We recently discovered a wonderful first edition inscribed during Churchill’s first lecture tour of the United States and Canada. This book has never been offered for sale and was unknown to the collecting community.

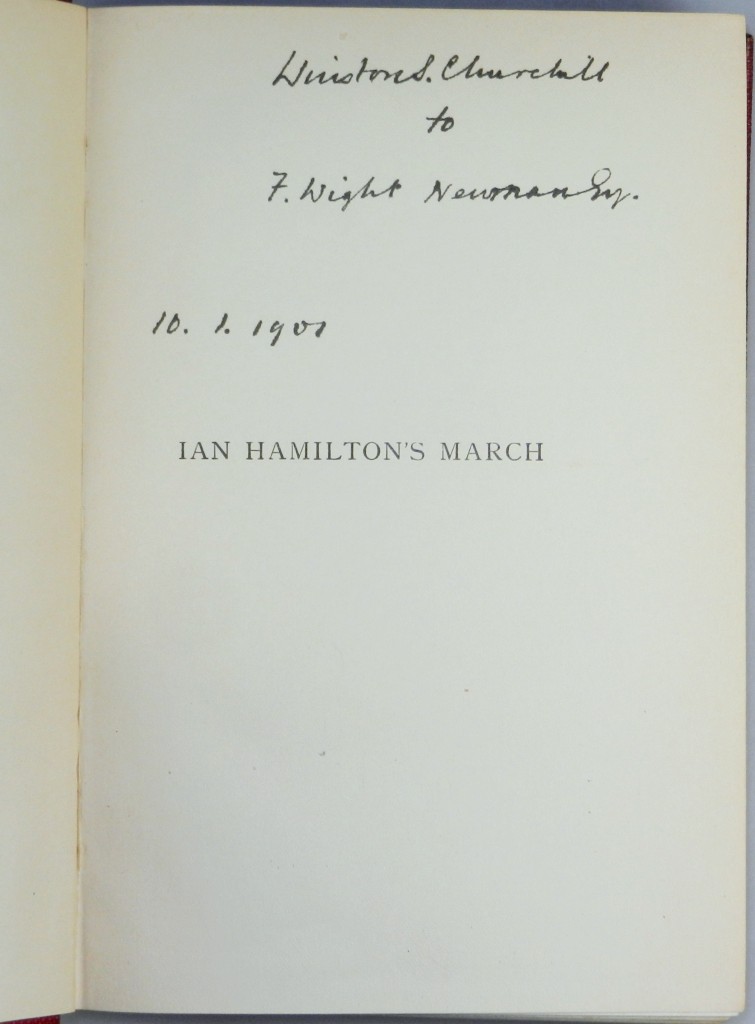

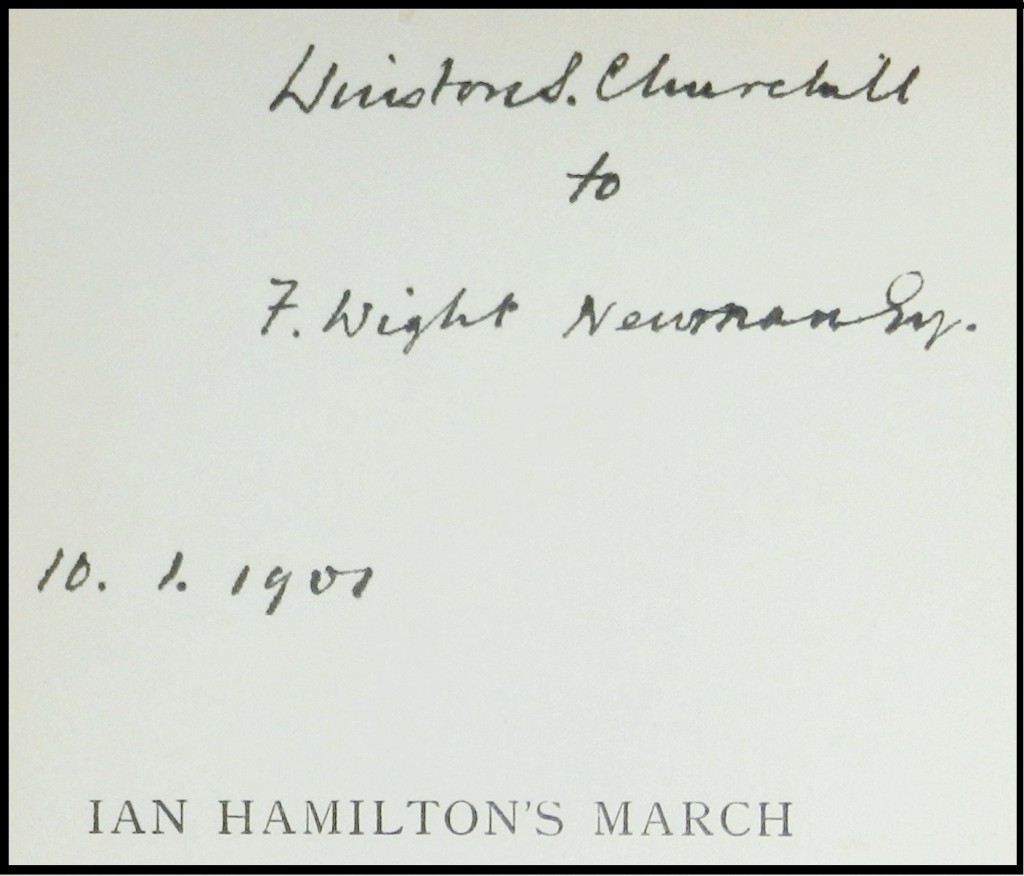

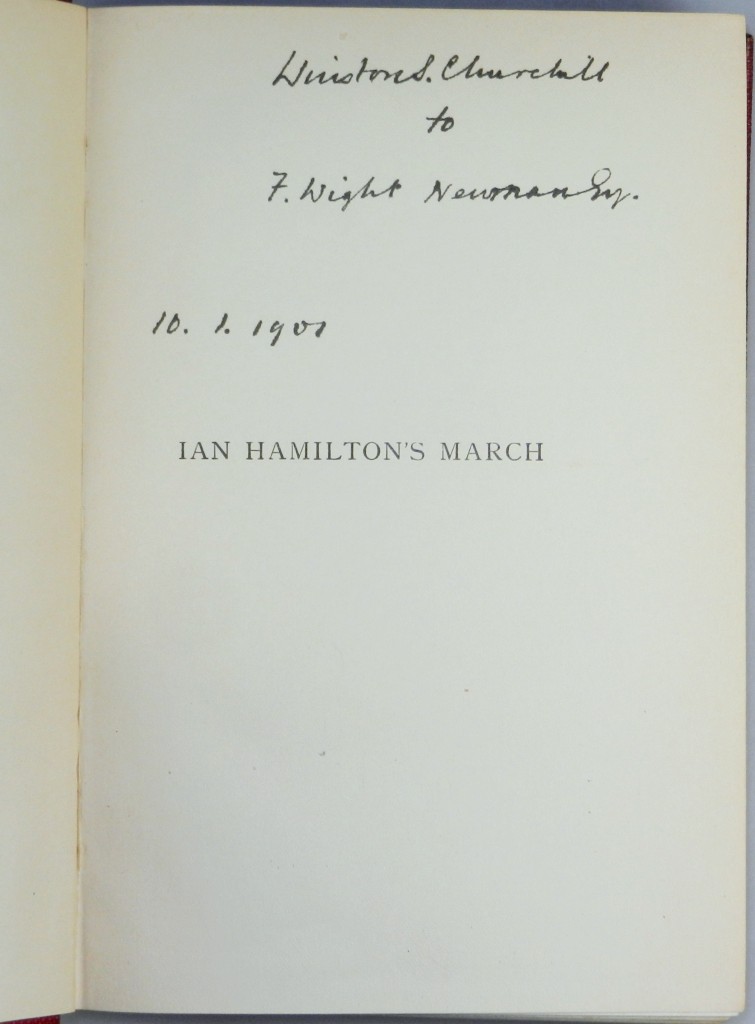

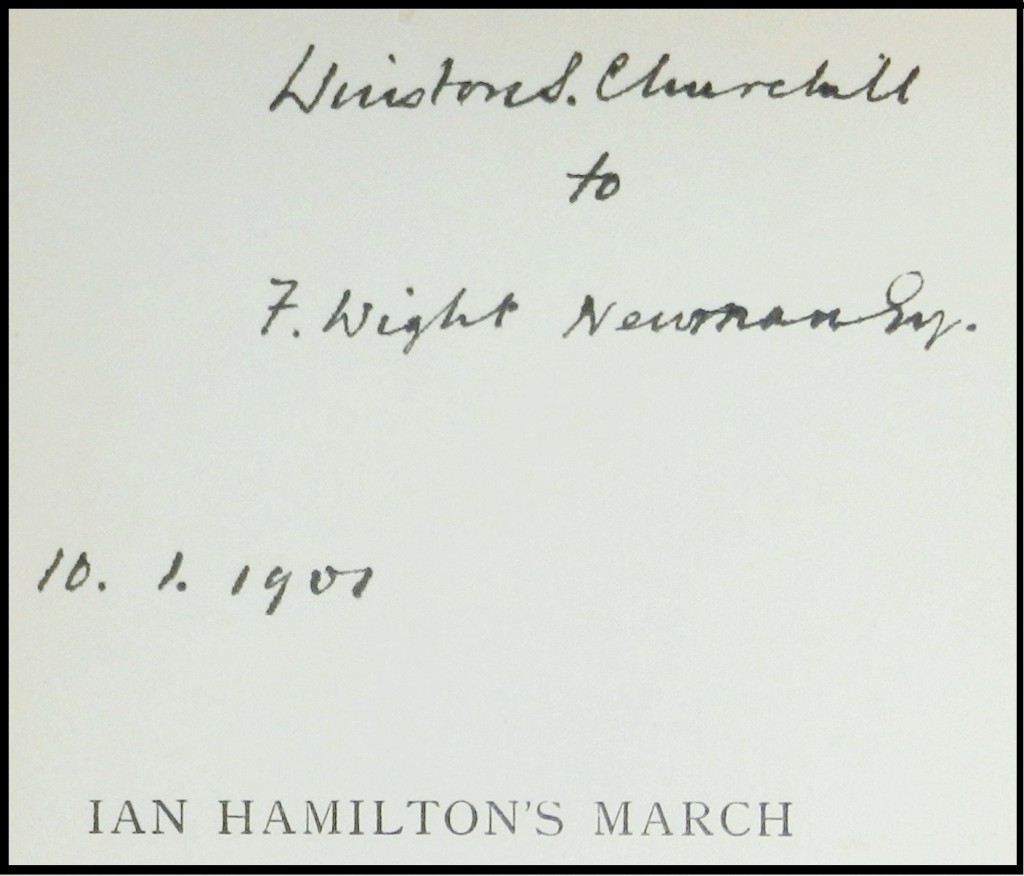

This is the U.S. first edition of Churchill’s fifth book, inscribed by Churchill for noted impresario F. Wight Neumann in Chicago on 10 January 1901. The signature, in black ink in four lines on the upper half-title, reads: “Winston S. Churchill | to | F. Wight Neuman Esq. | 10.1.1901”

Provenance

Unlike so many signed copies, we have provenance going back to the time of signing. The book remained in Neumann’s family for more than a century, until 2003, when ownership transferred from Neumann’s grandson, Sterling E. Selz, to his friend and fellow collector John Patrick Ford, from whom it was acquired by Churchill Book Collector.

In 1900, Churchill had won his first seat in Parliament partly on the strength of his celebrity as a Boer War hero, having been captured and made a daring escape. Churchill’s lecture tour of the United States and Canada was intended to improve his finances at a time when MPs received no salary. Churchill arrived in New York on board the Lucania on December 8, 1900.

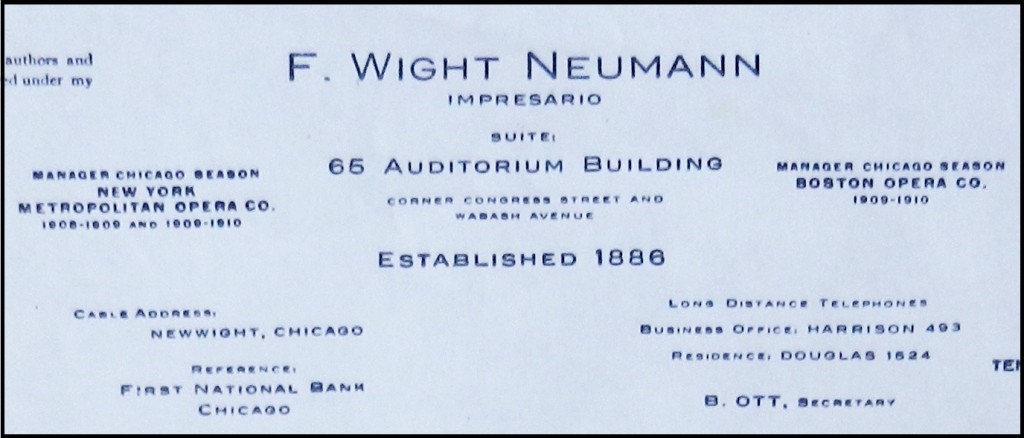

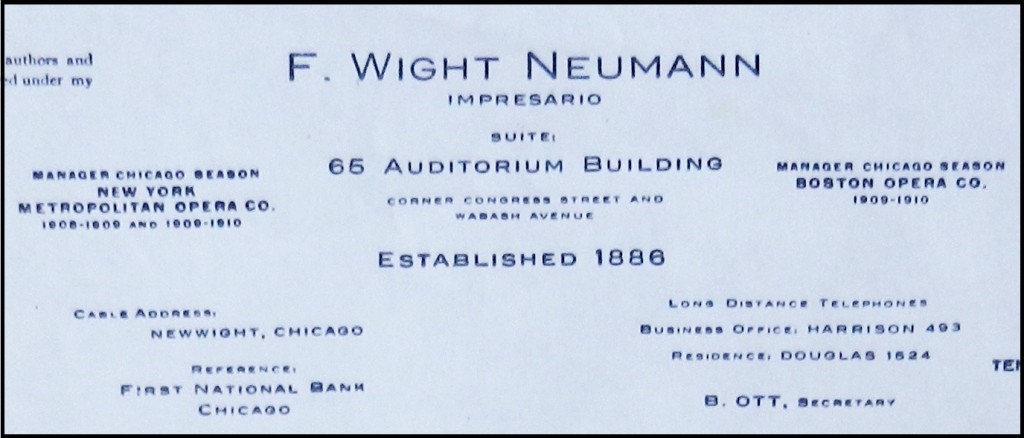

German-born F. Wight Neumann (1851-1924) was a Chicago-based impresario, “one of the most noted impresarios in America” and “friend of virtually every prominent musician in the country” who “brought all of the great artists of the world to Chicago.” (Chicago Daily Tribune, 23 October 1924 Obituary) Neumann emigrated to America in 1877, originally training for a banking career. He came to Chicago in 1884.

Circa 1923, the photo shows, from left to right, F. Wight Neumann, Mrs. Neumann, Sterling Selz, Gladys Selz, and Austin Sell

In addition to an incredible stable of musicians, vocalists, opera companies, orchestras, and conductors, also appearing under Neumann’s management in Chicago were select authors and lecturers, among them the young Winston Churchill.

Arriving in Chicago on the morning of 10 January 1901, Churchill lectured that evening on “The Boer War as I Saw It” at Central Music Hall and was entertained after his lecture by “forty members of the University Club at an informal reception in the club grillroom.”

Churchill’s lecture tour had faced challenges and disappointments, among them smaller audiences and profits than anticipated, a frustrating tour manager, and the “strong pro Boer feeling” among “almost half” of some of his audiences. (21 December 1900 letter from Churchill to his mother) By the time of his Chicago lecture, Churchill had apparently found ways to deal with this last problem. When he displayed an image of “a typical Boer soldier” a gallery spectator hurrahed the Boers and “the cry was taken up by a large part of the audience,” followed by hisses from pro-British listeners.

Churchill deftly responded: “Don’t hiss. There is one of the heroes of history. The man in the gallery is right. No true-hearted Englishman will grudge a brave foe cheers.” This “put the audience in good humour” and gave Churchill “the considerate attention of his audience.” (The Chicago Tribune, 11 January 1901) Churchill’s lecture “was much interrupted with the applause of an audience which comfortably filled the hall.” At his reception following the lecture, “Mr. Churchill was called on for a speech and replied in a witty recital of the many bonds of union which exist between the English and Americas.” (The Chicago Tribune, 11 January 1901)

Churchill left the United States for England on 2 January aboard the SS Etruria. In a lecture tour that had proven both challenging and exhausting, Churchill had met President McKinley, dined with recently elected Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt, and been introduced by Mark Twain. He had taken his first full measure of the tenor and spirit of the nation that would prove his – and Britain’s – vital partner in the two world wars to come. While Churchill was abroad, Queen Victoria died, and the end of her 64-year reign also closed Churchill’s Victorian career as a cavalry officer and war correspondent adventurer. Churchill took his first seat in Parliament on 14 February 1901 and began a 60-year career as one of the 20th Century’s great statesmen.

The Edition

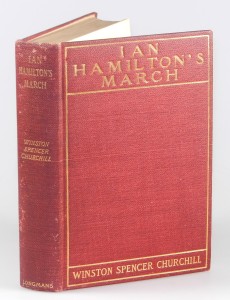

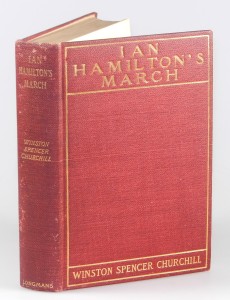

Ian Hamilton’s March is Churchill’s fifth public book and the second of Churchill’s two books based on his dispatches sent from the front in South Africa.

In October 1899, the second Boer War erupted in South Africa between the descendants of Dutch settlers and the British. As an adventure-seeking young cavalry officer and war correspondent, Churchill swiftly found himself in South Africa with the 21st Lancers and an assignment as press correspondent to the Morning Post. Not long thereafter – on 18 November 1899, Churchill was captured during a Boer ambush of an armored train. His daring escape less than a month later made him a celebrity and helped launch his political career.

Churchill’s first Boer War book, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, contained 27 letters and telegrams to the Morning Post written between 26 October 1899 and 10 March 1900 and was published in England in mid-May. Ian Hamilton’s March completes Churchill’s coverage of the Boer War, comprising 17 letters to the Morning Post, spanning 31 March through 14 June 1900.

While London to Ladysmith via Pretoria had swiftly published Churchill’s dispatches in the wake of his capture and escape, for Ian Hamilton’s March “the texts of the originally published letters were more extensively revised and four letters were included which had never appeared in periodical form” (Cohen, A8.1.a, Vol. I, p.105). Churchill effected these revisions while on board the passenger and cargo steamer Dunottar Castle which was requisitioned as a troop ship, en route home to England.

Churchill arrived on 20 July 1900 and spent the summer campaigning hard in Oldham, capitalizing on his war status and winning his first seat in Parliament on 1 October 1900 in the so-called “khaki election.”

The narrative in Ian Hamilton’s March includes the liberation of the Pretoria prison camp where Churchill had been held and from which he had famously escaped. The title takes its name from General Sir Ian Hamilton’s campaign from Bloemfontein to Johannesburg and Pretoria. Churchill would maintain a life-long friendship with Hamilton, who would be involved in the Gallipoli landings and to whom Churchill would sell his first country home.

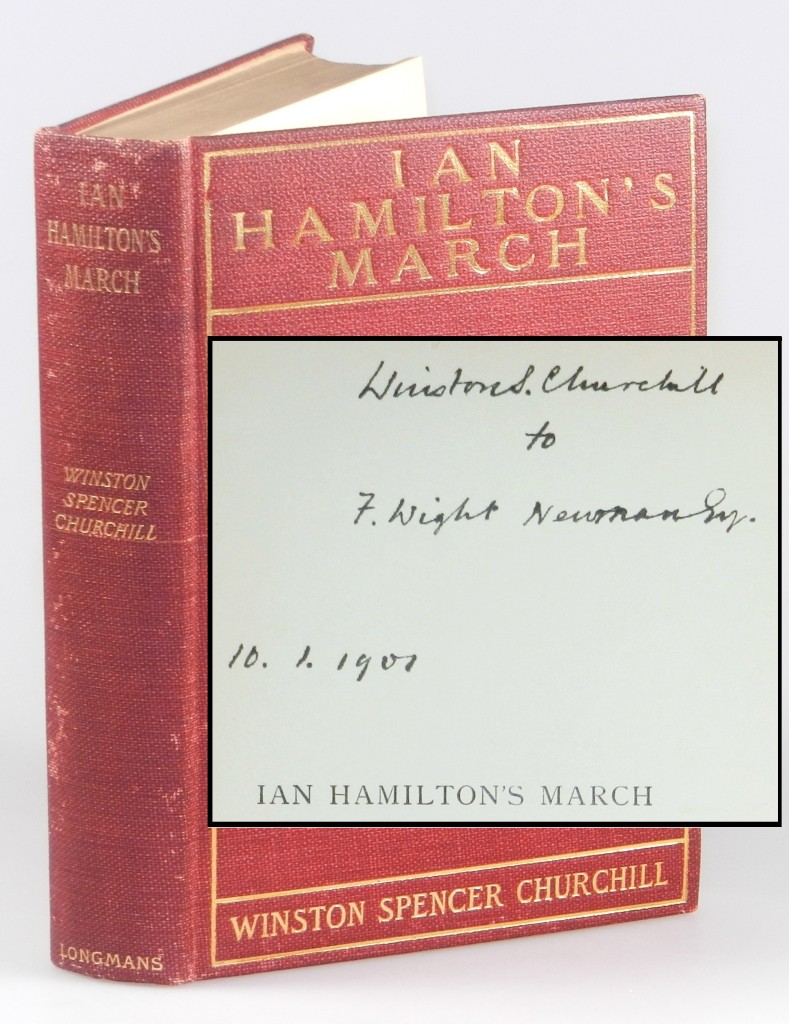

The U.S. first edition saw only a single printing. The number sold is unclear, but seems to be fewer than 1,500. Published on 26 November 1900, the U.S. first edition was thus available for sale when Churchill arrived in New York on 8 December 1900 for his first North American lecture tour.

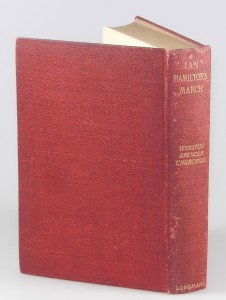

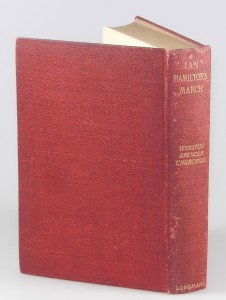

Like the U.S. first edition of Ladysmith, the U.S. first edition of Ian Hamilton’s March is bound in pebble grain red buckram which proved durable yet susceptible to blotchy wear and discolouration, particularly on the spine.

Condition

The excellent condition of this copy would make it collector-worthy, independent of the author’s signature.

The excellent condition of this copy would make it collector-worthy, independent of the author’s signature.

The red cloth binding remains unusually clean and tight, with sharp corners, and bright gilt and only trivial wear to extremities. The spine toning and uneven coloration endemic to this edition is mild. The spine retains excellent color and vivid gilt, with only a barely discernible hint of uniform toning and modest instances of the typical discoloration.

The contents remain uncommonly bright and crisp. A trace of spotting is confined to the frontispiece tissue guard and the fore edge. The top edge gilt remains bright. Other than the author’s inscription, the sole previous ownership marks we find are a half dozen illegible, tiny pencil script letters at the upper left rear pastedown that we have refrained from erasing just in case some future owner may be able to decipher them.

The inscription remains clear and bright, with minimal age spreading on a bright and otherwise unmarked half title page. The date is written with European, rather than U.S. precedence, with the month “1” following the day “10” making the date of inscription 10 January 1901. It is interesting to note that Churchill omits the second “n” at the end of Neumann’s name and it appears as if he initially misspelled the name as “Newman, with a bit of extra ink at the “um” transition seeming a possible attempt to correct the spelling error as it was being inked.