“This is not journalism; it is falsification of History.

Winston has very obviously made history in two wars,

made mistakes, made successes, made history,

but as a writer of history he is unreliable, partisan & distortionist.”

Churchill’s first cousin, Captain Oswald M. Frewen,

excerpt from annotations to 1916-1918, Part I., page 157

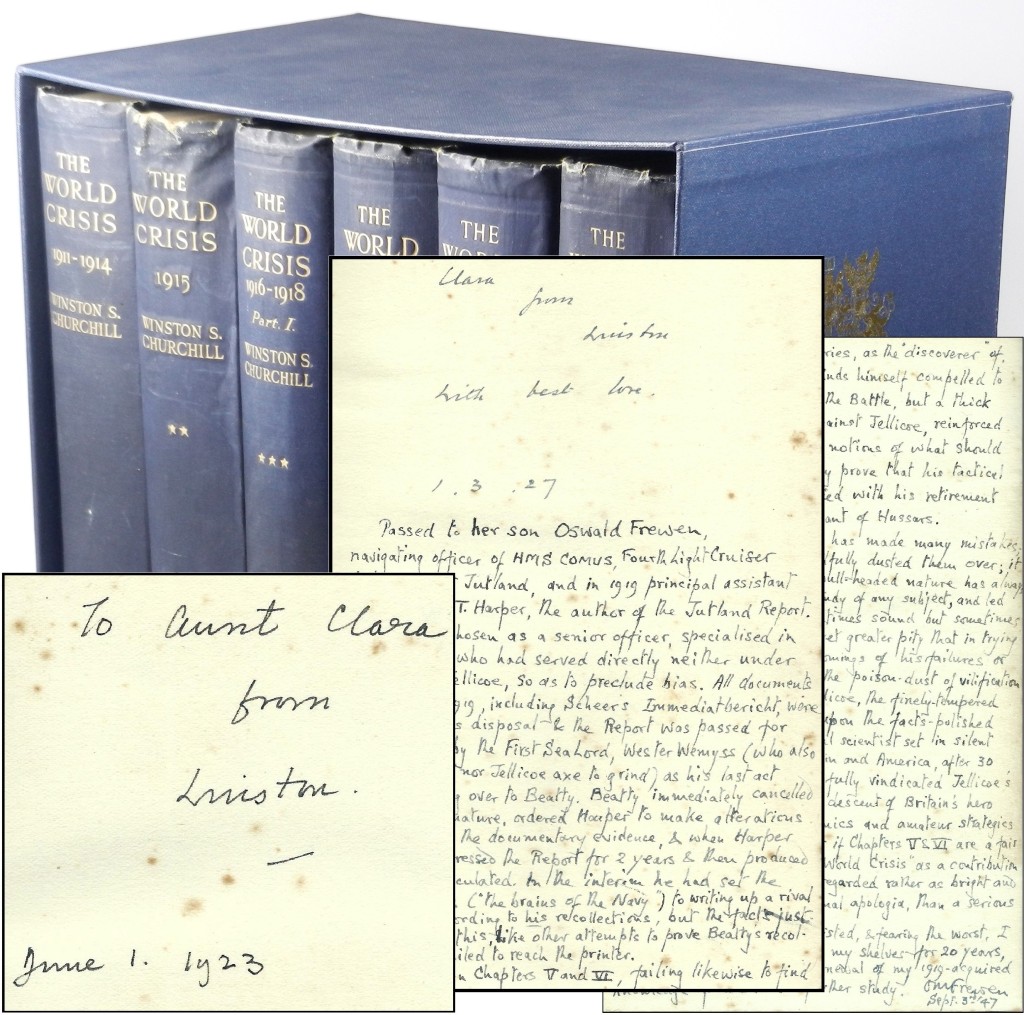

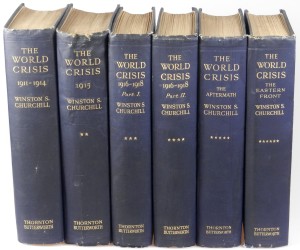

Churchill Book Collector is pleased to present an extraordinary set of The World Crisis, Churchill’s history of the First World War. Each of the five books (the 1916-1918 book was issued in two volumes) is inscribed in the year of publication by Churchill to his Aunt Clara. The books passed to Clara’s son and Churchill’s first cousin Captain Oswald Frewen, a career naval officer who served under Churchill’s leadership as First Lord of the Admiralty during both the First and Second World Wars. Of note to both collectors and scholars, Oswald added extensive, expert, and highly critical annotations to the set, focused on the Battle of Jutland and naval and civilian leadership.

This is our latest offering from the incredible Frewen family collection. To read more about the collection, please see our January 12th blog post.

Of course only one collector or institution will be able to purchase this set, but its singularity warrants sharing with a broader audience. Hence this lengthy post, which includes details about the inscriptions, the annotations, edition, and condition, as well as biographical sketches of Churchill’s Aunt Clara and Cousin Oswald.

The Volumes and Inscriptions

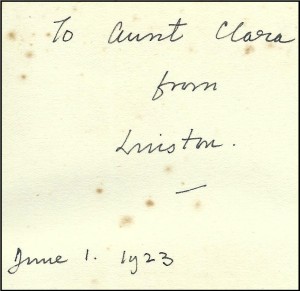

Volume I, 1911-1914

The first edition, second printing. The second printing was actually ordered before publication of the first printing (April 10, 1923) and printed only three days after publication of the first printing (on 13 April, 1923). The four-line inscription in black ink on the second free endpaper recto reads:

To Aunt Clara

from

Winston.

June 1. 1923

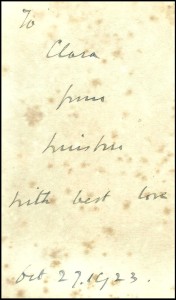

Volume II, 1915

The first edition, first printing, inscribed three days prior to publication (October 30, 1923). The five-line inscription in black ink on the second free endpaper recto reads:

To

Clara

from

Winston

With best love

Oct 27. 1923.

Volume III, 1916-1918, Part I.

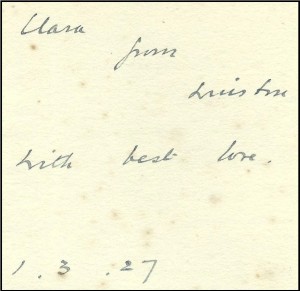

The first edition, first printing, inscribed two days prior to publication (March 3, 1927). The five-line inscription in black ink on the second free endpaper recto reads:

Clara

from

Winston

With best love.

1.3.27

Volume III, 1916-1918, Part II.

The first edition, first printing, not inscribed, as Parts I & II were published together as a single book in two volumes.

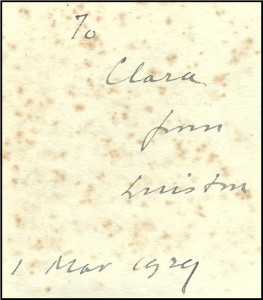

Volume IV, The Aftermath

The first edition, first printing, inscribed six days prior to publication (March 7, 1929). The five-line inscription in black ink on the second free endpaper recto reads:

To

Clara

from

Winston

1 Mar 1923

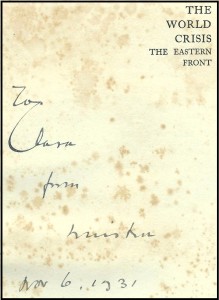

Volume V, The Eastern Front

The first edition, first printing, inscribed early in the month of publication (November 1931, specific day of publication unknown). The five-line inscription in black ink on the half-title recto reads:

To

Clara

from

Winston

Nov 6. 1931

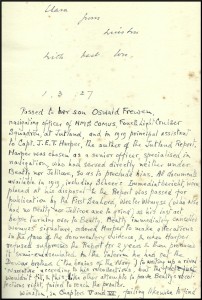

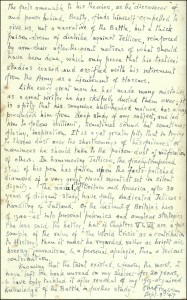

Captain Frewen’s Annotations

“Passed to her son Oswald Frewen, navigating officer of HMS COMUS, Fourth Light Cruiser Squadron, at Jutland, and in 1919 principal assistant to Capt. J. E. T. Harper, the author of the Jutland Report. Harper was chosen as a senior officer, specialised in navigation, who had served directly neither under Beatty nor Jellicoe, so as to preclude bias…. fearing the worst, I have left the book unread on my shelves for 20 years, & have only tackled it after renewal of my 1919-acquired knowledge of the Battle in further study.

OMFrewen

Sept. 3rd ’47”

This excerpt is taken from the incredible 500+ word prelude to Captain Oswald Frewen’s annotations that immediately follows the author’s inscription to his Aunt (and Oswald’s mother) in the first 1916-1918 volume.

Captain Frewen’s extensive annotations appear throughout the two 1916-1918 volumes and run to thousands of words. These annotations are remarkably informed and informative, sharply critical, and compellingly interesting.

Showing throughout all of his annotations is Captain Frewen’s clear and partisan admiration for Jellicoe and dismissive loathing of Beatty. At points, Captain Frewen’s critiques of Winston’s assertions echo the traditional derisiveness of one service branch for another (Frewen a career Naval officer, Churchill’s military career spent in the cavalry and then briefly as an infantry Lieutenant Colonel in the trenches during the First World War). One sample among many: “I am afraid, even from the calm cool armchair, obscured by nothing more than cigar smoke, Winston emerges as a very 8th rate Admiral whatever he may have been as Lieut. of Horse or Col. of Infantry.” Moreover, some of Oswald’s sarcasm and sniping can easily be attributed to the jealousy of a cousin toward the relentlessly eclipsing lodestar that was Winston Churchill.

Nonetheless, Oswald participated in every naval engagement in the North Sea during the First World War, after the war helped the Admiralty prepare the official history of Jutland, and during the Second World War he served as King’s Harbour Master of Scapa Flow. His annotations are, at points, remarkably specific and appear highly informed.

Oswald’s comments are not without some expressed admiration for his Cousin Winston’s gifts – both literary and as a leader. And tempering the sharp criticism is the knowledge that Oswald actively sought – and received – his Cousin’s Winston’s inscriptions in books that Oswald read and annotated until Oswald’s death in 1958. The Frewen collection includes the entire six-volume history, The Second World War, (published between 1948 and 1954) inscribed to Oswald with his suggested edits, as well as volumes of Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (published between 1956 and 1958) inscribed to Oswald.

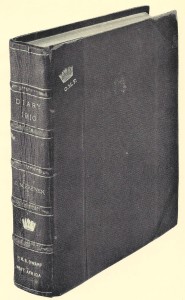

A final consideration is the fact that, according to the Frewen family, Oswald’s own 1916 diary “is considered to be part of the United Kingdom’s national archives because of his description of the Battle of Jutland,” with a claim upon the volume made by the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth, England.

In sum, it would seem inappropriate to dismiss Captain Frewen’s annotations as simply partisan or jealous. They make this set not just a prized association copy, but also a relevant and unique piece of history.

In recognition of that significance, we have transcribed the entirety of Captain Frewen’s annotations. The verbatim transcription, location description, and context of each comment within the text runs to 22 typed pages. We will provide this transcription upon request to interested parties, including scholars and prospective buyers.

The Associations

We include biographic sketches of both Churchill’s Aunt Clara, to whom the volumes were originally inscribed, and her son, Churchill’s first cousin Oswald, who inherited and annotated the set.

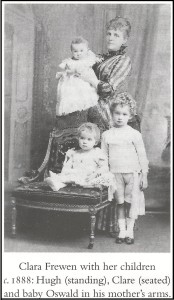

Clarita Jerome Frewen

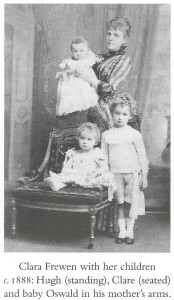

Clarita “Clara” Jerome Frewen (1851-1935) was the eldest of the three famous Jerome sisters. Middle sister Jeanette “Jennie” Jerome (1854-1921) became Lady Randolph Churchill and mother to Winston Churchill. Youngest sister Leonie Blanche Jerome (1859-1943) became Lady Leslie, wife of Sir John “Jack” Leslie, an Anglo-Irish baronet.

Clarita “Clara” Jerome Frewen (1851-1935) was the eldest of the three famous Jerome sisters. Middle sister Jeanette “Jennie” Jerome (1854-1921) became Lady Randolph Churchill and mother to Winston Churchill. Youngest sister Leonie Blanche Jerome (1859-1943) became Lady Leslie, wife of Sir John “Jack” Leslie, an Anglo-Irish baronet.

Clara’s father, Leonard Jerome (1817-1891), was a wealthy New York stock speculator, sportsman, and patron of the arts. Clara’s mother, Clarissa Hall, was an orphaned heiress who in the 1860s quitted New York to take her daughters to Paris, where they spent formative years at the court of Napoleon III. Blond, blue-eyed Clara made her debut before the Franco-Prussian war sent the Jerome women to England. There Jennie and Clara caused sensation, wearing matching gowns to society parties, playing after-supper piano duets, and acquiring a reputation for wit and beauty.

Jennie’s marriage in 1873 to the son of the Duke of Marlborough both produced Winston Churchill and introduced sisters Clara and Leonie to aristocratic England, from which their own marriages would ensue.

In 1881, Clara, described as “dreamy” and “fey,” married Moreton Frewen (1853-1924), “a dashing, handsome sportsman from a distinguished Sussex family” and “a younger son with no money” who “tried relentlessly but unsuccessfully to translate his good looks and riding prowess into a fortune.” (Kehoe, Fortune’s Daughters, p. xxi) Moreton was undeniably brave, magnetic, and even visionary, but expensive tastes and wild schemes were his undoing; he would amass a lifetime of financial failures, earning the family nickname “Mortal Ruin.”

It was Uncle Moreton who famously edited Winston Churchill’s first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, with the same diligence and good fortune he applied to his finances. The result was a profusion of spelling and detail errors that incensed his nephew and resulted in later states of the work bearing lengthy errata slips.

Three children were born to Clara and Moreton – Hugh (1883-1967), Clare (1885-1970), and Oswald (1887-1958).

Three children were born to Clara and Moreton – Hugh (1883-1967), Clare (1885-1970), and Oswald (1887-1958).

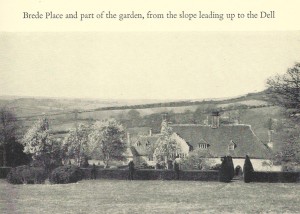

Despite a “fluttery appearance” and penchant for living a lifestyle her means could never support, Clara “could display a mule-like determination” and seemed to genuinely love her husband. Clara found a form of peace at Brede Place, her and Moreton’s home in East Sussex, which they managed, barely, to keep afloat, partly via loans exacted by Moreton from their children.

It is a measure of Clara’s odd social grit and the financial charade of her and Moreton’s life that when bailiffs came to Brede Place in 1908 she paid one of them “ten shillings to answer the door and polish the mirrors.” (Kehoe, Fortune’s Daughters, p.255) In that year, Clara saw her personal possessions auctioned to pay creditors, and it was only the largesse of family and friends that saw some purchased and returned to her.

After a lengthy illness and infirmity, Moreton died in 1924. Clara would remain at Brede Place – despite the terrible financial pressures it imposed on her and her family – until an August 1933 heart attack forced her into a nursing home, where she died on 20 January 1935.

Upon her death, the notice in the Peterborough column of the Daily Telegraph said of Clara: “Mrs. Frewen never took quite the same prominent place in society as her more brilliant sisters. She was, however, a well-known figure in the political and social circles of her time.”

Her nephew, Winston, was “ever considerate to his aunt.” At his mother’s funeral, even in distress Churchill showed kindness to Clara; he “sought her out in the train, made sure that she was given precedence on arrival, and later took the time to show her round the gardens at Blenheim.” In May 1930, Churchill came to tea at Brede Place and “to Clara’s delight, planted a tree in her ‘celebrity’ tree grove.” (Kehoe, Fortune’s Daughters, p.354-5)

The day before she died, Clara wrote to Churchill: “Darling Winston, I want to tell you I did so love your dear letter and know it was your own hand – & know it was your very own right hand that touched that paper. My old heart goes out to you. I have loved you ever since you were a baby and my blessing and peace be upon your darling head.” (Gilbert, Companion Volume V, Part 2, p.1035-6) Churchill wrote to his wife on 23 January 1935: “Poor old Clara died at 82 last Friday. Advised in time by Oswald, I wrote her a letter of affection which reached her on her last day… She was a vy good woman, who had much unhappiness; she was devoted to my Mamma & hence to me.” (Gilbert, Companion Volume V, Part 2, p.1042)

Winston Churchill dutifully inscribed first edition copies of his books to Clara over the course of three decades, from his earliest works into the 1930s, just prior to her death.

Captain Oswald Moreton Frewen

Oswald Moreton Frewen (1887-1958) was first cousin to Winston Churchill (1874-1965). His mother Clara (1851-1935) was the eldest sister of Churchill’s mother, Jennie (1854-1921). Oswald was the youngest of three children born to Clara Jerome Frewen and Moreton Frewen.

Oswald shared many attributes with his famous cousin – among them a vigorous individualism, a deep-seated contrariness, humor and charm, a sense of adventure, courage, and a great facility for words. Where he differed was in either a dislike or discomfort with society, “excusing his reluctance with a kindly contempt for its vanities.”

These similarities and differences play out in the relative trajectories of Oswald and Winston. Winston began as a military officer and war correspondent, which he parlayed into historic careers in politics and as an acclaimed author. Oswald was “a naval officer first and a barrister second, and by inclination an independently minded square peg who moved with great charm and courage from one round hole to the next…” Oswald “employed his own considerable talents with the pen principally by writing a diary” which ran to a remarkable 55 volumes over the course of his life. (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Preface by G.P. Griggs, p.9) In fact, Oswald’s obituary in The Times described him as “the most indefatigable diarist of his generation.”

These similarities and differences play out in the relative trajectories of Oswald and Winston. Winston began as a military officer and war correspondent, which he parlayed into historic careers in politics and as an acclaimed author. Oswald was “a naval officer first and a barrister second, and by inclination an independently minded square peg who moved with great charm and courage from one round hole to the next…” Oswald “employed his own considerable talents with the pen principally by writing a diary” which ran to a remarkable 55 volumes over the course of his life. (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Preface by G.P. Griggs, p.9) In fact, Oswald’s obituary in The Times described him as “the most indefatigable diarist of his generation.”

Oswald himself observed the “streak of pertinacity and persuasiveness in the Jeromes which at crisis accomplishes much” and noted that this streak “became apparent to the world… in… Winston.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, p.18) Oswald and Churchill may have shared a “disregard for any conventional method of going about things” but where Churchill met disappointment and opposition with willful defiance, Oswald was less compelled to impose his own will and more inclined to “look at the funny side of things and laugh at a world which won’t always laugh with me.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, p.14)

This pervasive perspective of the outsider is echoed in Oswald’s own comments about his famous cousin: “One of my earliest recollections is of a visit to Banstead manor near Newmarket which my Aunt Jennie had taken. She invited us three children to go and stay with her two, Winston and Jack. My brother Hugh, three years older than I, palled up with the Churchills, and these three elders herded apart and referred to my sister Clare and me, slightly and condescendingly, as ‘the little ones’. In my infant eyes Winston’s dozen years’ excess of life over mine made him seem avuncular rather than cousinly, a kind of early hall-mark which I have never been able to eradicate.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, p.13)

Oswald attended Eton and then joined the Royal Navy in 1902, his “first and only love in the realm of vocation.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Concluding Note by Leigh Holman, p.246) Oswald would be present in every naval engagement in the North Sea during the First World War and, after the war, serve for a period at the Admiralty assisting preparation of the official naval history of the war. Nonetheless, Oswald’s naval career was perhaps limited by “an instinctive mistrust of all those in authority in the Service, Lords Charles Beresford and Jellicoe excepted.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Concluding Note by Leigh Holman, p.246)

Oswald left the Navy as a Commander in 1922 to pursue careers variously in the law and journalism. When Oswald decided to apply for the Bar, Winston was asked to provide a character reference. “Oswald had left a section of his reference form blank and, to his delight, Winston added the statement: ‘He is my first cousin & I have been in close touch with him continuously. He was a good officer in the Royal Navy and present at several actions, writes well, & has shewn himself a good & devoted son.’ (Fortune’s Daughters, Elisabeth Kehoe, p.347)

Nonetheless, the law was a bust for Oswald. Consistent with his streak of restless Frewen contrarianism, the law’s “daily grind of doing long and boring pleadings for his Master… had no charms for him.” His close friend Leigh Holman later wrote of Oswald: “His four years at the Bar were lean indeed for him, but a glorious light relief to the rest of us in the Chambers who were trying to work but always willing to be entertained.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Concluding Note by Leigh Holman, p.246)

Journalism perhaps suited Oswald’s adventurous side and his interest in “the failings and shortcomings of all those in authority, particularly if they were public concerns.” (Sailor’s Soliloquy, Concluding Note by Leigh Holman, p.245) Perhaps most notably, Oswald was able to combine his sense of adventure, his love of motorbikes, and his close bond with his turbulently flamboyant sister Clare, during a 1924 trip across Europe to Russia, with Clare in his sidecar. Nonetheless, adventure did not translate to a reliable career. Oswald “managed to generate some income through his writing, but it was insufficient to run the household.” (Fortune’s Daughters, Elisabeth Kehoe, p.352)

Oswald would notably return to active service in 1939. The same year that Winston returned to the Government as First Lord of the Admiralty, Oswald returned to the Navy as King’s Harbour Master of Scapa flow, a post he held from March 1939 to September 1942, also playing a role in the Algiers and Normandy landings and finally retiring from the Navy in 1945 with the rank of Captain.

That same year, Oswald married Lena Marson Spilman (1902-1988). They would spend the rest of Oswald’s life at his beloved home, “The Sheephouse” in Brede, East Sussex, an old sheep barn on 100 acres that he purchased in 1928 and converted into an Elizabethan half-timbered cottage. (It was in this house as Oswald’s guest that Laurence Olivier proposed to Vivian Leigh, who, along with her previous husband, was a friend of Oswald.) Oswald died in 1958.

That same year, Oswald married Lena Marson Spilman (1902-1988). They would spend the rest of Oswald’s life at his beloved home, “The Sheephouse” in Brede, East Sussex, an old sheep barn on 100 acres that he purchased in 1928 and converted into an Elizabethan half-timbered cottage. (It was in this house as Oswald’s guest that Laurence Olivier proposed to Vivian Leigh, who, along with her previous husband, was a friend of Oswald.) Oswald died in 1958.

The Edition

The World Crisis is Churchill’s history of the First World War, originally published in six volumes between 1923 and 1931.

The first four volumes comprise the history of the war years 1911-1918 and were published between 1923 and 1927. Two supplemental volumes followed in 1929 and 1931. These were The Aftermath, covering the years 1918-1928, and The Eastern Front, which Churchill initially proposed as “separate from but supplementary to our five volume history”, intended to describe in greater detail “the course of events in the Eastern theatre” (Cohen, Vol. I, p.234).

Of The World Crisis, Frederick Woods wrote, “The volumes contain some of Churchill’s finest writing, weaving the many threads together with majestic ease, describing the massive battles in terms which fitly combine relish of the literary challenge with an awareness of the sombre tragedy of the events.” Churchill was in a special position to write this history, having served both in the Cabinet and on the Front.

Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1911 until 1915, but after the failure in the Dardanelles and the slaughter at Gallipoli, he was scapegoated by his peers, betrayed by his Prime Minister, and hounded by the Conservatives. Churchill would go from the Cabinet to the Front, serving as a lieutenant colonel leading a battalion in the trenches.

By the war’s end, Churchill was exonerated by the Dardanelles Commission and rejoined the Government, but the stigma of the Dardanelles would linger. Churchill wrote his history of the First World War in part to clear his name and reputation, but the six volume masterwork he produced far exceeds this purpose.

The U.S. is the true first edition, as U.S. publication of Volume I (6 April 1923) preceded the British (10 April 1923). Nonetheless, the British first edition is prized. The British first edition was more uniform in appearance, with identical dark blue cloth bindings. Many consider the British edition aesthetically superior to the U.S., with its larger volumes and shoulder notes summarizing the subject of each page. There were multiple printings of each volume of the British first edition, with various small differences to bindings, content, and dust jackets.

Condition

“I am one of those horrible readers who deface their books with marginal comments…”

Oswald wrote these words on February 17, 1953, on the first free endpaper of his copy of Winston’s fifth Volume of The Second World War. Oswald addressed his comments to Jock Colville, Churchill’s Private Secretary, to whom he was sending the book both with suggested edits and in order to receive it back with his cousin Winston’s signature. Winston obliged.

This comment from Oswald aptly indicates the condition of this remarkable set of The World Crisis he inherited from his mother, and subsequently read and heavily annotated.

This set is in sound, original, unrestored condition, with the original bindings all firm and intact, but is certainly well short of fine and is obviously to be prized far more for provenance and content than for condition.

This set is in sound, original, unrestored condition, with the original bindings all firm and intact, but is certainly well short of fine and is obviously to be prized far more for provenance and content than for condition.

Five of the six volumes are first edition, first printing (most having been inscribed by the author to his Aunt Clara prior to publication. Volume I, the 1911-1914 volume, is first edition, second printing. As noted above, the second printing of Volume I was actually ordered before publication of the first printing (April 10, 1923) and printed only three days after publication of the first printing (on 13 April, 1923).

The blue cloth bindings are all square and tight, but show some of the scuffing endemic to the smooth navy cloth and slight wear to extremities. Additionally, we note the following: very slight outward warping to the 1915 volume boards; a pull and some minor fraying at the head of the 1915 volume spine; minor blistering of The Aftermath cloth (to which this particular volume was prone) on the upper front cover and lower right of the spine; some minor discoloration spots to The Eastern Front front cover and a wrinkle (binding error rather than blistering) in the upper rear cover cloth.

The contents of all six volumes show the spotting to which this edition proved vulnerable. Spotting is substantially confined to the page edges and first and final leaves, the heaviest instance within the set observed on the inscribed page of the 1915 volume. We note no previous ownership marks beyond the author’s inscriptions and Captain Frewen’s annotations.

The contents of all six volumes show the spotting to which this edition proved vulnerable. Spotting is substantially confined to the page edges and first and final leaves, the heaviest instance within the set observed on the inscribed page of the 1915 volume. We note no previous ownership marks beyond the author’s inscriptions and Captain Frewen’s annotations.

The set is housed in a navy cloth slipcase with gilt print and decoration on the right side.

Bibliographic reference: Cohen A69.2(I).d, A69.2(II).a, A69.2(III-1).a, A69.2(III-2).a, A69.2(IV).a, A69.2(V).a.; Woods/ICS A31(ab), Langworth p.105

Bibliographic reference: Cohen A69.2(I).d, A69.2(II).a, A69.2(III-1).a, A69.2(III-2).a, A69.2(IV).a, A69.2(V).a.; Woods/ICS A31(ab), Langworth p.105

Terms and Additional Information

Please inquire with us about availability and terms, or for a full transcription and additional information about the remarkable annotations.

Cheers!

Churchill Book Collector