If you are an antiquarian bookseller, then no physical object is just an object. Each item we handle, however mundane it may physically appear, encapsulates, represents, preserves, or conveys something greater than just the sum of its physical attributes.

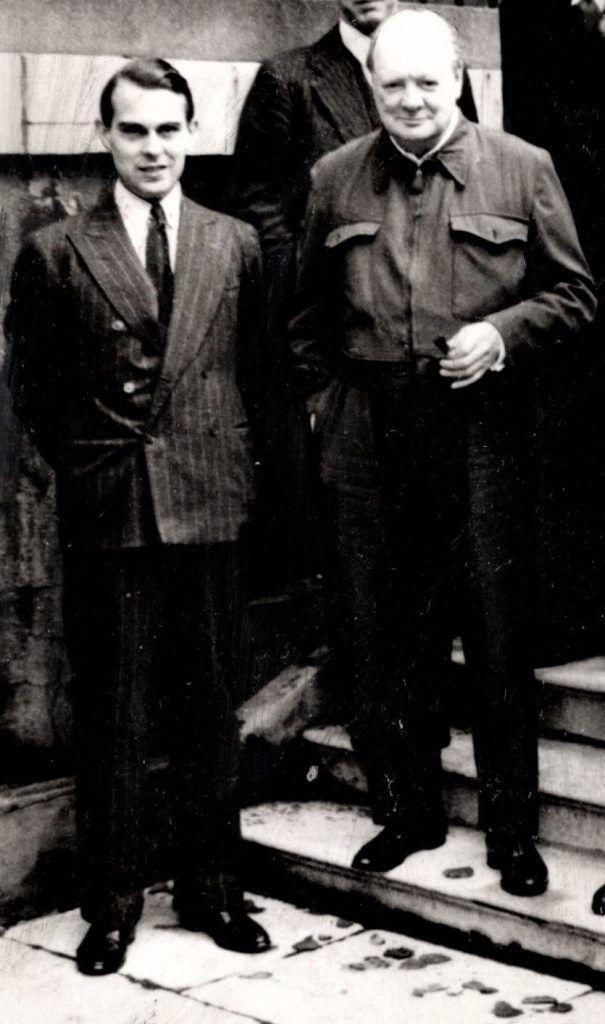

Take, for example, four old typed sheets, pasted on some blue notepaper. These humble sheets are a proverbial front row seat to one of the most gifted orators in recorded history and a physical artifact of the Second World War. They are also a connection not only to Winston Churchill in the early days of his wartime premiership, but also to a man who closely, long, and loyally served and observed Churchill.

The Object

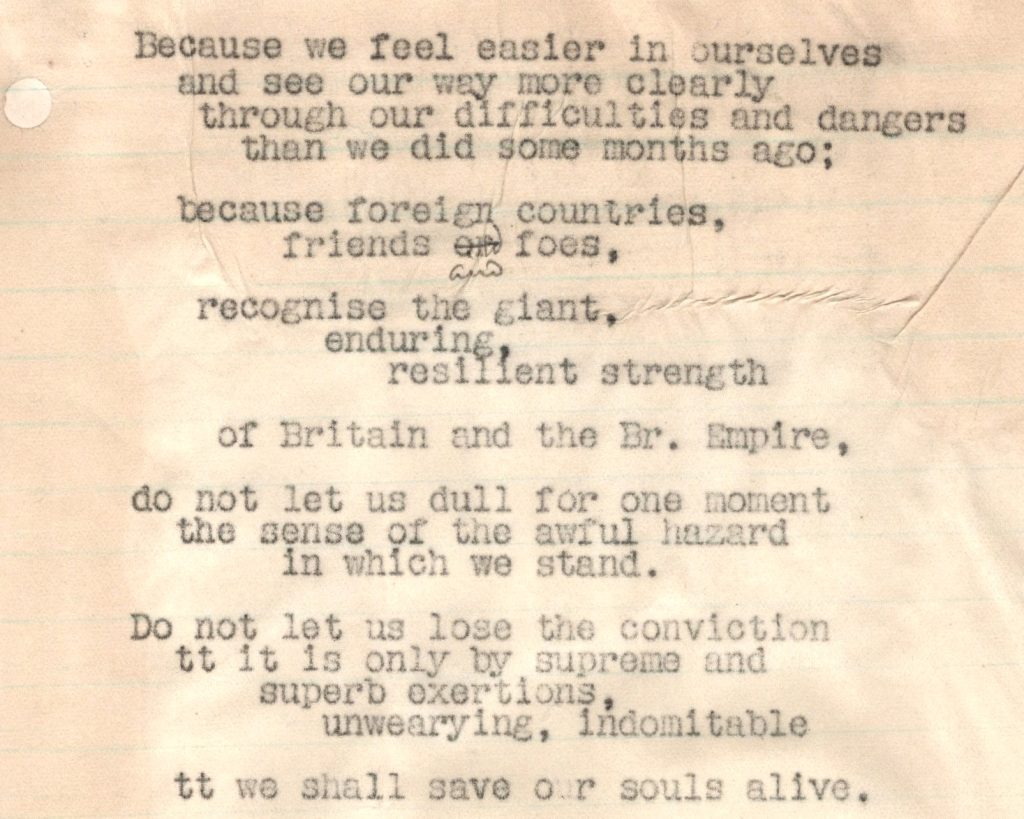

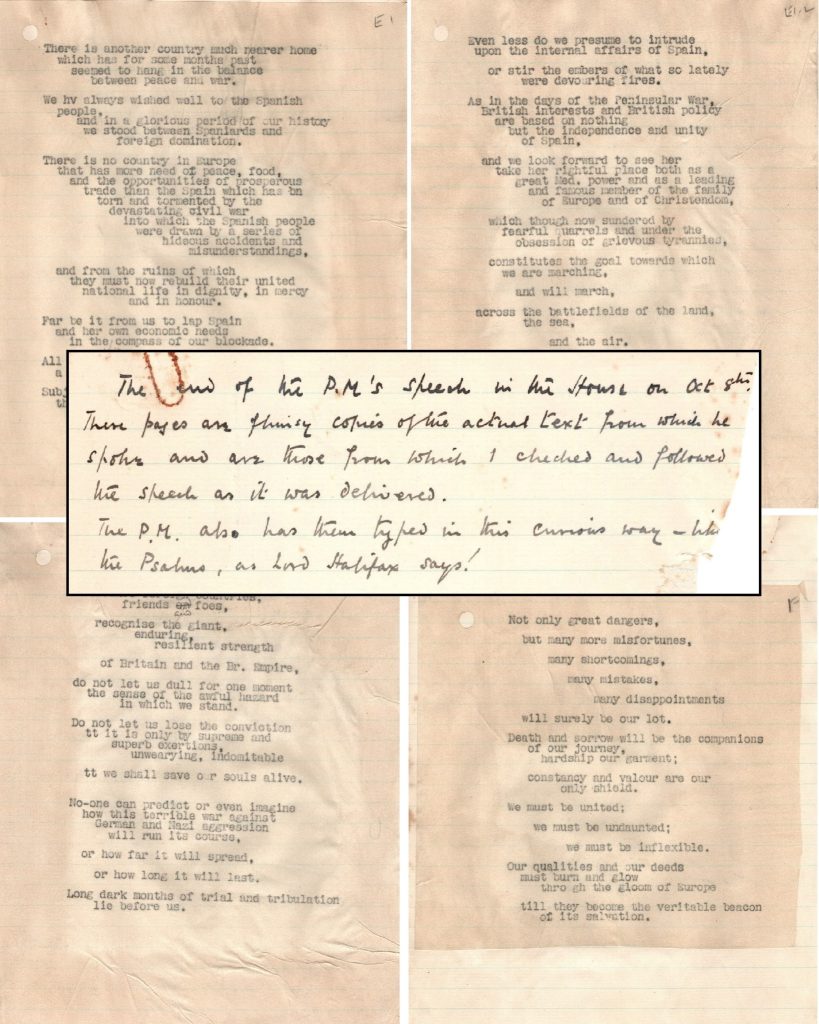

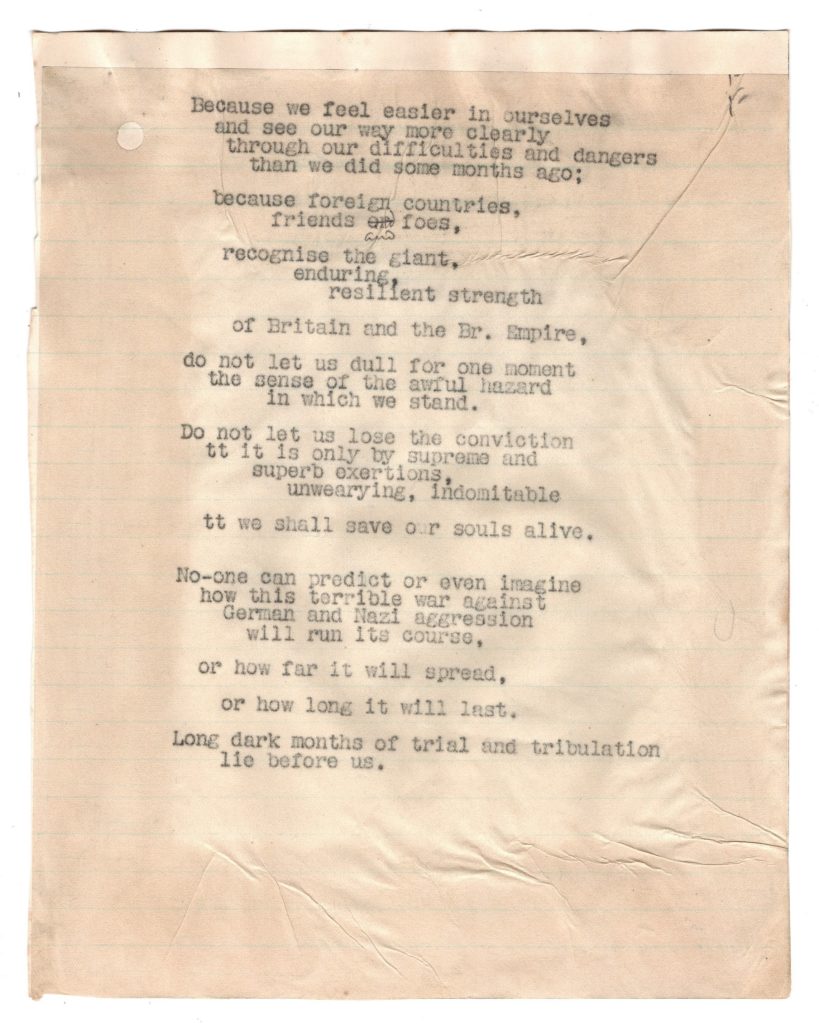

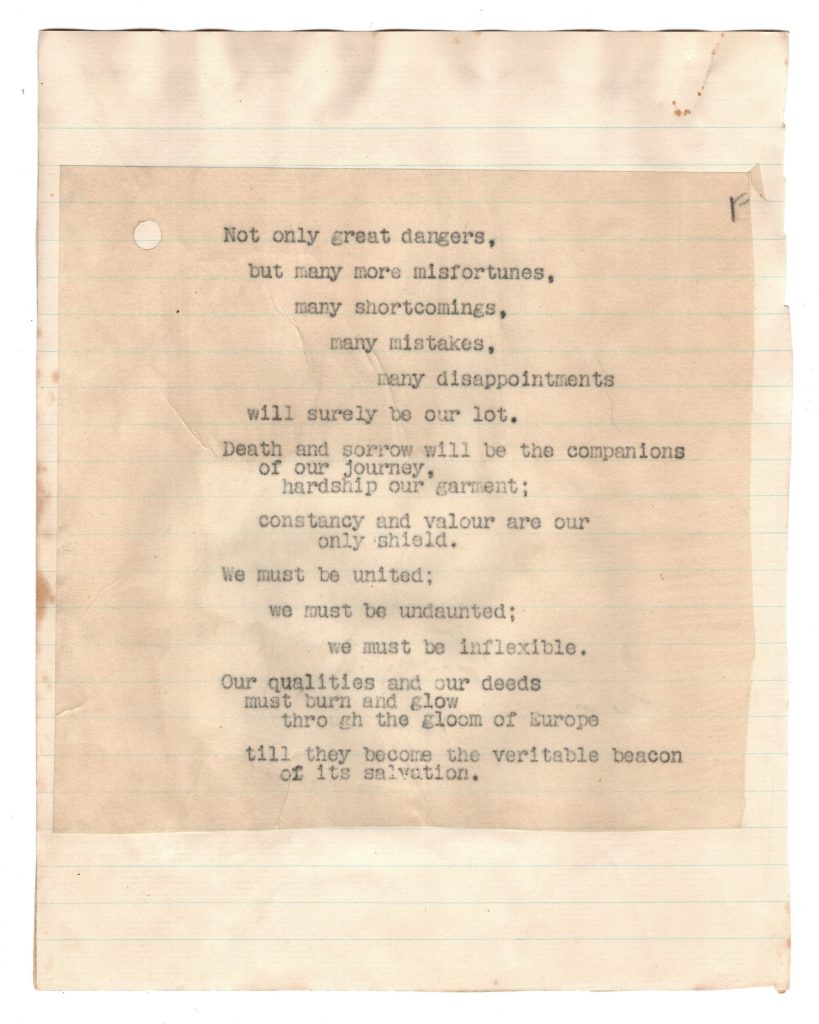

These sheets are the final paragraphs of Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill’s 8 October 1940 speech to the British House of Commons, typed and hand-emended on four pages in Churchill’s distinctive ‘psalm form’, along with a manuscript note from Churchill’s Private Secretary, John Rupert “Jock” Colville, explaining the origin and use of these pages.

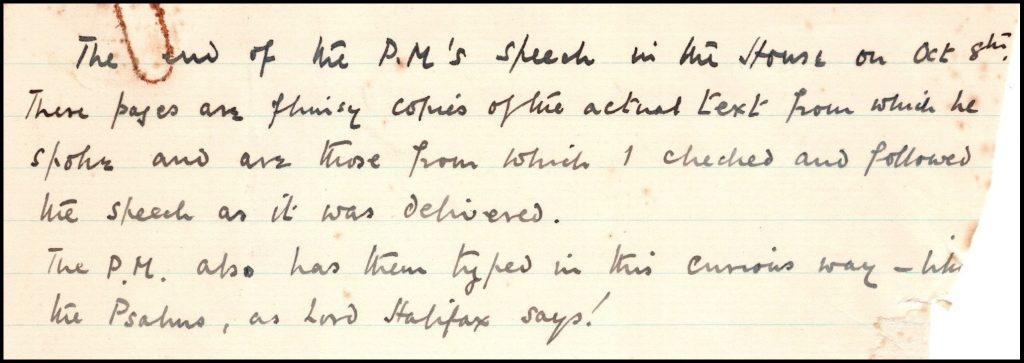

Four typed sheets are pasted on to the recto and verso of blue-ruled notepaper. In his own hand, filling the first six lines of an additional sheet of blue-ruled note paper, Colville provides both explanation and provenance: “The end of the P.M.’s speech in the House on Oct 8th. | These pages are flimsy copies of the actual text from which he | spoke and are those from which I checked and followed | the speech as it was delivered. | The P.M. also has them typed in this curious way – like | the Psalms, as Lord Halifax says!”

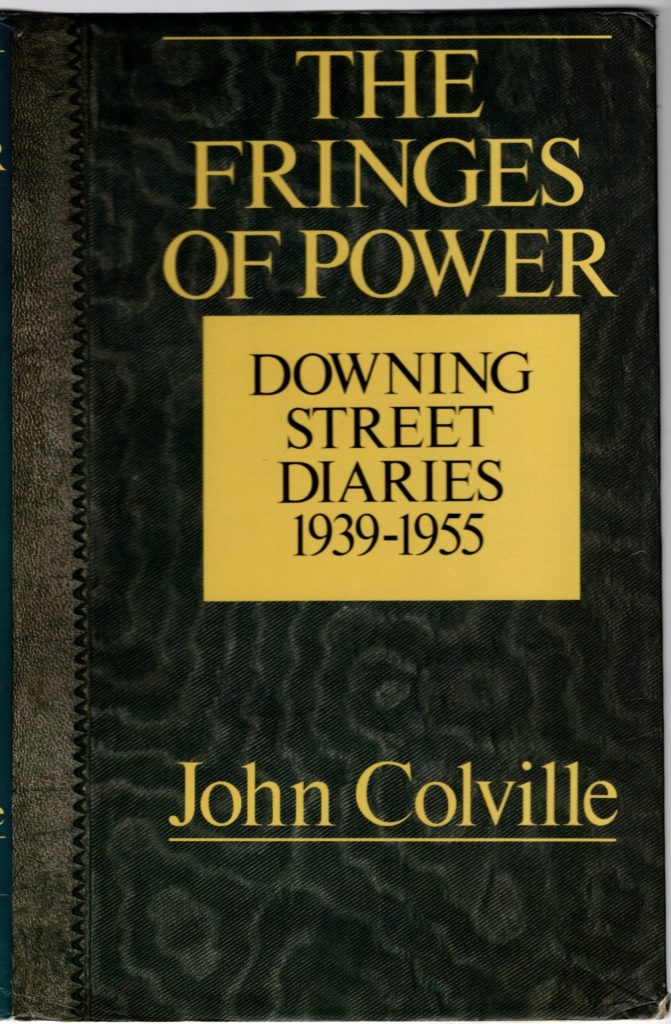

The “Tuesday, October 8th” entry in Colville’s diary, published many years later, refers to these very notes: “I followed the speech from a flimsy of the P.M.’s notes, which are typed in a way which Halifax says is like the printing of the psalms.” (The Fringes of Power, Downing Street Diaries 1939-1955, p.258)

Of course, Churchill’s speech has been reprinted many times in many volumes and can readily be read off not only myriad printed pages, but also off of any screen after a moment’s quick search of the internet. But you experience something entirely different when reading Churchill’s words thus, looking over Colville’s spectral shoulder, holding the same pages he held, and mouthing the words as you imagine listening to them as they were actually delivered by Churchill in the House of Commons on 8 October 1940.

Colville’s confirmation that Halifax coined the term for the layout of Churchill’s speeches (allegedly because it reminded the pious Halifax of lines from the Book of Psalms) is a delicious bit of irony. Halifax had been Neville Chamberlain’s Foreign Secretary and an architect of the failed policy to appease Hitler. It was Halifax’s unwillingness to succeed Chamberlain that cleared the way for Churchill to become Prime Minister; Halifax instead became Churchill’s ambassador to America. Halifax’s “psalm” observation is no accident of liturgical linguistics; the church-going, fox-hunting, politically adept aristocrat was given the nickname “The Holy Fox” by none other than Churchill.

Churchill’s speeches were not only typed out in ‘psalm form’ but then “hole-punched with a tool Churchill called ‘Klop,’ named for the noise it made…” so that they could be “fastened with a… short piece of yarn with metal bars at each end, which allowed him to flop from sheet to sheet…” (Langworth, The Churchill Project)

The four sheets are hole-punched at the upper left. Consonant with Colville’s note that these pages “are those from which I checked and followed the speech as it was delivered”, there are two minor emendations.

Colville’s explanatory note shows loss and scarring along the right edge and a paperclip stain to the upper left. The typed speech sheets remain as originally glued to the note paper, with some attendant original wrinkling. They are marked in pencil at the upper right “E” and “F” respectively.

The Moment

On 8 October 1940, Britain and her Prime Minister were suffering the dire consequences of appeasement. The four pages of Churchill’s speech, comprising the final, two-paragraph peroration, encapsulate the state of Britain in October 1940, beleaguered, alone, and enduring the sustained air assault by Hitler’s Luftwaffe that would become known to history as the Battle of Britain.

The day Colville held these notes while he listened to his boss deliver the words in the House of Commons, he arrived for work at No. 10 Downing Street and “found everybody crouching in the shelter because bombs had fallen in the Horse Guards Parade and on the War Office.” There was no forgetting that London was under attack, even at comparative ease in the waning hours of the day. Colville recorded that in the evening, after the speech, Churchill “was in great form – as always after a speech has been successfully achieved – and amused [Anthony] Eden and me very much by his conversation with Nelson, the black cat, whom he chided for being afraid of the guns and unworthy of the name he bore. ‘Try and remember,’ he said to Nelson reprovingly, ‘what those boys in the R.A.F. are doing.” A year later, Colville would be one of “those boys in the R.A.F.” but that night he spent like the rest of his fellow Londoners, beneath the bombs, recording of his sleep “The air in the shelter went wrong in the middle of the night and I almost stifled.”

Churchill’ speech was long. He spoke of homes destroyed in the Blitz, and of personally visiting the destruction, showing his gift for encapsulating and projecting British resilience: “I have never been treated with so much kindness as by the people who have suffered most. One would think one had brought some great benefit to them, instead of the blood and tears, the toil and sweat which is all I have ever promised.” Churchill resisted calls for in-kind reprisals on Germany, insisting that only military targets should be attacked. Churchill also spoke of U.S. aid to Britain and addressed press criticism of Britain’s recent Dakar expedition.

He also spoke of Spain, which is where the four pages of Colville’s copy of Churchill’s speech notes begin. In his closing, Churchill strikes a characteristic tone – boldly defiant, lyrically inspiring, and soberly realistic all at once.

“Because we feel easier in ourselves

and see our way more clearly

through our difficulties and dangers

than we did some months ago;

because foreign countries,

friends or and foes,

recognise the giant,

enduring,

resilient strength

of Britan and the Br. Empire,

do not let us dull for one moment

the sense of the awful hazard

in which we stand.

Do not let us lose the conviction

tt it is only by supreme and

superb exertions,

unwearying, indomitable

tt we shall save our souls alive.

No-one can predict or even imagine

how this terrible war against

German and Nazi aggression

will run its course,

or how far it will spread,

or how long it will last.

Long dark months of trial and tribulation

lie before us.

Not only great dangers,

but many more misfortunes,

many shortcomings,

many mistakes,

many disappointments

will surely be our lot.

Death and sorrow will be the companions

of our journey,

hardship our garment;

constancy and valour are our

only shield.

We must be united;

we must be undaunted;

we must be inflexible.

Our qualities and our deeds

must burn and glow

through the gloom of Europe

till they become the veritable beacon

of its salvation.”

Colville himself noted that this peroration “was eloquently spoken and enthusiastically received.”

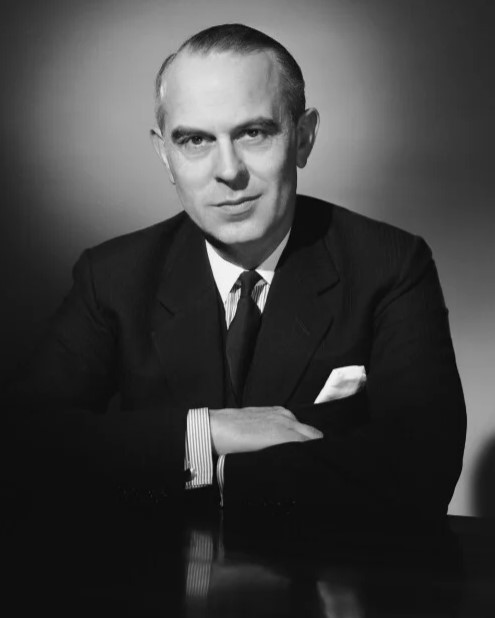

Jock Colville

The Second World War was only a month old when, on 3 October 1939, a brilliant 24-year-old civil servant in the Foreign Office was appointed Assistant Private Secretary to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Seven months later, when wartime leadership famously passed to Winston Churchill, Sir John Rupert Colville (1915-1987) began working for Churchill. Colville would remain “almost constantly at Winston’s side” for the majority of Churchill’s two premierships (May 1940-July 1945 and October 1951-April 1955).

Colville’s 10 Downing Street service to Churchill was interrupted only by Colville’s active service as an RAF pilot between October 1941 and December 1943. Apart from Colville’s official contributions to history, we are obliged to him for his defiance; although it was forbidden under wartime regulations, Colville kept meticulous diaries that he locked nightly into his 10 Downing Street desk. Significant excerpts from this diary were eventually published in 1985, self-deprecatingly titled The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries 1939-1955. Colville’s diaries continue, even now, to illuminate Churchill’s wartime leadership. Most recently, New York Times bestselling author Eric Larson relied heavily on Colville’s diaries in writing The Splendid and the Vile (2020), his novelized take on the first year of Churchill’s wartime Premiership.

Of course, Colville did more than observe and record. On 8 October 1940, after following the speech from these very notes, “John Peck and I corrected the official report and altered the text in many places to improve the style and the grammar; for the P.M.’s speeches are essentially oratorical masterpieces and in speaking he inserts much that sounds well and reads badly.”

Colville’s compulsive will to write, his position at the epicenter of action, Churchill’s deep confidence in him, and his keen and discerning intellect render Colville’s diaries a significant contribution to the known history of Churchill and his time. In the interwar years, Colville served as Private Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II (while she was still Princess Elizabeth) and married one of her ladies-in-waiting. Colville raised funds for the establishment of Churchill College, Cambridge (where his diaries now reside), and was eventually a trustee of both Winston’s and Lady Churchill’s estates.

Colville was knighted in 1974, having previously been awarded the Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1955, and the Companion of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO) in 1949.

Cheers!