Much ink has been spilled on the relationship between Winston S. Churchill and his father, Lord Randolph Churchill. Churchill’s inclination to great reverential respect for his father seemed proportional to the cold distance Randolph held between them during his short life. But reverence was not obedient piety; Winston’s respect for his father did not prevent his developing his own perspectives on public policy during a political career which proved far longer, accomplished, and consequential than that of his father. Home Rule for Ireland is a case in point, underscored by an historically consequential letter we recently had the good fortune to handle, and which anchors and informs this post.

The letter is the infamously incendiary 7 May 1886 anti-Irish Home Rule declaration by Lord Randolph Churchill, containing and coining the rallying cry “Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right”. Excerpts from this letter were published the next day in The Times of London, fanning sectarian hatred and violence, and helping defeat the first attempt to grant Ireland self-government within the United Kingdom. The final, successful attempt would be pushed through Parliament by Randolph’s son, 36 years later.

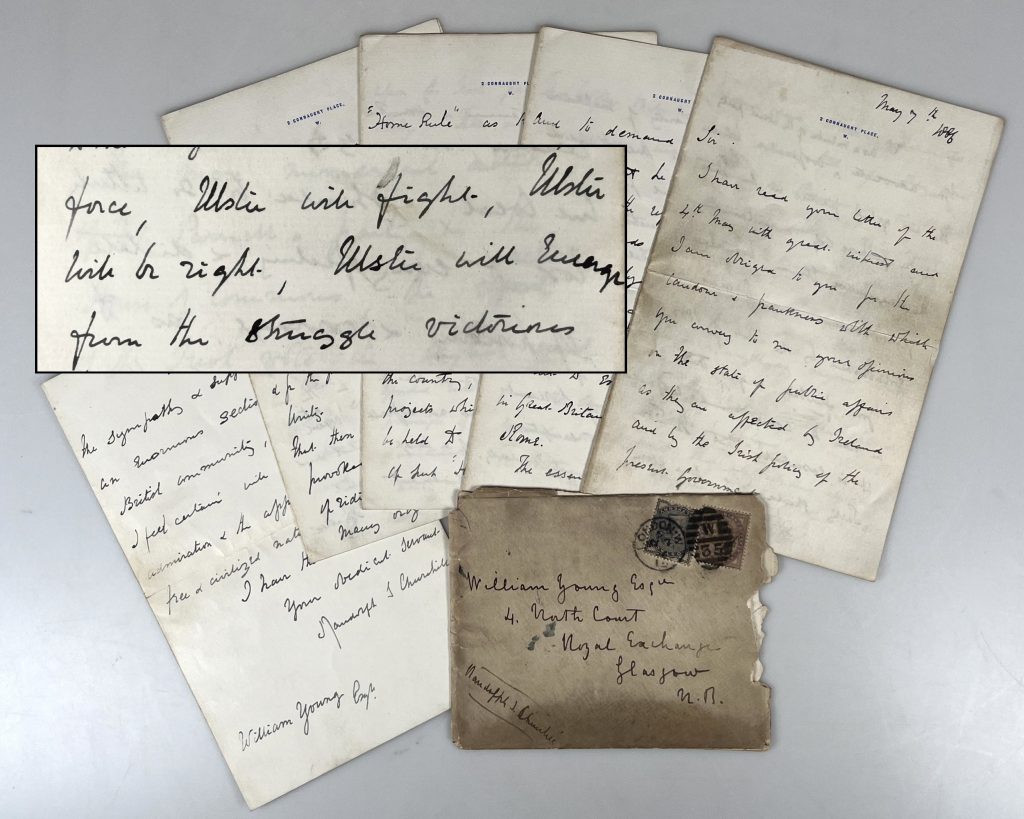

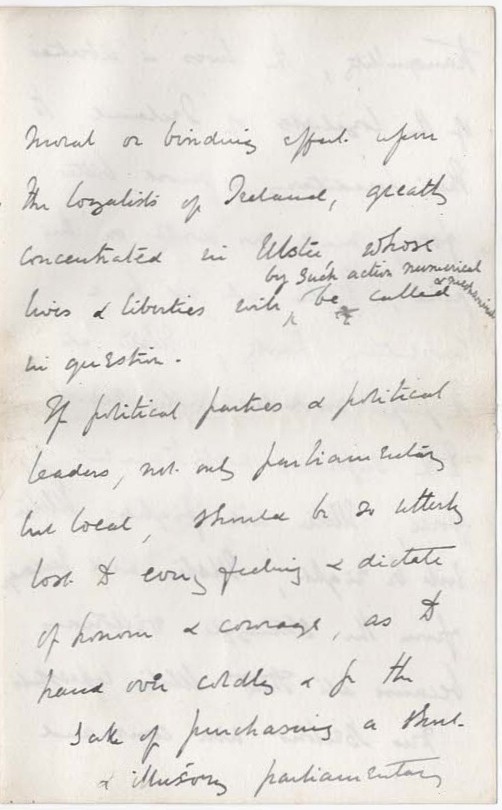

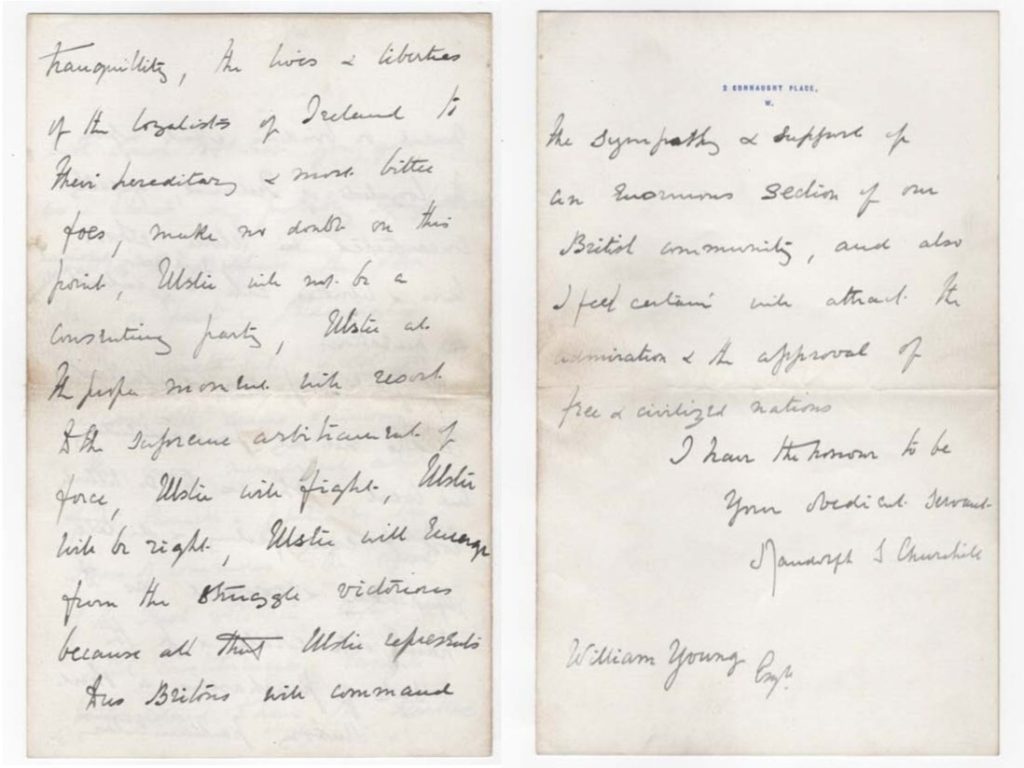

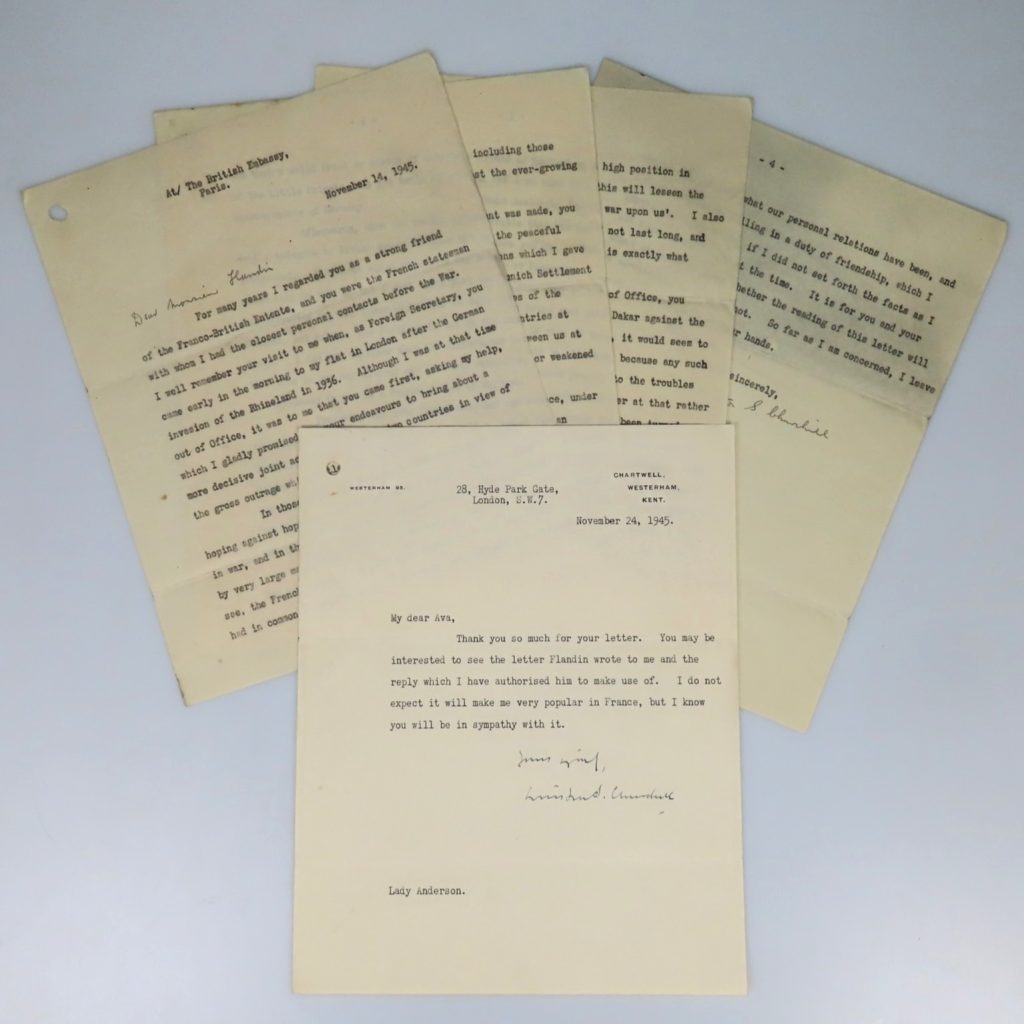

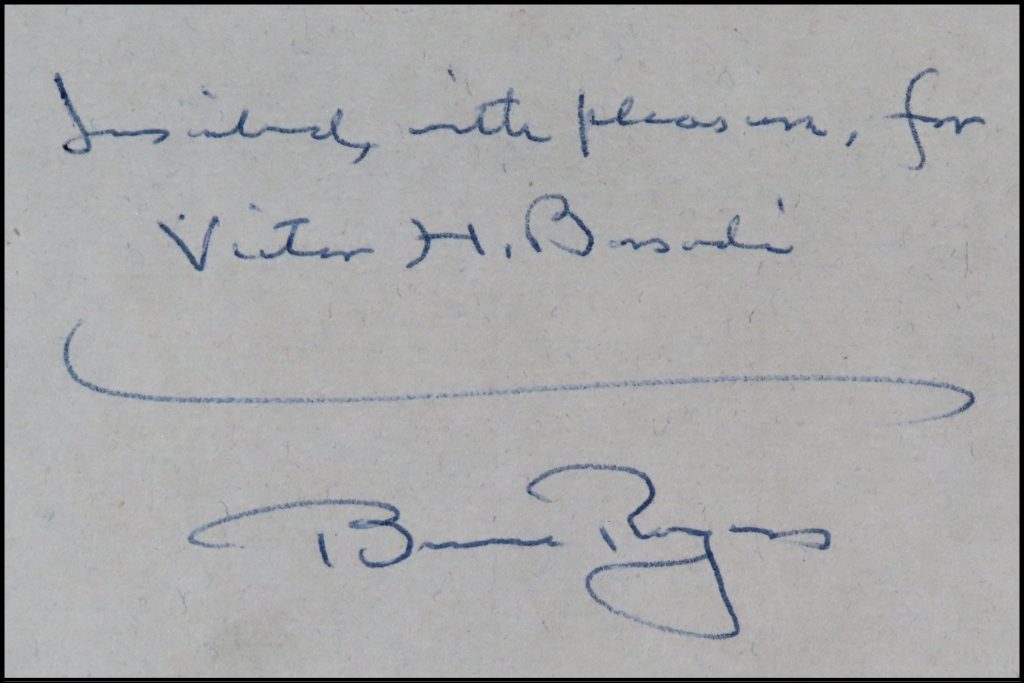

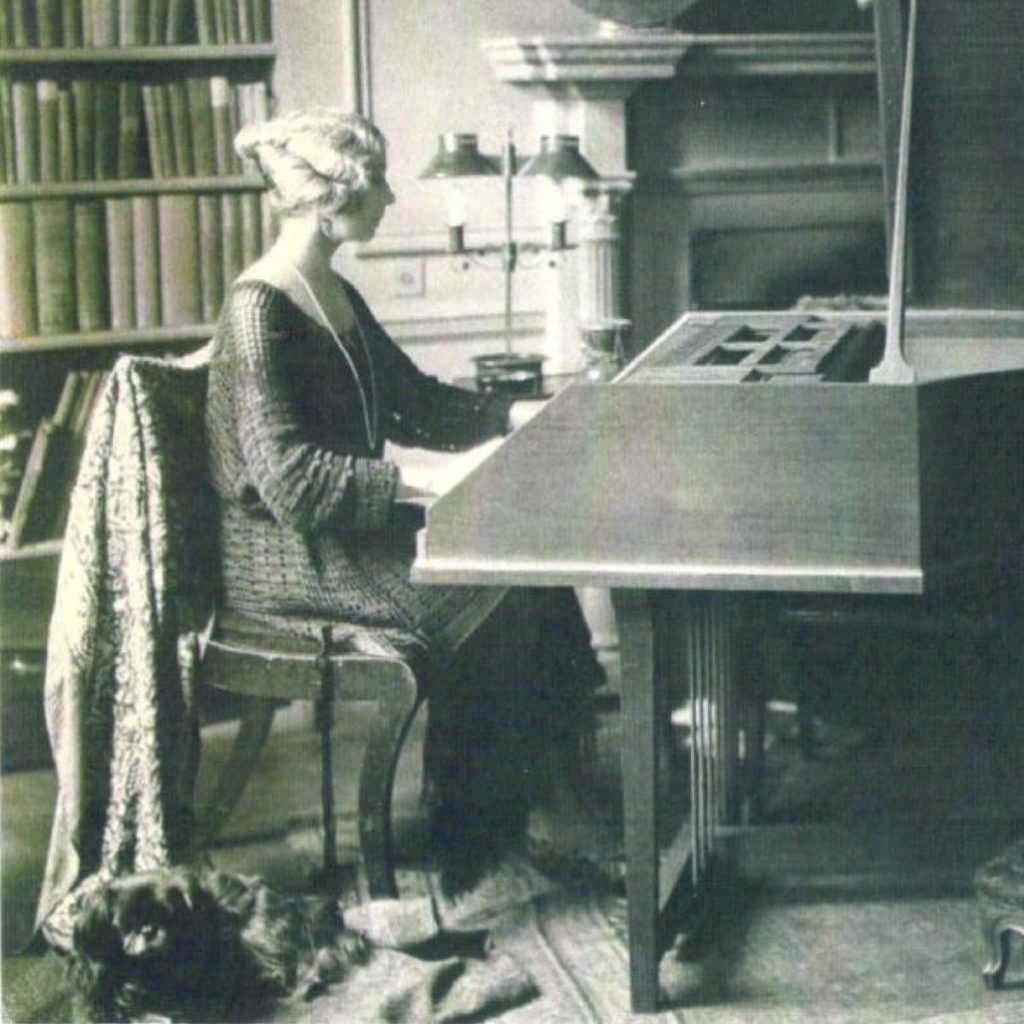

It’s a lengthy letter, written entirely in Lord Randolph Churchill’s hand, on five 8 x 10 inches sheets of his “2 Connaught Place, W.” stationery, each sheet folded to form four 8 x 5 inches panels. Lord Randolph’s letter fills 17 panels. The letter is accompanied by the original, franked, “2 Connaught Place” envelope, hand-addressed to the recipient’s Glasgow address and signed “Randolph S. Churchill”.

Items often come to us shorn of knowledge about their ownership sojourn. In this case, we know at least quite a number of recent decades of stewardship; this letter was part of the Forbes family’s incomparable Churchill collection, thereafter part of the Churchill collection of Richard C. Marsh, from whence it came to us. Given the letter’s significance, it is no surprise that it was sought by such discerning collectors and part of such significant Churchill collections. We’ll soon offer this letter for sale, giving a new steward the opportunity to step forward. But first, this post!

“Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right”

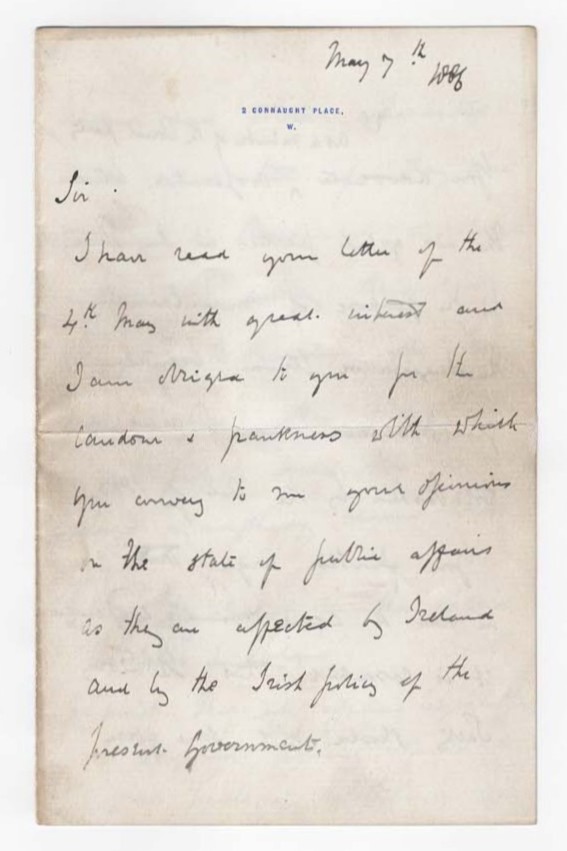

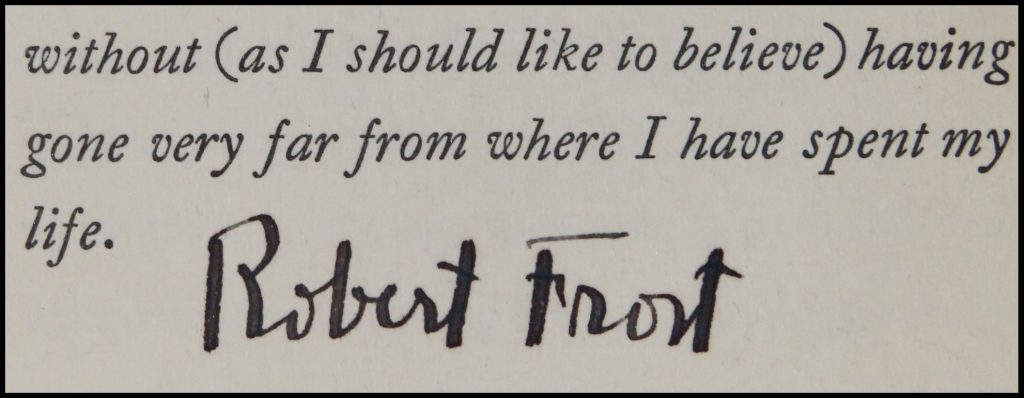

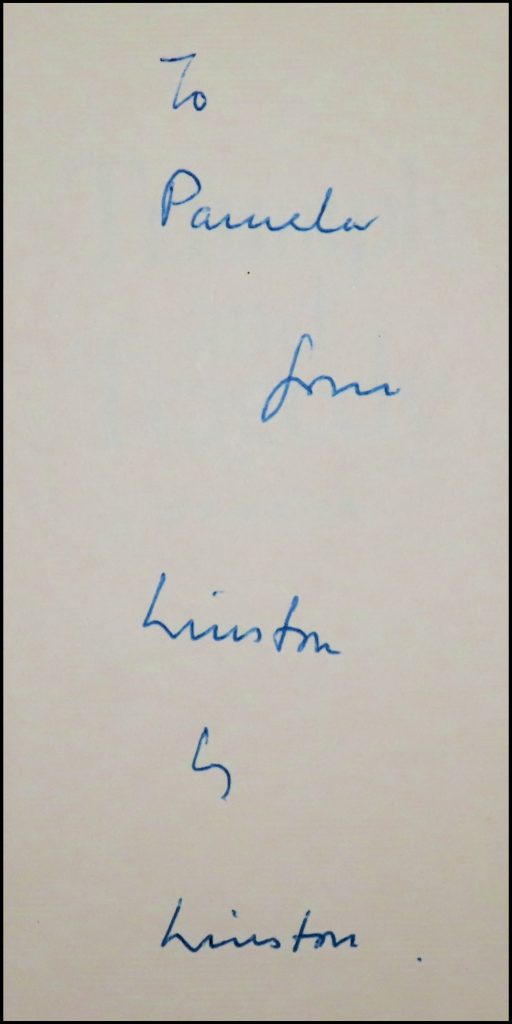

The letter is dated “May 7th 1886” at the upper right, begins with the salutation “Sir“, and reads thereafter: “I have read your letter of the 4th May with great interest and I am obliged to you for the candour & frankness with which you convey to me your opinions on the state of public affairs as they are affected by Ireland and by the Irish policy of the present Government.”

There is plenty of substance to note. Some highlights include:

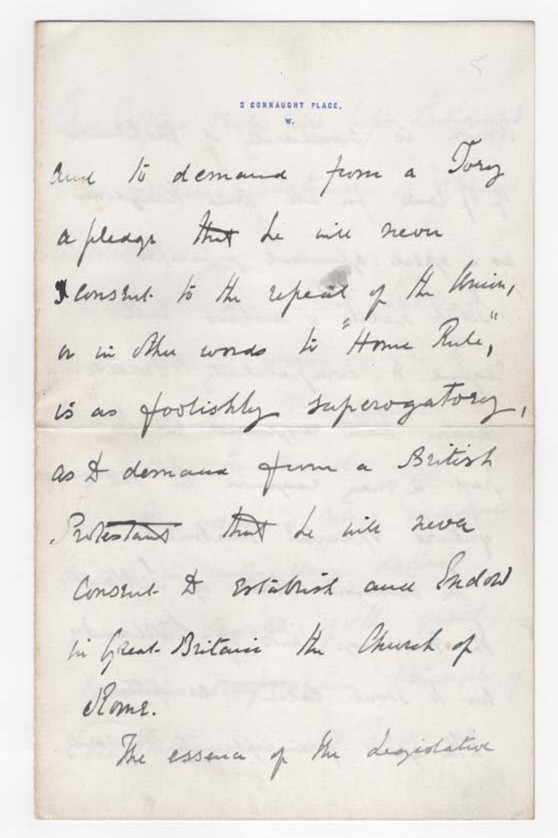

“…to demand from a Tory a pledge that he will never consent to the upset of the Union, as in other words to “Home Rule,” is as foolish superogatory, as to demand from a British Protestant that he will never consent to Establish and Endow in Great Britain the Church of Rome.”

“…Irish habits & customs may from time to time call for exceptional Legislative treatment. But these rare & minor incidents do not in any way detract from the sanctity of the great general overpowering principle of One Parliament one Law for the United Kingdom.”

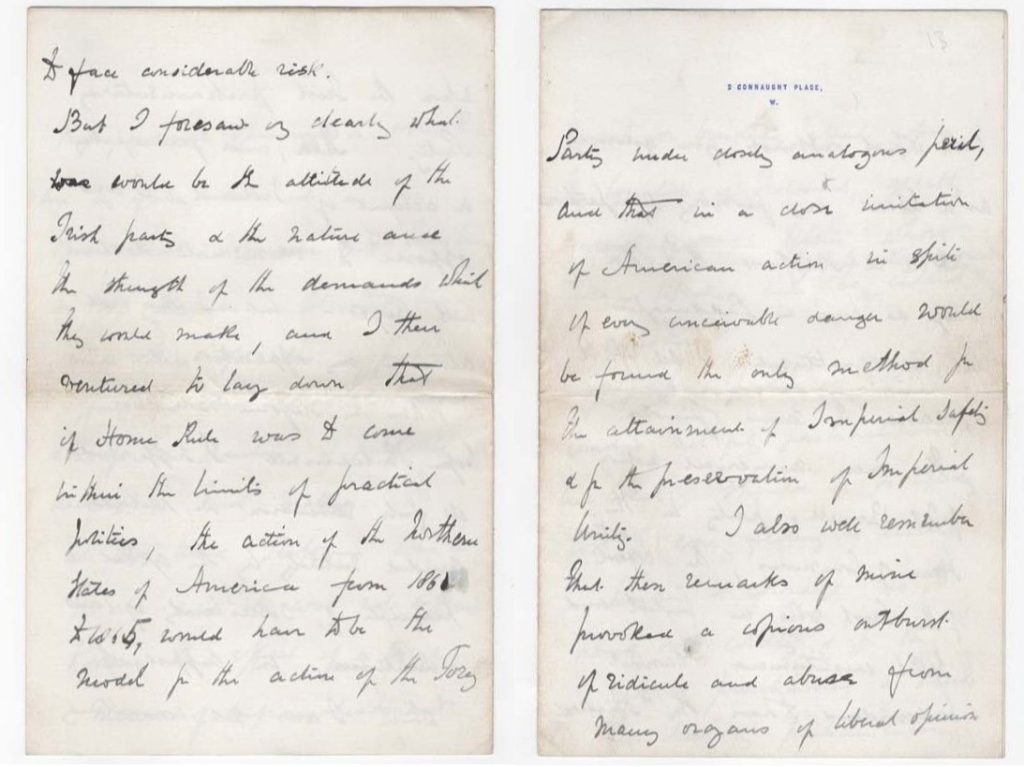

Lord Randolph asserted that if Home Rule managed to become law, “the action of the Northern States of America from 1861 to 1865 would have to be the model for the action of the Tory Party under closely analogous peril, and that in a close imitation of American action in spite of every conceivable danger would be found the only method for the attainment of Imperial safety & the preservation of Imperial Unity.”

The referential justification of civil war would seem rhetorically charged on its own, but it is in the middle of the 15th page/panel that the fireworks really start. This is where the letter’s famously inflammatory peroration begins:

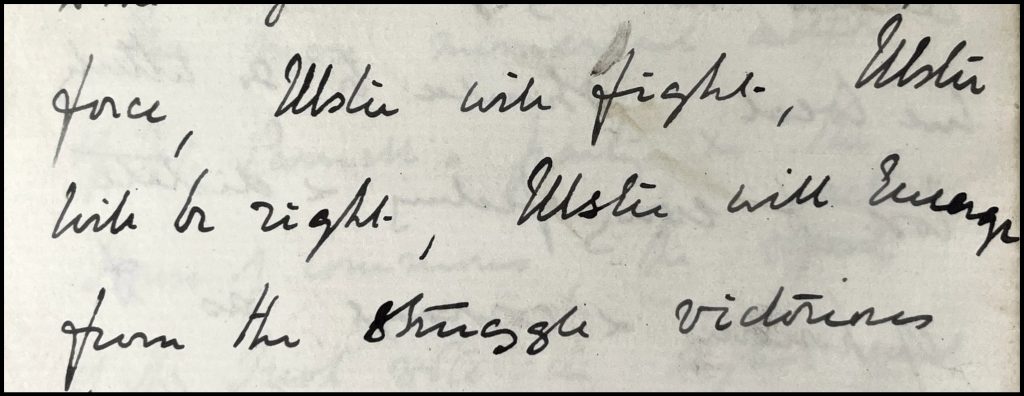

“If political parties and political leaders, not only Parliamentary but local, should be so utterly lost to every feeling & dictate honour & courage, as to hand over coldly, & for the sake of purchasing a short & illusory parliamentary tranquility, the lives & liberties of the Loyalists of Ireland to their hereditary & most bitter foes, make no doubt on this point, Ulster will not be a consenting party, Ulster at the proper moment will resort to the arbitrament of force, Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right, Ulster will emerge from the struggle victorious because all that Ulster represents to us Britons will command the sympathy & support of an enormous section of our British community, and also I feel certain will attract the admiration and the approval of free & civilised nations.“

The letter terminates with the two-line valediction “I have the honour to be | your obedient servant” followed by Lord Randolph’s signature “Randolph S. Churchill“. Professed obedient servitude is, of course, deeply ironic; this is not a trait for which either Randolph or his son is best remembered.

The moment

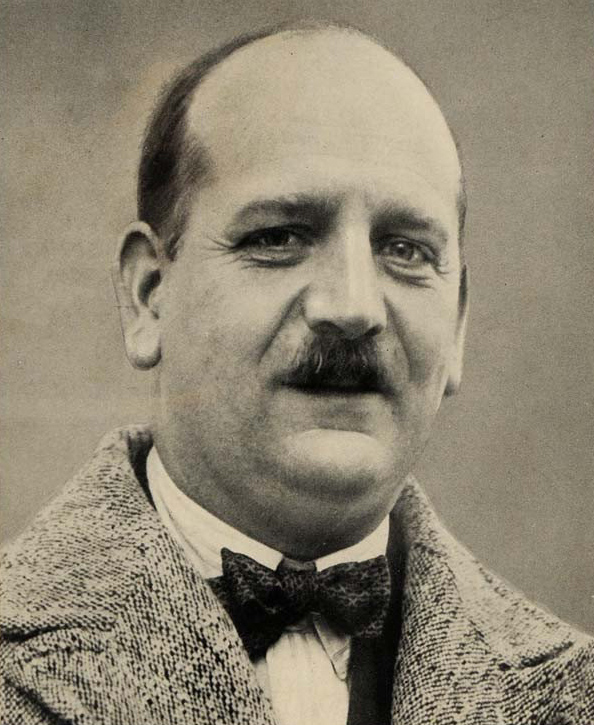

In 1886, Lord Randolph Churchill was a rising young force in his Conservative Party, shrewd, articulate, and influential, but an “awkward colleague” regarded by the head of his Party as possessed of a “wayward and headstrong disposition”. The narrow victory of the Liberals in the 1885 General election left them in need of support from Irish nationalists, causing Prime Minister Gladstone to espouse the policy of Home Rule. Lord Randolph “immediately appreciated the significance” and “decided to ‘play the Orange card’ – to exploit the strong opposition of Ulster Protestants to home rule.” In a fiery speech in Belfast in February 1886, Lord Randolph sought to rouse loyalist Protestant Orangemen of Northern Ireland. But it was in this published letter of 7 May 1886 to William Young that Lord Randolph committed even more volubly to his cause and truly fanned political flames.

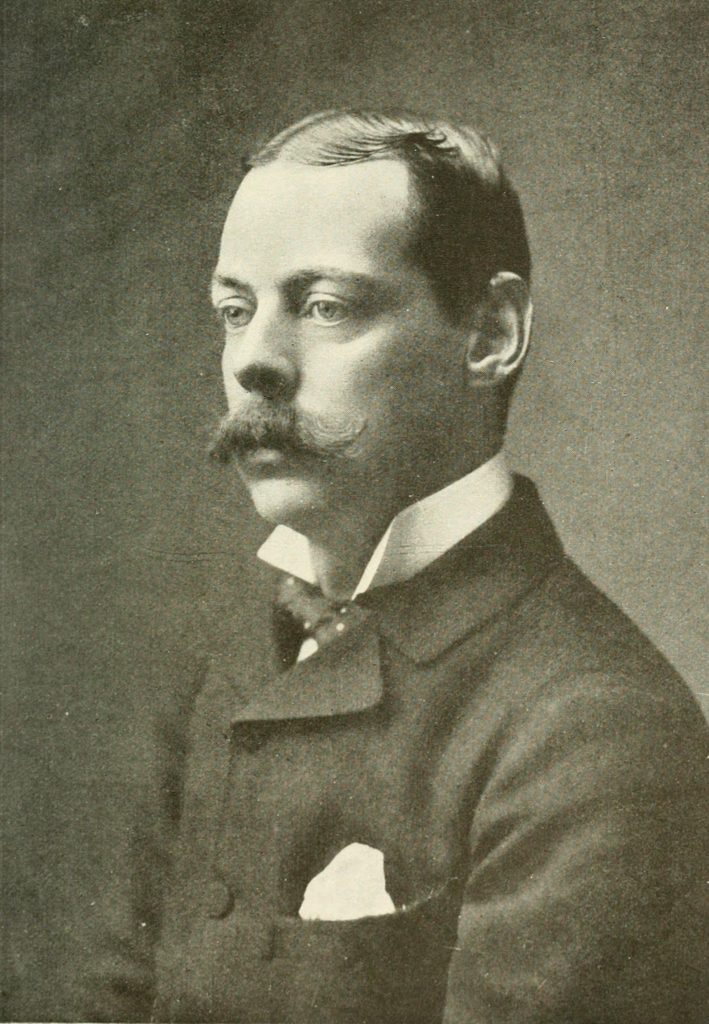

A Scottish Liberal-Unionist member of Parliament, William Young (1863-1942) had written to Lord Randolph on 4 May to demand that he pledge never to support Home Rule for Ireland. Lord Randolph replied in this 7 May 1886 letter. Lord Randolph’s letter was no mere reply, but rather a political set piece; excerpts of the letter were published in The Times of London the next day and “electrified the nation with its threat of violence.”

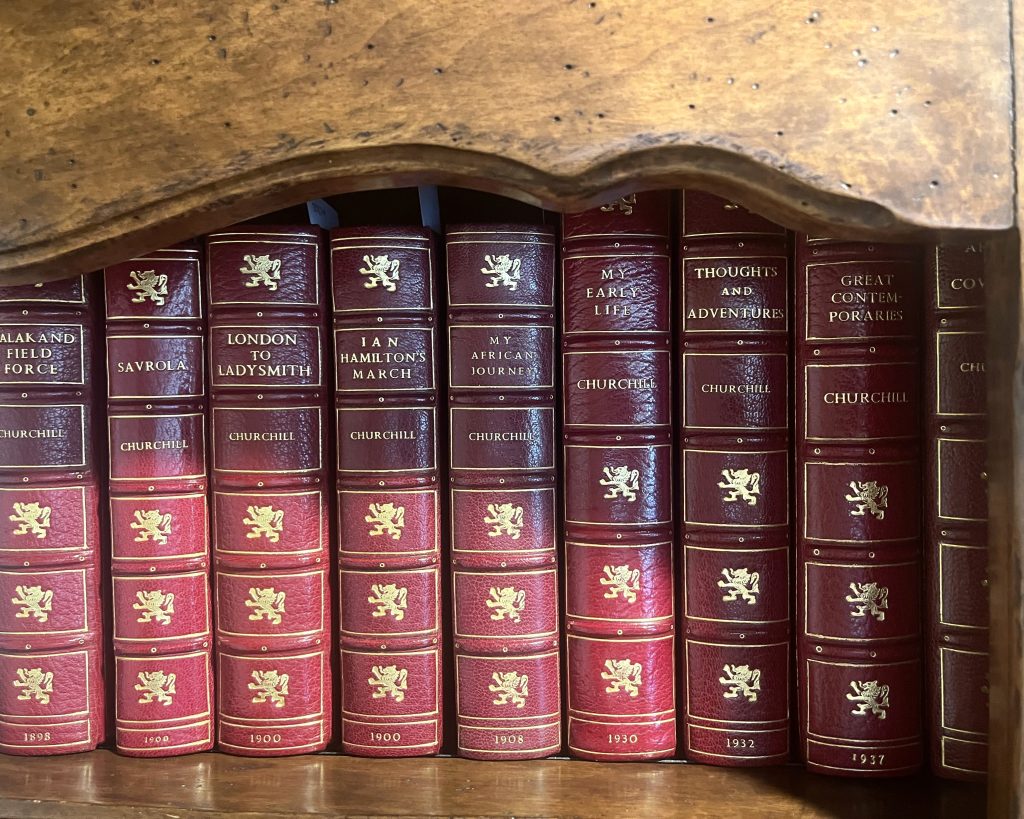

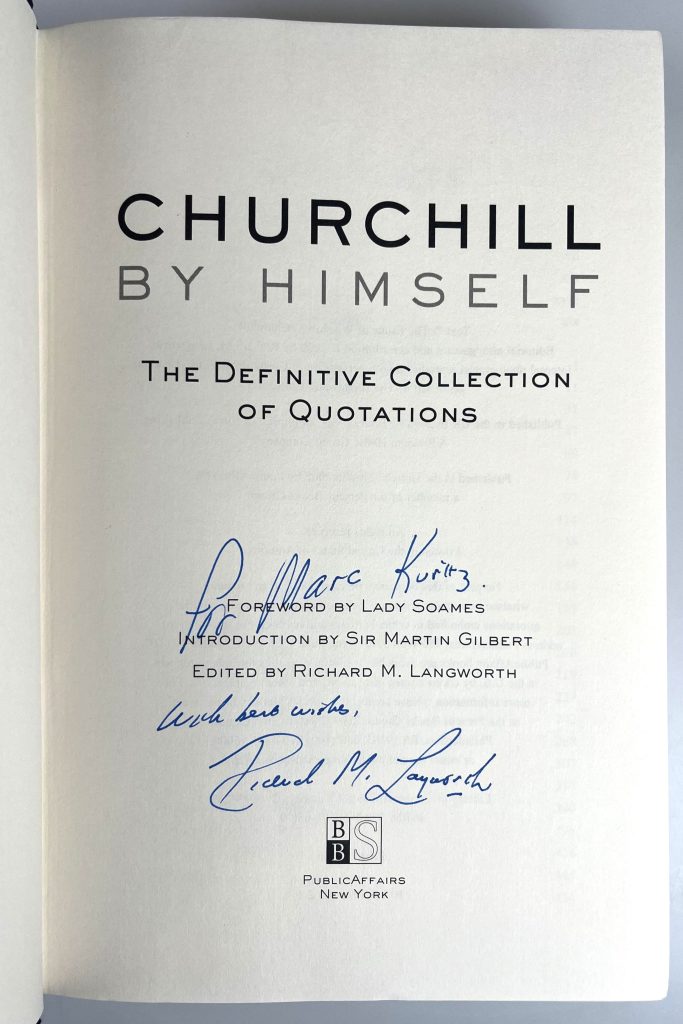

It is the peroration of this letter that (altered only by salutary insertion of appropriate punctuation), Winston S. Churchill quoted at p.65, Volume II, of his 1906 biography of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill. In late April, Lord Randolph was facing a potential vote of censure. “Lord Randolph, however, persisted in his courses and, a few weeks later, in a letter to a Liberal-Unionist member, he repeated his menace in even clearer form.” Of the quoted passage in his father’s letter, Winston wrote “This jingling phrase, ‘Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right,’ was everywhere caught up. It became one of the war-cries of the time and spread with spirit-speed all over the country. The attitude of the Protestant North of Ireland became daily more formidable. The excitement in Belfast did not subside. Dangerous riots, increasing in fury until they almost amounted to warfare, occurred in the streets between the factions of Orange and Green… Lord Randolph was, of course, the object of severe attack from the Irish party and especially from Mr. Parnell, who accused him of inciting, unintentionally, to murder and outrage.”

Characteristically, Lord Randolph “declined to recede in any way from his words” and his own Conservative party “jeered him loudly when he said so.” Prime Minister Gladstone himself intervened in the debate, sternly proclaiming of Lord Randolph “If we were a weaker country with less solid institutions, such occurrences as this would, in my opinion, have called for severe and immediate notice.” Lord Randolph wrote to Prime Minister Gladstone to point out alleged inaccuracies in the words attributed to him. This caused Gladstone to reply to Lord Randolph tartly on 21 May 1886, directly quoting Lord Randolph’s 7 May letter: “…I am content to take your opinions as you have yourself expressed them in the closing paragraph of your letter to Mr Young. Let us, then, if you please, consider that paragraph as already substituted for my words.” Irish nationalists and their leader, Parnell, denounced Lord Randolph for inciting violence and fanning sectarian hatred.

… A victory…

Lord Randolph’s inflammatory rhetoric from this letter helped sweep the Tories to victory in the July 1886 General Election, unseating Gladstone and placing Lord Salisbury at the head of a Government in which Lord Randolph became both Leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

…and Defeat

But where Gladstone would return to the premiership (in 1892), Lord Randolph’s political career would be over by the end of 1886. Lord Randolph and Salisbury “shared a largely similar political ideology, but Salisbury lost patience with Churchill on a personal and tactical level.” When Lord Randolph submitted a posturing resignation on 20 December 1886 in protest over defence spending, Salisbury called his bluff and accepted. Lord Randolph was 37 years old. He would never hold Government office again, dying in January 1895 after the spectacular collapse of both his health and political career.

Aftermath and corrective echo

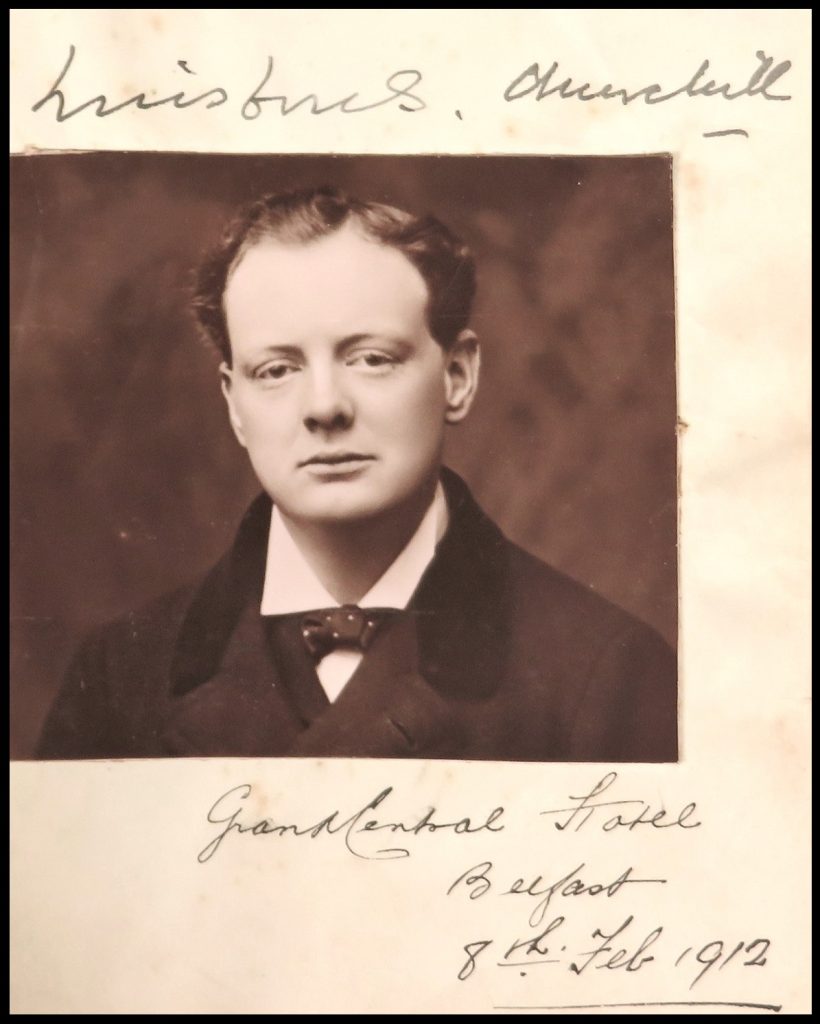

A quarter of a century after Lord Randolph Churchill wrote this letter – when his son, Winston, was the same age Randolph had been when he left the Government in 1886 – a strange, corrective echo occurred.

In the fall of 1911, Home Rule moved to the fore in political debate. Winston prepared to speak in the Ulster Hall in Belfast in favor of Home Rule – the very same hall where his father famously opposed Home Rule in 1886. “This was an anticipated, significant, and controversial event. Tensions were so high that the meeting was “transferred from the Ulster Hall which lay in the strongly Protestant area to a large marquee at the Celtic Road football ground in the Catholic working-class district.” History records that “Extraordinary precautions had to be taken to protect Churchill and his wife who had insisted on accompanying him. The Manchester Guardian reported that the railway line from Larne, where the Churchills landed in Ireland, to Belfast was patrolled by police to prevent sabotage.” The Churchills’ greeting was anything but friendly.

“A hostile crowd of nearly 10,000 greeted them outside the Grand Central Hotel in Belfast, where they were staying.” Of the drive from the hotel to Celtic Road, The Times reported “As each car made its way through, men thrust their heads in and uttered fearful menaces and imprecations.” The Manchester Guardian reported that “the back wheels of the Churchills’ car were lifted eighteen inches off the ground by the angry crowd before the police beat them off.” Churchill addressed a crowd of 5,000 Irish Nationalists, saying: “We look forward to a time… when the harsh and lamentable cry of reproach which so long jarred upon the concert of Empire will die away, when the accursed machinery, by which the hatred manufactured and preserved will be broken forever.” Remembering his experience in South Africa and in marked contrast to his father’s inflammatory rhetoric, Churchill said, “We have made friends with our enemies – can we not make friends with our comrades too?”

This was a dramatic generational turn – and a dramatic turn for Winston Churchill as well. The younger Churchill had inherited his initial views about Ireland from his father. On 6 April 1897, three and a half years before his first election to Parliament, the young Winston wrote to his mother “Were it not for Home Rule – to which I will never consent – I would enter Parliament as a Liberal.” In May 1904, Churchill broke with his father’s Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal.

It has been asserted that Winston’s experience during the Boer War – as a journalist, combatant, prisoner, and fugitive – gave him some sympathy for Irish concerns. Certainly, by the first time he ran as a Liberal, his father’s hard line against Home Rule had begun to soften in Winston. And it also seems plausible that his initial stints in Government, including as Undersecretary of State for the Colonies (1905-1908), further informed his perspective. By 1911, his position had reversed entirely.

The Home Rule crisis of 1912-1914 was sidelined by the outbreak of the First World War. But on 16 February 1922, as Britain’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Winston S. Churchill introduced the Irish Free State Bill, and pressed successfully for its swift passage, formally establishing the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth.

One might fairly point out that Churchill’s evolved, expansive view on Irish self-government contrasts sharply with, say, his views on Indian independence. But that is another topic for another post…

Cheers!

References: Gilbert, Vol. II; Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill; ODNB; Hillsdale College, The Churchill Project