In 1955, a dozen years before the film starring Sidney Poitier, Katharine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracy, octogenarian Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill starred opposite a young Queen Elizabeth II, more than half a century his junior, in their own version of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Substitute generational separation for racial segregation and the vicissitudes of time for the vulgarities of prejudice and we have the scene…

Churchill was 80 years old when he resigned as Prime Minister on 5 April 1955. By that time, Churchill’s Parliamentary career spanned more than half a century. During every decade of that half century Churchill had held Cabinet office, including high Cabinet office during both world wars and two premierships spanning more than eight and a half years at 10 Downing Street. By contrast, Queen Elizabeth II was just 28 years old and had been monarch for little more than three 3 of the 69 years she has reigned to date.

On the evening of 4 April 1955, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip paid Churchill the unprecedented honor of dining with him at 10 Downing Street on his final night as Prime Minister. “Among the guests were not only Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison, and their wives, but also Anne Chamberlain, Neville Chamberlain’s widow. Churchill’s after-dinner speech that evening was his last as Prime Minister. The notes from which he spoke have survived, set out, as were so many of his speeches, in the ‘speech form’ or ‘psalm form’, as his secretary called it, which he had used for more than half a century:”

Raising his glass, Churchill led his guests in toasting “The Queen.” After the toast, guests departed and the Queen was escorted to her car by Churchill. (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, p.1120)

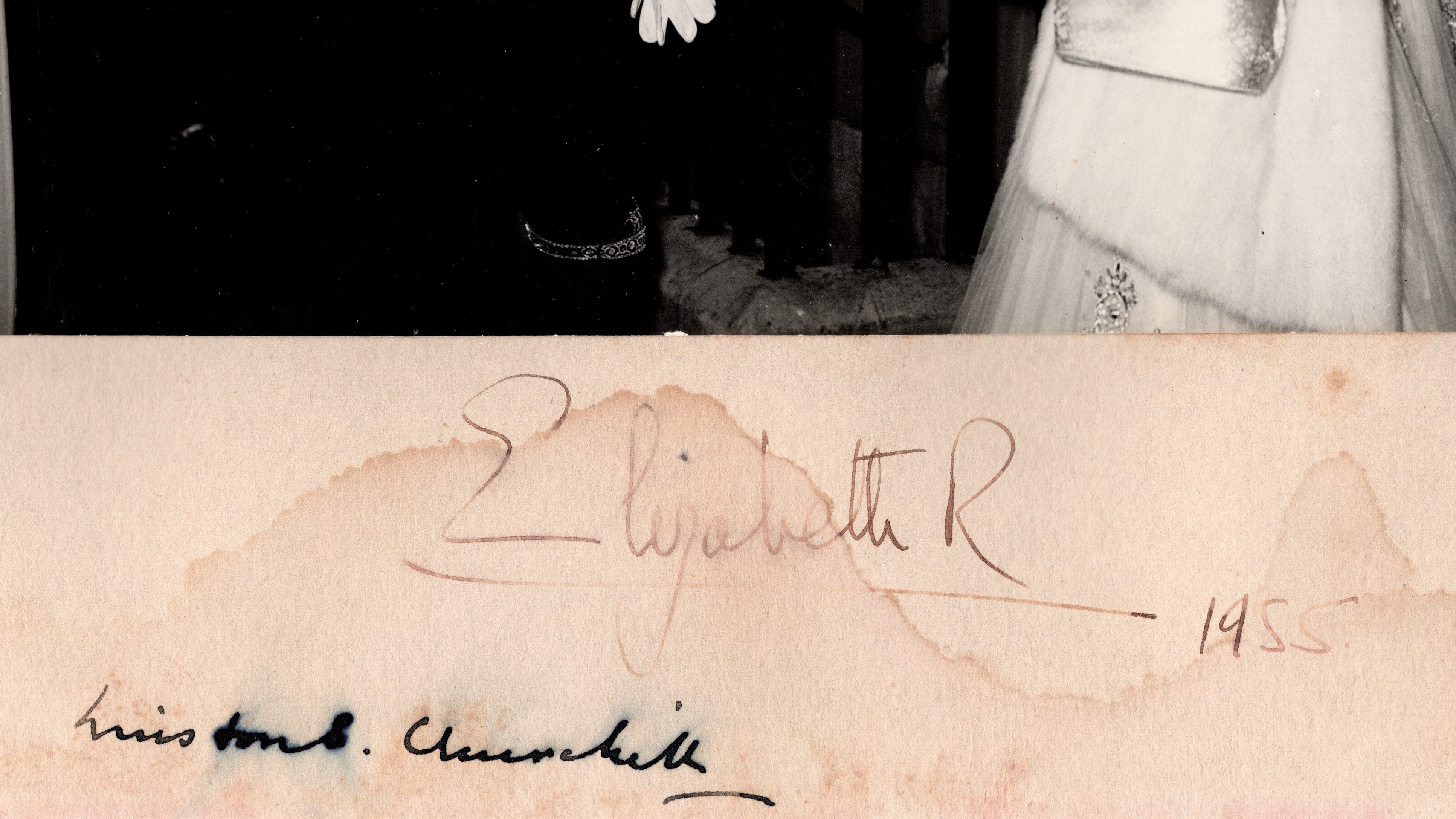

We were recently reminded of the moment by a rather extraordinary item – a photograph of Churchill escorting the Queen to her car, signed by both the Queen and Churchill in 1955. The photograph is mounted on heavy cream card, signed below the image by both subjects. Centered directly below the image, Queen Elizabeth II signed “Elizabeth R”. Slightly below and to the right, she dated her signature “1955”. Churchill signed “Winston S. Churchill” below and to the left.

Regrettably, it appears that some time ago the signed, bottom portion of the mount was briefly exposed to moisture. We’d be willing to see flogging re-integrated into the justice system just to appropriately punish those who caused or allowed this damage. But despite the aesthetic detraction to an otherwise compelling piece of history, these are unequivocally and still quite legibly the signatures of Britain’s longest reigning monarch and the first and most iconic prime minister of her unprecedented reign. And the moment captured – both in their image and their signatures – is unequivocally poignant, a lovely intersection of two of the great figures of twentieth century Britain, each honoring one another, one entering the twilight of his long service, the other newly embarked upon hers.

After the Queen left 10 Downing Street that night, Jock Colville, Churchill’s Private Secretary, recorded that Churchill “sat on his bed, still wearing his Garter, Order of Merit and knee-breeches. For several minutes he did not speak… Then suddenly he… said with vehemence: “I don’t believe that Anthony [Eden] can do it.”” (Colville, The Fringes of Power, pages 707-9) He was right. But perhaps he was also voicing the sentiment of his secretary, Elizabeth Gilliatt: “I had wished he could die in office.” (Gilbert, Vol, VIII, p.1125)

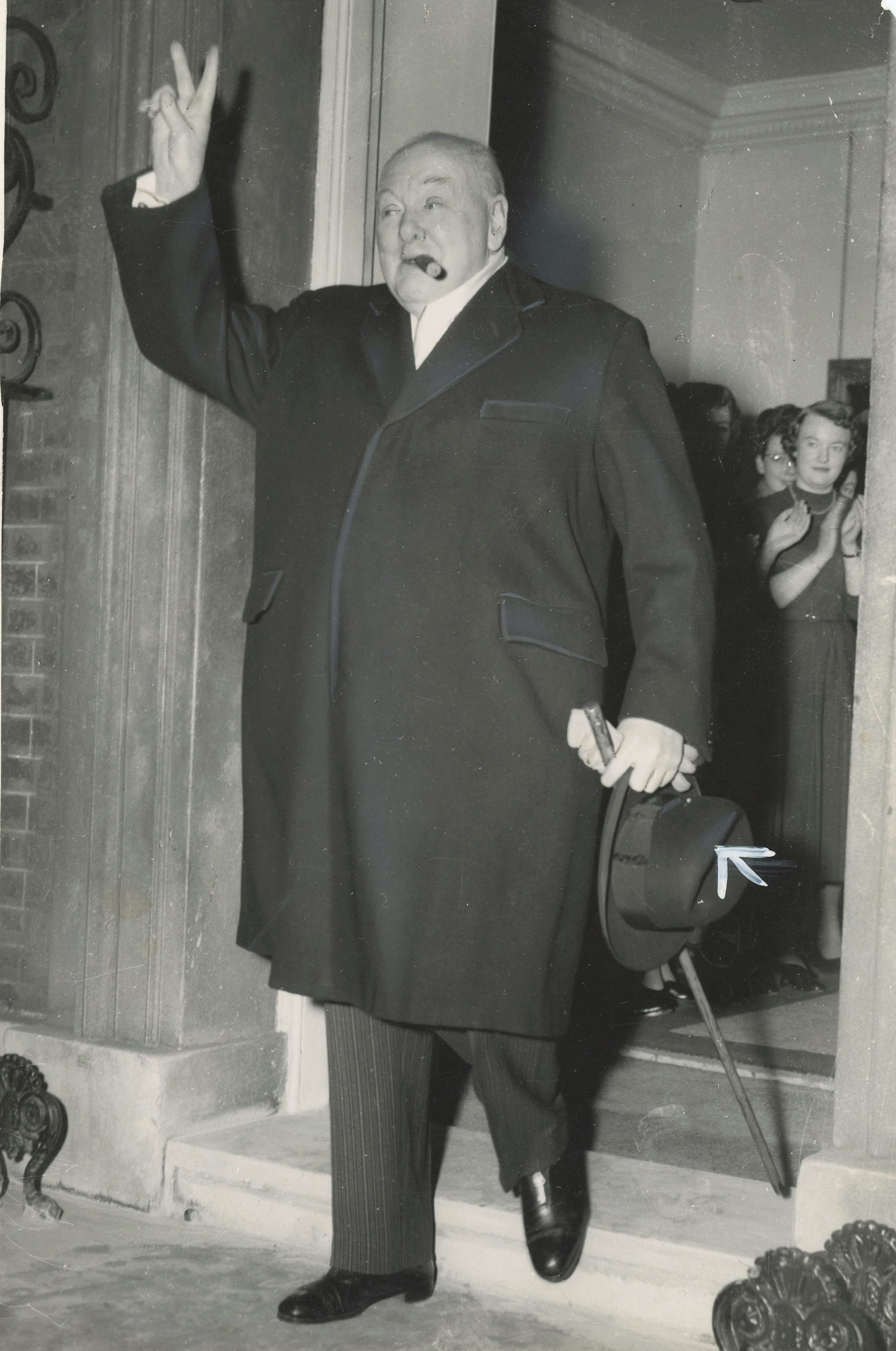

At noon the next day, Churchill held his last Cabinet “almost fifteen years after the first Cabinet of his wartime administration, and almost fifty years since he had first sat in Cabinet.” (Gilbert, VIII, p.1122) Then Churchill strode out the front door of 10 Downing Street – the moment captured by this image, in which staff can be seen applauding – to go to Buckingham Palace for his last Audience with the Queen as Prime Minister and formally submit his resignation.

A final bit of theater lay ahead. When Churchill resigned, the Queen offered him a dukedom (having earlier ascertained from Colville that he would refuse the offer – in keeping with the notion that no further dukedoms would be given to non-Royal personages). Fortunately for all, the greater temptation of ending his life in the House of Commons caused Churchill to decline. Churchill later told Colville, “I very nearly accepted, I was so moved by her beauty and her charm and the kindness with which she made this offer… But finally I remembered that I must die as I have always been – Winston Churchill.” Unaware that Colville himself had reassured the Crown that the offer would be refused, Churchill noted “…it’s an odd thing, but she seemed almost relieved.”

The ceremonial offer of the dukedom aside, the Queen’s regard for Churchill was clearly genuine. The Queen wrote that same day to Churchill’s wife: “Though I don’t think it was intentional that your kind invitation to dinner should be a farewell occasion, in fact it could not have been more perfectly arranged, coming just before today’s resignation. I hope you will both now have time for rest and relaxation in the sun…” Churchill became “a living national memorial” of the time he had lived and the Nation, Empire, and free world he had served.

Less than 10 years later, the Queen redoubled the farewell dinner honour she had bestowed on Churchill. The day after Churchill died, on 25 January, 1965, the Queen sent a message to Parliament announcing: “Confident in the support of Parliament for the due acknowledgement of our debt of gratitude and in thanksgiving for the life and example of a national hero” and concluded “I have directed that Sir Winston’s body shall lie in State in Westminster Hall and that thereafter the funeral service shall be held in the Cathedral Church of St. Paul.” This was in accord with longstanding plans; twelve years before, in 1953, at Queen Elizabeth II’s direction, planning for Churchill’s eventual state funeral had begun. The elaborate plans, running to hundreds of pages, came to be called “Operation Hopenot”.

Churchill’s state funeral was attended by the Queen herself, other members of the royal family, the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, and representatives of 112 countries. It was the first time in a century that a British monarch attended a commoner’s funeral.

The outpouring of national and international regard – from friends and foes, sympathizers and opponents alike – was both remarkable and effusive. Before the service in St. Paul’s Cathedral, Churchill’s coffin had passed through the countryside on a train. The Oxford don, Dr. A. L. Rowse, recorded “The Western sky filled with the lurid glow of winter sunset; the sun setting on the British Empire.” Arguably that glow was already apparent in this image of Britain’s young Queen and her first Prime Minister.