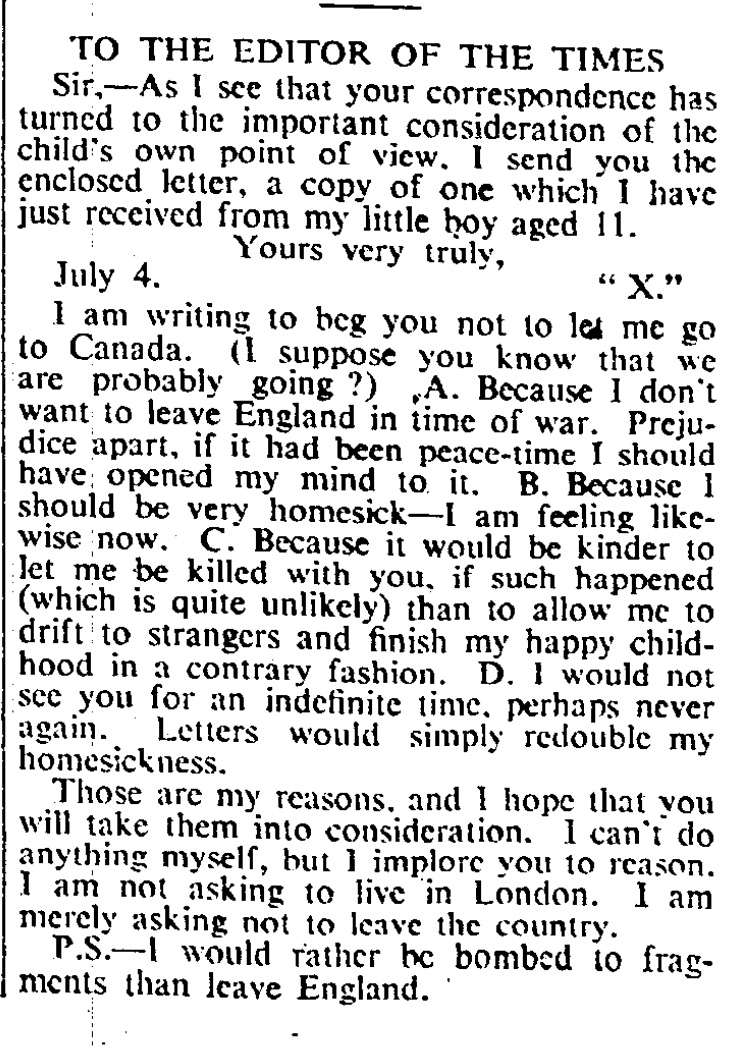

I am writing to beg you not to let me go to Canada… A. Because I don’t want

to leave England in time of war… B. Because I should be very homesick…

C. Because it would be kinder to let me be killed with you, if such happened

(which is quite unlikely)… D. I would not see you for an indefinite time,

perhaps never again… Those are my reasons, and I hope that you will

take them into consideration….

P.S. I would rather be bombed to fragments than leave England.

The 6 July 1940 edition of The Times printed this anonymous letter written by an 11-year-old boy to his father. This letter precipitated perhaps the most compelling inscribed wartime copy of Churchill’s autobiography we’ve ever encountered. This post tells the story.

When the boy’s letter was printed in The Times, the father prefaced his son’s letter thus:

“Sir, – As I see that your correspondence has turned to the important consideration of the child’s own point of view, I send you the enclosed letter, a copy of the one which I have just received from my little boy aged 11.”

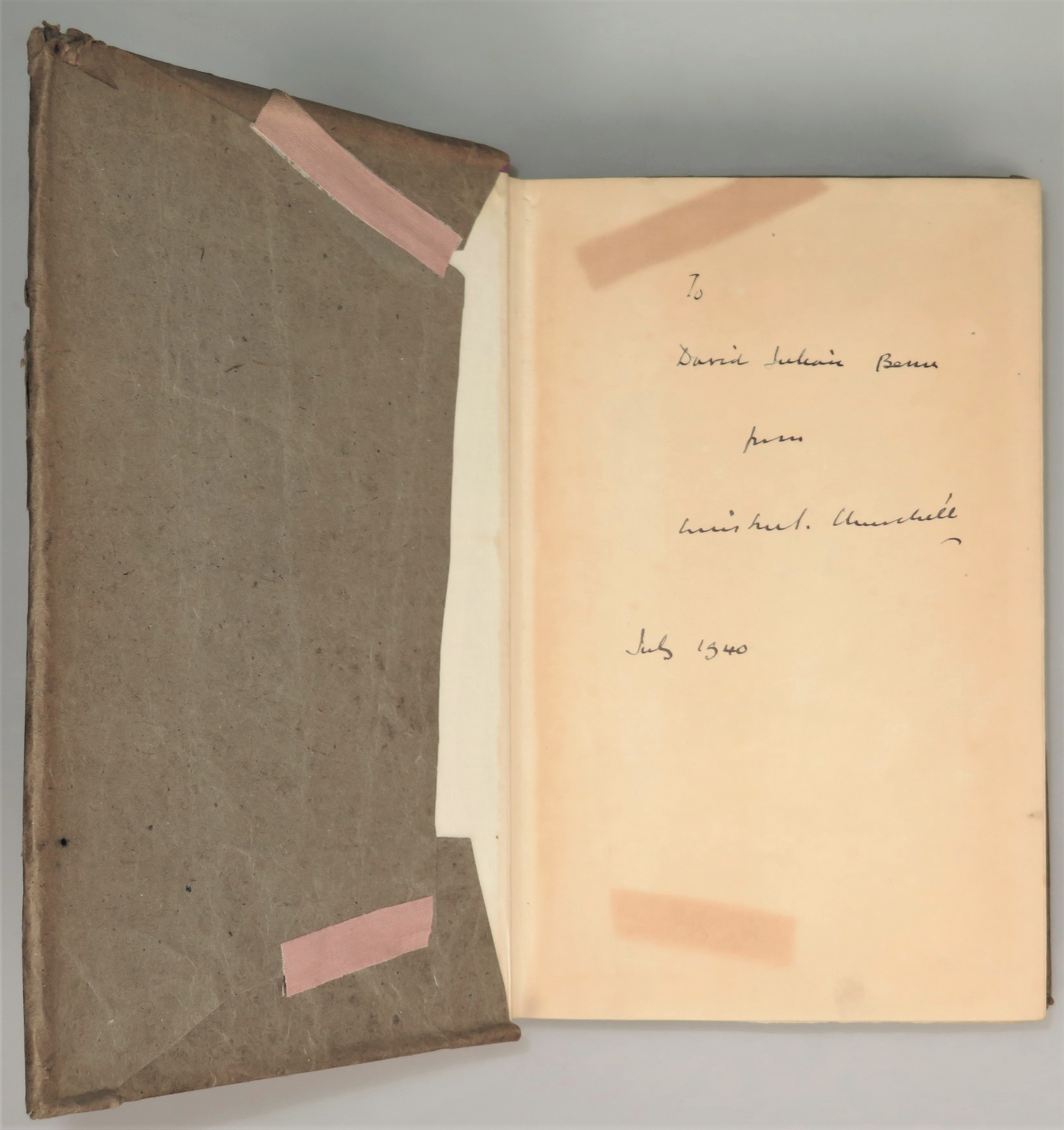

The boy’s letter caught the eye of Winston Churchill, who had been prime minister for less than two months. Churchill “instructed his office to identify the author. They did and Churchill sent the young boy an autographed volume of one of his own works in recognition of his patriotic defiance.” (Alban Webb, The Guardian, 1 March 2017)

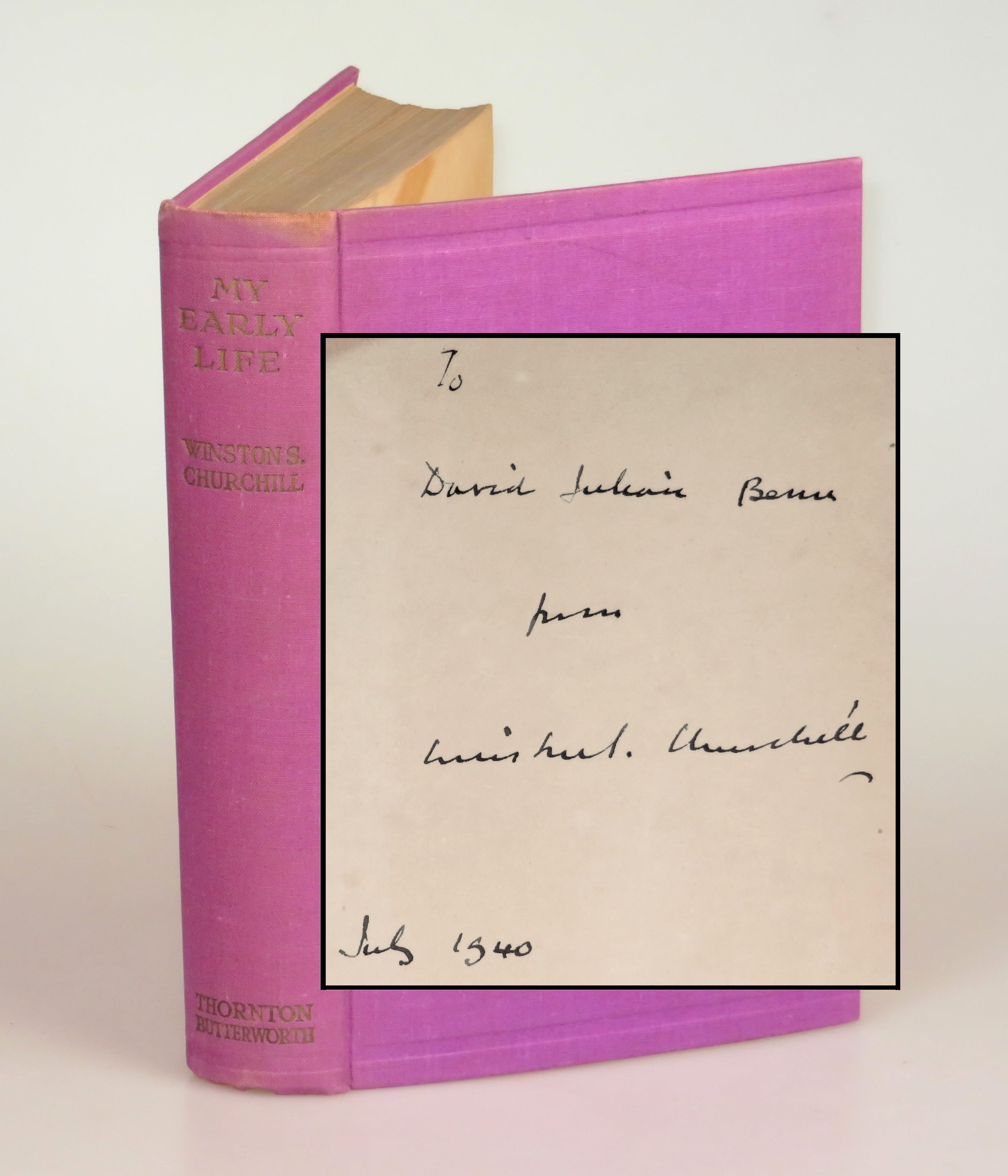

It turns out that it was not just any book, but, magnificently appropriate for a brave and precocious 11-year-old-boy, a copy of My Early Life – Churchill’s engaging story of his early years. Moreover, Churchill did not just sign and send the book, but inscribed it to the boy by name, signing and dating the volume before having it wrapped in brown paper and hand-delivered care of the boy’s father. We know because this very book, still wrapped as it was when delivered, came into our possession. We wager we were no less thrilled than the boy who first received it.

This book is a magnificently evocative artifact of the desperately imperiled days of early Second World War Britain and the fraught first months in office of her prime minister, Winston S. Churchill. The moment and family that provoked this inscribed book encapsulate both the critical struggle over the skies of Britain and the deeply-rooted sacrificial resolve that saw Britain persevere. Moreover, the brief convergence of author and recipient witnessed by this book limns an animating spirit of virtuous defiance that both shared and both employed in service to conscience and country.

THE MOMENT

When Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940, the war for Britain was not so much a struggle for victory as a struggle to survive. Churchill’s first months in office saw, among other near-calamities, the Battle of the Atlantic, the fall of France, evacuation at Dunkirk, and the Battle of Britain. Hitler intended the Battle of Britain as the preparatory effort to gain air superiority prior to a planned invasion of England, “Operation Sea Lion”.

Because the war’s outcome is now settled history, it is perhaps difficult to viscerally understand how imperiled Britain was in July 1940. As late as April 1941, the Ministry of Information and the Prime Minister were still issuing printed instructions to all British households regarding what to do in the case of invasion. Legitimate fear and anxiety in England were cresting in the summer of 1940.

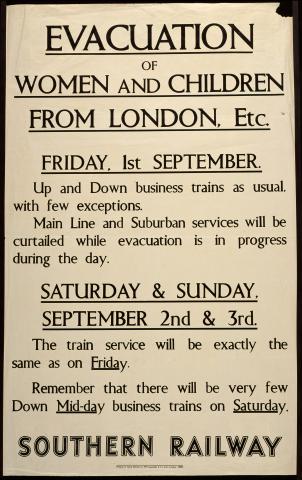

The unprecedented development of aerial military power meant that the English Channel and British Navy no longer guaranteed the safety of British homes and, in particular, of British children. “When war broke out in September 1939, fear that German bombing would cause civilian deaths prompted the government to evacuate children, mothers with infants and the infirm from British towns and cities… Over the course of three days 1.5 million evacuees were sent to rural locations considered to be safe.” Many had returned by the end of 1939 when the widely expected bombing raids on cities failed to materialize, but “additional rounds of official evacuation occurred nationwide in the summer and autumn of 1940, following the German invasion of France in May-June…” (Imperial War Museum) Some children were even evacuated overseas to other British Dominions, such as Canada. Early July, when this letter was written, was a particularly anxious moment. Germany was about to begin its aerial bombing campaign of British cities that would become known to history as “The Blitz”. Germany’s sustained aerial assault would result in many tens of thousands of British civilian casualties.

It’s worth recounting – and will become more relevant still as the story unfolds – that even before the First World War, Churchill was deeply intrigued by the possibilities of air power and fully engaged in efforts to explore the military potential. In 1913, he learned to fly and, as First Lord of the Admiralty, founded the Royal Naval Air Service and argued “for the proper funding of the Royal Flying Corps and its successor the Royal Air Force.” (Roberts, Walking with Destiny, p.128) Churchill used his post-WWI positions as Secretary of State for War and Air – in the face of considerable resistance – to make military aviation a priority. He sought to build resources and organizational capacity, but also to ensure that the Air Force remained integrated within a unified defence Ministry. Even so, he could not have known how absolutely critical a role air power would play in the survival of Britain under his own premiership decades later. This imminent aerial crucible was the catalyzing event behind Churchill’s gift of this book to young David Julian Benn.

THE BOY

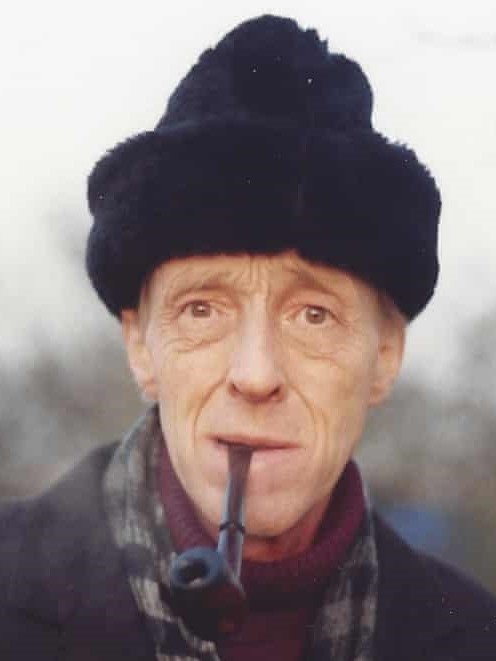

David Julian Wedgwood Benn’s (1928-2017) letter to his father proved “an early indication of David’s lifelong instinct to question received wisdoms and assumed orthodoxies, allied to a healthy sense of dissent.” These are, of course, qualities the young David would very much have recognized in the pages and protagonist of My Early Life.

David “became a linguist and scholar whose work as a barrister, BBC broadcaster, journalist and academic author reflected his determination to seek out objective truth. Dedicated to the study of international affairs, he retained an infectious and boyish curiosity for making sense of the world around him.” The Churchillian echoes hardly need underscoring.

David proved “conservative in everything but politics” but, despite socialist inclinations, he was unwilling to sacrifice conscience and justice to ideology. In fact “It was another letter, this time to the Soviet newspaper Pravda in Moscow, that led David to his long and influential career at the BBC. Shaken by the Soviet Union’s brutal repression of the Hungarian uprising, in December 1956 David organized and drafted an open letter…” signed by Labour Party leaders “requesting a justification of Soviet actions.” When the BBC Russian Service broadcast the letter, Pravda printed a reply. David ended up working for the BBC until 1984 in a career spent substantially engaged in Cold War analysis and reporting. In retirement he continued to write and publish on Cold War politics and propaganda. (Alban Webb, The Guardian, 1 March 2017) The very same “Iron Curtain” Churchill coined in 1946 would become the defining intellectual, moral, and political line in David’s career.

THE FATHER

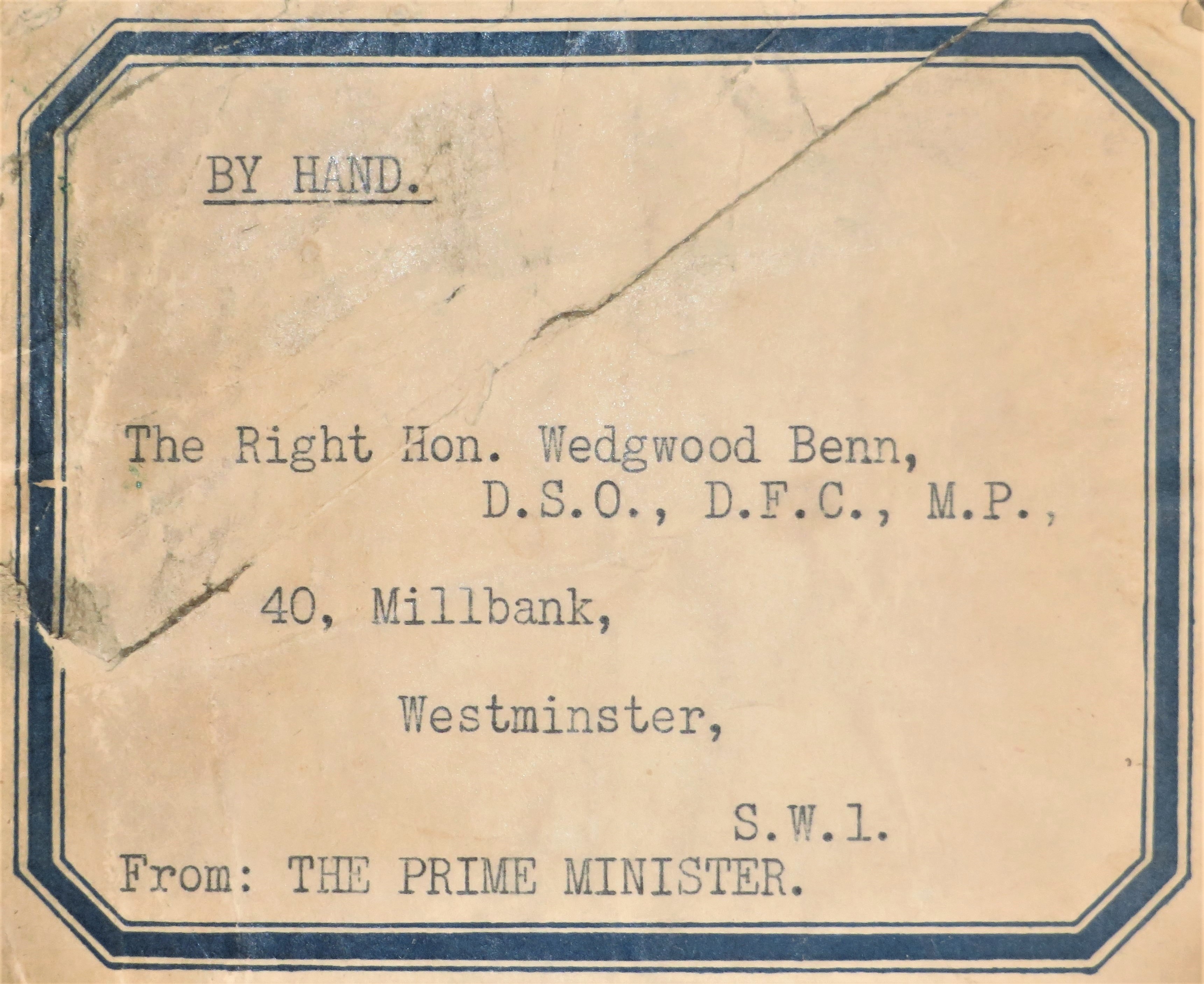

Britain’s Prime Minister was far from the only model of resolution in David’s life. Winston Churchill may have been unsurprised to discover that the father of the courageous anonymous boy whose words had captured his attention was William Wedgwood Benn (1877-1960) – the “Rt. Hon. Wedgwood Benn D.S.O., D.F.C., M.P.” to whom this book was hand-delivered after it was inscribed for David.

A month after inscribing this book, in August 1940 Churchill famously praised “British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the war by their prowess and by their devotion.” Churchill reckoned “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” He could rightly have had Wedgwood Benn in mind.

Benn, a decorated First World War veteran, was first a Liberal and then a Labour MP who served as Secretary of State for India (1929-31) and, as 1st Viscount Stansgate, Secretary of State for Air (1945-46). Of course, the first man to hold the post of Secretary of State for Air had been Winston Churchill in 1919. During the First World War William served in Churchill’s Royal Naval Air Service, qualified as a pilot, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Distinguished Flying Cross, among other honors. But decades after he earned the D.F.C. and well before he ascended to the ministerial position, in May 1940 William joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve – despite being in his 60s.

Though officially grounded, William “was known to have taken part in air operations” and may even have been the oldest man to serve as an RAF Bomber aircrew gunner. He resigned his commission in August 1945 with the rank of air commodore. David’s two older brothers, Michael and Tony, also both served in the RAF. Michael was killed in a crash in 1944. (ODNB) Tony entered the House of Commons as its youngest member in 1950, remaining until 2001 and becoming the Labour Party’s longest-serving MP.

THE BOOK

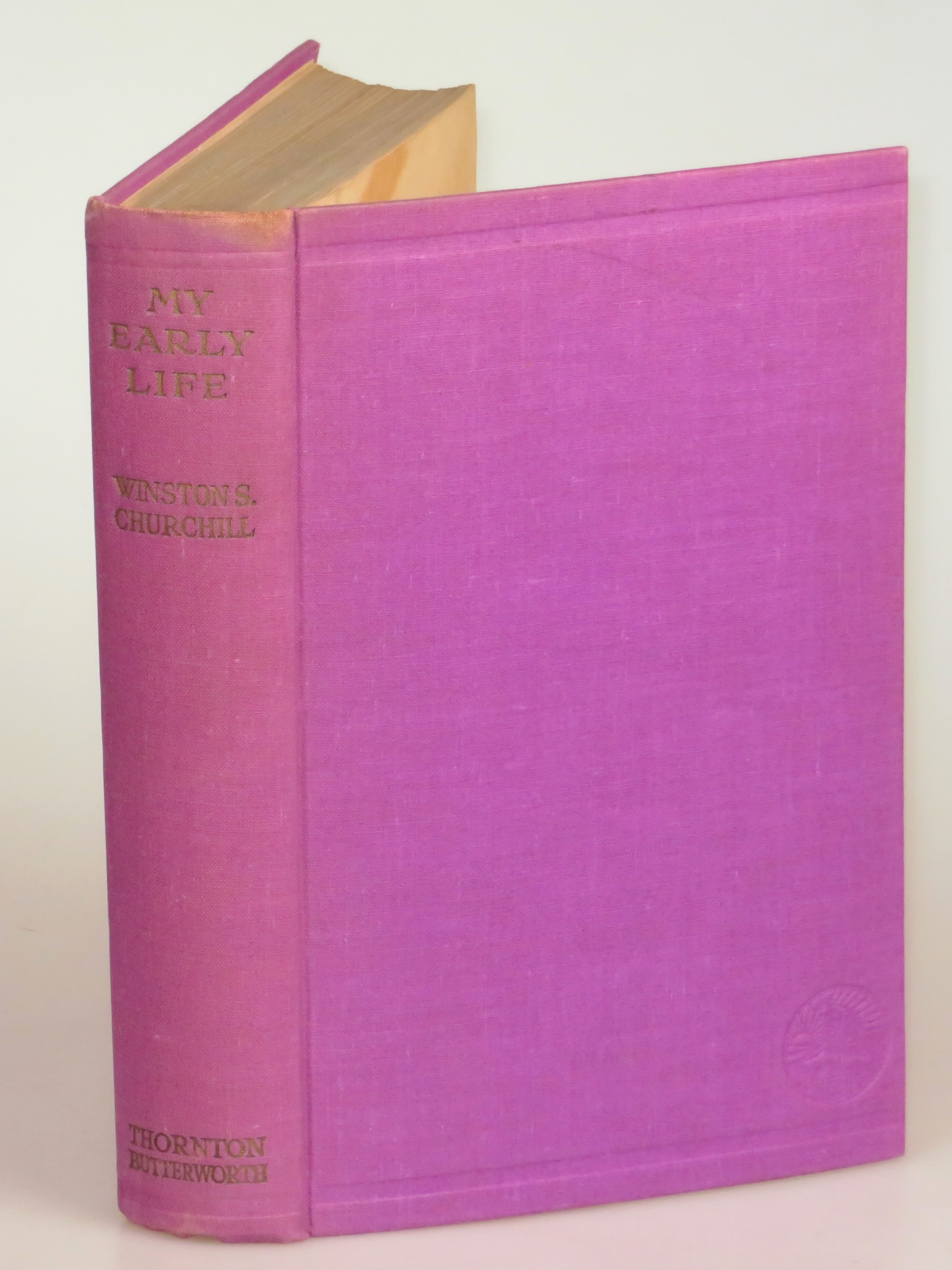

The book itself, though wonderfully well-preserved, is the bibliographically humble third printing of the Keystone Library issue. The first edition was published by Thornton Butterworth Limited in 1930, when the recipient of this inscribed copy was still in diapers. The Keystone Library issue was published by Thornton Butterworth in the same setting and binding style as the first edition beginning in 1934. This third printing of the Keystone Library issue was published in January 1940, and thus would have been the most current British publication of My Early Life readily available at the time Churchill inscribed it as a gift to young David.

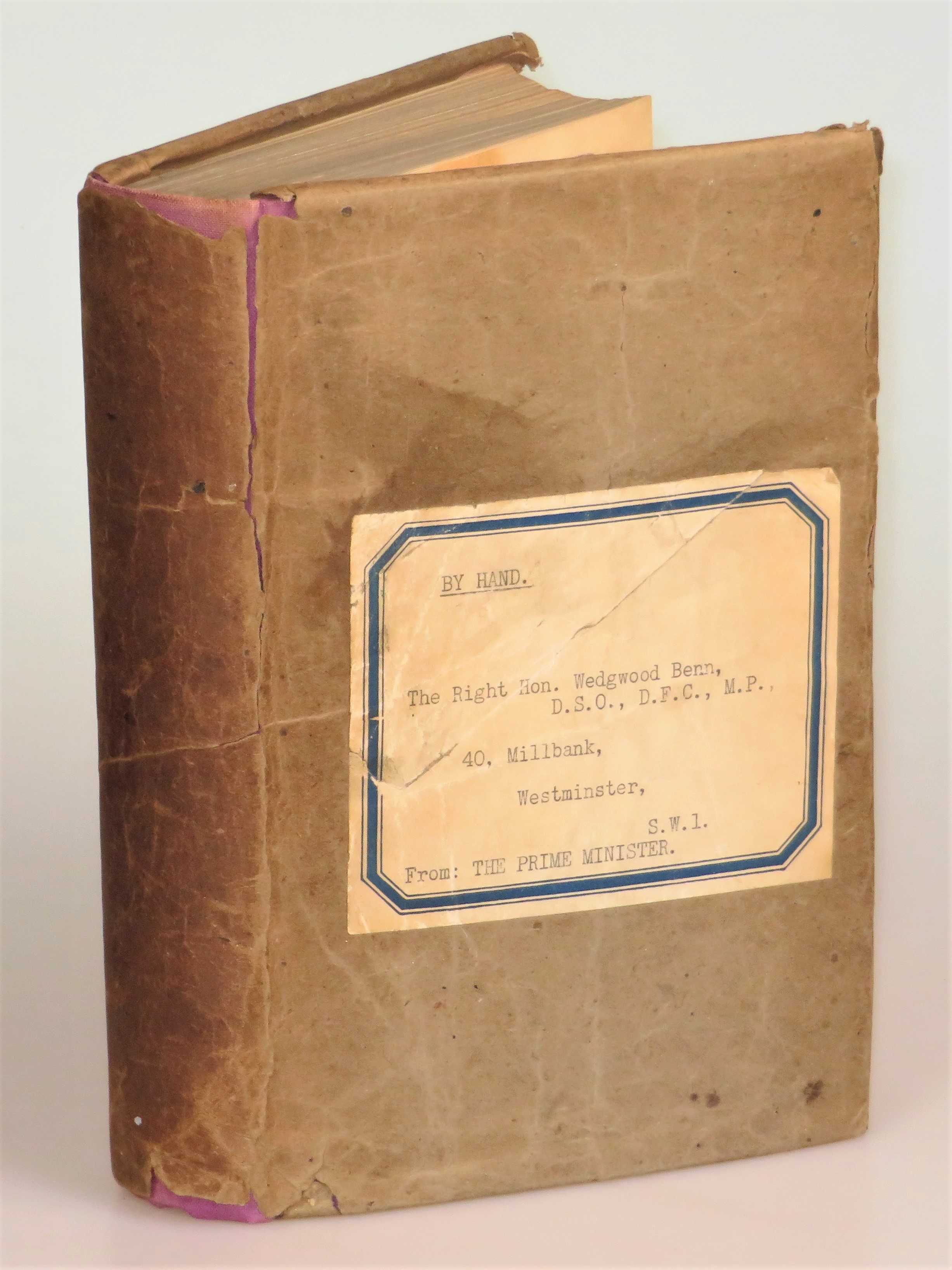

Though it was originally issued in a dust jacket, this copy obviously had its dust jacket removed when it was inscribed. Its current wrapping is testament to the English mania for wrapping things in brown paper. At the time it was gifted via hand delivery to David’s father, the book was carefully wrapped in brown paper carefully folded over the covers by means of flaps that were secured with tape. Clearly the brown paper and tape are original. The tape has left stains where it lay against the end sheets over the long years. Of far greater interest, Churchill’s office affixed to the brown paper cover a typed, blue-bordered label that reads, in seven lines:

“BY HAND.

The Right. Hon. Wedgwood Benn,

D.S.O., D.F.C., M.P.,

40, Millbank,

Westminster,

S.W.1.

From: THE PRIME MINISTER.”

We may reasonably assume that the dust jacket was removed by the Prime Minister’s office, replaced by the brown paper cover and delivery label. The original brown paper cover and the Prime Minister’s delivery label remain. The brown paper shows some wear to extremities and is split along the front hinge. The label is a bit soiled and worn, but nonetheless intact and clearly legible. Condition of the book beneath implies that it was both purchased new for the purpose of inscription and presentation and treasured thereafter as a gift. The vivid purple cloth binding remains beautifully bright and clean. The contents are equally untouched, showing only transfer browning to the endpapers and some age-toning, mostly evident to the page edges.

Precious few inscribed copies survive in such well-preserved condition. Indeed, arguably few were signed at this time so early during Churchill’s premiership; he was rather fully engaged in the pressing events of the day. Moreover, many inscribed early wartime copies of Churchill’s books either have long since entered the marketplace or remain held by families and institutions. In this case, explaining the appearance of this book eighty odd years after it was inscribed we have the unusual facts that David Wedgwood Benn was gifted this book at such a young age and lived such a long life thereafter.

Doubtless the specific choice of My Early Life for 11-year-old David Wedgwood Benn was intentional. In early wartime Britain under Churchill’s premiership, it is difficult to imagine a more fitting literary gift to a precociously verbal young man than Churchill’s own story about his early life. My Early Life covers the years spanning Churchill’s birth in 1874 to his first few years in Parliament, including his time as an itinerant war correspondent and cavalry officer, his early years as an author, and his capture and daring escape during the Boer War. Churchill took some liberties with facts and perhaps deceptively lightened or over-simplified certain events, but this is forgivably in keeping with the wit, pace, and engaging style that characterize the book. Certainly, Churchill’s style and liberties would have done nothing to diminish the book’s appeal to a determined young man surrounded by the conspicuous, unstinting, and intrepid courage of his father and older brothers.

“Come on now all you young men… You are needed more than ever now to fill the gap of a generation shorn by the War… Enter upon your inheritance, accept your responsibilities… Don’t take No for an answer… You will make all kinds of mistakes; but as long as you are generous and true, and also fierce, you cannot hurt the world or even seriously distress her. She was made to be wooed and won by youth.”

(Churchill, My Early Life, p.74)

EPILOGUE

It does not seem that either David or his father was of a temperament to abide sending David away from Britain during her darkest hours. Even had they been so inclined, the notional avenue was soon closed, not by David’s father, but by events. “In September 1940, the SS City of Benares travelling from Liverpool to Canada was sunk with the loss of 77 children… The British government immediately stopped the overseas evacuation scheme.” (The National Archives)

2 thoughts on ““From: THE PRIME MINISTER” – the story of an extraordinary inscribed wartime copy of Churchill’s My Early Life”