One hundred years ago this Sunday, then-Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston S. Churchill accepted the resignation of his chief Arab affairs advisor T. E. Lawrence “of Arabia”. This ended the collaboration of two titanic twentieth century personalities in securing post-First World War peace and political stability in the Middle East. It did not end their friendship, which lasted the rest of Lawrence’s life.

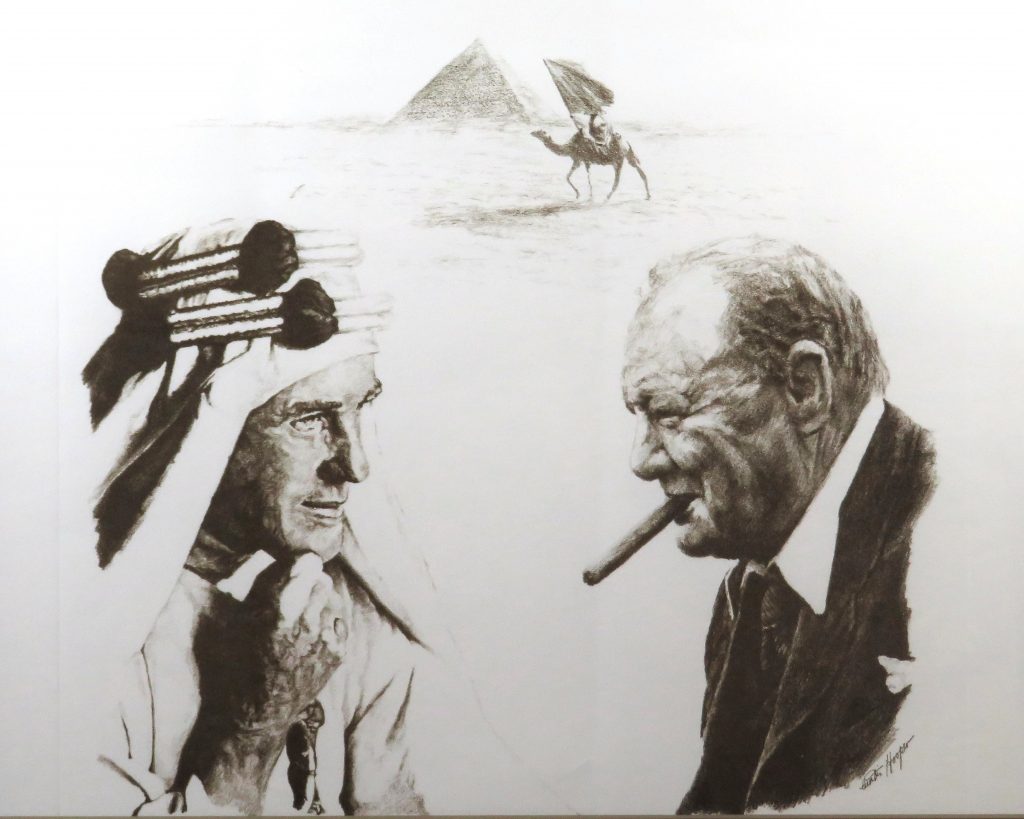

We are positively delighted, not to mention privileged, to offer for sale Churchill’s 17 July 1922 letter to Lawrence. The letter is accompanied by the original franked envelope addressed and initialed in Churchill’s hand. Both the letter and envelope are archivally framed with a limited and numbered intaglio drawing of Lawrence and Churchill by Curtis Hooper, signed and numbered by Churchill’s daughter, Sarah. Details about this item and the opportunity to purchase are found HERE.

But the longer story of the letter and underpinning collaboration and friendship is told in this blog post.

An unlikely basis for friendship

Churchill and Lawrence first met in the spring of 1919, after the First World War, which had profoundly tested and shaped the fortunes of both men.

Winston S. Churchill (1874-1965) had begun the war as First Lord of the Admiralty, a Cabinet position and the political head of the British Royal Navy. There he had led a significant and successful effort to modernize and ready the fleet for the war. But May 1915 saw Churchill scapegoated for failure in the Dardanelles and slaughter at Gallipoli and forced from his Cabinet position at the Admiralty. By November 1915 Churchill was serving at the Front as a lieutenant-colonel leading a battalion in the trenches. Before war’s end, Churchill was exonerated by the Dardanelles Commission and rejoined the Government, first as Minister of Munitions, then as Secretary of State for War and Air. When Churchill was appointed Colonial Secretary in early 1921, he had substantially recovered from both his political and corporeal near-death experiences in the First World War.

Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) arguably never recovered from the war. Lawrence’s remarkable odyssey as instigator, organizer, hero, and tragic figure of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War transformed him from an eccentric junior intelligence officer into “Lawrence of Arabia.” He spent the rest of his famously short life struggling to reconcile, reject, share, and repress this indelible experience.

Lawrence was catapulted to fame while acting (and arguably exceeding his role) as British liaison tasked with coalescing, coordinating, and supporting Arab revolt against Ottoman rule. In early 1918, Lawrence was captured in photographs and on film by American writer and promoter Lowell Thomas. The glamorous and romantic image of Lawrence became a transatlantic sensation and permanently alloyed with the man and his accomplishments. Lawrence, who never rose above lieutenant-colonel, vaulted all notions of military rank and restraint, propelled into legend. The fame thrust upon him became a hair shirt that Lawrence never shed.

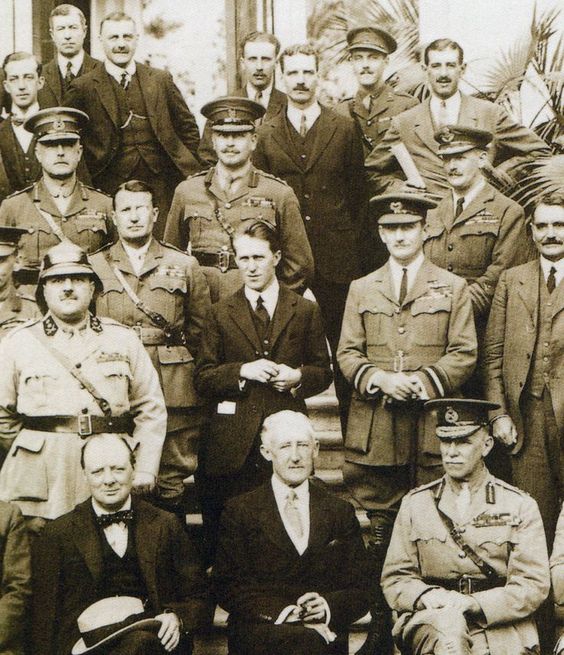

These are the proximate arcs of the two men who met for the first time in the spring of 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference following the First World War. As Churchill recalled many years later, Lawrence’s exploits were brought to the attention of Churchill. Hence the then-Minister for War and Air invited Lawrence to lunch – where he upbraided Lawrence for not accepting decorations from the King. Lawrence received Churchill’s rebukes with grace, and Churchill later learned that he had misunderstood the incident. It proved a suitably unlikely basis for an equally unlikely friendship.

Together at the Colonial Office

In early 1921, Winston Churchill accepted his eighth Cabinet appointment, becoming Colonial Secretary. Churchill’s brief included setting up a new Middle East Department. Swiftly after accepting the post, Churchill recruited T. E. Lawrence as a chief adviser on Arabian affairs and convened the Cairo Conference to settle borders of the Middle East. Together, Churchill and Lawrence rectified some of Lawrence’s unrealized wartime promises and aspirations by setting Lawrence’s First World War friend and comrade Feisal on the throne of Iraq, and making another comrade, Abdullah, Emir of Transjordan (and then, eventually, Jordan’s king). Of the effort, Lawrence would later write that the settlement was “the big achievement of my life: of which the war was a preparation.” (1927 letter to Robert Graves) During the year following the Cairo Conference, Lawrence continued to act as Churchill’s essential liaison and emissary to the Middle East, repeatedly dispatched thence to meet with key leaders, often alone, sometimes in secret and with plenipotentiary authority.

Nonetheless, “his mentality was that of a crusading politician rather than a civil servant.” That, combined with other complex factors, including “disinclination to follow a conventional career”, his authorial ambitions, and the tormented feelings he had about his sense of integrity and public adulation, limited Lawrence’s time in the Colonial Office. (Wilson, pp. 665-8) As Churchill himself later observed, “Lawrence was one of those beings whose pace of life was faster and more intense than the ordinary… He was not in complete harmony with the normal.” (Great Contemporaries) Lawrence had promised Churchill a year and given him just over that. Churchill granted Lawrence three months leave beginning 1 March 1922 to afford Lawrence time to work on his Seven Pillars of Wisdom manuscript. Lawrence never really returned.

The end of their collaboration

Churchill finally allowed Lawrence to leave the payroll of the Colonial Office at the beginning of July 1922.

The permanent Under-Secretary of Churchill’s new Middle East Department was Sir John Evelyn Shuckburgh (1877-1953), previously a senior official at the India Office. So it was that Lawrence, officially an adviser on Arabian affairs, addressed his 4 July 1922 letter of resignation to Shuckburgh:

My Dear Shuckburgh,

It seems to me that the time has come when I can fairly offer my resignation from the Middle East Department. You will remember that I was an emergency appointment, made because Mr. Churchill meant to introduce changes in our policy, and because he thought that my help would be useful during the expected stormy period.

Well, that was eighteen months ago; but since we ‘changed direction’, we have not had, I think, a British casualty in Palestine or Arabia or the Arab provinces of Irak. Political questions there are still, of course, and wide open; there always will be, but their expression and conduct has been growing steadily more constitutional. For long there has not been an outbreak of any kind; and while it would be foolish to seem too hopeful, yet at the same time I think there is no present prospect of trouble.

As I said, I think of myself as an emergency appointment. There are many other things I want to do and I came unwillingly in the first place. While things run along the present settled and routine lines I see no justification for the Department’s continuing my employment – and little for me to do if it is continued. So if Mr. Churchill permits, I shall be very glad to leave so prosperous a ship. I need hardly say that I am always at his disposal if ever there is a crisis, or in any job, small or big, for which he can convince me that I am necessary.”

Although the letter was clearly pitched to Churchill, despite the formality of being addressed to Shuckburgh, Lawrence concluded:

“I have to thank you personally for the very pleasant conditions under which I have worked in the Department itself.

yours sincerely,

T. E. Lawrence”

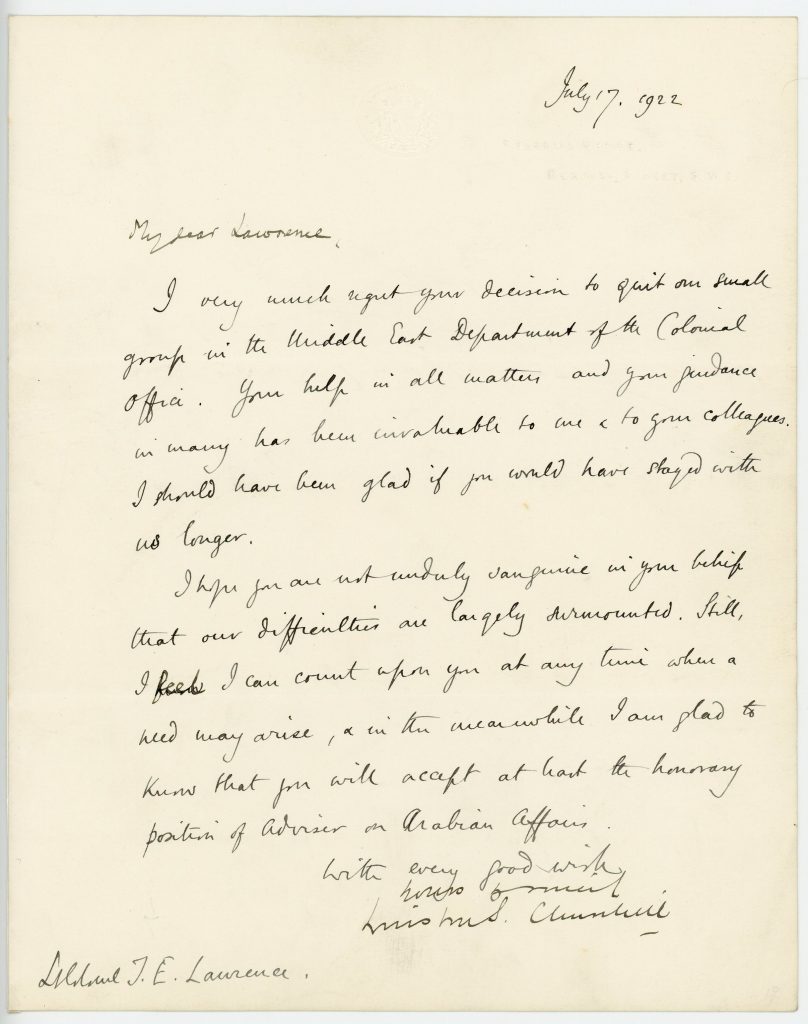

Churchill replied to Lawrence directly on 17 July 1922 in the letter we are privileged to offer.

The autograph letter signed by Churchill fills the entire 8 x 10 inch (20.3 x 25.4 cm) front panel of a single, folded sheet of Churchill’s “Colonial Office. Downing Street, S.W.1.” stationery with the Colonial Office embossed seal at the top center. Dated “July 17, 1922” with the salutation “My dear Lawrence”, the letter reads: “I very much regret your decision to quit our small group in the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office. Your help in all matters and your guidance in many has been invaluable to me & to your colleagues. I should have been glad if you would have stayed with us longer. I hope you are not unduly sanguine in your belief that our difficulties are largely surmounted. Still, I feel I can count upon you at any time where a need may arise, & in the meanwhile I am glad to know that you will accept at least the honorary position of Advisor on Arabian Affairs.” The two-line valediction is “With every good wish | yours sincerely” followed by Churchill’s signature, “Winston S. Churchill“. At the lower left corner is written “Lt Colonel T. E. Lawrence.”

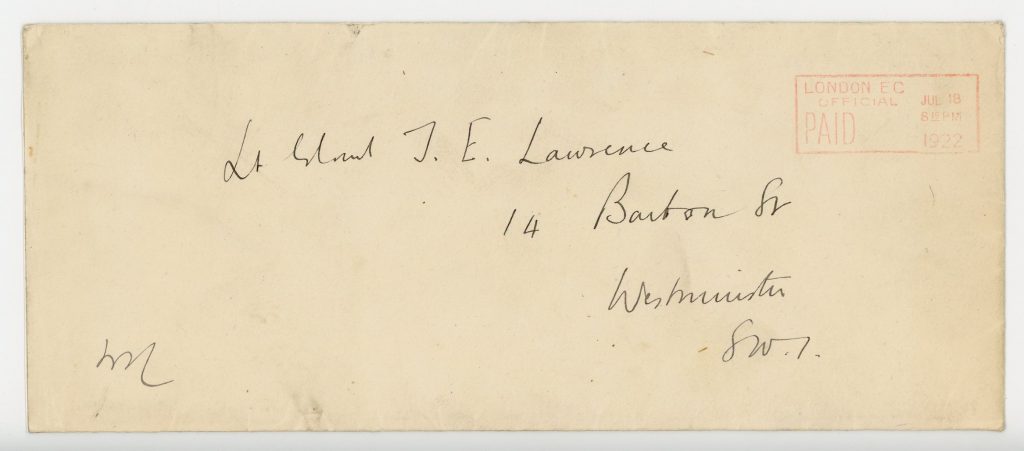

Accompanying the letter is the original, 8.875 x 3.75 inch (22.5 x 9.5 cm) franked envelope in which it was sent. The envelope flap features the same embossed Colonial Office seal as the stationery. In four lines, the letter is addressed: “Lt Colonel T. E. Lawrence | 14 Barton St | Westminster | S.W.1.” – the address of the attic room which was Lawrence’s London base for several years. Churchill initialed the lower left of the envelope “WSC”. The red ink “PAID” stamp at the upper right indicates that the letter was posted at “8:15 PM” on “JUL 18 1922”.

Lawrence’s official biographer, Jeremy Wilson, records that both letters were published in the 20 July 1922 edition of the Morning Post.

Lawrence’s expressed desire to depart from the Colonial Office with Churchill’s willing approval seems genuine. Lawrence wrote to a friend on 23 July “I liked Winston so much, and have such respect for him that I was determined to leave only with his good-will – and he took a long time to persuade!” As testified by Churchill’s letter of 17 July, Lawrence secured Churchill’s goodwill, along with his respect and appreciation. And four days after Churchill wrote his letter to Lawrence accepting his resignation, on 21 July Churchill also agreed to Lawrence’s desire to enlist in the Royal Air Force ranks. (Wilson, p.674)

After the Colonial Office

The end of Lawrence’s political partnership with Churchill marked the deliberate end of Lawrence’s brief, meteoric, and dramatic presence on the geopolitical stage. His remaining years would be spent on literary aspirations, in tortured efforts to encapsulate his First World War experience, in the feigned obscurity of his assumed names and enlistment in the Royal Air Force, on his diverse friendships, and, of course, on his motorcycles.

Though he was already two decades into his political career, Churchill’s own presence on the geopolitical stage would long continue to ramify and resonate, not reaching its storied apex until long after Lawrence’s death.

An enduring association

Their association remained warm for the rest of Lawrence’s life.

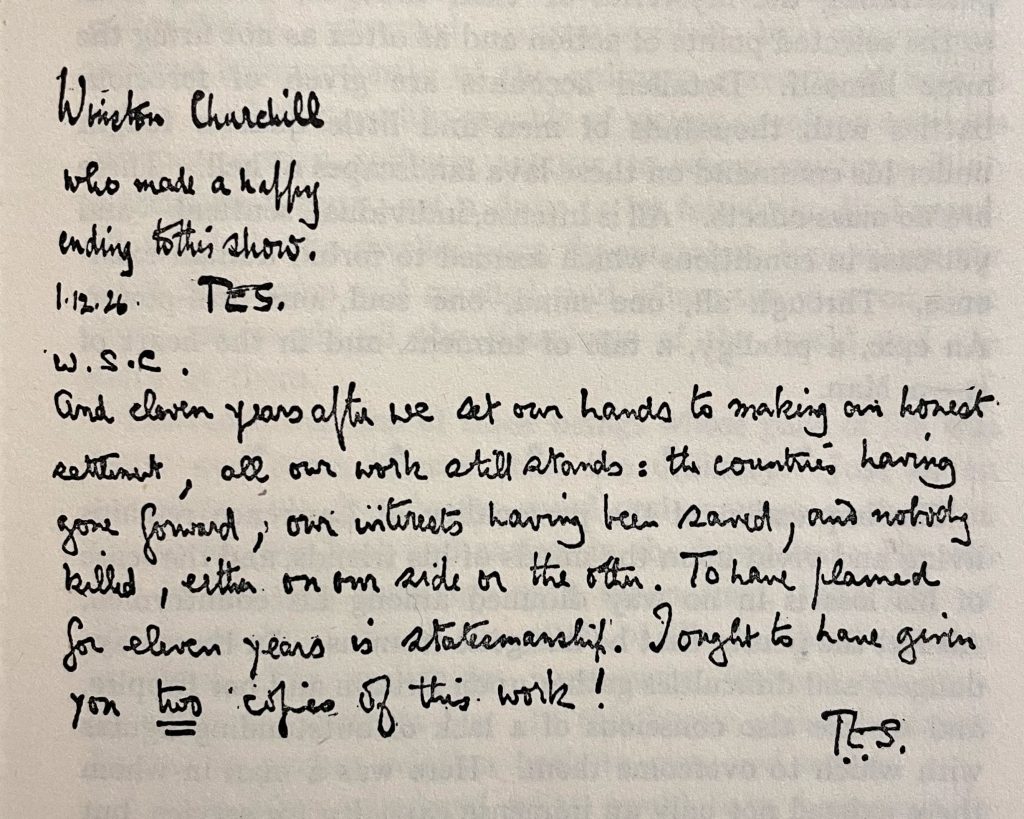

When Lawrence gifted his friend, Churchill, one of the precious few, magnificent copies of the Subscribers’ Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence addressed his presentation letter to “Winston Churchill, who made a happy ending to this show.” Churchill wrote to Lawrence with a level of effusive praise and enthusiasm hardly befitting a sober and seasoned statesman:

“I cannot tell you how thrilled I was to read it… Having gone on a three days’ visit to Paris, I never left my apartment except for meals… and lay all day and most of the night cuddling your bulky tome. The impression it produced was overpowering… The copy you gave me, with its inscription, is in every sense one of my most valuable possessions.” (letter of 16 May 1927)

Churchill had begun his career as an itinerant cavalry officer and war correspondent, eager to prove his mettle both on the battlefield and in print. And though he chose politics as his lifelong vocation, Churchill was, within his sphere, conspicuously headstrong and unorthodox. Hence it should be little surprise that Churchill so regarded such a remarkably literate, conspicuously gifted, iconoclastic, intrepid, and heroic paladin.

What is perhaps a bit surprising is that Churchill’s admiration was reciprocated by Lawrence. When Lawrence’s dear friends, Bernard and Charlotte Shaw, deprecated Churchill, Lawrence admonished them to be “kind to Winston”, telling them “I know that he is a bogey-man for all the left wing of the House of Commons… give him time, and the atmosphere to think, and he takes as gently broad a view of subjects as ordinary human kind can expect… his Colonial Administrations did more solid good to our native clients than all the good wishes of their loudest advocates… Winston in office does a great deal: and he is as fond of his friends as they are of him.” (Letter to Charlotte Shaw, 27 May 1927)

Diffident, ascetic, and distinctly uncomfortable in the limelight, devoid of political ambition, masochistic, and defined as much by personal demons as by any public persona, Lawrence was a different creature than Churchill. They differed in upbringing, temperament, education, and even stature – physical, social, and political. And yet the two men seemed to recognize in one another fundamentally kindred sensibilities and an unusually stubborn commitment to the integrity of their internal, often unconventional, sense of direction. For all the differences between them, these two men shared even greater differences from those around them. Perhaps that allowed them to appreciate one another.

An understanding

Churchill, famously a politician, was also a prolific and celebrated writer, a soldier and journalist, an ardent social reformer, an icon of the Conservative Party, a staunch defender of British imperialism, a pioneering internationalist, a bellicose adversary, a fair-minded peacemaker, a painter, a pilot, and even – though a poor one – a bricklayer.

In short, Churchill was capable of recognizing a polymath in Lawrence. Certainly, Lawrence became best known for his First World War role in Arabia and for the famous expression of this time and experience in his magnum opus, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. But Lawrence’s literary and intellectual reach far exceeded the world and words of Seven Pillars.

Churchill may have said it best: “Lawrence had a full measure of the versatility of genius. He had one of those master keys which unlock the doors of many kinds of treasure-houses. He was a savant as well as a soldier. He was an archaeologist as well as a man of action. He was an accomplished scholar as well as an Arab partisan. He was a mechanic as well as a philosopher. His background of somber experience and reflection only seemed to set forth more brightly the charm of and gaiety of his companionship, and the generous majesty of his nature.” (Great Contemporaries)

Despite the fact that his span of years was only half that of Churchill, Lawrence’s published works span crusader castles and ancient Greek translation to technical manuals on high-speed boats. His published volumes of correspondence reveal his engagement with an incredibly diverse array of foremost intellectual and political luminaries of the early twentieth century.

When Lawrence died, Churchill was among those at the small ceremony at St Nicholas’ Church in Moreton on 21 May 1935, and was reportedly moved to tears.

Postscript

In his 1937 posthumous profile of Lawrence in Great Contemporaries, Churchill wrote “I always felt that he was a man who held himself ready for a new call. While Lawrence lived one always felt – I certainly felt strongly – that some overpowering need would draw him from the modest path he chose to tread and set him once again in full action at the centre of memorable events.” Five years after Lawrence died, on 10 May 1940, Winston Churchill became wartime Prime Minister of beleaguered Britain. Had he lived, Lawrence would have been 51 years old. It is difficult to believe that his friend and former boss would not have called Lawrence back to service, invoking the phrase from his letter of 17 July 1922: “…I feel I can count upon you at any time when a need may arise…”