Double standards are enjoying something of a renaissance. These days, they are being vigorously applied to formerly powerful and respected men, who are retroactively diminished by contemporary standards. For women, there is nothing new about double standards.

Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman (1920-1997) has been called “The last courtesan.” This is a polite euphemism for the cruder implications. She has also been called “Ambassador” by presidents and “daughter” by The Winston S. Churchill and “mother” by another. Whatever may be said of her – and judgements abound – Pamela was indubitably Churchillian in her resourcefulness, her determination to define herself, and her will to engage the world.

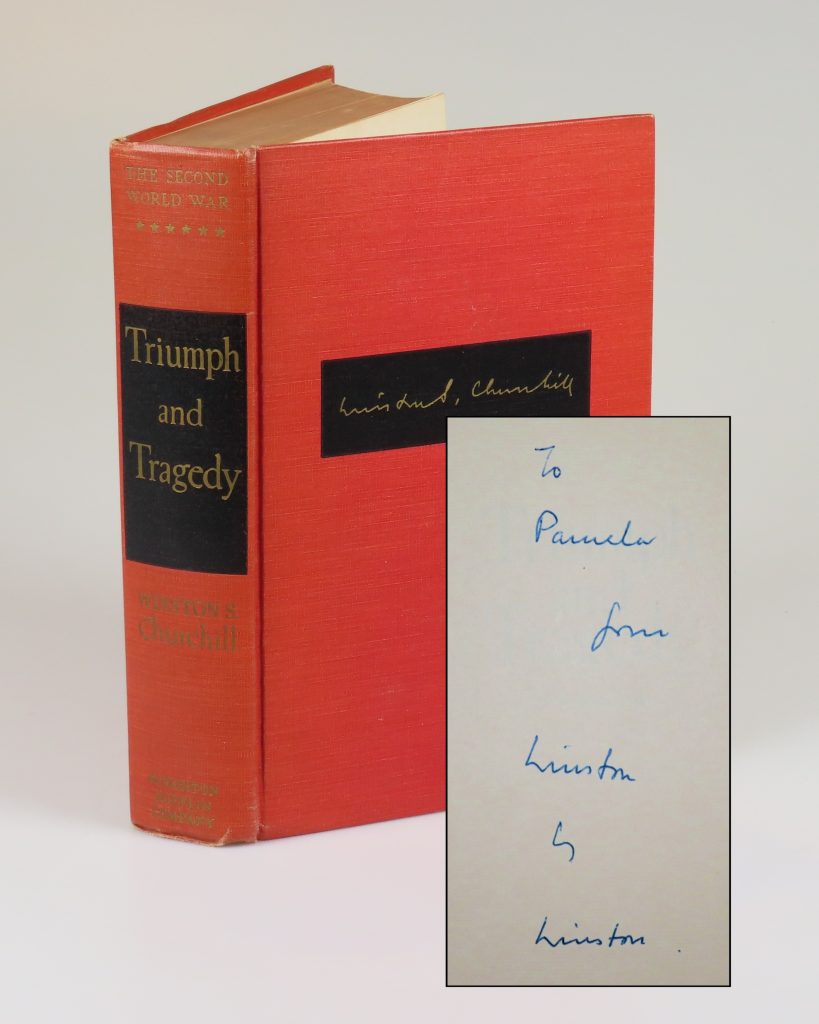

Our post about Pamela is prompted by our recent acquisition of a remarkable book inscribed to her – the first edition of the sixth and final volume of Winston Churchill’s history of the Second World War, inscribed by Churchill to his former daughter-in-law.

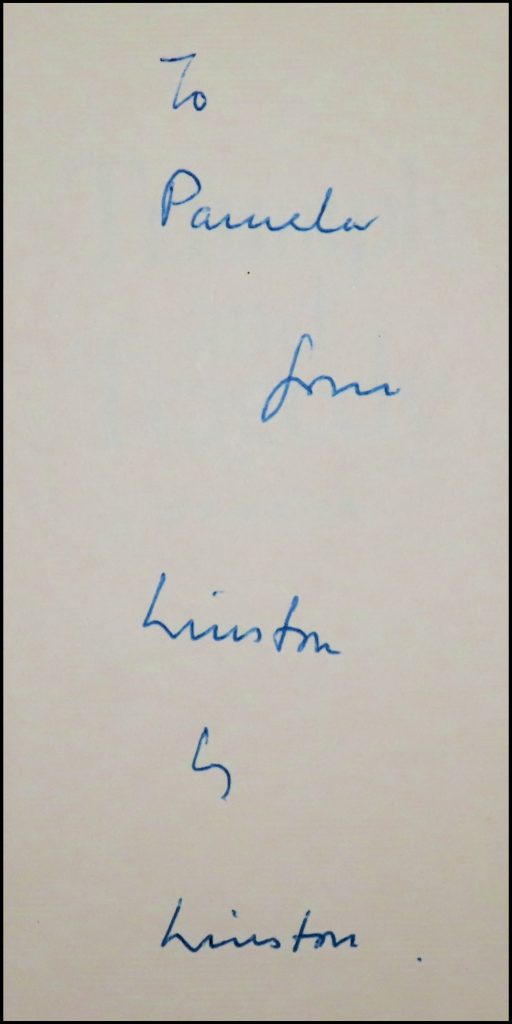

The notably warm, playful inscription is inked in blue in six lines on the front free endpaper recto: “To | Pamela | from | Winston | by | Winston”. This book is offered for sale HERE on our website.

On 4 October 1939, at the beginning of the Second World War, 19-year-old Pamela married Randolph S. Churchill, the only son of Winston S. Churchill. Two years later, five months into Winston S. Churchill’s storied wartime premiership, she gave birth to his namesake grandson on 10 May 1940. By the time Churchill inscribed this volume to Pamela, she had long since divorced his son and was busy making a life for herself that would center on her own choices and involve a great many “great” men, as well as a few more surnames.

Born in England as Pamela Beryl Digby, she eventually became a naturalized citizen of the United States and ended her career, and life, as America’s Ambassador to France. When she married Randolph, Pamela had already “developed the charm and social skills for which she would become well known.” There was, however, more to her than charm; an indication of her intrepid nature could perhaps be gleaned from her horseback riding.

“Problems surfaced in the wartime union from the beginning, some perhaps attributable to Pamela’s own inclinations, but quite certainly attributable to Randolph’s “drinking, carousing, gambling, and generally boorish behavior.” Nonetheless, Pamela developed a strong bond with her father-in-law.” Certainly, part of that bond was Winston’s namesake grandson. Upon meeting Churchill in January 1941, President Roosevelt’s trusted advisor, Harry Hopkins, recalled “he showed me with obvious pride the photographs of his beautiful daughter-in-law and grandchild.”

While her husband served abroad and soused, Pamela had wartime affairs – notably with Averell Harriman, President Roosevelt’s envoy to England. “After Averell Harriman left England, Pamela began an affair with Edward R. Murrow, the CBS war correspondent, and also had a fling with his boss, CBS founder William Paley.” But not all of her connections were affairs; through Winston she met the publishing magnate Max Beaverbrook, who hired her as a reporter.

Divorce, a move to Paris, and more noteworthy affairs, mostly with prominent, married men, followed the war. These included Elie de Rothschild and the wealthy Italian businessman Gianni Agnelli, for whom she converted to Catholicism. Certainly, there was no shortage of affairs, but Pamela was also “cultivating friendships that she could use to her benefit later.” One of her lovers, Broadway producer Leland Hayward, divorced and, in May 1960, became Pamela’s second husband. In the years that followed, Pamela “made connections in both Hollywood and New York” and became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

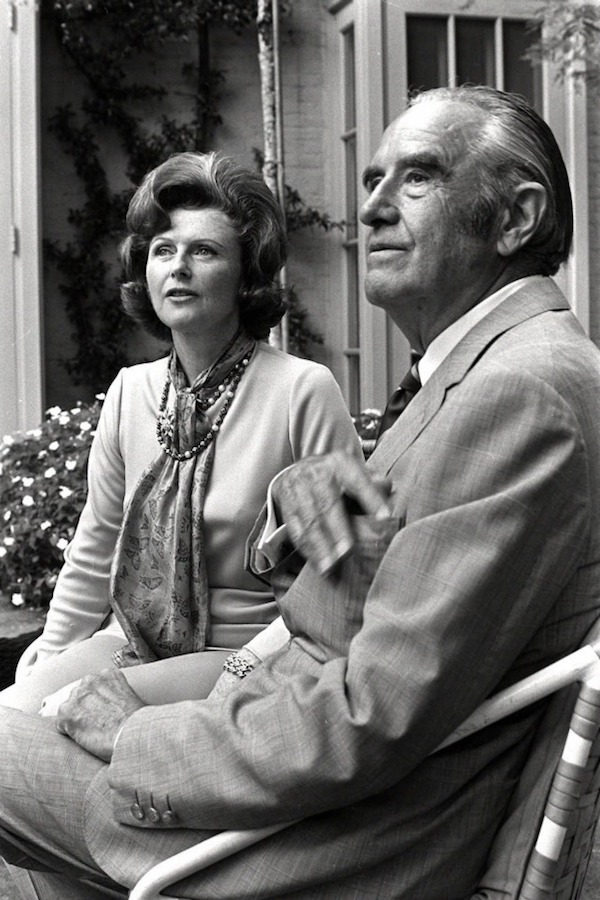

After Hayward died, Pamela married her former paramour, Averell Harriman, “then seventy-nine, who had served as governor of New York and had run as a Democratic presidential candidate.” Pamela threw herself into Democratic Party fundraising and king-making, eventually supporting the presidential aspirations of Bill Clinton, who in turn appointed Pamela U.S. Ambassador to France. Pamela served from 1993 to 1997, dying in Paris just a few months before her planned retirement. “Her memorial service at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C, deemed by the New York Times the ‘closest thing to a state funeral Washington has seen in years,’ was attended by more than 1,200, including President Clinton.

“Russell Baker of the New York Times compared Pamela Harriman’s life story to ‘one of those bad novels in which women with gumption to spare come from nowhere and make the world their private property.’ The fact that she was able to succeed in this manner was to him wonderful, however, ‘because the world’s deck is so heavily stacked against real women’ (9 Feb. 1997). Today the great strength of the ‘real woman’ is generally not deemed to lie in the ability to seduce rich and powerful men to her advantage, but in the 1940s and 1950s the opportunities for ambitious women to succeed in public life were limited.”

Cheers!

References: Sonia Purnell; Martin Gilbert; ANB; The Times; New York Times