Tickets are, by nature, ephemeral things. Nonetheless, they can hold special and enduring significance, viscerally anchoring us to a place and time and reminding us of something special.

One such place and time worth remembering occurred just over 70 years ago in Fulton, Missouri, when Winston Churchill gave a famous speech at Westminster College.

We were very pleased recently to offer an original ticket and letter of invitation to this speech, and more pleased still at where it ended up, strengthening the common cause about which Churchill spoke that day, and which was a central feature in his long life. This blog post tells the story.

Churchill’s delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech on Tuesday, March 5, 1946, coining the phrase that described the division between the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence and the West. This speech incisively framed the Cold War that would dominate the second half of the Twentieth Century: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent…. I repulse the idea that a new war is inevitable; still more that it is imminent… If we adhere faithfully to the Charter of the United Nations and walk forward in sedate and sober strength seeking no one’s land or treasure, seeking to lay no arbitrary control upon the thoughts of men… the high-roads of the future will be clear, not only for us but for all, not only for our time, but for a century to come.”

Then-President Harry S. Truman traveled with Churchill by special train from Washington D.C. for the twenty four hour overnight journey to Jefferson City, Missouri specifically to introduce Churchill in Fulton. With them was Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy. During the journey, the three men discussed recent Soviet provocations in northern Persia and Turkey. “During the morning of March 5, as the train continued westward along the Missouri river, Churchill completed his speech for Fulton. It was then mimeographed on the train, and a copy shown to Truman” who told Churchill that he “thought it was admirable” and “would do nothing but good, though it would make a stir.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, pp.196-197).

Then-President Harry S. Truman traveled with Churchill by special train from Washington D.C. for the twenty four hour overnight journey to Jefferson City, Missouri specifically to introduce Churchill in Fulton. With them was Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy. During the journey, the three men discussed recent Soviet provocations in northern Persia and Turkey. “During the morning of March 5, as the train continued westward along the Missouri river, Churchill completed his speech for Fulton. It was then mimeographed on the train, and a copy shown to Truman” who told Churchill that he “thought it was admirable” and “would do nothing but good, though it would make a stir.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, pp.196-197).

Upon arriving in Jefferson City shortly before noon on March 5, Churchill, Truman, and Leahy drove to Fulton, where they met and lunched with Dr. Franc L. McCluer, the College president, before the academic procession and delivery of the speech. Though the subject of the speech was of utmost gravity, Churchill began with characteristic wit: “The name ‘Westminster’ is somehow familiar to me. I seem to have heard of it before.” The speech was broadcast throughout the United States.

Upon arriving in Jefferson City shortly before noon on March 5, Churchill, Truman, and Leahy drove to Fulton, where they met and lunched with Dr. Franc L. McCluer, the College president, before the academic procession and delivery of the speech. Though the subject of the speech was of utmost gravity, Churchill began with characteristic wit: “The name ‘Westminster’ is somehow familiar to me. I seem to have heard of it before.” The speech was broadcast throughout the United States.

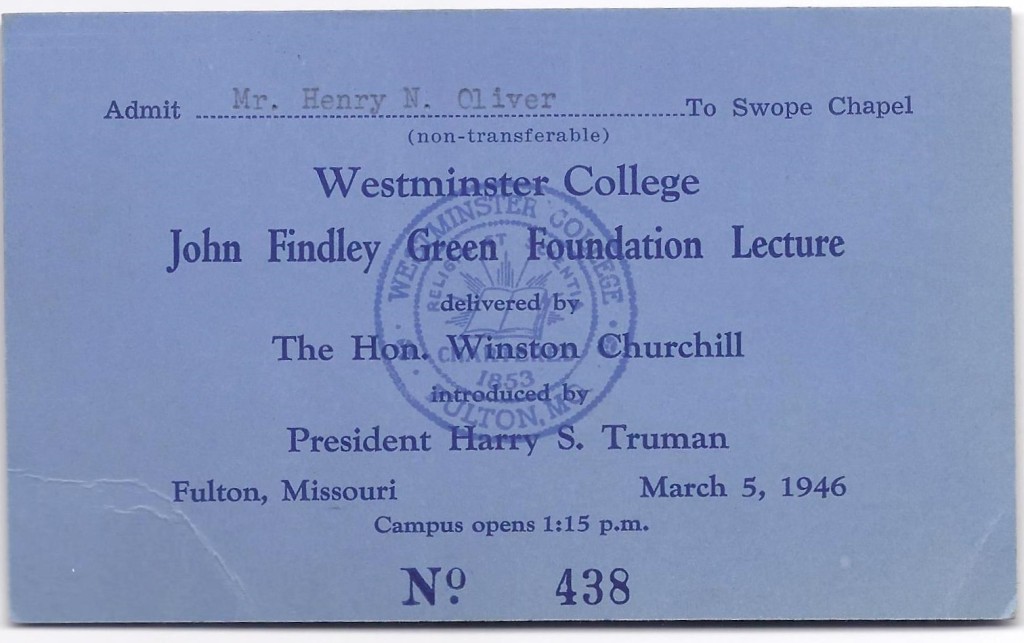

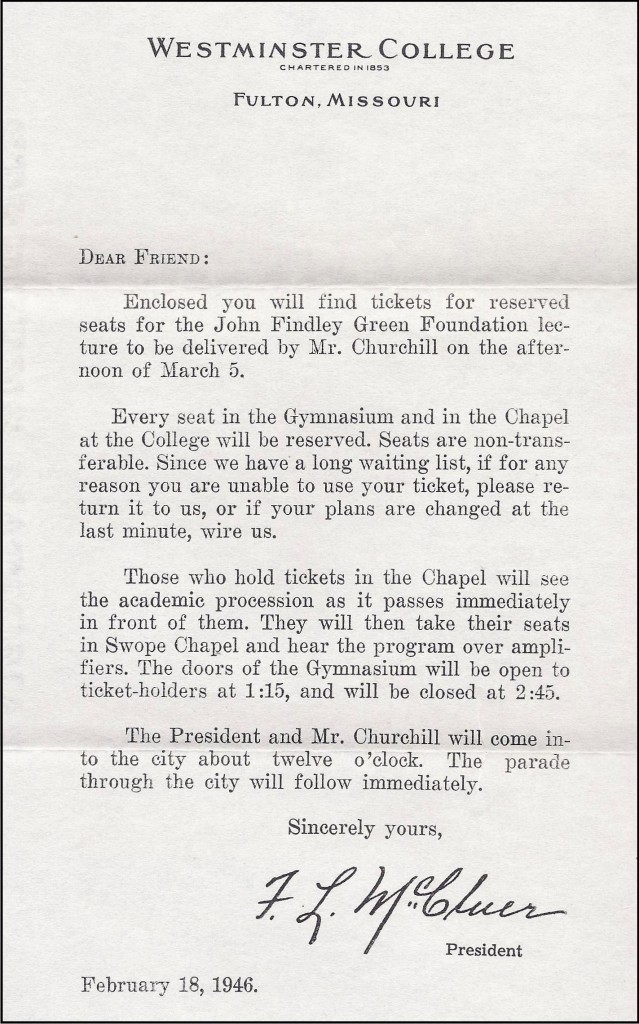

We were excited recently to offer an original ticket to Churchill’s speech, as well as an accompanying invitation letter signed by College President Franc L. McCluer. We had never before offered an original ticket and this is no surprise. In his invitation letter, McCluer specifically stated: “Every seat in the Gymnasium and in the Chapel at the College will be reserved. Seats are non-transferable. Since we have a long waiting list, if for any reason you are unable to use your ticket, please return it to us, or if your plans are changed at the last minute, wire us.”

We were excited recently to offer an original ticket to Churchill’s speech, as well as an accompanying invitation letter signed by College President Franc L. McCluer. We had never before offered an original ticket and this is no surprise. In his invitation letter, McCluer specifically stated: “Every seat in the Gymnasium and in the Chapel at the College will be reserved. Seats are non-transferable. Since we have a long waiting list, if for any reason you are unable to use your ticket, please return it to us, or if your plans are changed at the last minute, wire us.”

Though it is difficult to understand how the holder of this ticket could choose to leave it unused, we can be glad that he did. We were able to provide this ticket to Lee Pollock of The Churchill Centre. And just a few weeks ago Lee presented the ticket and letter to British Ambassador Sir Kim Darroch, who assumed his post in January of this year. The Churchill Centre had partnered with the British Embassy in Washington to create a program entitled “What’s Next for the U.S. – U.K. Partnership?” Following the program and discussion, Ambassador Darroch hosted a celebratory dinner for guests “including senior staff of both Embassies, representatives of the U.S. State Department and selected foreign policy organizations in Washington. After toasting both Ambassadors with Churchill’s favorite Pol Roger champagne,” Lee presented Ambassador Darroch with the framed original ticket and letter we provided to The Churchill Centre.

It was a wonderful way to commemorate both the 70th anniversary of the speech and the relationship that does, should, and must endure.

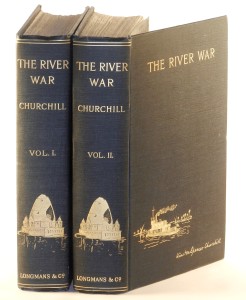

The unity of the English-speaking peoples, particularly Great Britain and the United States – was in many ways Churchill’s political and literary life’s work. Britain’s acute dependence upon the United States during and after the Second World war is well known and very much born of necessity, but Churchill’s conception of what became the ‘Special Relationship’ had roots far earlier in Churchill’s life than the Second World War.

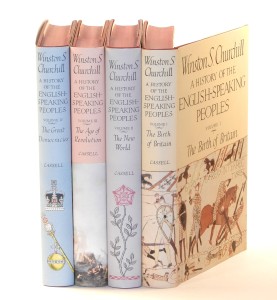

The cultural commonality and vitality of English-speaking peoples animated Churchill from his Victorian youth in an ascendant British Empire to his twilight in the midst of the American century. In fact, Churchill’s great four-volume work, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, was actually drafted in the 1930s. Fittingly, the half a million word draft was set aside when Churchill returned to the Admiralty and to war in September 1939. The war would, of course, pivot on an unprecedented alliance among the English-speaking peoples – an alliance Churchill personally did much to cultivate, cement, and sustain.

The cultural commonality and vitality of English-speaking peoples animated Churchill from his Victorian youth in an ascendant British Empire to his twilight in the midst of the American century. In fact, Churchill’s great four-volume work, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, was actually drafted in the 1930s. Fittingly, the half a million word draft was set aside when Churchill returned to the Admiralty and to war in September 1939. The war would, of course, pivot on an unprecedented alliance among the English-speaking peoples – an alliance Churchill personally did much to cultivate, cement, and sustain.

Churchill, the child of an American mother and descended from British nobility on his father’s side, paid particular heed to the ‘Special Relationship’ between Britain and the United States. Perhaps to some extent he regarded himself as a personification of that relationship. When Churchill first addressed the U.S. Congress on 26 December 1941 he famously quipped, “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.”

Among the English-speaking peoples, Churchill considered Britain and the United States in particular “united by other ties besides those of State policy and public need.” During a wartime speech at Harvard, among the “ties of blood and history” Churchill cited were, “Law, language, literature – these are considerable factors. Common conceptions of what is right and decent, a marked regard for fair play, especially to the weak and poor, a stern sentiment of impartial justice, and above all the love of personal freedom, or as Kipling put it: ‘Leave to live by no man’s leave underneath the law’ – these are common conceptions on both sides of the ocean among the English-speaking peoples” (6 September 1943 speech at Harvard University).

It was of course an emerging great global threat to freedom and rule of law in the form of the ambitions of the Soviet Empire that animated Churchill’s speech 70 years ago in Fulton, Missouri.

The reinforcement and constructive application of the common conceptions of the United States and Great Britain – upon which so much of 20th Century history hinged – would continue to the very end of Churchill’s life and career. Indeed, Churchill’s aspirations for this ‘special relationship’ are encapsulated in the title of his last published book of speeches in 1961, The Unwritten Alliance.

We are pleased that our own special relationship with The Churchill Centre made this gift possible, and we hope that, in some small way, it serves to bolster and perpetuate the special relationship between the two nations Churchill held most dear. If so, it will prove a very special ticket indeed.