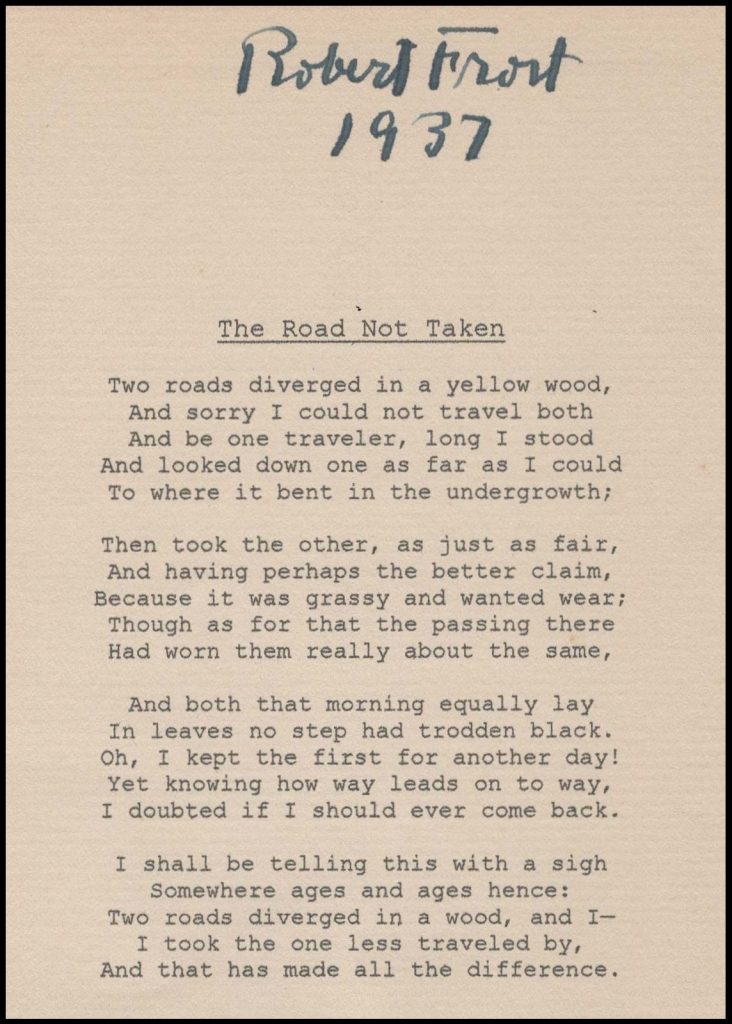

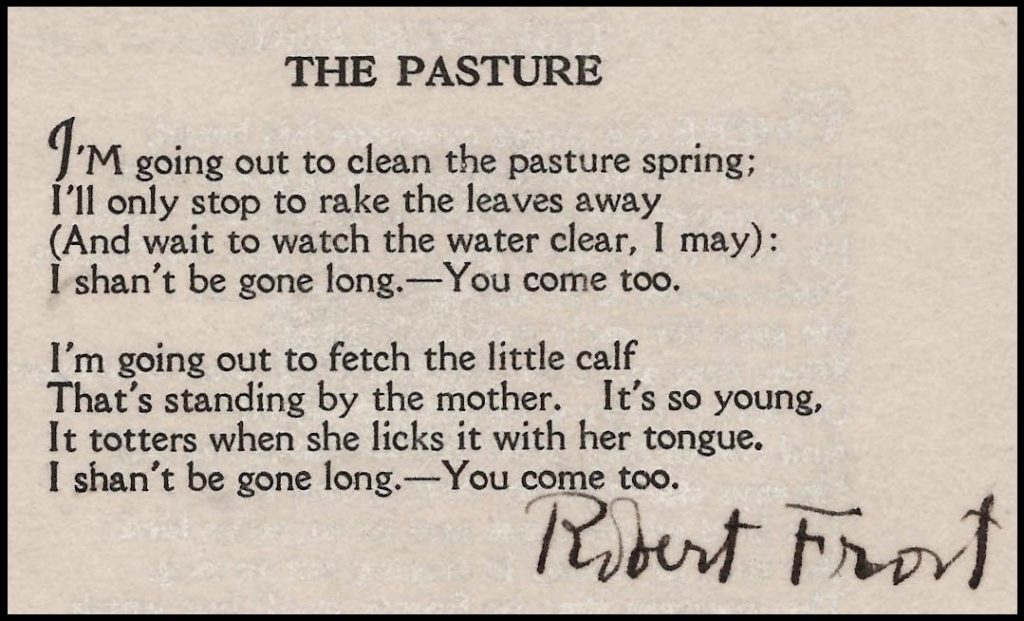

We are excited to release our new catalogue, which focuses entirely on iconic American poet Robert Frost. You may download the full catalogue by clicking HERE or on any of the images in this post

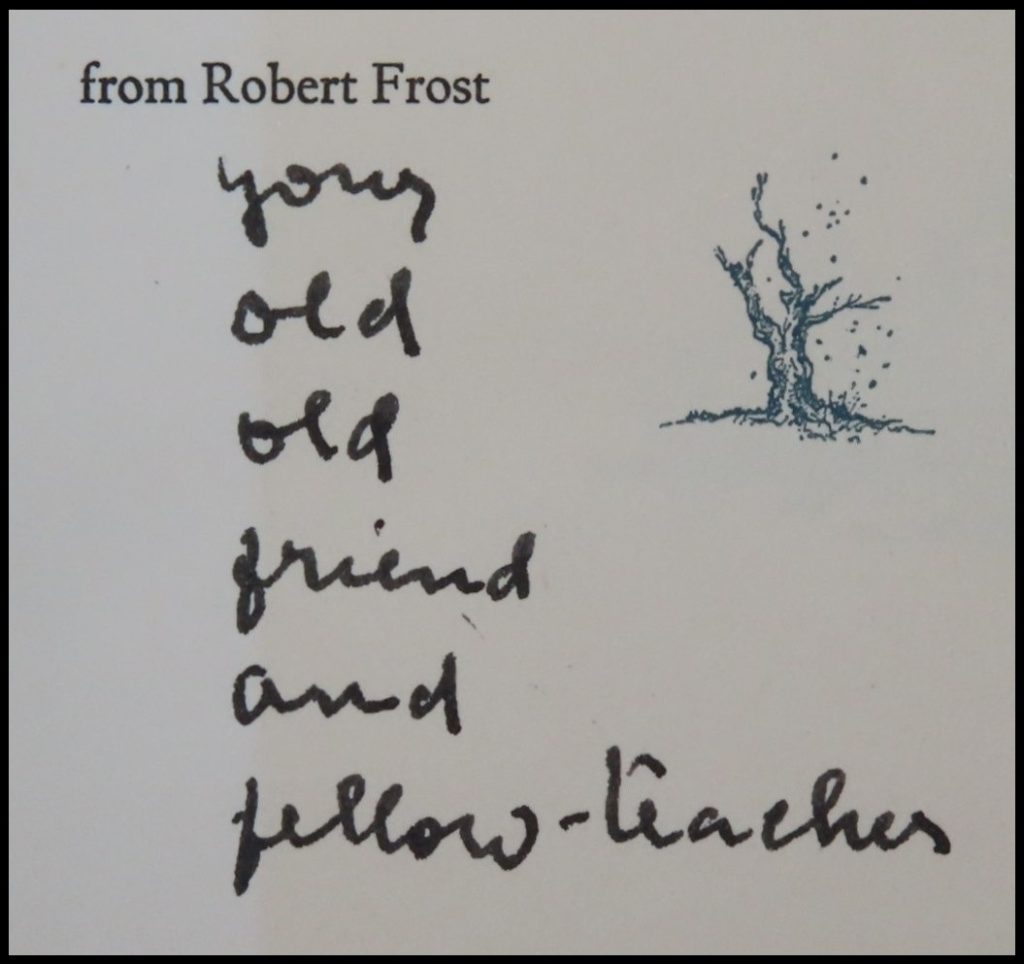

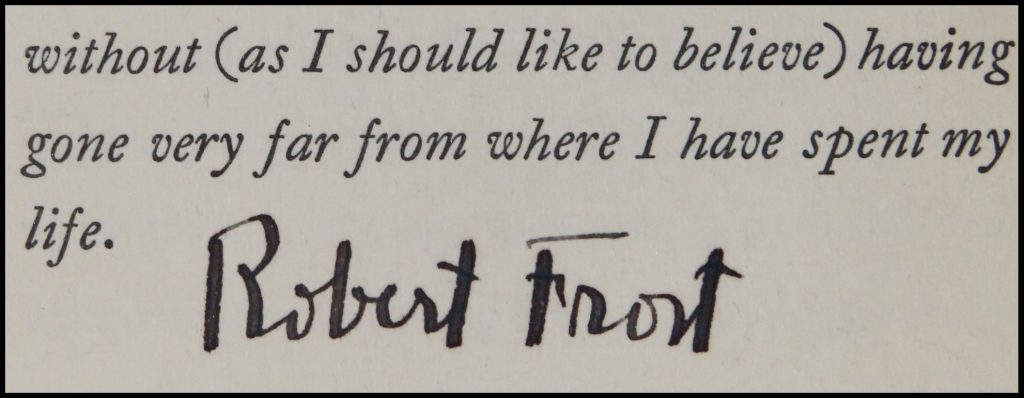

Assembling the trove of Robert Frost material in this catalogue was the work of decades. Herein, 71 items signed or inscribed by Frost, spanning his first to his final published work – including nearly three quarters of the bibliographer’s “A” list1 of his books and pamphlets published during his lifetime. And, of course, more besides, including signed letters, Christmas cards, manuscript and souvenir poems, and even a legal document.

Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry four times (1924, 1931, 1937, and 1943), a feat still unrivalled to this day. He spent the final decades of his life as “the most highly esteemed poet of the twentieth century” with an accumulating hoard of academic and civic honors, including honorary degrees from more than forty colleges and universities. (So many that the various academic hoods that came with the degrees were sewn together to make a quilt! And leading Frost, who never graduated from college, to quip “I got my education by degrees.”) Two years before his death, Frost became the first poet to read at the inauguration of a U.S. President. (Yes, back when American presidents were literate…)

But that’s just biography.

In a 15 November 1930 lecture called “Education by Poetry,” Frost said that “Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.” As it happens, this is also a functional definition of irony, and the life of Robert Frost contained some delicious ironies.

The quintessential poetic voice of New England was actually born in San Francisco. And this great Yankee poet, Robert Lee Frost, owes his middle name to his father’s hero, Robert E. Lee, the General-in-Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States during the Civil War. (No surprise that you’ll not see his middle name in his signatures – except for Item 48 in this catalogue.)

Then there’s England – the old one, not New. This iconic American poet had to move to England to achieve publication and recognition. Only after his first two books were published in England did Henry Holt and Company agree to publish his books in America. Holt would proudly remain his American publisher for the rest of his life.

And there’s the middle-aged man with a boy’s will. Frost was nearly forty years old before his first collection of poetry (A Boy’s Will, 1913) was published. Despite this late start, he would get to enjoy half a century of increasing and, eventually, unequalled fame and recognition.

Frost is often recognized for his accessible language and command of colloquial speech. Both were an intentional affectation, belying not only the complexities of his conceptions, but also the remarkable erudition and “fierce intelligence” of a man who spent decades lecturing and teaching at some of America’s most elite colleges and universities.

How does Yankee diction and purported provincialism square with Frost’s enduringly broad appeal? New England is a launching point, not a limitation. Frost’s apparent parochialism is exhaustively expansive. “New England is taken as representative… Frost moves through the local into the universal.”2 Or, as a fellow poet wrote, one sees in Frost’s work “Universal experience, portrayed concretely, in locality, in Yankee accent.”3

And sentiment. So well-known and beloved are many of Frost’s poems that we quote them to one another to express our feelings, amplify our own experience of love and loss. Yet Frost conspicuously avoided personal sentimentality in his poetry, which is often curiously, beautifully aloof. “Something in me refuses… to use grief for literary purposes. When I care less, I can do more.” Frost’s poetry is capable of deeply touching its readers, and yet you will not find poems about his father’s alcoholism, his sister’s and children’s mental illness, the death of his wife from cancer, and the deaths of four if his six children from cholera and childbirth and suicide.

Here, in Southern California, just reading Robert Frost can seem an exercise in irony. Here it’s likely that the only precipitation a big winter coat will endure is sweat. And kicking palm fronds in your sandals is just not the same as shuffling booted feet through mounds of mouldering leaves. But even if our woods here are never “lovely, dark and deep”, there is Robert Frost. His New England provides us with culturally universal visions of reaving and renewing, of all seasons, literal and figurative. And Frost remains the elemental poetic voice of these seasons, the “wind’s will” synonymous with “A boy’s will,” baring branches with brisk, gusting whorls of ink and leaving crisp, listening silences between.

May you enjoy perusing this catalogue as much as we enjoyed compiling it. More important, may you grant yourself the gift of some time with Frost’s words and perspective.

Cheers!

1 Joan St. C. Crane, Robert Frost: A Descriptive Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts, A1-A42

2 Jay Parini, Robert Frost: A Life

3 “Genevieve Taggard, Robert Frost, Poet,” New York Herald Tribune Books 30 November 1930