I mean no disrespect to some of the fine actresses who have earned the distinction, but whatever my daughter (yes, an intended audience for this post) chooses to become in life, I hope it is not a “Best Supporting Actress.” As we were cataloguing a Winston Churchill letter from 1945 this week, it occurred to me that “Best Supporting Actress” might be the worst award ever. Yet, for most of history, and even still in a lot of places in the world, it feels like “thanks for helping me look good” was the most recognition women could expect. Which brings me to Ava Courtenay Anderson, formerly Ava Wigram, nee Bodley, and eventually Viscountess Waverly (1895-1974) – an extraordinary woman I’d never have known about if not for her first husband, Ralph Wigram, and her friend, Winston Churchill. Another potential female Atlas relegated to “supporting.”

And the Best Supporting Actress Award goes to…

After her parents’ 1908 divorce, Ava lived chiefly in Paris with her father, “who made certain she was formidably well read, had a deep respect for culture and literature, and a very retentive memory.” This training and education coupled with “self confidence and… good looks” made her a complementary partner to the man she married in 1925. Ralph Follet Wigram (1890-1936) was a “talented but shy diplomatist,” then “a high-flyer” in the British embassy Paris. Ava “soon established an influential social circle, despite her anxieties about Wigram whose health was permanently impaired from 1927 by an attack of polio and about their only child, Charles, born severely disabled in 1929.”

When Wigram was recalled to London in 1933, their diplomatic partnership took on global implications. In 1933, future Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill was out of power and out of favor, his growing concern about the rise of Nazi Germany at odds with both the British government and prevailing public sentiment. Ava and Ralph shared Churchill’s concerns, and in 1934 Ralph began supplying Churchill with secret government information, including about German rearmament, for Churchill to use to harry the Government and rouse the public.

This image, taken by Ava, captures her husband and Churchill at Chartwell in 1935.

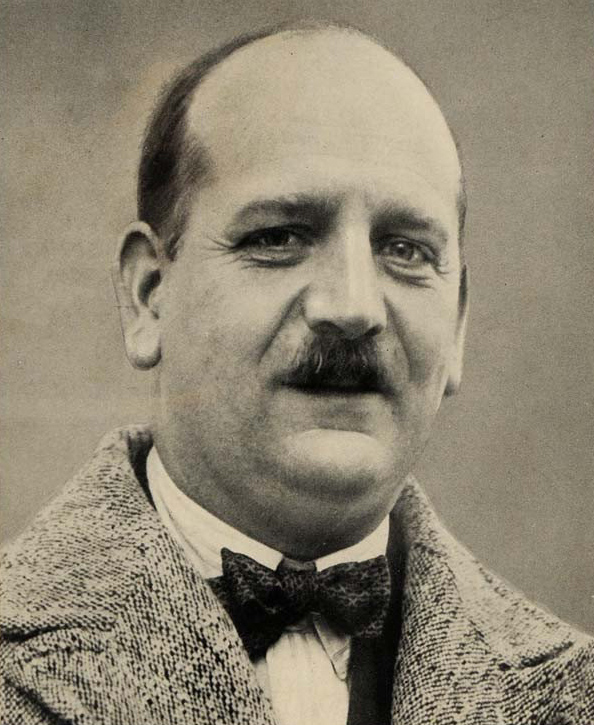

Enter Pierre Etienne Flandin

The apex of Ralph’s and Ava’s efforts came in March 1936.

On 7 March 1936, Nazi Germany’s troops reoccupied the Rhineland, in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. It was a test of British and French resolve. A few had the foresight to understand that this was the last, least costly opportunity to stop Hitler before war became an inevitability. Those few included Ava, Ralph, Winston, and the French Foreign Minister, Pierre Etienne Flandin (1889-1958), who had briefly served as France’s prime minister from November 1934 to June 1935.

In March 1936, Flandin visited London to attempt to galvanize British support for decisive, immediate, combined Franco-British action to resist Hitler’s aggression. There he found staunch allies Ralph and Ava Wigram.

Wigram “thought it was within the compass of his duty to bring Flandin in touch with everyone he would think of… from the press, and from the Government…” to hear Flandin’s exhortations. The Wigrams hosted meetings – and even a press conference – with Flandin at their London home. The British Government steadfastly refused to act, summed by Lord Lothian’s cavalier dismissal of Nazi ambitions: “After all, they are only going into their own back-garden.”

Terrible vindication and a trial

In the aftermath, things went poorly for the Wigrams, for Churchill, and for Flandin.

Ralph Wigram took the failures of the French and British governments deeply personally and died, suddenly, in December 1936. Churchill, who attended his funeral and gave a luncheon at Chartwell for the mourners, praised Wigram’s “profound comprehension” and regarded his “untimely death” an “irreparable loss”.

Churchill remained largely politically impotent for the rest of the decade, cursed like a proverbial Cassandra with the ability to see what was coming, but not to alter the course of events. Only the terrible vindication of the outbreak of the Second World War returned Churchill to the Government in September 1939 as First Lord of the Admiralty. He became beleaguered Britain’s wartime prime minister in May 1940.

After Ralph Wigram’s death, Churchill reported that Ava was bereft and “all adrift now. She cherished [Wigram] and kept him alive. He was her contact with gt. affairs.” Now she was a widow with a severely disabled son. Nonetheless, “Ava was able to carry on… opposition to Nazism and to flourish as a hostess at her home, 4 Lord North Street, Westminster, near parliament and Whitehall. Playing to her strengths as an informed and well-connected society figure, she created an environment valued by many senior diplomats and politicians.” That was how she met Sir John Anderson (1882-1958), who became her second husband in October 1941, during the Second World War. More on that later.

The horror of the Second World War they had tried to prevent at least provided some measure of vindication and renewal for Ava and Winston. It ruined Flandin. In June 1936, shortly after his failed effort in London, he lost his post as French Foreign Minister. Drawing perhaps the wrong lesson after the Munich concessions to Hitler in 1938, Flandin expressed support for appeasement. After France’s subjugation by Nazi Germany, collaborationist Vichy chief of State Phillipe Petain appointed Flandin Foreign Minister and Vice-Premier on 13 December 1940. Flandin occupied those positions only until 9 February 1941. Despite his extraordinary mid-1930s efforts to stop Hitler, Flandin was arrested and imprisoned by DeGaulle during the war, and after the war tried by the retrospectively-righteous French.

Oh, right, there was a letter…

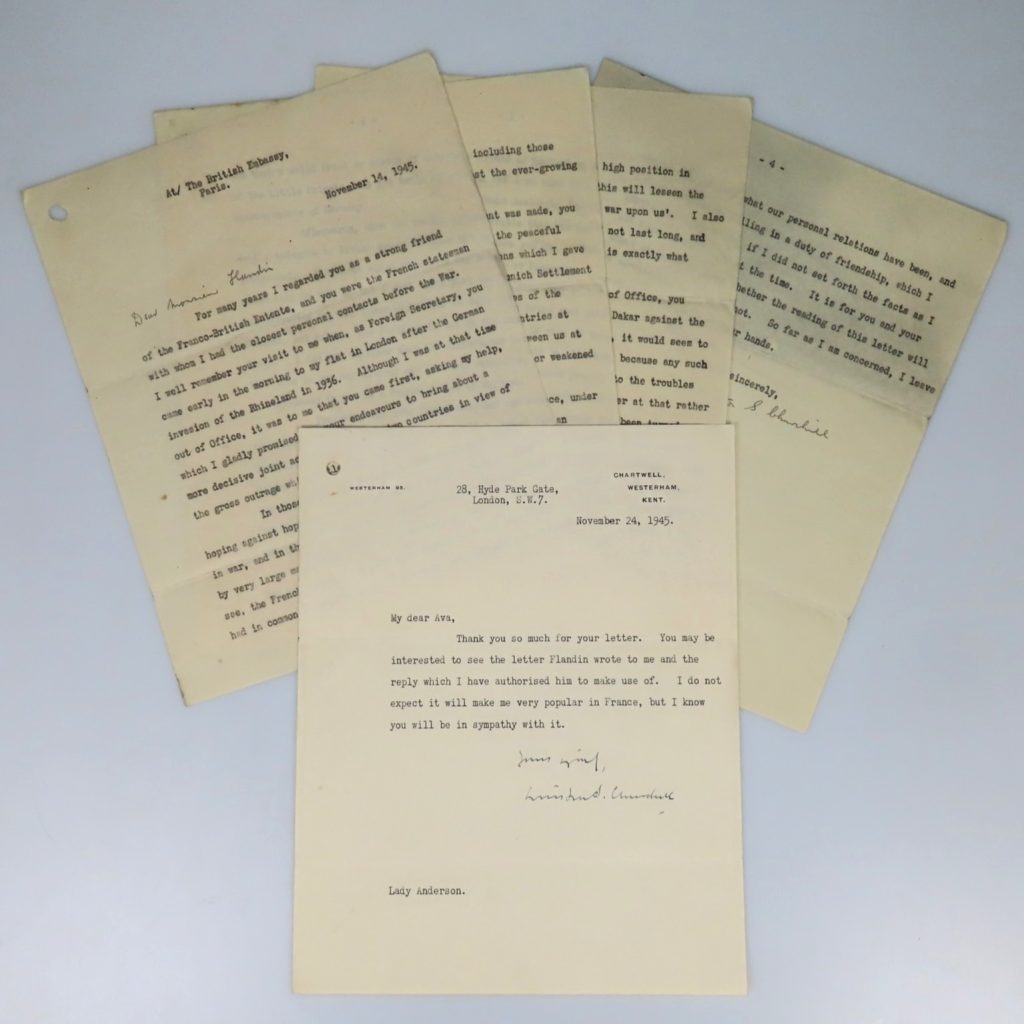

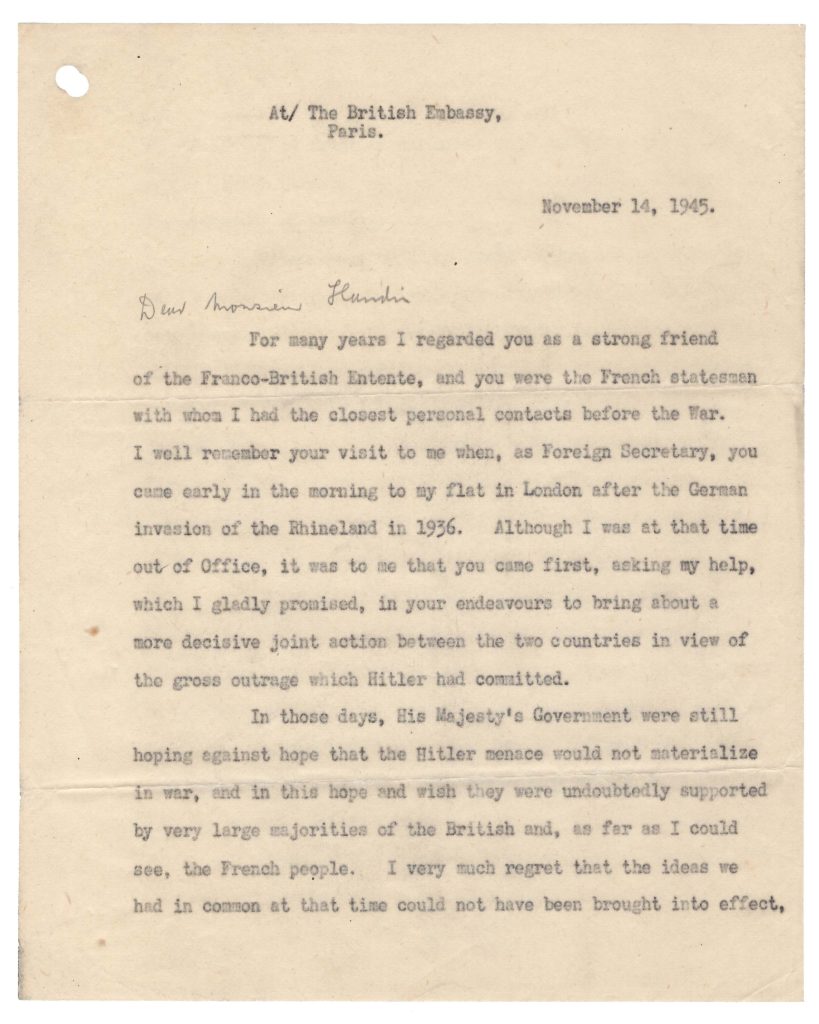

And here is where our letter comes in – the letter that introduced us to Ava and prompted this post.

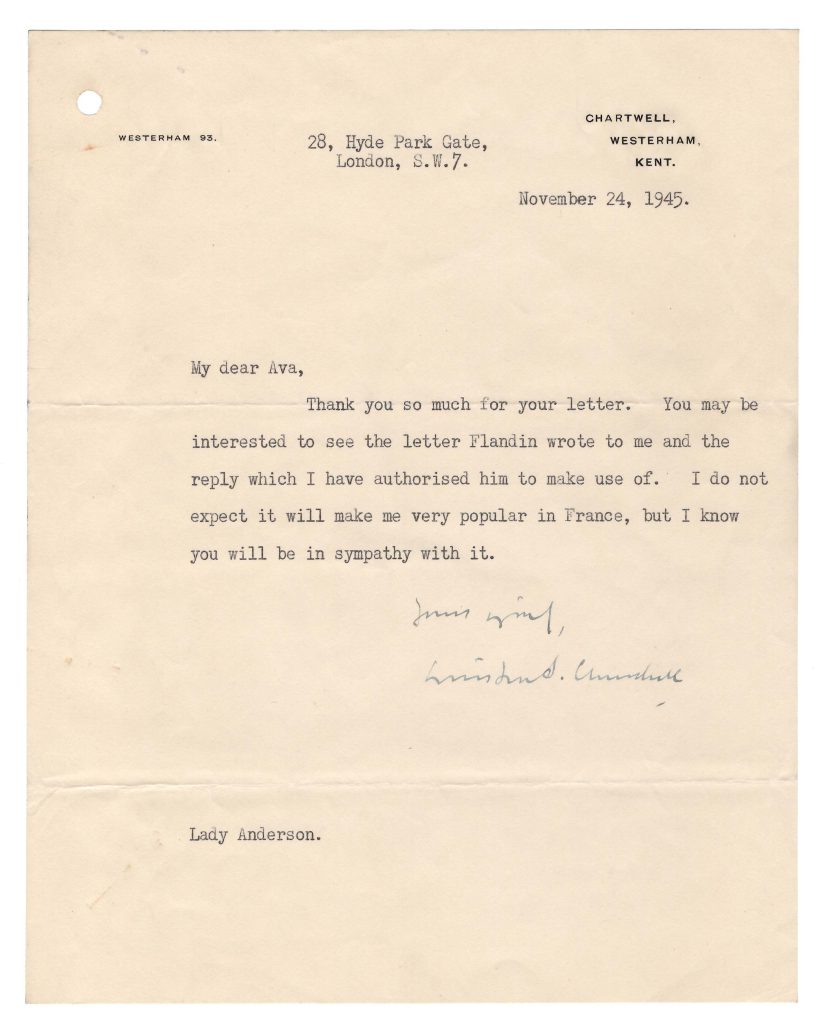

This is a 24 November 1945 typed letter signed by Winston S. Churchill to Lady Ava Anderson, his friend and stalwart 1930s anti-appeasement ally, providing her with a copy with his 14 November 1945 letter to former French Prime Minister Pierre Flandin defending him against charges of treason for his actions during the Second World War. Together, these two letters are significant testimony to Churchill’s principled loyalty, his willingness to take stands contrary to prevailing public sentiment, and his moral inclination, as he would state in his Second World War memoirs, to “In victory: magnanimity”. They are, of course, also testimony to the respect and regard Ava had earned from her friend, Winston.

The letter to Lady Anderson is typed on a single sheet of Churchill’s Chartwell stationery, with his “28, Hyde Park Gate” address typed at the head. After his warm salutation “My dear Ava,” Churchill writes “You may be interested to see the letter Flandin wrote to me and the reply which I have authorized him to make use of. I do not expect it will make me very popular in France, but I know you will be in sympathy with it.” Churchill closes with his autograph signature and valediction “Winston S. Churchill”. Appended are four sheets on thin stock comprising an apparent carbon copy of Churchill’s 14 November letter to Flandin. The copy of the letter to Flandin bears a secretarial duplication of Churchill’s autograph salutation and signature.

This item is offered for sale HERE on our website.

Flandin asked Churchill to write a letter on his behalf for submission to the court. This Churchill, did, in a letter that is an extraordinarily piece of exculpatory presentation, carefully constructed to credibly align and exonerate Flandin’s actions, without any undermining misrepresentation, hyperbole, or disrespect to the authorities with power over Flandin’s fate.

Churchill’s letter to Flandin opens by discussing Flandin’s 1936 “endeavors to bring about a more decisive joint action” between Britain and France. Aware that his own status as an early and ardent opponent to Nazi Germany was beyond dispute, Churchill refers to his and Flandin’s efforts to thwart Hitler as “we” and “in common”. More delicately handled is Flandin’s congratulation of Hitler on “the peaceful settlement” after Munich, in which, Churchill rightly points out, Flandin was “supported by very large majorities on both sides of the Channel”. Churchill handles Flandin’s short tenure as Vice-Premier and Foreign Minister in the Vichy government by saying “I was glad. I thought to myself ‘here is a friend of England in a high position…’ I also thought that the Germans would have you out. This is exactly what happened…” Churchill substantiates this interpretation: “I have heard that in your period of Office, you managed to stop an expedition being sent from Dakar against the Free French centre at Tchad…” which “would have added greatly to the troubles which General de Gaulle and I were facing together”. This was a particularly intentional alignment; over Churchill’s strenuous objections, de Gaulle had imprisoned Flandin in 1943. Churchill’s political history is replete with examples of his working with, and often befriending, those who differ with him if he believes in their integrity and intention. In closing, Churchill makes this plain: “I have always regarded you as on our side and against the common foe and his collaborators… I feel I should be failing in a duty of friendship… if I did not set forth the facts as I saw them…”

Churchillian friendship proved Flandin’s salvation. With Churchill’s permission, Flandin used Churchill’s letter in his defense and it reportedly “caused a considerable stir when read out in court.” On 23 January 1946 the charges against Flandin were dropped and he was released from custody.

That Churchill shared this letter with Ava 10 days after he wrote it testifies to the regard in which Winston held Ava, and of their shared efforts to prevent the Second World War.

Ava’s aftermath

Ava’s “Best Supporting Actress” role saw a sequel. Her second husband, new Member of Parliament John Anderson, was “an aloof, self-contained widower” who “never saw colleagues at his home and seldom invited guests to lunch at his club.” Once again, “Ava was gifted with the personal skills that her husband lacked.” She “supported his cabinet career” when he became Winston Churchill’s Chancellor of the Exchequer in the final years of the Second World War “and she continued to entertain despite the stresses of war.” To his credit, her husband “helped in turn to alleviate the heavy responsibility of caring for her son, Charley Wigram, who died in August 1951.”

After the war, Ava “was in her element in social and promotional activities as wife of the chairman of both the Port of London Authority and the Covent Garden Opera Trust during the period of post-war austerity and reconstruction.” Following her husband’s elevation to the peerage in 1952, Ava was known as Ava, Viscountess Waverly.

“Ava… was more than a personable adjunct to her able but socially awkward spouses. A background including entrepreneurial grandfathers, and erudite father, a detailed knowledge of French diplomatic affairs, and strong affinities with politicians, together with good organizing ability, enabled her to direct her hospitality toward practical ends. She created for herself a role over four decades as a highly regarded hostess in political and cultural circles.”

Despite a respectable general knowledge of history, if I’d not had occasion to research this letter, I’d not have known about Ava.

The enduring bond between Ava and Winston

The good news is that someone far more important than you or me, reader, knew and appreciated Ava. “Winston was devoted to Ava for the rest of his life, as she was to him. Ava had taken a photograph of Winston and Ralph Wigram walking on the grounds of Chartwell. Winston signed it and Ava inserted a press cutting of Winston’s June 18, 1940 ‘finest hour’ speech. This framed photograph stood at her bedside until her death in 1974.”

Cheers!

Churchill Book Collector

References: Marsh, Churchill, Flandin, and Wigram: The Rest of the Story; Gilbert, Vol. VIII; Churchill, The Second World War: The Gathering Storm; ODNB; Hillsdale College: The Churchill Project