We write today about a compellingly expansive, eclectic, and interesting collection of material that provides a window on the world of, and adjacent to, Winston Churchill. Only one of our customers will own this archive, so we write about it to share it with everyone else.

Among the many items in this archive is a 29 September 1941 photograph of then-Prime Minister Churchill and his Private Office Second World War staff on the 10 Downing Street garden steps. The image conveys just what a small and intimate group it was. There are only nine figures in the image, including Churchill. At the back right is Charles Barker, who served Churchill’s entire wartime premiership as Chief Clerk, from 1940-1945.

This archive consists of material accumulated and saved by Barker. At the heart of the archive is a magnificent presentation copy of Churchill’s history of the First World War, a wartime edition presented to Barker as a gift for Christmas, 1942, featuring not only Churchill’s dated inscription, but also a typed and dated 10 Downing Street presentation slip. This item is but one of more than 70 individual items in the archive, ranging from books to correspondence and envelopes to photographs, to various mementos, including noteworthy invitations, tickets, and passes. All of these items are interesting. Many are treasures in their own right. Collectively they form a significant, singular, and compelling archive of Winston Churchill and his wartime leadership compiled by a member of his staff who served Churchill closely at 10 Downing Street throughout the Second World War.

Provenance

This archive came from the collection of British army veteran and noted Churchillian Major Alan Taylor-Smith (1928-2019) of Westerham, Kent, proximate to Churchill’s beloved country home, Chartwell. Not merely a collector, Smith also had his own research and notes on the recipient, as well as how this material was acquired, which are included with the archive.

Charles Barker

Barker, ultimately a 37-year career British civil servant, worked directly for Churchill for the entirety of Churchill’s wartime premiership, from May 1940 to July 1945. During the War, Barker “kept both the papers and the private secretaries in order… cheered up the doleful and was cynically destructive of pomposity. Life at 10 Downing Street would have been less efficient and less enjoyable without him.” (Colville, Winston Churchill and His Inner Circle, p.80)

In his book, The Fringes of Power, Barker’s Private Office colleague John ‘Jock’ Colville described Barker as “efficient and entertaining” and “popular with the Private Secretaries.” Apparently “an expert at old silver”, Barker would impress members of the War Cabinet by valuating their treasures. He also had a fondness for locks, and fancied himself an amateur locksmith. As related by Major Taylor-Smith, one of the first duties assigned to Barker by Churchill was to retrieve King George VI’s despatch box each morning and deliver it to Churchill at his bedside at 7AM. Barker reportedly amused Churchill when he showed him how the King’s despatch box could be opened without a key by simply removing the hidden screws. Barker had “two intelligent men, Pat Kinna and Donald MacKay, working under him and jointly they kept the office in apple-pie order.”

Treasures and locks are a conspicuous theme for this archive. But instead of silver and keys, there are wax seals pressed onto envelopes that read urgent, personal, and secret. There are official wartime photographs; there are staff passes that allow the holder to enter the rooms where wartime decisions were made and the theater in which the war was fought. Together, these artifacts encapsulate a significant period of service to crown and country from the perspective of a vital member of Churchill’s retinue at a singular moment in history.

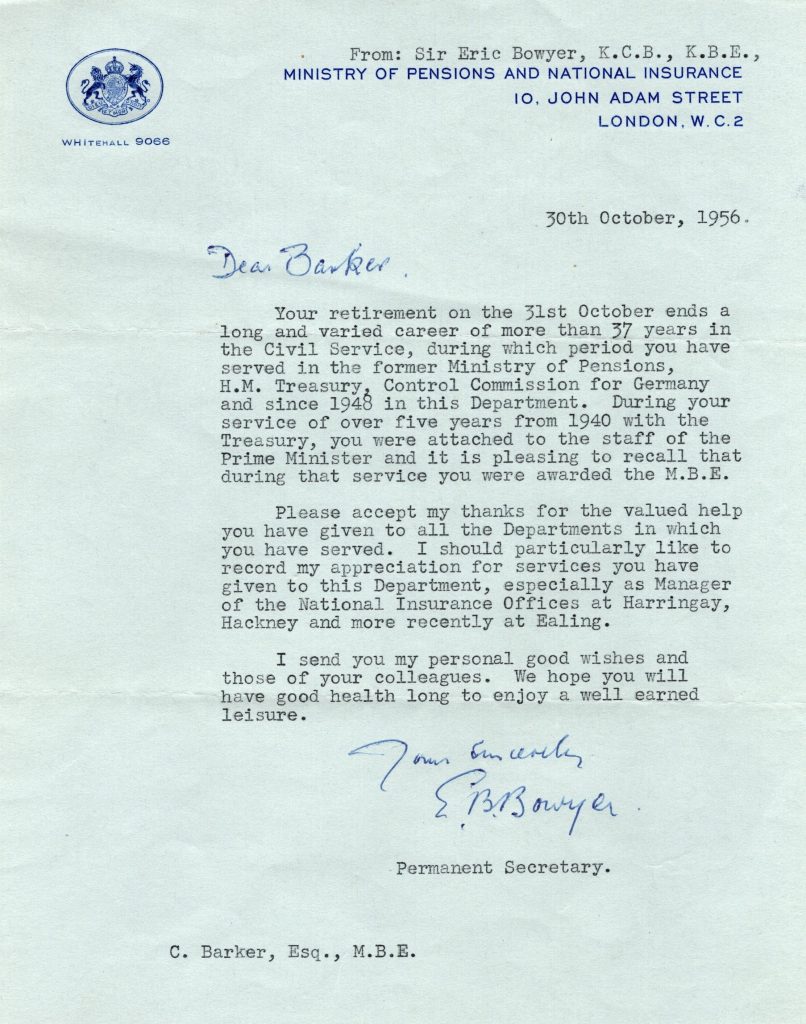

Present in the archive is a typed letter detailing the breadth and depth of Barker’s service, written by Sir Eric B. Bowyer, “Dear Barker, | your retirement on the 31st October [1956] ends a | long and varied career of more than 37 years in | the Civil Service, during which period you have | served the former Ministry of Pensions, | H.M. Treasury, Control Commission for Germany | and since 1948 in this department [ministry of pensions and national insurance]. During your | service of over five years from 1940 with the | Treasury, you were attached to the staff of the | Prime Minister and it is pleasing to recall that | during that service you were awarded the M.B.E.” Barker was awarded his M.B.E. in the 1946 New Year Honours, of course on Churchill’s recommendation; the December 1945 notification from “Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood” is among the items in this archive.

In his notes accompanying this archive, Major Alan Taylor-Smith reported that Charles Barker resided at 4, Larches Avenue, East Sheen, in south-west London. This is the address to which many letters to Baker in this archive are addressed. Barker attended East Sheen Grammar School and there he was eventually buried in Grave Plot 307 of the East Sheen Cemetery.

Burn Everything

Among the first duties Churchill assigned his new Chief Clerk in May 1940 was to regularly empty all the War Rooms and 10 Downing Street waste baskets then burn everything that might be deemed secret. This was not a janitorial duty, but a matter of national security. Information leaks were a constant fear, and the compartmentalization and containment was an essential practice. The entire D-day invasion, for example, was almost cancelled when twelve copies of the top-secret invasion plans blew out the window of the War Office of London and fluttered down onto the crowded street below. Historian David Howarth writes of that nail-biting event in his biography, “Staff officers pounded down the stairs, found eleven copies, and spent the next two hours in an agonized search for the twelfth. It had been picked up by a passer-by, who gave it to the sentry on the Horse Guards Parade on the opposite side of Whitehall. Who was this person? Would he be likely to gossip? Nobody ever knew.” To wit: gathering and burning documents was a vital and trusted task – far more mundane than James Bond variety secrecy, but deadly essential nonetheless.

So indispensable were Churchill’s wartime Private Office staff that in the event of an invasion there were detailed plans specifying that “Churchill, his family and his Private Office staff would be living at Spetchley House, near Worcester…” The evacuation plan was named ‘Black Move’ and “…this plan envisaged him [Churchill] and his party travelling to Worcestershire in six cars, along a carefully prearranged route, with Colville and Barker taking the current Cabinet papers in their cars, with a three-ton lorry to follow with the remaining Cabinet and other secret papers.” (Gilbert, Finest Hour, p.601).

History thanks Barker’s Private Office colleague, Jock Colville, for not quite following instructions; although it was forbidden under wartime regulations, Colville kept meticulous diaries which he locked nightly into his 10 Downing Street desk. Significant excerpts were eventually published decades later, making a noteworthy contribution to the known history of Churchill’s wartime administration.

Charles Barker may have been less overtly defiant, but – luckily for us – exercised his license to arson with some discretion and restraint. This archive indicates that Barker saved many items of interest that didn’t strictly require disposal for purposes of secrecy.

According to Major Taylor-Smith’s notes, “Charles decided to keep everything from the Cabinet waste paper baskets that was not Secret but interesting. He took it home to East Sheen and put into a leather suit case…” Taylor-Smith reports “I bought this filled suitcase in an auction in Battle, East Sussex after Barker died. Grace Hamblin, Winston’s Literary Secretary 1932-1945 and Clementine’s Companion 1945 to 1966 and first Curator of Chartwell and I sorted everything in the case…”

Certainly, not all of the treasures contained in that suitcase reside in this archive, but more than 70 individual items do.

Archive Contents

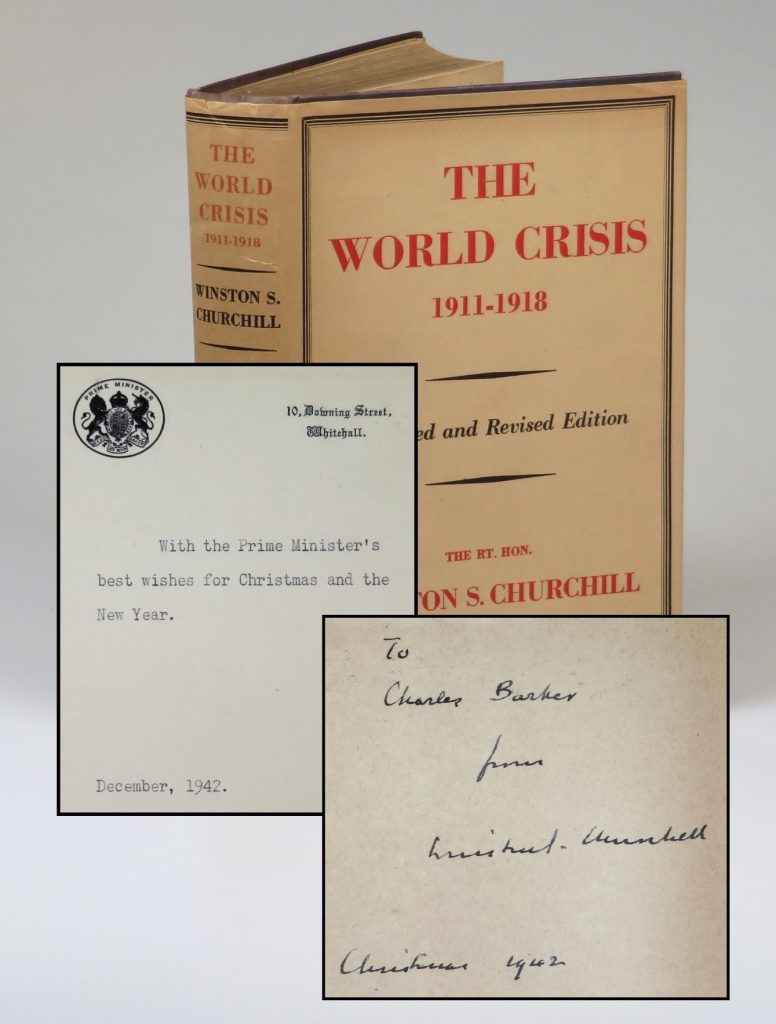

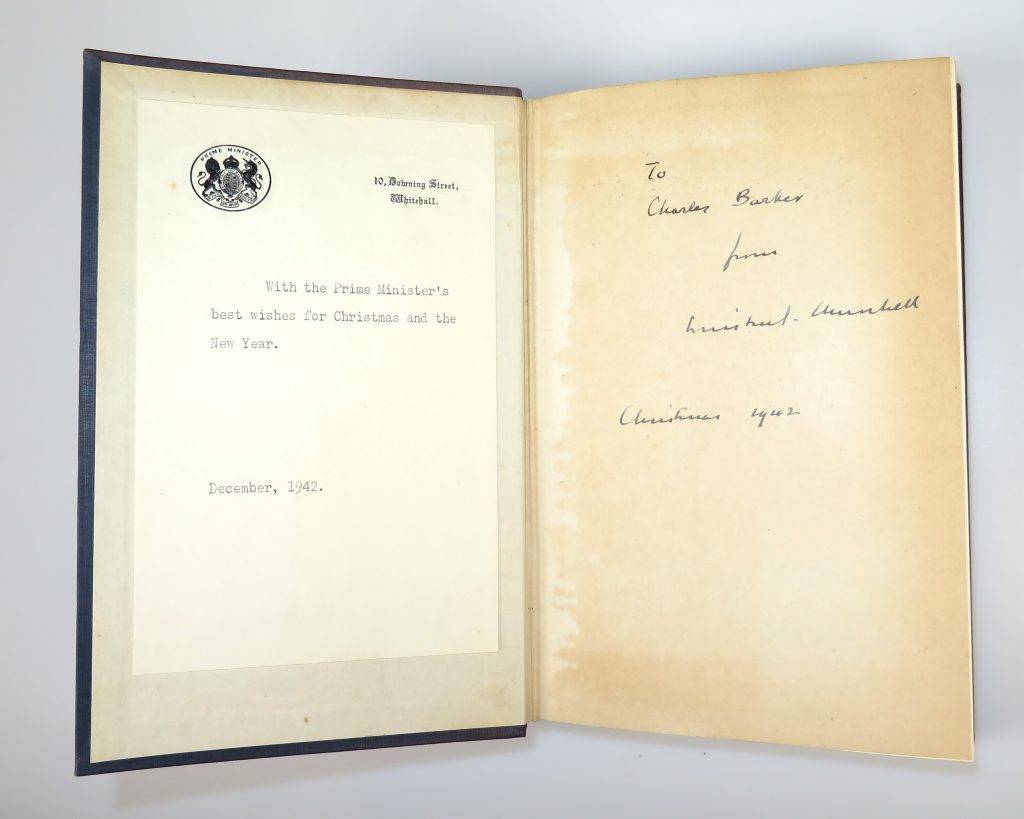

An inscribed presentation copy of The World Crisis

This copy of the first Second World War issue of Churchill’s acclaimed history of the First World War is inscribed entirely in Churchill’s hand in five lines on the front free endpaper recto: “To | Charles Barker | from | Winston Churchill | Christmas 1942”. Tipped onto to facing front pastedown is a presentation note on 10 Downing Street stationery with the typed message: “With the Prime Minister’s | best wishes for Christmas and the | New Year | December 1942.”

This first abridged and revised edition – The World Crisis 1911-1918 – was published by Thornton Butterworth just as Churchill was beginning his “wilderness years” decade. Churchill spent nearly the entirety of the 1930s out of power and out of favor, frequently at odds with both his Government and prevailing public sentiment. But in 1940 Churchill became wartime Prime Minister. And also in 1940, Thornton Butterworth went under and a different publisher, Macmillan, acquired the rights to several of Churchill’s books. This inscribed presentation copy is the 1941 first printing of the wartime Macmillan edition.

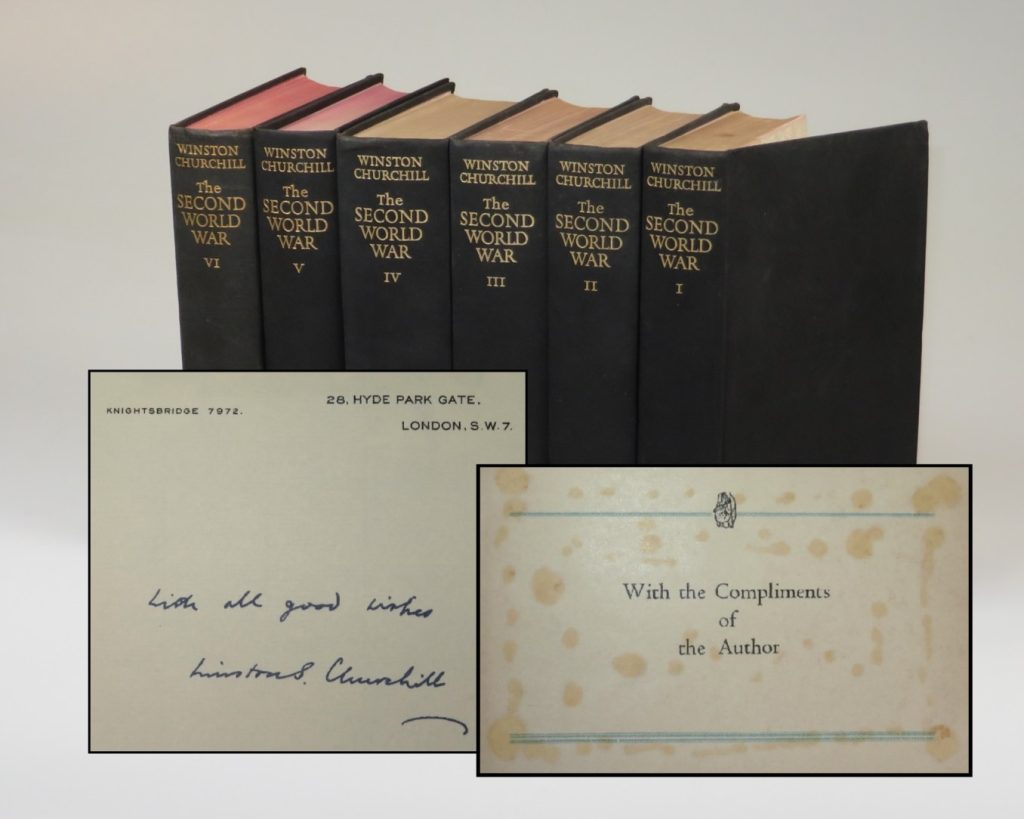

Barker’s six-volume, first edition set of The Second World War

This full, six-volume, British first edition set features manuscript facsimile compliments slips, a printed compliments card, and Charles Barker’s name. Five volumes are the first printing of the first edition; Volume IV is the second printing of the first edition. Laid into Volume I (formerly tipped on but now loose) is a compliments slip printed on Churchill’s Hyde Park Gate stationery with a facsimile autograph message in Churchill’s hand: “With all good wishes | Winston S. Churchill”. “Charles Barker’s Copy” is written in pencil on the Volume I half title. Tipped onto the Volume II pastedown is a plain compliments slip with a facsimile autograph message in Churchill’s hand: “With all good wishes | from | Winston S. Churchill”. “Charles Barker’s Copy” is written in pencil on the blank recto preceding the half title. Tipped onto the Volume III half title is a publisher’s presentation card printed “With the Compliments | of | the Author” and “Charles Barker’s Copy” is written in pencil on the blank recto preceding the half title. A simpler “Charles Barker” is written in pencil on the Volume IV blank recto preceding the half title. Tipped onto the Volume VI front free endpaper verso is a plain compliments slip with a facsimile autograph message in Churchill’s hand: “With all good wishes | from | Winston S. Churchill”.

Personal correspondence

There are 16 letters addressed to Barker spanning 1945 to 1968. 10 of these letters retain their original envelopes. The majority of the correspondence is from fellow Private Office staff. 7 letters are on 10 Downing Street stationery, 2 are on Buckingham Palace stationery, 1 on Foreign Office stationery, 1 on House of Commons stationery, and 1 on Colonial Office stationery

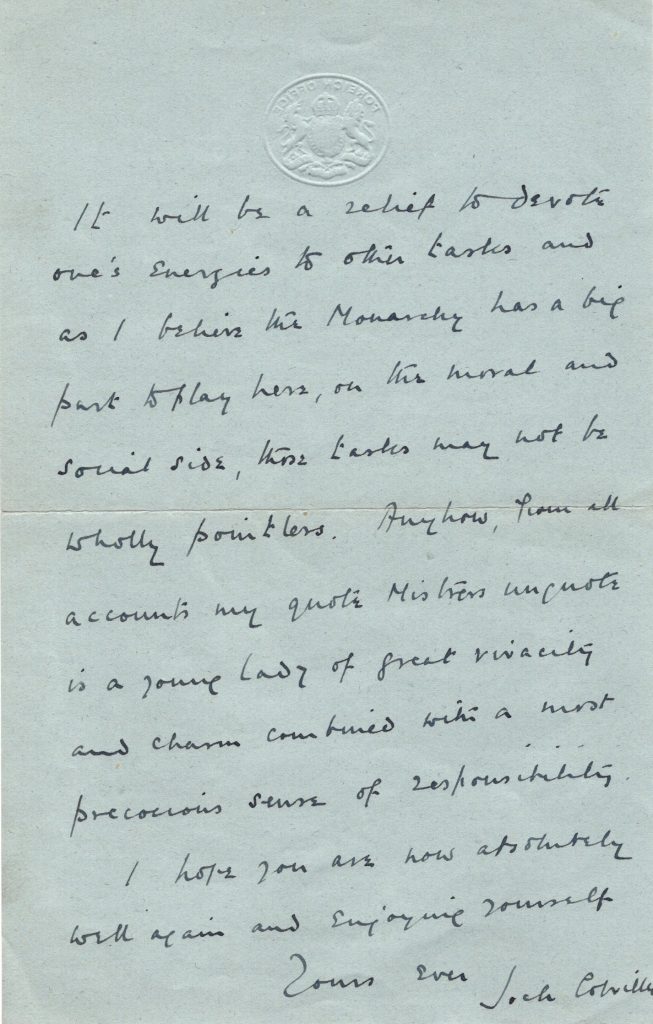

6 letters are from Jock Colville. Sir John ‘Jock’ Rupert Colville, CB, CVO (1915-1987) served Churchill’s two premierships, interrupted only by his active service as an RAF pilot between October 1941 and December 1943. In the years between Churchill’s premierships, Colville served as Private Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II (while she was still Princess Elizabeth). His letters to Barker are full of delicious quips and glimpses. In a 13 July 1947 letter on Foreign Office stationery, Colville reports on his impending departure for a new post as private secretary to Princess Elizabeth: “The foreign scene is dismal in these days and one’s soul shrivels before the negative, endlessly uncreative and relentless obstructed policy which our gallant Allies oblige us to pursue. It will be a relief to devote one’s energies to other tasks… From all accounts my quote Mistress unquote is a young lady of great vivacity and charm combined with a most precocious sense of responsibility.” In a 4 November 1947 letter on Buckingham Palace stationery Colville reports “I showed your letter of the 30th October to The Princess Elizabeth who was delighted that her speech at Clydeside should have had such an admirable affect [sic] in Germany.” In a 7 November 1951, newly returned with Churchill to 10 Downing Street, Colville writes “The old Man is full of vigour but more benign than ever.”

A 4 November 1952 letter from Anthony Bevir on 10 Downing Street stationery refers to an cryptic commitment to celebrate with “two dozen oysters a head” when an “Archbishopric falls vacant in my time.” Sir Anthony Bevir, KCVO, CBE (1895-1977) served as private secretary to both Churchill and Attlee (1940-1955).

A letter from Brendan Bracken on House of Commons stationery intriguingly offers Barker a job prospect. Brendan Bracken, 1st Viscount Bracken, PC (1901-1958) was a journalist, Member of Parliament, and wartime Parliamentary Private Secretary and Minister of Information to Winston Churchill. Bracken was created Viscount in 1952. On 17 November 1947 he wrote to Barker commending to him a job writing a feature in The Telegraph in the employ of Lord Camrose.

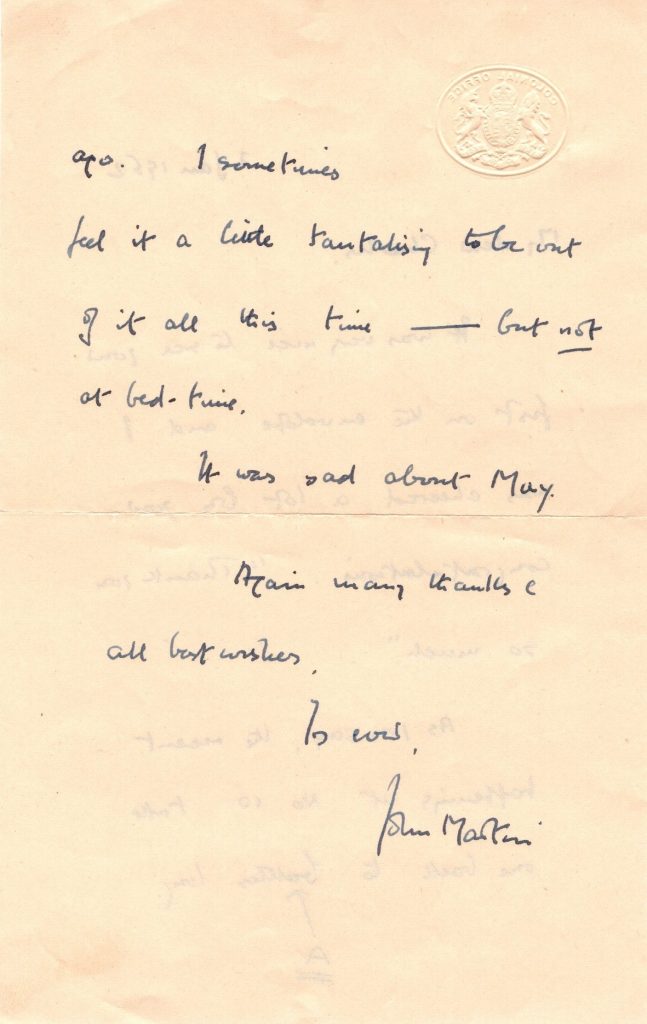

2 letters are from John Martin. Sir John Martin, KCMG, CB, CVO (1904-1991) served as a private secretary to Churchill throughout the Second World War and was knighted in 1952. He wrote to Barker on 2 January 1952 “…the recent happenings at No 10 take me back to battles long ago. I sometimes feel it a little tantalizing to be out of it this time…”

2 letters are from Sheila Minto, both on 10 Downing Street stationery and full of 10 Downing Street doings and scuttlebutt. Her handwriting is challenging to parse, but the content is tantalizing. Sheila Minto, LVO, MBE (1908-1994), nicknamed ‘The Queen Bee’, served as a chief administrator of Number 10 Downing Street through eight prime ministers.

Envelopes

There are 12 additional envelopes without correspondence. These are testimony to how seriously Barker took his charge from Churchill. Clearly Barker observed the edict of secrecy and either secured or destroyed the letters, but – whether because of the contents they held, their severable appeal, or both – he kept the envelopes.

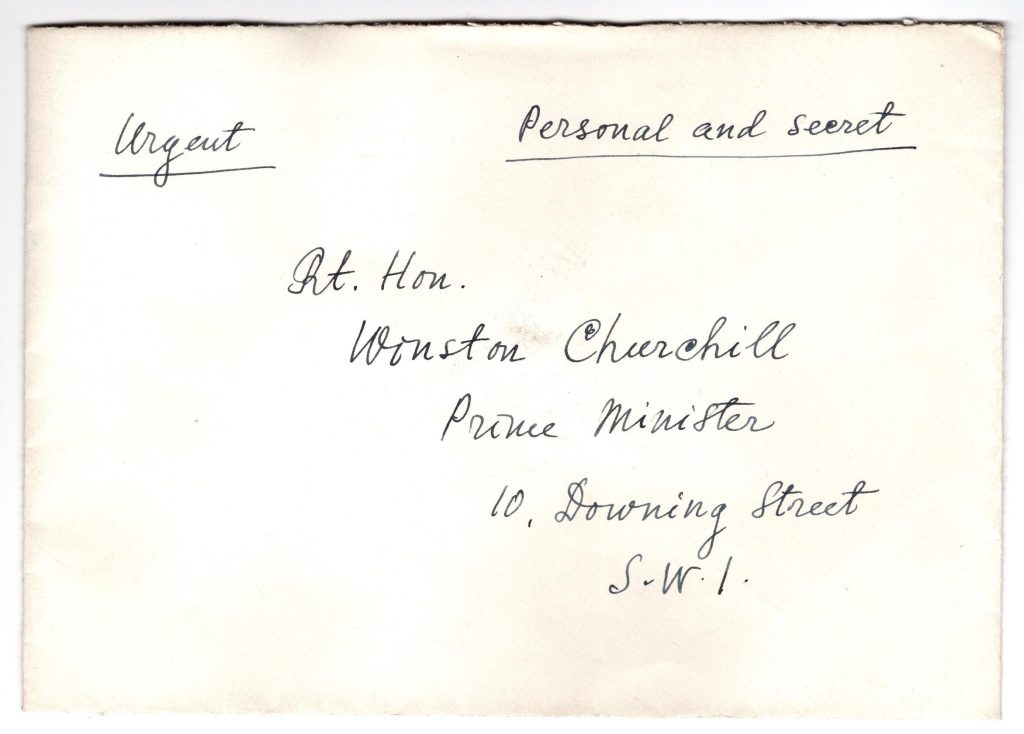

Two of the envelopes are hand-addressed to Churchill, one marked both “Urgent” and “Personal and secret”, the other merely “Personal and secret”, both featuring Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s wax insignia seal securing the flap. Another hand-addressed envelope, from The Princess Alexandra of Greece, features her insignia seal in silver wax securing the flap. A large, franked, string-secured manilla envelope conveyed a photograph hand-addressed directly to Churchill. A 10 May 1944 “VIA TRANS-ATLANTIC AIRMAIL” envelope addressed to Jock Colville from “Empire Information” in Canada was opened and resealed with a notably official sticker printed “OPENED BY | EXAMINER 4092”. Other envelopes are addressed either to Barker’s Private Office colleagues – namely Jock Colville and John Peck – or to Barker himself.

Photographs

There are a total of 25 Photographs in the archive. Of these, 15 are wartime photographs, 14 feature Churchill, 10 are original press or military photographs with original captions and/or wet stamps, and 6 feature Barker. Size of the photographs ranges from 11.75 x 8.5 inches (29.8 x 21.6 cm) to 2.5 x 2.5 inches (6.4 x 6.4 cm, a set of 5 photographs still in their original Kodak folder with Barker’s name written thereon by the developer).

At least 9 of the photographs are of Churchill or his wife, Clementine, with other world leaders (including U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Chinese President Chiang Kai-Shek, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, Eleanor Roosevelt, and British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden) at wartime conferences with world leaders, including the 1944 Quebec Conference and 1945 Crimea (Yalta) Conference. Among the images are also dozens of seniorAllied military and civilian figures.

Mementos

There are 12 items we categorize loosely as mementos.

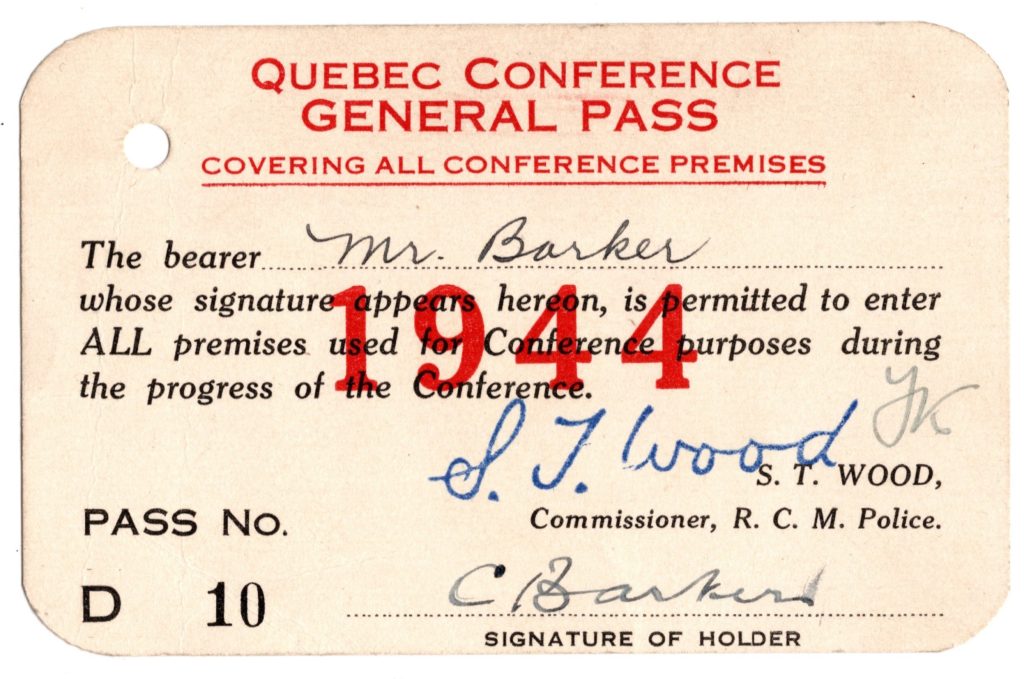

Barker saved his two original, personal, numbered passes to the 1944 Quebec Conference attended by Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Mackenzie King. One of these two passes, impressively printed in red and black and signed by both Barker and the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, is Barker’s “Quebec Conference GENERAL PASS COVERING ALL CONFERENCE PREMISES”. There are also copies of Barker’s numbered “ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE PERMIT” specifying that it was valid “7 JUL 1945 until 7 OCT 45” for AEF OP AREA including GERMANY”.

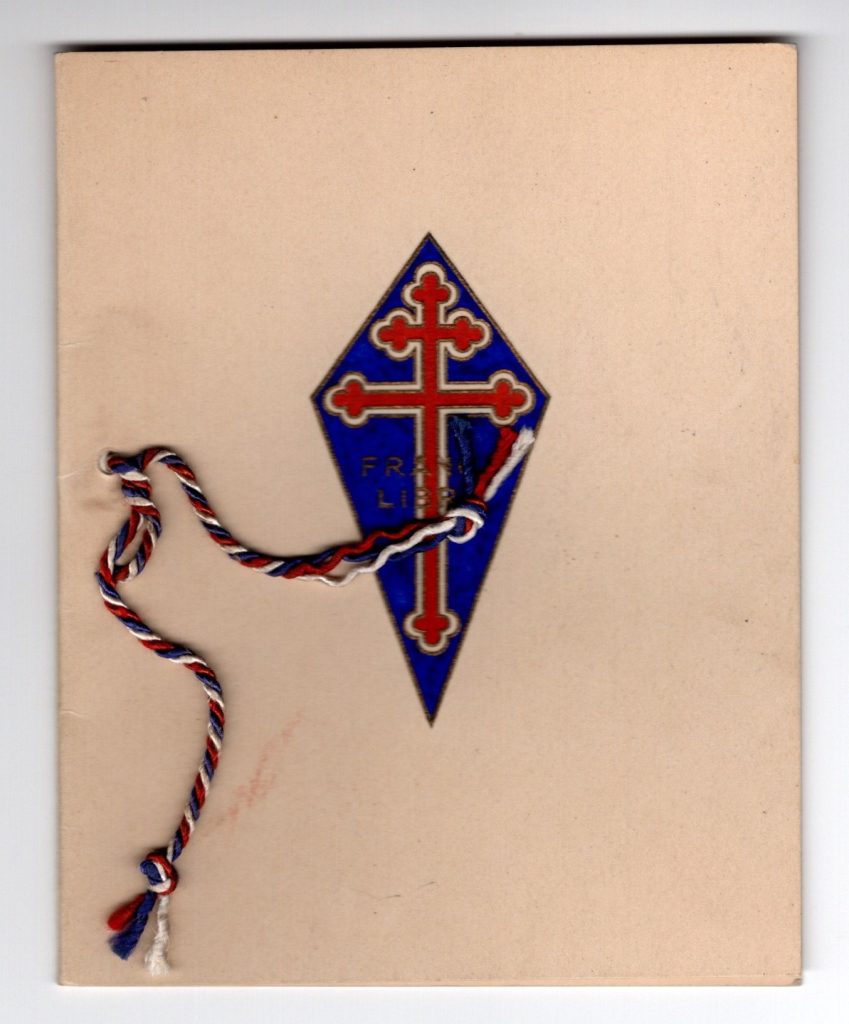

An intriguing, elaborate, deliciously ironic wartime holiday card from “France Libre” (The political entity headed by Charles de Gaulle that, during the War, claimed to be the legitimate government of France). The card is printed on the front with a tricolor France Libre device, bound in tri-color string, and within features a photograph of a rather silly looking French seaman blowing a bunting-festooned horn and wearing a France Libre device. The card’s interior is printed “Meilleurs voeux pour Noel la Nouvelle Annee” and hand-emended with the valediction “Bien Favoise”. Certainly Barker and his colleagues must have truly appreciated the “Free French” contribution to the war effort – a conspicuously fancy holiday card. There is also the irony that Churchill had been forced in 1940 to order the sinking of the French fleet by the British Navy at Mers-El-Kebir, owing to the fact that said French fleet chose to bravely resist their ally, Britain, rather than the Nazis who had invaded and occupied their country.

Still another elaborate holiday card is from the “British Embassy Dakar”. There are other Africa mementos – a 1958 invoice and receipt for “Barker & party” from “Andy’s Look-Out Hotel” in Plettenberg Bay, South Africa and a printed advertisement card of “Sheppards Hotel” in Fort Victoria (now Masvingo), Zimbabwe.

We note a curious typed list including English artists, architects, and dates, terminating in some notes on how and when silver items were hallmarked per the London Assay Office. We speculate that this relates to Barker’s noted expertise in old silver.

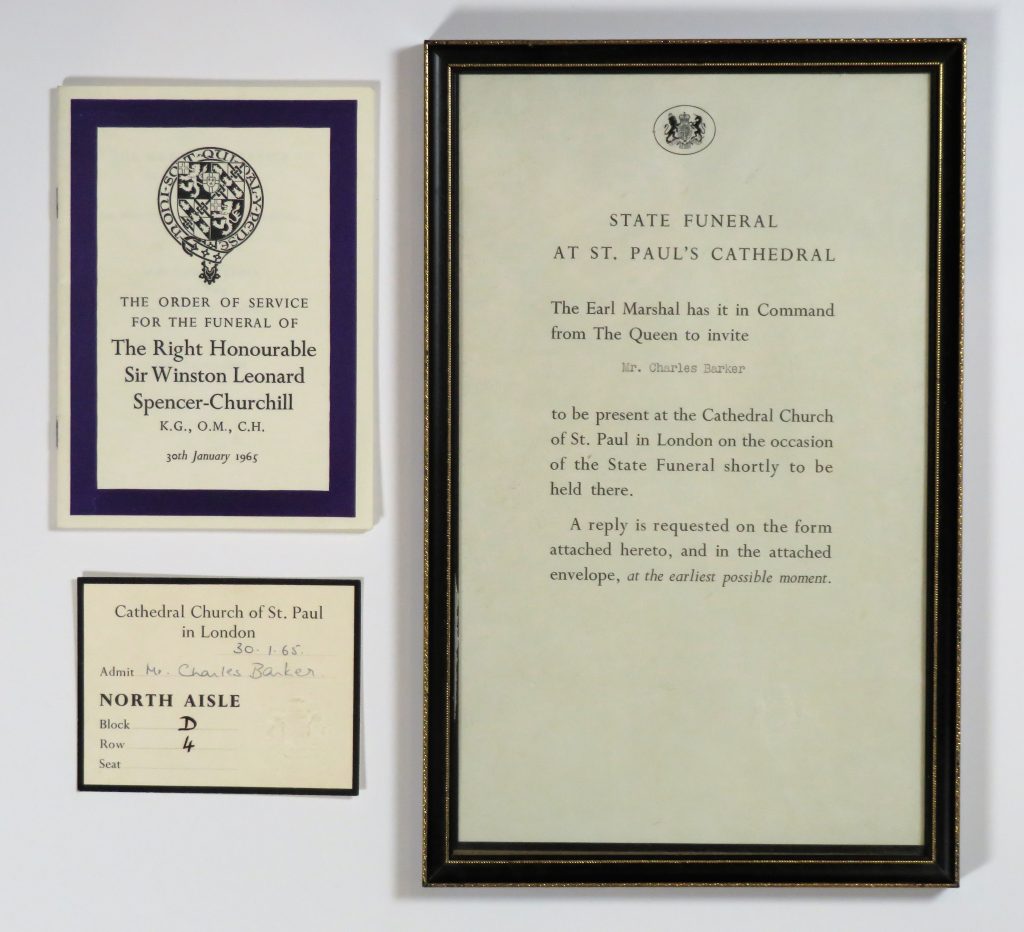

Last but not least, punctuating both the archive and Barker’s long association with Churchill, are Barker’s documents from Churchill’s 30 January 1965 state funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Barker’s personal invitation to the funeral is framed and accompanied by Barker’s St. Paul’s seating ticket, as well as two booklets provided to funeral attendees – The Order of Service for the Funeral of The Right Honourable Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill and the Ceremonial to be Observed at the Funeral.

The final item in the binder is Major Alan Taylor-Smith’s notes on Charles Barker and the provenance of this archive, printed on four A4 sheets.

It has been a delight to spend some time with the artifacts in this archive, appreciating the glimpses the voices, perspectives, and moments they encapsulate, and communicating some of what we found with you.

Cheers!