In late 1919, T. E. Lawrence was still fifteen-and-a-half years away from his untimely death. That summer, Lawrence had taken the first steps to realizing his pre-WWI ambition to set up a private press with an Oxford Friend by purchasing a property on the edge of Epping Forest. Only months before, he had begun the famously long and tortuous process of writing his account of the Arab Revolt, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. He was only beginning to realize that the rest of his life would not be the retired and retiring printer of books, but would instead be defined by his First World War role in Arabia.

The context is important for the letter Lawrence wrote on 21 November 1919 to an admirer who apparently requested his autograph. The admirer was reportedly a Boy Scout who also solicited autographs from Victoria cross winners, eventually amassing a significant collection.

Lawrence’s letter is noteworthy for a number of reasons. For being signed with his surname “Lawrence” rather than the “Shaw” surname he would soon assume and use for the rest of his life. For capturing Lawrence on the cusp of the fame he would spend the rest of his famously short life struggling to reconcile and reject. And for explicitly mentioning the man who was making a fortune by making Lawrence uncomfortably famous even as this letter was being written.

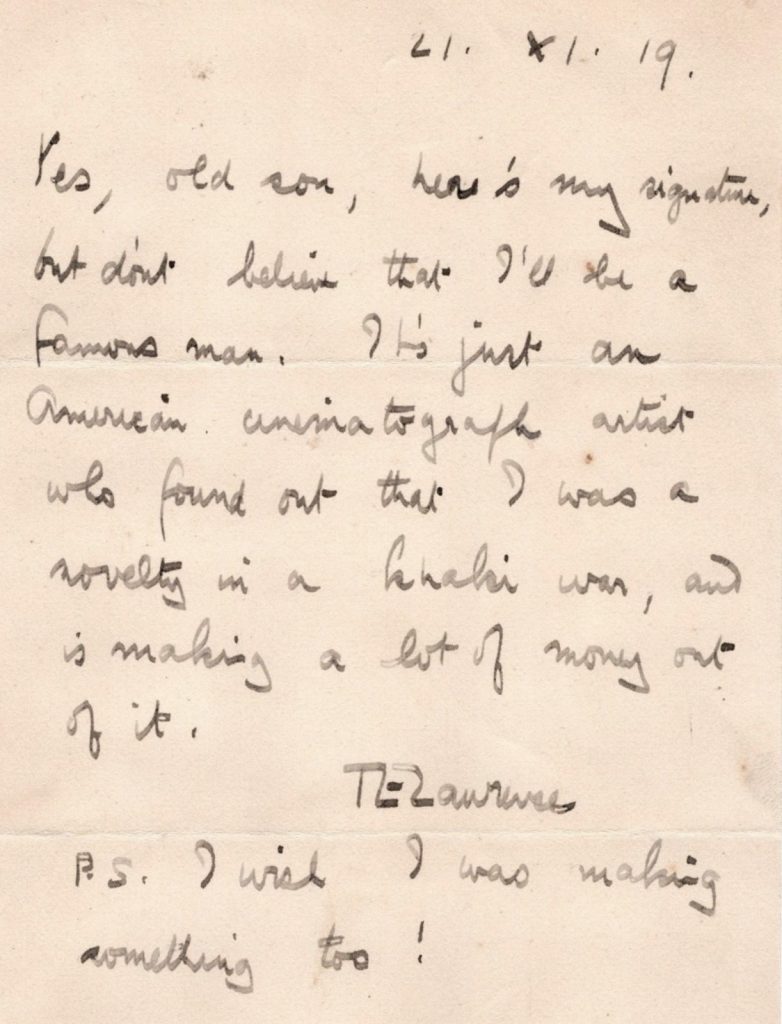

Lawrence was no stickler for stationery, and would write on almost anything; we once discovered an unpublished letter from him written on the back of an RAF “Application for Mechanical Transport”! Characteristic of Lawrence, this letter is on an unadorned, undistinguished sheet of wove paper measuring 7 x 4.5 inches (17.8 x 11.4 cm), which shows evidence of having been trimmed along the left edge (notionally before Lawrence penned his missive). In eleven lines in Lawrence’s hand in black ink on one side of the sheet, he wrote:

21. XI. 19 | Yes, old son, here’s my signature, | but don’t believe that I’ll be a | famous man. It’s just an | American cinematograph artist | who found out that I was a | novelty in a Fehalai [sic] war, and | is making a lot of money out | of it. | T E Lawrence | P.S. I wish I was making something too!”

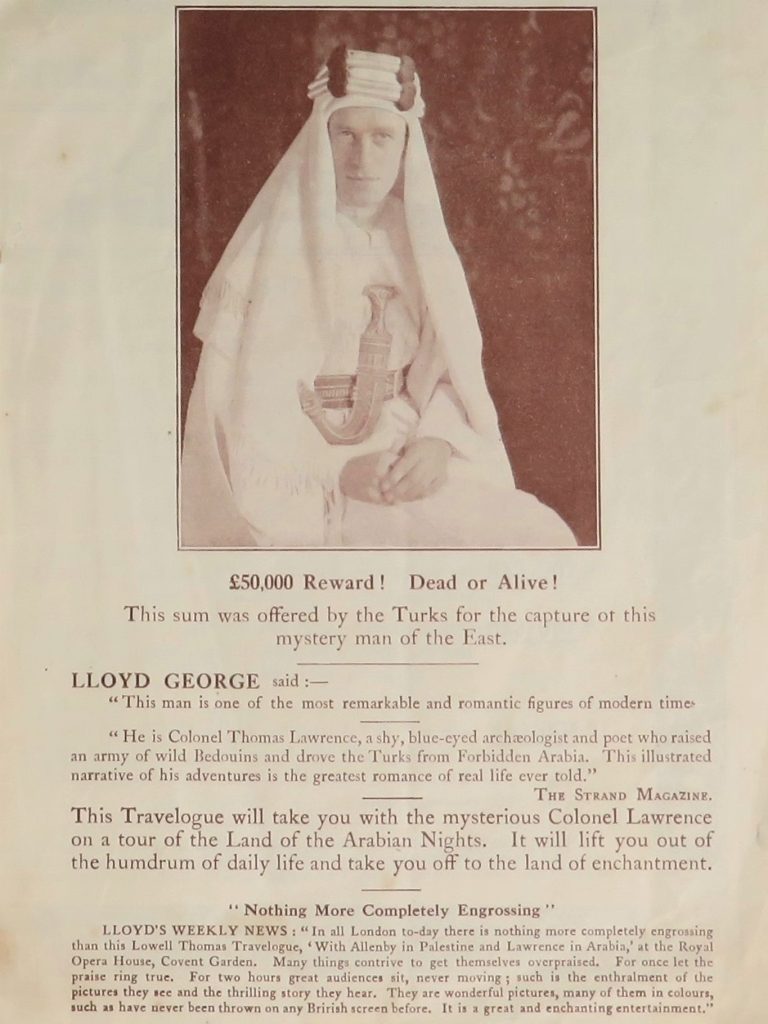

T. E. Lawrence’s (1888-1935) remarkable odyssey as instigator, organizer, hero, and tragic figure of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War transformed him from an eccentric junior intelligence officer into “Lawrence of Arabia.” But that would not have happened without “an American cinematograph artist”.

By late 1919, then 31-year-old Lawrence had experienced the failure of the Paris Peace Conference to achieve the security and sovereignty he had sought for Prince Feisal and his Arab compatriots. “Lawrence was affected deeply by his sudden political isolation and the failure to win a better settlement for Feisal… By the autumn… the strain had taken its toll… By a supreme irony, while Lawrence was trying to come to terms with the failure in Paris, London audiences were being treated to a romanticized version of his wartime career…” (Wilson, Lawrence of Arabia, pp.621-2)

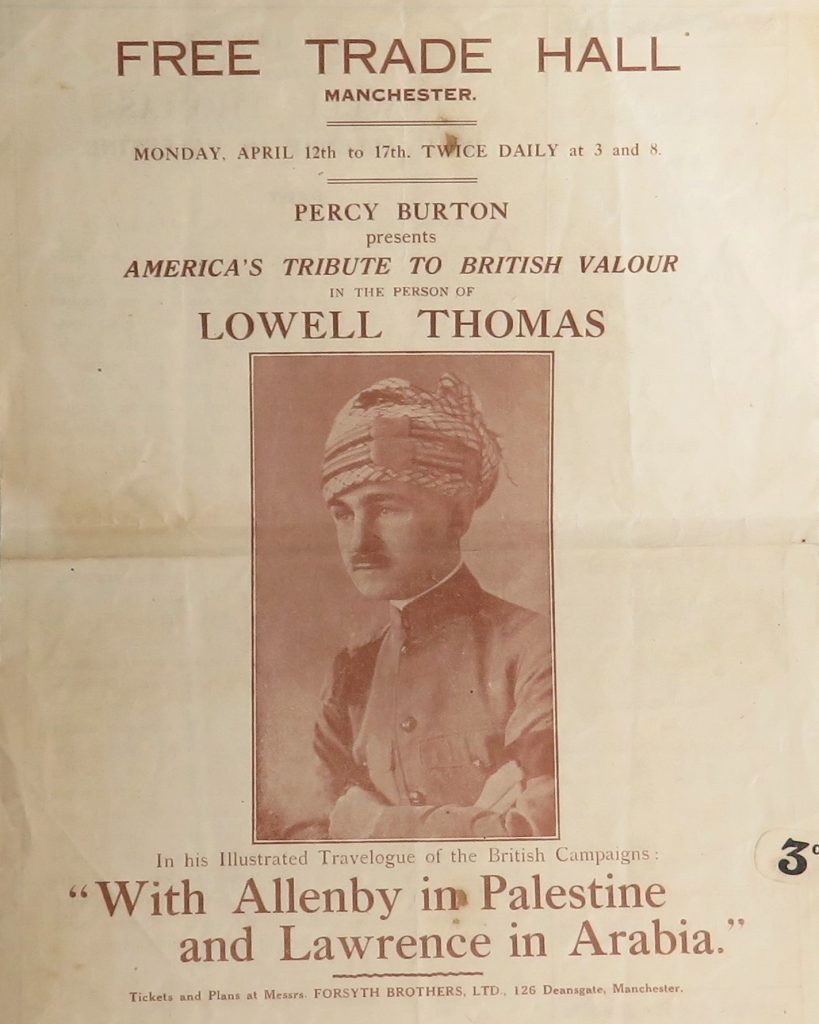

This was the result of the relentless – and relentlessly effective – promotional efforts of Lowell Thomas (1892-1981). In 1917, when the United States entered the First World War, Lowell Thomas and his cameraman Harry Chase (1883-1935) were sent to Europe to find stories that would build American public support for the war. The Western Front understandably failed to inspire, so Thomas embarked for Palestine, drawn by Allenby’s campaign to wrest Jerusalem from the Ottomans.

Jerusalem had been under Muslim control since the crusaders were ejected in 1187. “For Britain the fall of Jerusalem was a notable propaganda coup…” (ODNB) Likewise, Allenby was a coup for Thomas, who would have a hand in Allenby’s subsequent portrayal “as a modern-day Richard Lionheart”. (Punch, 19 Dec 1917) Already preloaded with literary and religious associations, Palestine and the holy city of Jerusalem, along with its liberators, was the story Thomas was seeking. But there was a bigger prize than Allenby and Jerusalem, where, in early 1918, Lowell Thomas also met T.E. Lawrence (1888-1935), who consented to let Thomas capture him in photographs and on film.

This proved fateful. While Allenby became a Field Marshal, his officer, T. E. Lawrence, surpassed all military rank, propelled into legend.

Returning to America, Thomas began giving popular lectures on the war in Palestine, replete with dramatic film and images he and Chase had captured. Thomas was invited to take his lecture and film extravaganza to Britain and, in August 1919 – just a few months before Lawrence wrote this letter – began a tremendously successful run at Covent Garden. Thomas thereafter also toured England. Gradually, the show that had begun as “With Allenby in Palestine” evolved to “and Lawrence in Arabia” or “And Colonel Lawrence in Arabia”. Eventually Lawrence achieved top billing and became simply “of Arabia”. He has remained thus for more than a century.

Lawrence’s feelings about the resulting fame were famously complicated. Even this short letter is revealing. Lawrence’s personal courage and commitment to the cause of the Arab Revolt are beyond dispute. And yet in this letter he belittles both himself and his Arab comrades-in-arms, saying “I was a novelty in a Fehalai war…” Lawrence’s misspelling does not conceal the sentiment; fellah (plural fellaha) is a peasant in Arabic-speaking countries – hardly a fulsome portrayal. Lawrence also twice mentions money – both that Thomas “…is making a lot of money…” and his wish that he, Lawrence, “…was making something too!” In a contemporary letter, Lawrence wrote of Thomas’s promotions “They are… making life very difficult for me, as I have neither the money nor the wish to maintain my constant character as the mountebank he makes me.” (Wilson, p.625)

Lawrence’s biographer said of him that, in 1919, “One consequence of this sudden fame was that Lawrence began to receive large numbers of unsolicited letters… Understandably he wanted none of this, and he replied to few of the letters.” (Wilson, p.626) Fortunately, Lawrence did reply to some, as evidenced by this letter; we cannot know what prompted Lawrence in this specific case, but we do not need to know in order to appreciate both that he did, and that his reply has survived.

Lowell Thomas’s glamorous and romantic image of Lawrence permanently alloyed with the man and his accomplishments. In the years after he wrote this letter, Lawrence would work with Winston Churchill to achieve a settlement that kept faith with the Arabs for whom he had fought. Lawrence would write, destroy, rewrite, suppress, and endlessly fret his written account of the Arab Revolt. Lawrence would even change his surname to “Shaw” and enlist in the RAF in an attempt to distance himself from the indelible celebrity thrust upon him by “an American cinematograph artist”. Nonetheless, he would become and remain “Lawrence of Arabia”. This letter is an artifact of the earliest days of that indelible, inexorable fame.

Click HERE to browse our entire inventory of material by and about T. E. Lawrence.

Cheers!

One thought on ““…don’t believe that I’ll be a famous man.” A letter from T. E. Lawrence on the cusp of his becoming indelibly “of Arabia””