The broad sweep of history is something Winston Churchill comprehended and communicated with extraordinary facility. The proverbial “big picture”. Naturally, we value the commanding views of the few great figures who conspicuously shape events. But the voices of the many who are quietly living history are often lost. When we are able to hear them, such voices can impart a more intimate and richly textured human scale.

Which brings me to the subject of this post.

With genuine excitement, we have just catalogued a unique, handmade book in which the writer, photographer, and compiler, Dalton Newfield (1918-1982) chronicled – in words and photos – the impromptu, unsanctioned, and rather remarkable European tour by jeep in the days immediately following the surrender of Japan in August 1945.

With genuine excitement, we have just catalogued a unique, handmade book in which the writer, photographer, and compiler, Dalton Newfield (1918-1982) chronicled – in words and photos – the impromptu, unsanctioned, and rather remarkable European tour by jeep in the days immediately following the surrender of Japan in August 1945.

It so happens that Dalton Newfield was later the world’s first Churchill-specialist bookseller. He also became the senior editor of the International Churchill Society’s journal, Finest Hour. But while this earns him our enduring respect and appreciation, it has little to do with why we are writing about Dalton today.

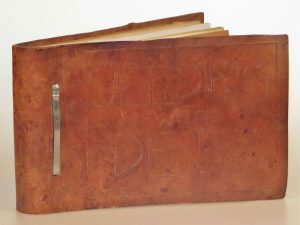

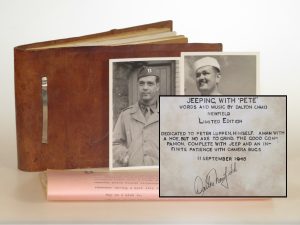

Dalton’s unpublished, previously unknown, and strikingly interesting little book, Jeeping with ‘Pete’ is 67 pages of often dense typed narrative illustrated with 87 original photos and 13 European postcards of the era. It is bound in thick brown leather, which Dalton meticulously incised with the title on the front cover and bound with a metal strip.

Dalton’s unpublished, previously unknown, and strikingly interesting little book, Jeeping with ‘Pete’ is 67 pages of often dense typed narrative illustrated with 87 original photos and 13 European postcards of the era. It is bound in thick brown leather, which Dalton meticulously incised with the title on the front cover and bound with a metal strip.

During the Second World War, Dalton Newfield served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. After the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, Dalton decided to see Europe for himself in the war’s immediate aftermath. Newfield took with him a lighter he engraved for every country he visited and the title’s eponymous “Pete” – his friend Peter Luppen. His book records what he saw and how he saw it during an epic and improbable road trip.

During the Second World War, Dalton Newfield served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. After the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, Dalton decided to see Europe for himself in the war’s immediate aftermath. Newfield took with him a lighter he engraved for every country he visited and the title’s eponymous “Pete” – his friend Peter Luppen. His book records what he saw and how he saw it during an epic and improbable road trip.

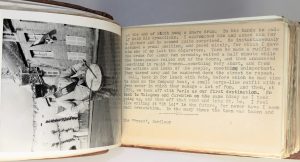

Dalton’s prose is neither polished nor deliberatively philosophical, evidently typed as he went along and peppered with spelling, typing, and grammatical errors. But there is pith and thoughtful observation evident in both his words and his photographs. Dalton’s photography is better than amateur and can be truly moving.

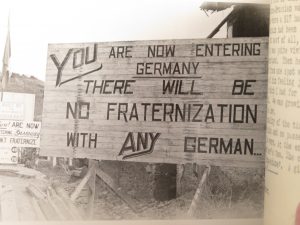

His images capture a diverse range of subjects. Nuns in Paris. Turbaned Moroccan soldiers posing with lederhosen-clad children in Austria. Men excavating the rubble of a bombed town. Allied edicts posted along the German border. Abandoned vehicles on the Autobahn. Boats laying quietly out of the water in a fishing port. A disheveled little girl, small and barefoot in the bright sun with a shadowed stone wall and a darkened, bomb-damaged church in the background.

His images capture a diverse range of subjects. Nuns in Paris. Turbaned Moroccan soldiers posing with lederhosen-clad children in Austria. Men excavating the rubble of a bombed town. Allied edicts posted along the German border. Abandoned vehicles on the Autobahn. Boats laying quietly out of the water in a fishing port. A disheveled little girl, small and barefoot in the bright sun with a shadowed stone wall and a darkened, bomb-damaged church in the background.

This was neither an official nor a sanctioned adventure. As Dalton observed: “Our orders are a bit questionable, as mine only carry me to Paris definitely and Petes don’t carry him to any particular place.” Dalton explains “…we talked over our choice between going like hell and seeing a little bit of a lot of different places, and taking it easy and seeing a lot of a few… we chose the former…” Dalton and Pete made a remarkable dash of a trek, crossing through France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.

This was neither an official nor a sanctioned adventure. As Dalton observed: “Our orders are a bit questionable, as mine only carry me to Paris definitely and Petes don’t carry him to any particular place.” Dalton explains “…we talked over our choice between going like hell and seeing a little bit of a lot of different places, and taking it easy and seeing a lot of a few… we chose the former…” Dalton and Pete made a remarkable dash of a trek, crossing through France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.

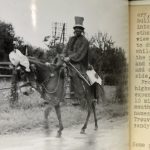

Starting off in Cherbourg, France on 19 August 1945, the duo began their journey south to Paris. Along the way Dalton gives an affecting depiction of the ways in which life in small towns in France simultaneously showed the scars of the War’s technological assault and retained their nearly pre-industrial ways of life. Phot ographs depict a liberation parade with revelers riding donkeys and floats pulled by horses. A pair of fisherman bait their lines and coil them into baskets. A town crier beats a drum to summon townsfolk, before delivering news.

ographs depict a liberation parade with revelers riding donkeys and floats pulled by horses. A pair of fisherman bait their lines and coil them into baskets. A town crier beats a drum to summon townsfolk, before delivering news.

“…at the very end of the main street we found the town crier. He was very shabbily dressed in remnants of what may have been great glory in the past. Perhaps in peacetime he will recoup. He had on a faded blue shirt and old, dirty, black trousers. On his head a jaunty, if dusty, pillbox hat. Across his chest a leather strap… at the end of which hung a snare drum… I approached him and asked him for a picture. He instantaneously assumed a proud position and posed nicely, for which I gave him one of my last two cigarettes. Then he made a ruffle on the drums for about ten seconds, waited a half minute while the townspeople rolled out of the doors, and then announced something in rapid French…”

“…at the very end of the main street we found the town crier. He was very shabbily dressed in remnants of what may have been great glory in the past. Perhaps in peacetime he will recoup. He had on a faded blue shirt and old, dirty, black trousers. On his head a jaunty, if dusty, pillbox hat. Across his chest a leather strap… at the end of which hung a snare drum… I approached him and asked him for a picture. He instantaneously assumed a proud position and posed nicely, for which I gave him one of my last two cigarettes. Then he made a ruffle on the drums for about ten seconds, waited a half minute while the townspeople rolled out of the doors, and then announced something in rapid French…”

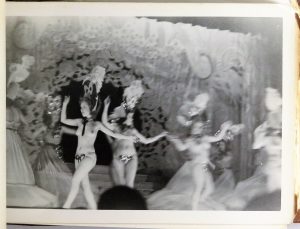

Dalton described post-liberation Parisian diversions; Dalton and Pete navigated a black market currency exchange in a “disreputable café”, attended a burlesque show in Pigalle (capturing two images of the topless and feathered dancers), saw an Agatha Christie play (“Ten Little Niggers”), and witnessed a fire dancer at an Officer’s Club.

Dalton described post-liberation Parisian diversions; Dalton and Pete navigated a black market currency exchange in a “disreputable café”, attended a burlesque show in Pigalle (capturing two images of the topless and feathered dancers), saw an Agatha Christie play (“Ten Little Niggers”), and witnessed a fire dancer at an Officer’s Club.

Continuing east, Dalton paints a vivid picture of the devastation left behind by the war. “Following the coast line we began to see names that we had seen many times in the papers after D Day. Trouville, Villerville, Deauville.” He becomes a discerning connoisseur of carnage: “There are differences in wreckage. The wreckage of bombing seems almost gentler than that by shelling… You can see that Caen was shelled.”

While exploring a bombed church in Alsace-Lorraine, Dalton and Pete encountered a German-speaking priest, “a burly character with a days growth of beard too many…”

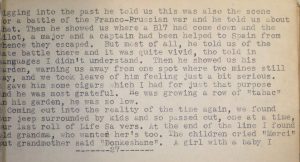

“… he told us all about the battle there… He took us into his backyard and showed us the foxholes the Americans had used. I felt quite humble as he picked up some cartridge cases, cases that had been fired against Germans. A gas mask lay by the field a Sherman tank lay blasted… Digging into the past he told us this was also the scene for a battle of the Franco-Prussian war… Then he showed us where a B17 had come down… But most of all, he told us of the late battle there and it was quite vivid… he showed us his garden, warning us away from one spot where two mines still lay… I gave him some cigars… and he was most grateful. He was growing a row of “tabac” in the garden, he was so low. Coming out into the reality of the time again, we found our jeep surrounded by kids and so passed out, one at a time, our last roll of Life Savers. At the end of the line I found old grandma, who wanted her’s too. The children cried “Merci” but grandmother said “Donkeshane”… we climbed into the jeep and slowly drove away… caught between two countries whose fate has been one war after another.”

“… he told us all about the battle there… He took us into his backyard and showed us the foxholes the Americans had used. I felt quite humble as he picked up some cartridge cases, cases that had been fired against Germans. A gas mask lay by the field a Sherman tank lay blasted… Digging into the past he told us this was also the scene for a battle of the Franco-Prussian war… Then he showed us where a B17 had come down… But most of all, he told us of the late battle there and it was quite vivid… he showed us his garden, warning us away from one spot where two mines still lay… I gave him some cigars… and he was most grateful. He was growing a row of “tabac” in the garden, he was so low. Coming out into the reality of the time again, we found our jeep surrounded by kids and so passed out, one at a time, our last roll of Life Savers. At the end of the line I found old grandma, who wanted her’s too. The children cried “Merci” but grandmother said “Donkeshane”… we climbed into the jeep and slowly drove away… caught between two countries whose fate has been one war after another.”

They continued through Belgium and Luxembourg. Dalton’s comments show him curious and observant, but also clearly marked by the bitter sentiments of a soldier who has lost time, hearth, and comrades to an unforgiven foe. Passing into Germany Dalton notes “we didn’t pause here, and to celebrate the new country for my lighter, I merely spat out the window.” In Germany, Dalton observed the devastation one would expect to find in August 1945: “The route from Homburg to Ludwigshaved is so littered with the wreckage of armored armies that it is nigh indescribable. Almost bumper to bumper, and in many places several deep, the carcases of trucks, cars, and tanks line the way.” Later, observing “burned-out tanks, Bren gun carriers, trucks, etc., all along way” Dalton says – perhaps inadvertently laconic and symbolic – “Occasionally they had been gathered into piles for salvage, but for the most part they lay as they died. The farmers carefully plowed around them.

They continued through Belgium and Luxembourg. Dalton’s comments show him curious and observant, but also clearly marked by the bitter sentiments of a soldier who has lost time, hearth, and comrades to an unforgiven foe. Passing into Germany Dalton notes “we didn’t pause here, and to celebrate the new country for my lighter, I merely spat out the window.” In Germany, Dalton observed the devastation one would expect to find in August 1945: “The route from Homburg to Ludwigshaved is so littered with the wreckage of armored armies that it is nigh indescribable. Almost bumper to bumper, and in many places several deep, the carcases of trucks, cars, and tanks line the way.” Later, observing “burned-out tanks, Bren gun carriers, trucks, etc., all along way” Dalton says – perhaps inadvertently laconic and symbolic – “Occasionally they had been gathered into piles for salvage, but for the most part they lay as they died. The farmers carefully plowed around them.

In Austria, while changing a particularly stubborn flat with help from the locals, Dalton observed: “I had a good chance to talk to these people. We talked, of course, mostly about the war, and I found that what others are finding is true: it is always someone else to blame, never the person you are talking to. The Fraulein had lost a brother at Stalingrad and her fiancée in France and was quite sorry. Her father she had not heard from since March. I found myself sympathizing with her until I caught myself and started questioning her about Hitler.”

A more philosophically unforgiving Dalton also observes of the Austrians: “They had only the choice of accepting or being killed or put in a concentration camp, so that they made the best of a bad thing… I left but in leaving thought: “Is life so dear or peace so sweet that it must be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?”

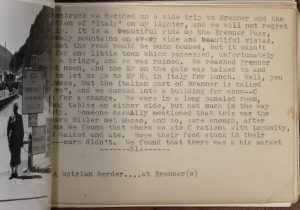

Where there are glints of sympathy for the volk, there is none for those who led them to war. Crossing into Italy via the Brenner Pass, Dalton noted: “Someone casually mentioned that this was the room where Hitler met Musso, and so, sure enough, after questions we found that where we ate C rations with impunity, H and M talked and ate. Hope their food stuck in their craws – ours didn’t.”

Where there are glints of sympathy for the volk, there is none for those who led them to war. Crossing into Italy via the Brenner Pass, Dalton noted: “Someone casually mentioned that this was the room where Hitler met Musso, and so, sure enough, after questions we found that where we ate C rations with impunity, H and M talked and ate. Hope their food stuck in their craws – ours didn’t.”

Despite the hardened perspectives that understandably informed and colored what Dalton saw, it is clear from his images and prose that the journey was affecting. In the final pages of his narrative, Dalton enigmatically writes: “…so good that we are thinking – just thinking – that maybe – well, we shall see.”

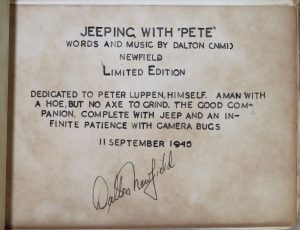

The book opens with Dalton’s carefully printed and signed title page and dedication:

WORDS AND MUSIC BY DALTON (NMI)

NEWFIELD

LIMITED EDITION

DEDICATED TO PETER LUPPEN, HIMSELF. A MAN WITH

A HOE, BUT NO AXE TO GRIND. THE GOOD COM-

PANION, COMPLETE WITH JEEP AND AN IN-

FINITE PATIENCE WITH CAMERA BUGS

11 SEPTEMBER 1945

Below the date is Dalton’s autograph.

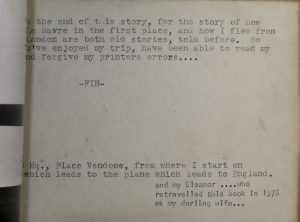

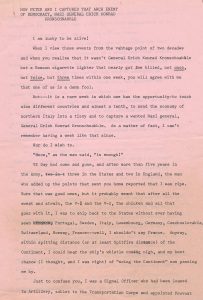

At the end of Dalton’s narrative, below the word “FIN”, Dalton typed a postscript:

“From ATC Hq., Place Vendrome, from where I start on the bus which leads to the plane which leads to England.

“From ATC Hq., Place Vendrome, from where I start on the bus which leads to the plane which leads to England.

Just below that postscript, a second postscript, in different type evidently added later:

“and my Eleanor ….who

retravelled this book in 1978

as my darling wife…”

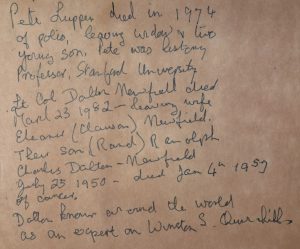

Dalton Newfield took from wartime Europe not only an abiding respect for Churchill, but also an English bride. The final page of the book is a holograph postscript in the hand Dalton’s wife, Eleanor:

of polio, leaving widow & two

young son. Pete was history

Professor, Stanford University.

Lt Col Dalton Dalton Newfield died

March 23 1982 – leaving wife

Eleanor (Clauson) Newfield.

Their son (Rand) Randolph

Charles Dalton-Newfield

July 25 1950 – died Jan 4th1959

of cancer.

Dalton known around the world

as an expert on Winston S. Churchill.

We also include two additional photographs, of Dalton Newfield and Peter Luppen, which were found laid into the book, as well as eleven pages of what appears to be a later, unfinished, type-written attempt by Newfield to fictionalize the narrative.

It has been a pleasure and a privilege for us to review, relive, and relate the singular perspective and experiences compiled in this singular little book. We look forward to relinquishing “Jeeping with Pete” to the stewardship of a new collector, ensuring the preservation and continued appreciation of the vivid and intimate vignettes therein.

It has been a pleasure and a privilege for us to review, relive, and relate the singular perspective and experiences compiled in this singular little book. We look forward to relinquishing “Jeeping with Pete” to the stewardship of a new collector, ensuring the preservation and continued appreciation of the vivid and intimate vignettes therein.

One thought on “Jeeping with ‘Pete’ – a remarkable and truly singular portrait of Europe in August 1945”