On the morning of Monday the 26th of August, my daughter moved into her new dorm room at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Later that afternoon, we said goodbye and parents were ushered off of the campus and sent home so that their progeny could settle into their new life as college students. I spent a lot of the day looking upwards. Perhaps that’s because the late summer cloudscapes of coastal Maine are breathtaking and the trees are stately and tall. It might also be because when you look up, your eyes are less likely to leak and your daughter is less likely to notice that you are trying to prevent your eyes from leaking. Allergies, I’m sure, from all that exotic Maine pollen.

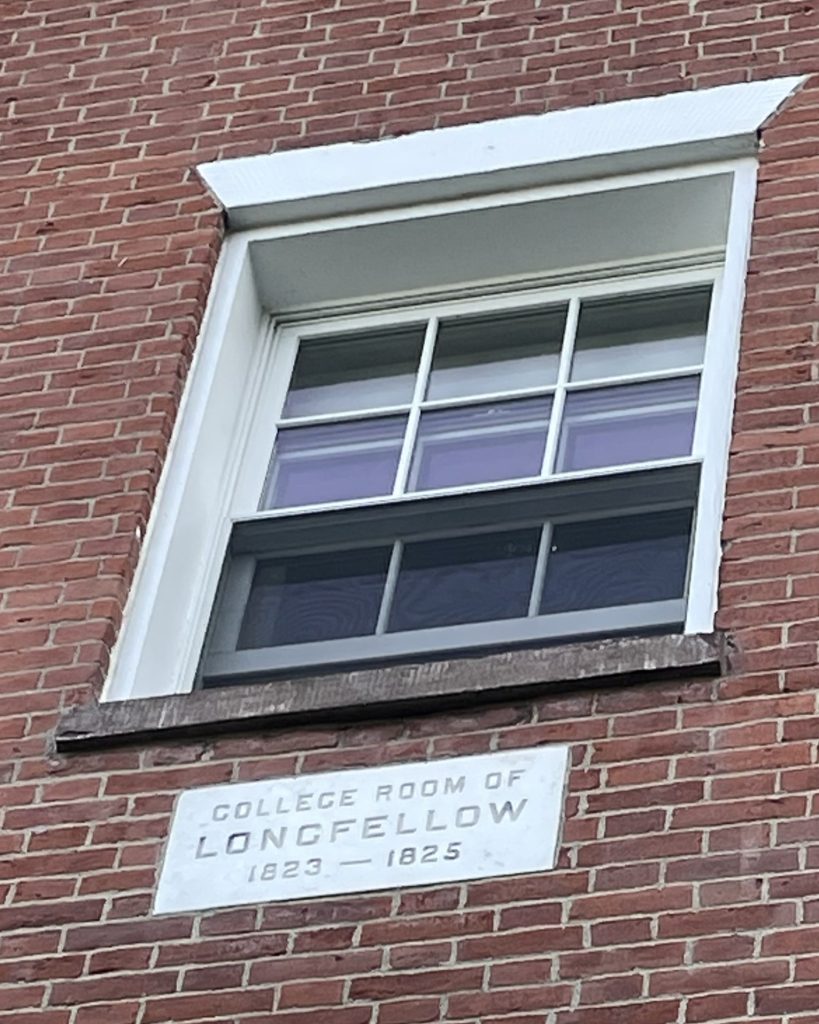

Anyway, there I was, at the Northwest corner of my daughter’s dorm building, hands on hips and looking up from her first-floor window, through which I had seen her unpacking and settling in. I could feel my eyes starting to water – you know, because of the pollen – so I looked up. There appeared to be an anomaly in the otherwise regular pattern of brick exterior interspersed with windows. A stone plaque was set into the wall below the window sill two floors directly above my daughter’s own. Once my eyes cleared (damned pollen) I could read what it said:

COLLEGE ROOM OF

LONGFELLOW

1823-1825

Assuming this was not just an extravagantly permanent homage to the physical endowments of a former student, my daughter now resides in the same corner of the same dorm occupied two hundred years ago by the great American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Looking up at Longfellow’s dorm room window, I remembered an early Second World War exchange between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston S. Churchill involving Longfellow.

When Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940, the war for Britain was not so much a struggle for victory as a struggle to survive. Churchill’s first year in office saw, among other near-calamities, the Battle of the Atlantic, the fall of France, evacuation at Dunkirk, and the Battle of Britain. Hitler intended the massive, sustained attacks by his Luftwaffe to achieve air superiority preparatory to an invasion of England. Sapping Britain’s Air Force and war-making capacity was of course a goal. But so too was the simple goal of terrorizing Britons and eroding their will to fight. As the year 1941 began, Churchill’s Britain had held on with remarkable resolve and resourcefulness, but her position remained tenuous. The United States would not formally enter the war until the end of the year, after the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

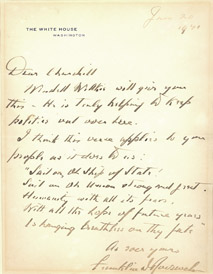

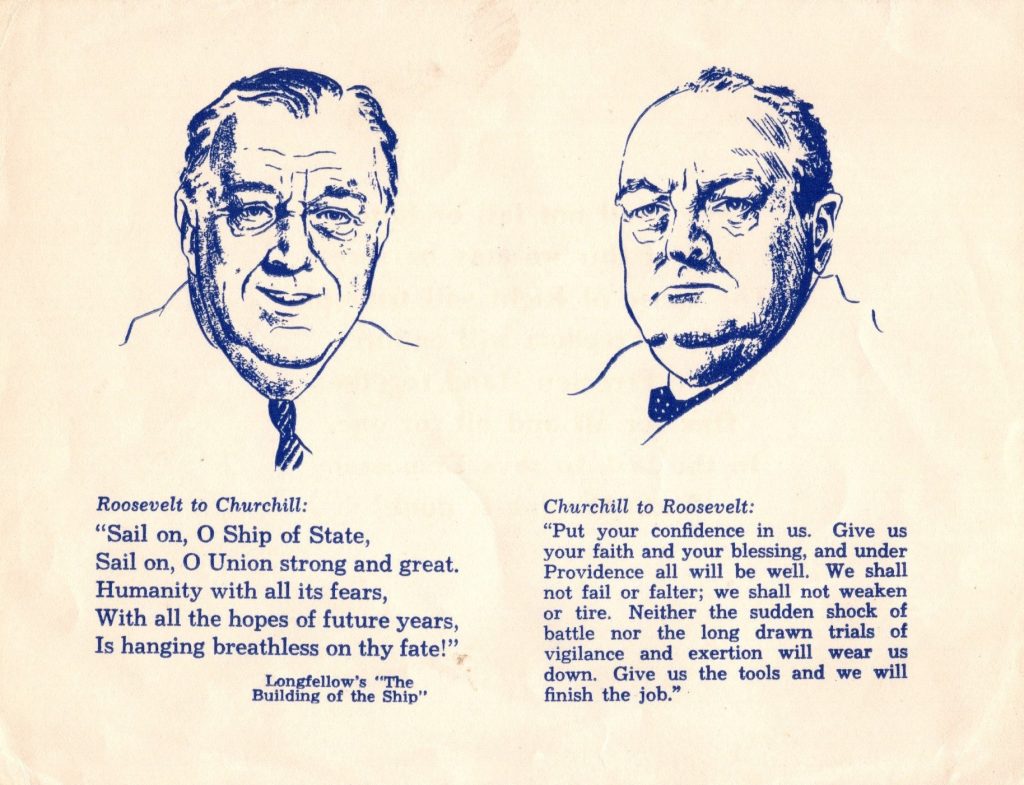

In the brutal interval, the Lend-Lease Act gave Britain both vital material aid and an equally vital expression of support. On Saturday, 8 February 1941, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Lend-Lease Bill by 260 to 165 Votes. It had yet to pass the Senate and be signed by President Roosevelt, but a major hurdle absolutely crucial to the British had been passed. Churchill’s broadcast address to Britain and the Empire the next day, 9 February, was his first broadcast for five months. He was well aware that a significant element of his audience was American public opinion. Near the end of his remarks, Churchill quoted verse from a Longfellow poem which President Roosevelt had written out in his own hand and sent to Churchill on January 27:

“Sail on, O Ship of State!

Sail on, O Union, strong and great!

Humanity with all its fears,

With all the hopes of future years,

Is hanging breathless on thy fate.”

Churchill concluded his 9 February broadcast with his answer to President Roosevelt: “Put your confidence in us. Give us your faith and your blessing, and under Providence all will be well. We shall not fail or falter; we shall not weaken or tire. Neither the sudden shock of battle nor the long-drawn trials of vigilance and exertion will wear us down. Give us the tools and we will finish the job.”

The United States enacted the Lend Lease Act in early March and soon thereafter extended its naval security zone several thousand miles into the Atlantic, effectively shielding much of the Atlantic convoy route.

The Lend-Lease Act was a clever, calculated, steely-eyed political balancing act. Roosevelt managed to provide essential aid to a stalwart future ally without yet overtly committing to war his nation, which was not yet committed to war. While Lend-Lease was a political masterstroke, it was hardly the stuff of rhapsodizing poetry. Why would Roosevelt send Churchill lines of verse – and in his own hand at that?

Perhaps because Roosevelt knew what the poet Mary Oliver later said of poetry – that a poem is not ‘wordplay’ but “something beyond language devices” with “a purpose other than itself… poems are not words… but fires for the cold, ropes to let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry.”

Perhaps poets and poetry have always been, and always will be, more praised than read. But I’m reminded of another story, one closer to our own time. When the Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney died in 2013, his funeral was widely attended by the good and great. But the tribute I found most affecting was the one given by football fans. A crowd of 80,000 in a Gaelic football stadium observed a full minute’s silence and then burst into applause in Heaney’s honor during a match between Dublin and Kerry.

Mary Oliver was a poet. It was no accident that she referred to “bread in the pockets of the hungry” rather than in the bellies of the hungry. We carry poetry with us, both culturally and personally, because what poetry can provide at need – encompassing perspective, edifying purpose, steadying reassurance and hope. These are fire, rope, and bread. These are necessities.

You may browse our current inventory of poetry HERE.

Cheers!

Churchill Book Collector