer this book for sale later this year.

References: American National Biography, National Geographic, The Smithsonian, The U.S. National Park Service