Florence Vivienne Entwistle, nee Mellish (1889-1982) first photographed Winston S. Churchill sometime between late December 1949 and early February 1950. Her journey to both photography and the Churchill family was intriguingly oblique.

She had trained and performed as a singer. Upon marriage to the artist Ernest Entwistle, she took up a successful career as a miniaturist. Her photographic career did not begin until 1934, when, midway through her forties, she began assisting her husband and son, Antony Beauchamp, with photography. When Antony set up his own studio, she did the same, adopting the name “Vivienne”, photographing an array of public personalities, including five successive prime ministers.

Vivienne’s relationship with the Churchills had a rocky start. On 18 October 1949, the Churchills’ daughter, Sarah, married Antony. Winston and Clementine “learned of the marriage… from the newspapers” and were “greatly upset… particularly Clementine, who took it very hard indeed.” Nonetheless, on 19 December 1949 Winston and Clementine visited Antony’s mother, Vivienne, in her studio and on 20 December Clementine wrote to Sarah “We have made friends with Antony’s father and mother and we had an agreeable luncheon together.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, p.496)

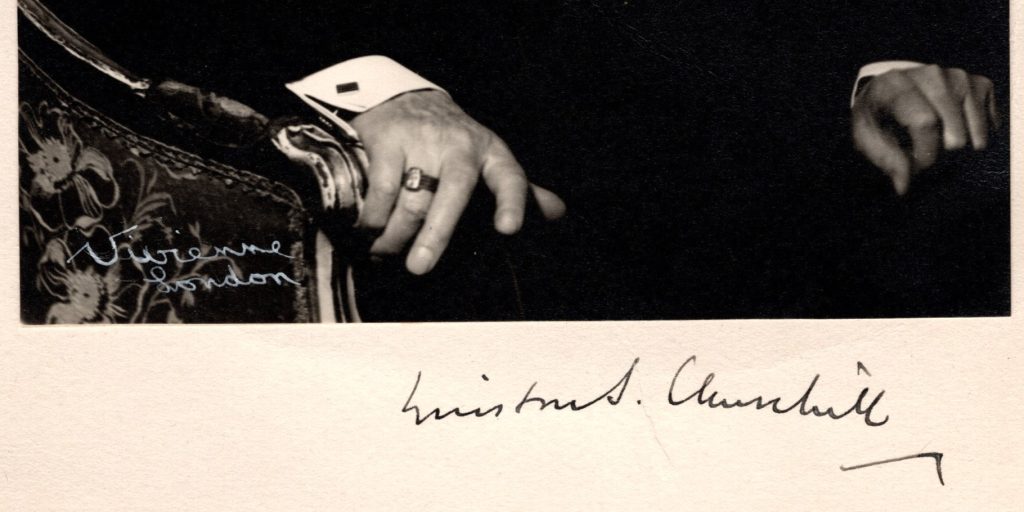

It was then, or very soon thereafter, that Vivienne made her best-known image of Winston Churchill. It may have been captured when Churchill first visited Vivienne’s studio in December 1949. Given that it was used in a campaign publication for the February 1950 General Election (see Cohen A247.2), it was taken no later than early 1950. We can also be certain that it was captured in Vivienne’s studio; Vivienne was known for requiring her subjects to come to her. Indeed, Vivienne’s autobiography is titled They Came to My Studio (1956) and this very image of Winston graces the dust jacket. Vivienne recalls (p.16) that this iconic and often reproduced image was the last of their photo session, the product of Churchill agreeing to give her “only one more minute” after he had already risen to go.

The relationship with the Churchills became familial. Vivienne “is possibly the only photographer to have had the privilege of photographing the entire Churchill family.” Vivienne eventually made exceptions to her in-studio rule for the Churchills. The National Portrait Gallery holds 214 of Vivienne’s portraits, including her most famous one of Winston (NPG x45168) and fourteen others of Winston, Clementine, and their grandchildren, the majority of which were taken at the Churchills’ country home, Chartwell.

We have the good fortune to currently offer three signed Vivienne portraits of the Churchills, all of which have a story to tell beyond just the general improbability of having been captured by the mother of the man who maritally absconded with their daughter.

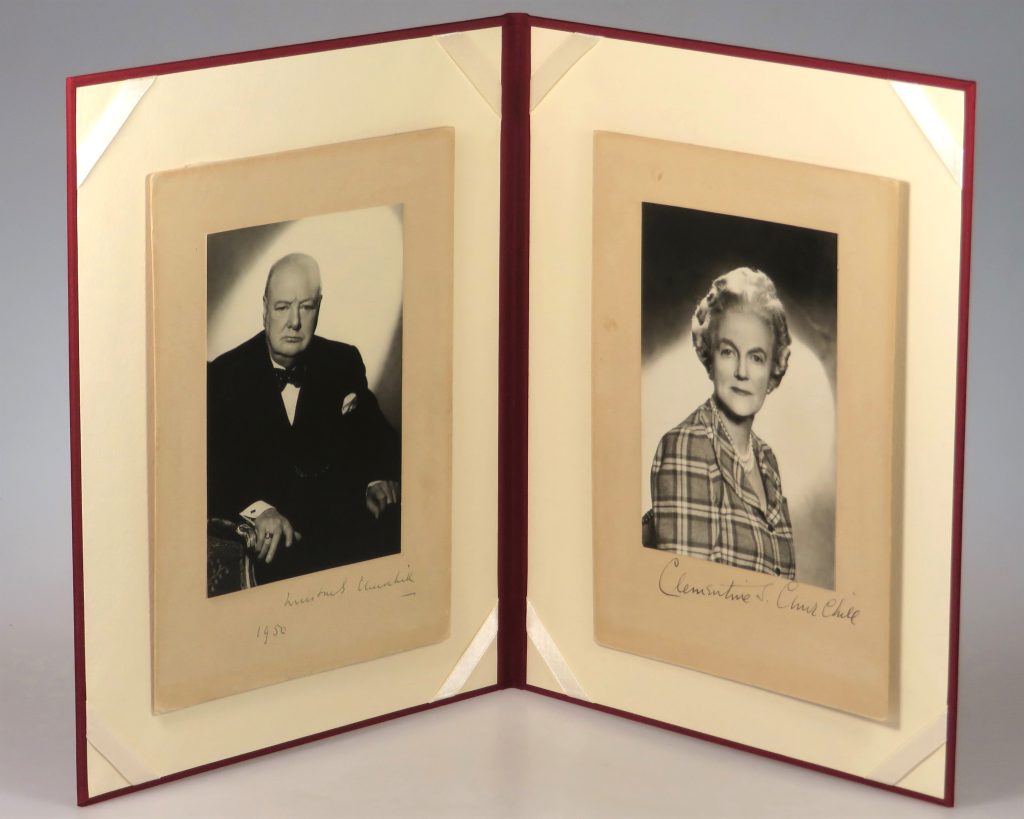

Our first offering is a pair – one of Winston and one of Clementine – each signed, respectively by Winston and Clementine. Significantly, Winston’s print is not only signed, but dated in his hand “1950”.

The date is significant; widely used during his second and final premiership (1951-1955), this portrait is often mistakenly dated to 1951, even by the National Portrait Gallery. A date of “1950” in Churchill’s own hand rather decisively settles the issue. Of the image of Clementine (p.28), Vivienne recalls “I was proud when Lady Churchill came to me, because she so rarely consents to go to a studio. I believe she came – as she does so many things – for her husband’s sake.”

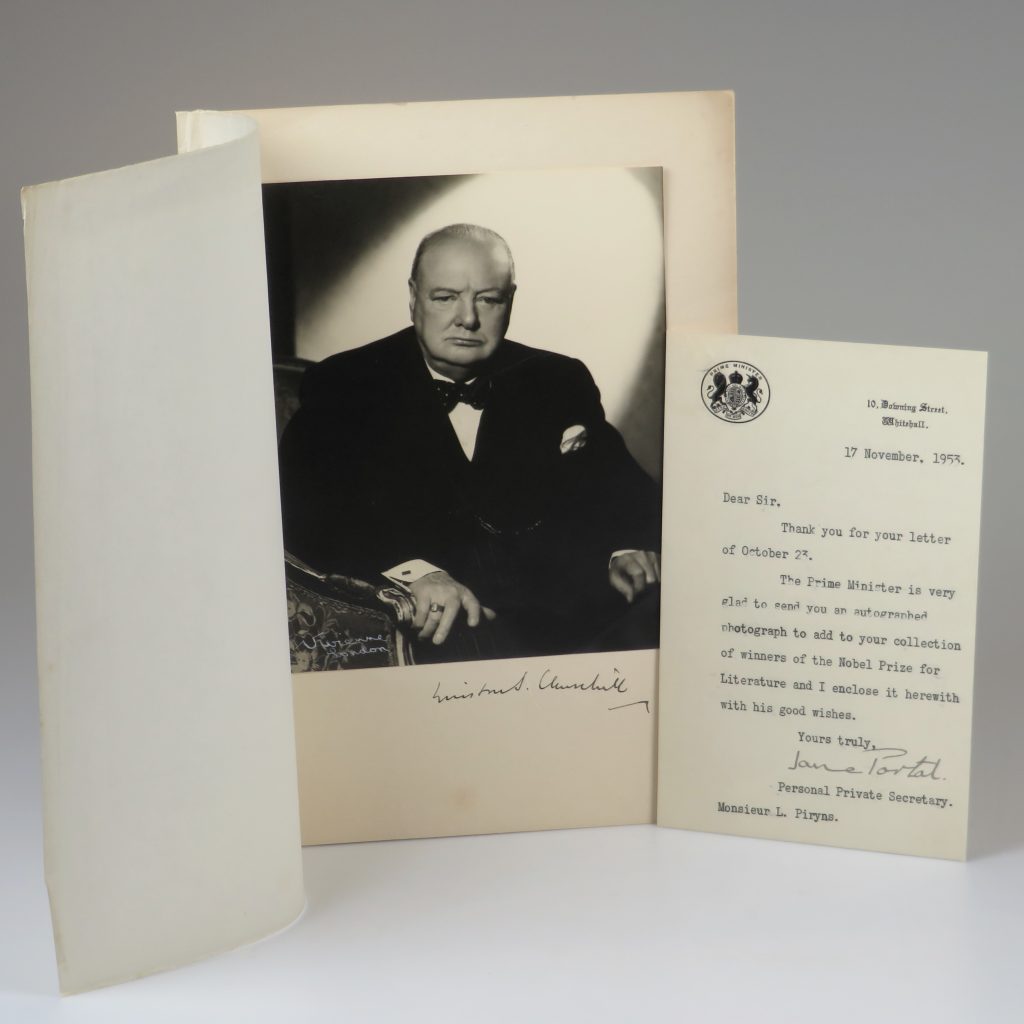

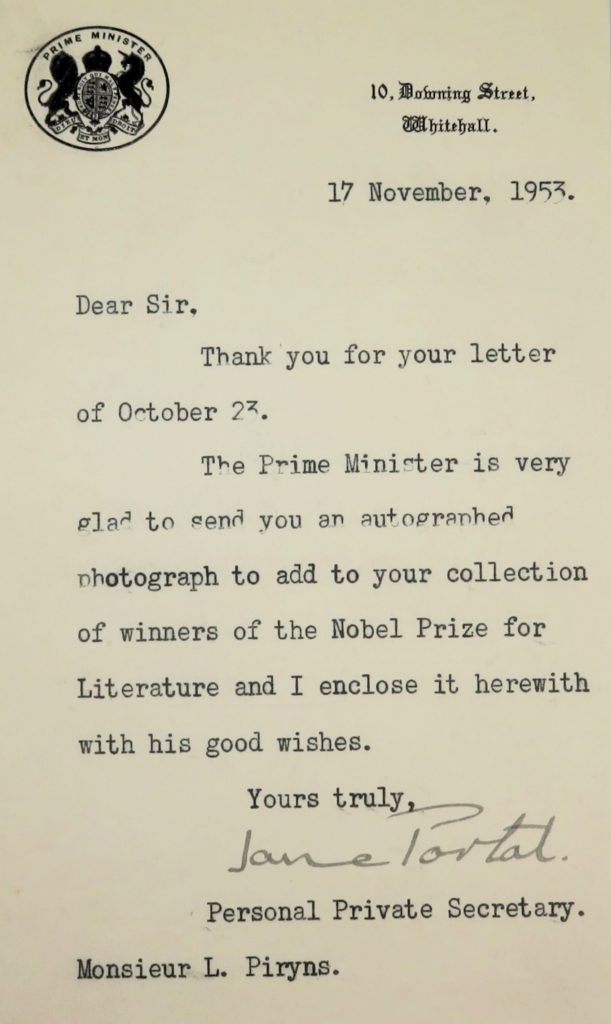

Our second offering is another Vivienne studio print of Churchill, but this one signed by both Churchill and Vivienne, and accompanied by a 17 November 1953 presentation letter signed by Churchill’s personal private secretary. This double-signed studio print was a gift to a collector upon the occasion of Churchill being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Notably, the fact that Churchill would receive the award had been announced only a month prior, on 13 October 1953, and the award ceremony did not take place until 10 December 1953. So this collector was demonstrably eager and swift in both requesting and receiving this signed photograph.

But, in our opinion, the accompanying presentation letter from Jane Portal suggests the more compelling story – one that renders the minor scandal of Sarah and Antony’s marriage quite tame by comparison.

Jane Williams nee Portal, Lady Williams of Elvel (1929-2023) “was the niece of both Air Chief Marshal Charles ‘Peter’ Portal and of ‘Rab’ Butler, who served as president of the board of education in Churchill’s wartime coalition government and as chancellor of the exchequer when Churchill returned to power in 1951.” (Stelzer, Working With Winston, p.222) “It was “Uncle Rab” who told his niece in December 1949 that Churchill was looking to hire a new secretary and suggested that she apply.” (Freeman, ICS, 16 July 2023) Portal worked for Churchill from December 1949, when he was still Leader of the Opposition, until April 1955, when he resigned his second and final premiership.

Why Portal left turns out to be quite the story, which took years to be told. Churchill had asked Portal to continue working for him, but Portal left Churchill’s service anyway. Ostensibly, she left to elope with Gavin Welby, from whom she was later divorced. “In 1975, Portal married Charles Williams, Baron Williams of Elvel. Her long life “extended just far enough to enable her to watch her son Justin Welby the Archbishop of Canterbury, crown King Charles III in Westminster Abbey”. (Freeman, ICS, 16 July 2023) But in later years it was discovered – and disclosed by Lady Williams – that her son, the Archbishop, was the issue of an affair immediately preceding her first marriage with another Churchill staffer, Montague Browne. Browne remained in Churchill’s service almost continuously until Churchill’s death in 1965.

All of which is to say that this is why we love doing what we do. Sure, a little bit because these portraits of Winston and Clementine provide indirect testimony to the intriguingly dramatic, sometimes scandalous, and occasionally even salacious web of relationships appended to the long public life of Winston Churchill. But, more broadly and much more significantly, because of how physical artifacts can viscerally connect us to lives long ago spent in an ever-receding past.

A decade before Vivienne captured her portrait of Winston, in November 1940 the newly minted wartime Prime Minister told the House of Commons: “History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.” Each object we handle, if we are able to discover and tell its story, steadies and brightens the lamp.

Cheers!