So today we’re writing about a don’t. Something we don’t do, something we hope you don’t do either, and things we *really* wish others hadn’t done.

The unifying theme is stewardship. You may have heard me cheekily assert that, even when you pay us a lot of money for a precious item, you don’t own it.

Yep. That’s right. As a professional bookseller I’m asking you to pay lots of money for precious objects and then telling you that you don’t own what you bought.

Perhaps I should clarify before I hear from your attorney. I encourage you not to regard such things as if you own them. I respectfully suggest that your job as a discerning collector is to make sure your collection outlives you and your custody thereof. Relish, of course. Covet, obsess and even, if you must, brag a little. But foremost serve as a diligent and conscientious custodian. Take care to preserve what is in your custody. And make sensible provisions to ensure that your charges find a successor custodian with commitment and sensibility equal to your own.

Stewardship informs our don’ts.

Beyond the fairly straightforward considerations of preservation (see our How to Protect Your Collection post), if we can prosthelytize one prime directive, this is it:

Don’t write in the book unless you wrote the book!

Why? Because it’s not about you.

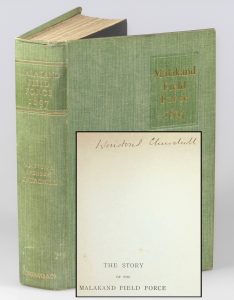

The Story of the Malakand Field Force… and Who?

Some years ago, we were delighted to discover a first edition, first state of Churchill’s first published book not only in exceptional condition, not only signed by Churchill, but with provenance indicating that it was signed during his first American lecture tour. It had remained in the same family until acquired by the collector from whom we, in turn, acquired it.

The book was just gorgeous inside and out in all but one respect. The most recent owner had pasted his own bookplate on the verso of the signed page. A modern bookplate, composed of non-archival paper and ink, and affixed with non-archival adhesive. This gracious, kind, otherwise decent gentleman had defaced something that had miraculously survived over 100 years, virtually unscathed. I couldn’t help asking him: “Why?” He paused before he replied “Well, I thought people might want to know who owned it before.”

The man has since died. He was uncommonly courteous and urbane and I genuinely enjoyed his company – as I expect did many who knew him. And he loved books. Nonetheless, this book left his stewardship poorer than it entered. Assuming the good offices of the current and future stewards, I expect the only question the bookplate will prompt in the future years is “Who was this guy?” Followed swifty by “Why the F@%$ …?”

There’s worse. Much worse.

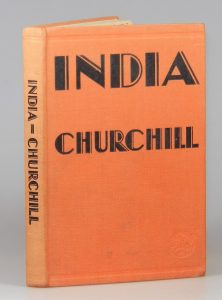

9021Ohno!

India is one of Churchill’s more scarce and obscure works of his 1930s wilderness years. Hardcover issues of the two printings of the first edition are scarcer still. Positively rare – even extravagantly rare – are signed or inscribed copies.

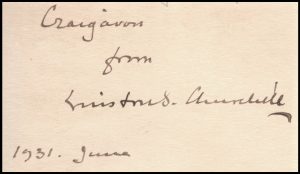

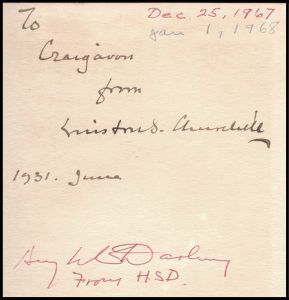

So imagine our delight at discovering a hardcover first edition, second and final printing inscribed by Churchill within weeks of publication to James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon of Stormont and first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. Not just signed, but inscribed and dated. Not just inscribed and dated, but an important association. And not just any association but one splendidly charged with irony given the book in question. Churchill vigorously opposed Indian independence on the grounds that it would unleash the destructive potential of religious strife, lead to bitter partition and disputed borders, and unleash sectarian violence. Churchill came to support Irish Home Rule – which entailed both a bitter partition and fueled the ensuing better part of a century of sectarian violence and territorial disputes. James Craig was a vehement opponent of Irish independence, though he became the first Prime Minister for Northern Ireland and worked – closely with Churchill – to ensure the viability and perpetuation of a self-governing Northern Ireland.

Wow, right?

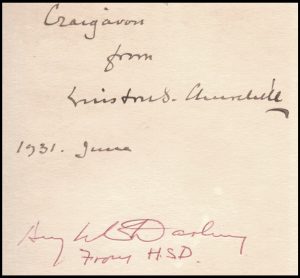

Here’s the rub. One of the “stewards” of this book had been a former mayor of Beverly Hills. In a noteworthy act of vandalism, our mayor inked inked “Hugh W. Darling | From H.S.D.” one inch below Churchill’s gift inscription. “H.S.D.” is presumably Darling’s wife, Hazel, from whom Darling ostensibly received the book as a gift. This one might possibly be persuaded to pardon as the misplaced gratitude of a spouse.

Alas, Good Mayor Hypergraphia doubled down on the stupid, using the book as a reading copy in the late 1960s. Twice. Which we know because he dated each reading. On the inscribed page. And underlined liberally throughout at each reading in red and blue colored pencil.

Yeah.

You doubtless do not recognize the mayor’s name. Which, I suppose, is precisely the point. We just wish someone had told him “It’s not about you!” – and maybe bought his-and-hers coloring books for the couple instead.

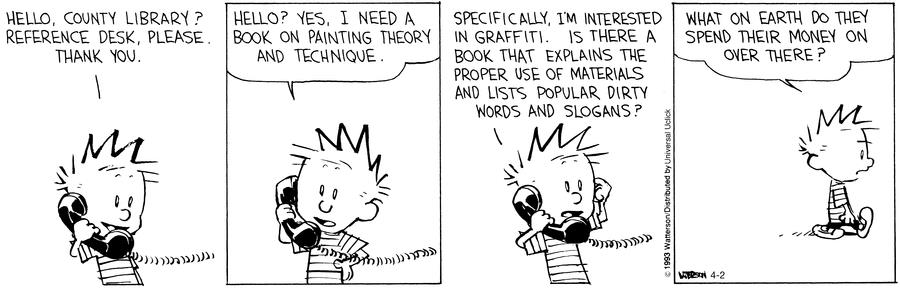

One might, of course, cite clever exceptions to our “Don’t write in the book unless you wrote the book” rule. If Alexander wanted to scribble on the scrolls of his tutor, Aristotle, and if we were lucky enough to inherit same, we wouldn’t complain. Likewise, nobody is bemoaning the recent discovery that a surviving Shakespeare First Folio bears John Milton’s annotations. You might even counter in less rarified fashion that archaeologists now take keen interest in Roman graffiti.

OK, fine. If you conquer the known world or pen Paradise Lost, then you can scribble away in your Gutenberg Bible. When you are 2000 plus years old, you can write graffiti on whatever you want. Until and unless, please, please don’t.

As any dog will show you, this urge to mark can be compelling.

“But it’s only pencil” you might say. Yes, but even erasing pencil can cause abrasion, loss, and tears.

“But I want to read it” you might say. Well, of course! So get a less precious reading copy and read it as many times as you want, annotating all the way.

I’ve read Hobbes’ translation of Thucydides several times since my early twenties. I cannot imagine reading it without annotating as I go. But my annotated copies are sufficiently humble in historical importance to be precious to nobody but me.

Every time you merely open a book, you kill it just a little. Books are a tenuous combination of perishable materials and discordant chemistry – paper and glue and string and cloth, material animal, vegetable, synthetic, or all three. The constituent elements of books court entropy and conspire to decohere almost from the moment they are bound together. As are the thoughts and sentiments that fill it, a book is a small miracle of ephemeral sentient alignment. For most books, their purpose is fulfilled in being read and wrecked.

But for the very few… Collectible books become a precious, lingering signal amid the static with the sole, fragile, lovely purpose of being regarded. The magic of rare books and ephemera is that often the longer they endure, the better they are regarded.

Protect and pass them on.

Cheers!

5 thoughts on “(Please) Don’t!”