Is my book rare or collectible?

How do I sell my book?

Do you want to buy my book?

What is my book worth?

How much will you pay me?

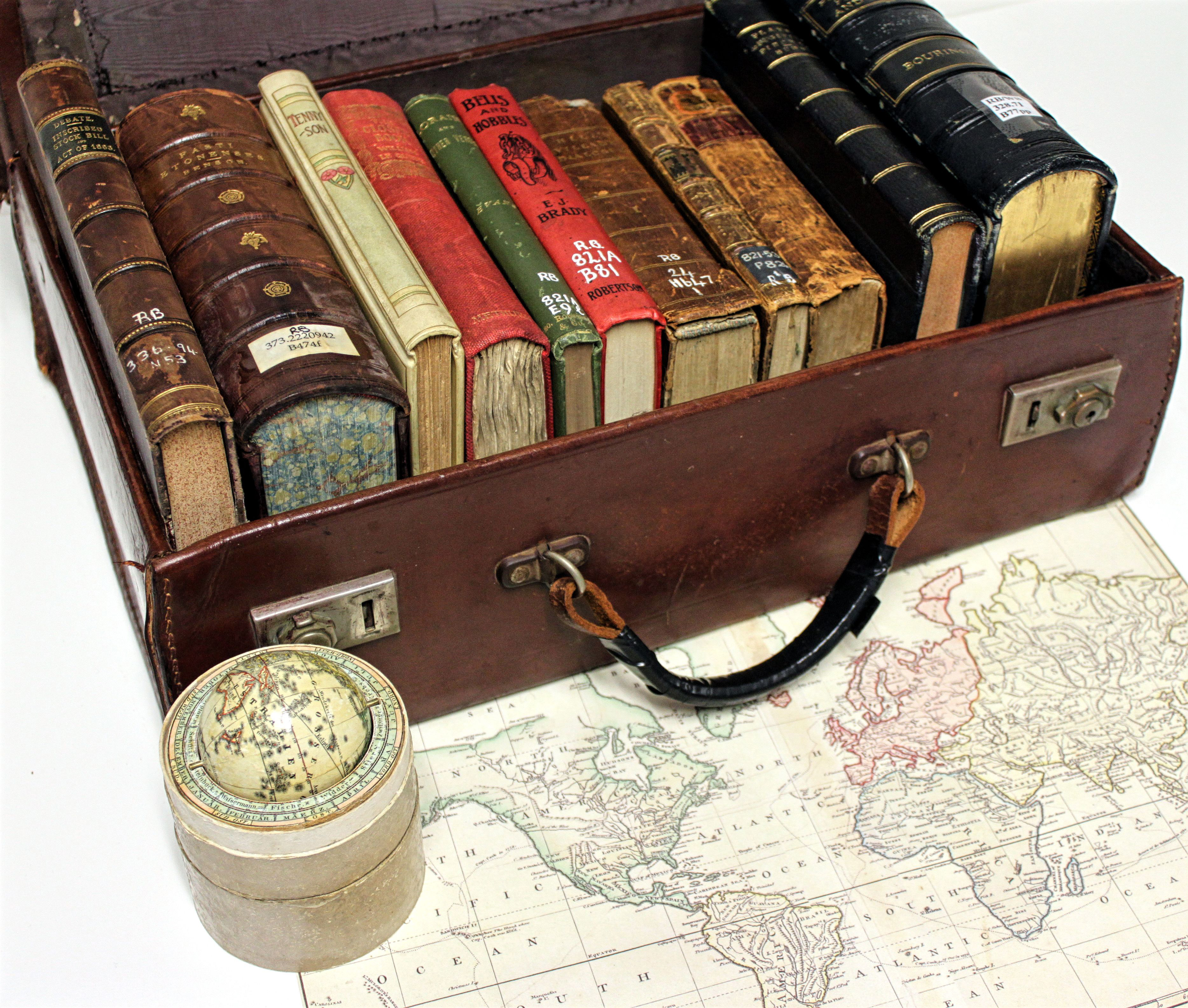

Since we’re booksellers, we’ve been asked all of these questions. Many times. Because a tremendous number of factors are involved, the only universally applicable answer is “It depends…” Nonetheless, it seems long past time to write a bit about what makes books precious.

I say “precious” to acknowledge the curious passions and peculiarities that inform book collecting. Old does not necessarily mean valuable. I might have a 400+ year-old Latin treatise on Roman law that takes years to sell and fetches only a few hundred dollars. Or I may have a first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone that’s less than half my own age and yet will sell quickly and fetch enough to buy a car. A really, really expensive car. The kind of car you’d be afraid to park at the grocery store.

So is value a matter of scarcity? No, not necessarily. We’ve sold items of which only a handful of copies are known for 10x less than items of which there are more than 1000x as many surviving copies. Is that confusing? Tell me about it. But I’ve got to get us past some of the “It depends”. So here goes.

THE BIG THREE

Have you ever bought a diamond? I did. Only once, thankfully. I remember trying to study up in advance for my parley with various diamond merchants. As a layman, it all came down to three big, overarching factors – cut, color, and clarity. Granted, there were a daunting number of additional factors, but the big three helped me orient to the market.

The good news is that there’s a similar big three for books. Generally speaking – albeit with a significant number of exceptions – the factors in determining a book’s value are:

Edition

Printing

Condition

Of course, there are a legion of devils in the details. Let’s tackle a few.

FIRST, WHAT’S A “FIRST EDITION”?

“First edition” is the holy grail for most collectors. Behind that collecting goal and simple definition is a simple wish – to have a copy of the author’s work as it first appeared, by itself, between its own covers (i.e. not serialized in a magazine, etc.). But “First edition” is a far more complicated label than it seems.

WHEN IS A “FIRST EDITION” NOT REALLY FIRST?

Technically speaking, an edition is all copies of a book printed from the same setting of type. Later editions begin only when there are substantial changes made to the text or a new publisher takes over. But there can be many printings (also called “impressions”) of a first edition.

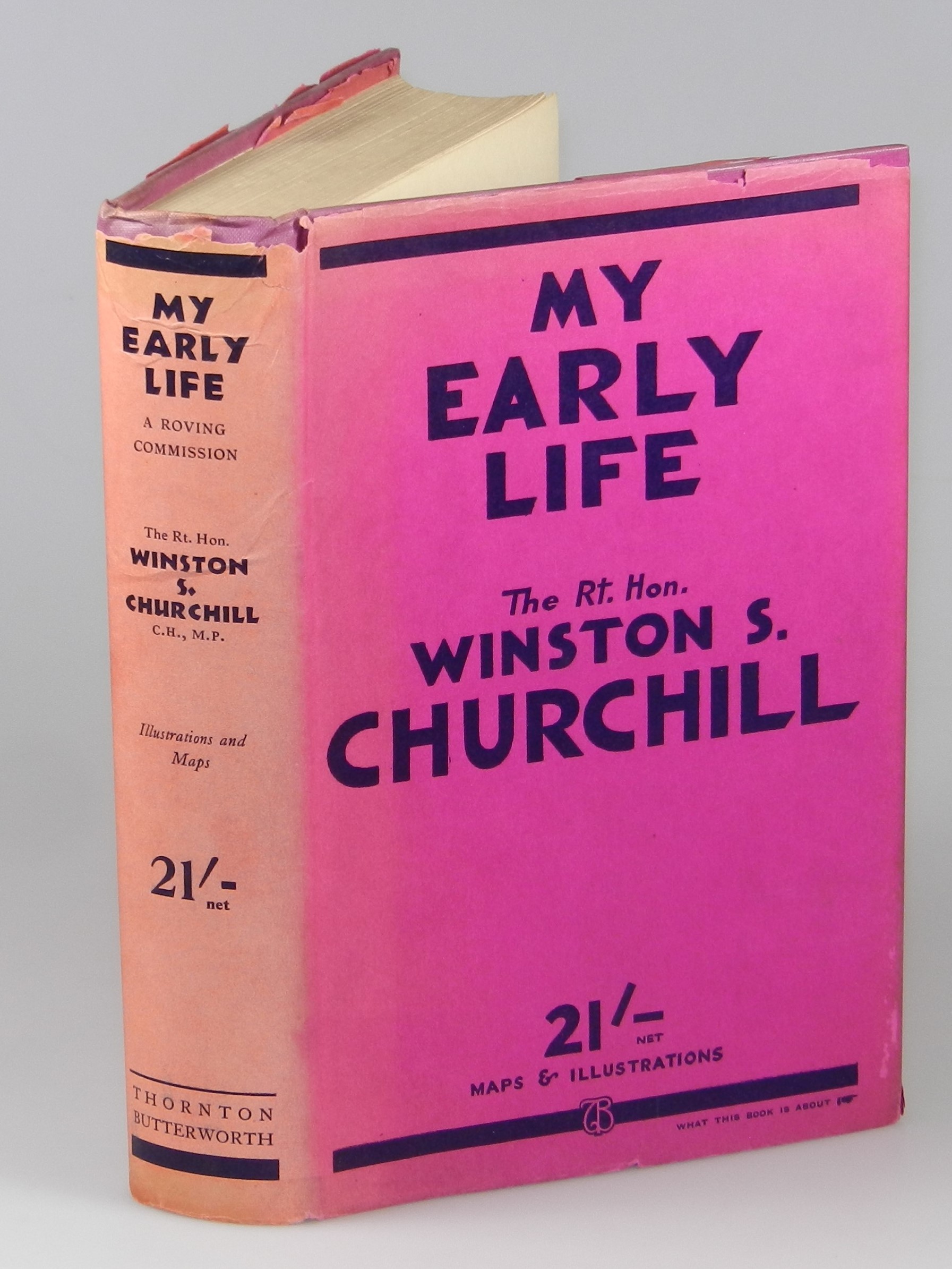

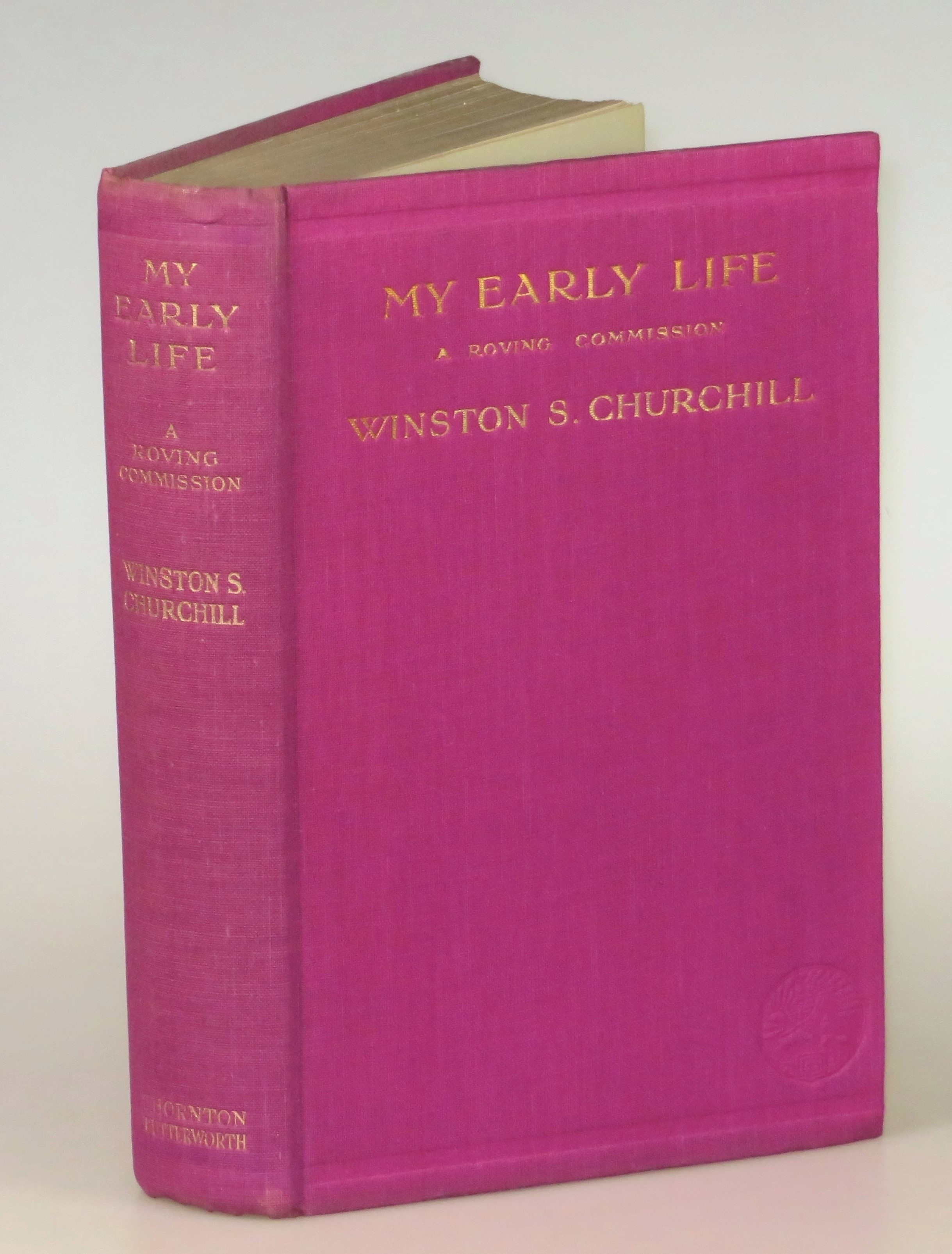

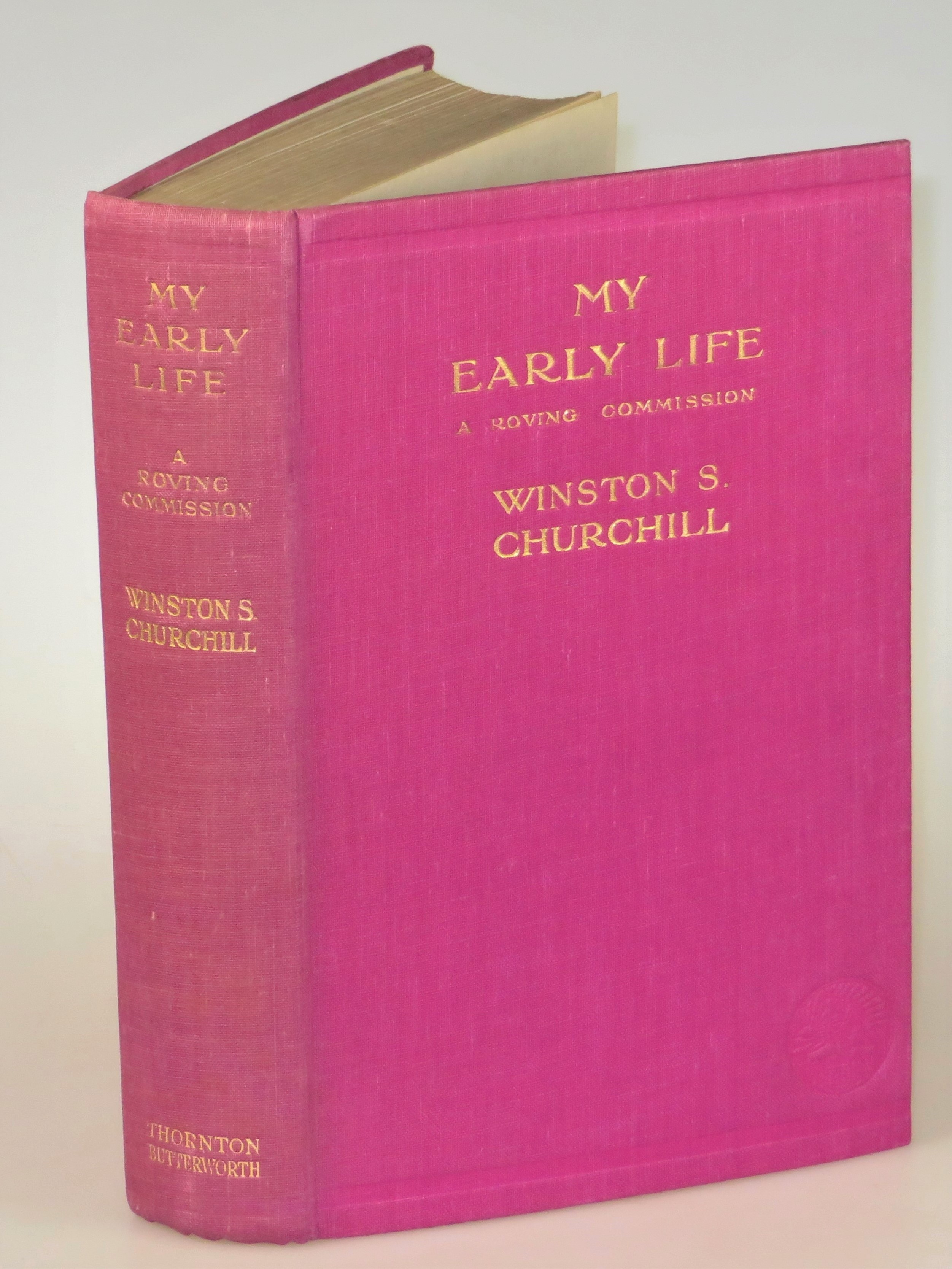

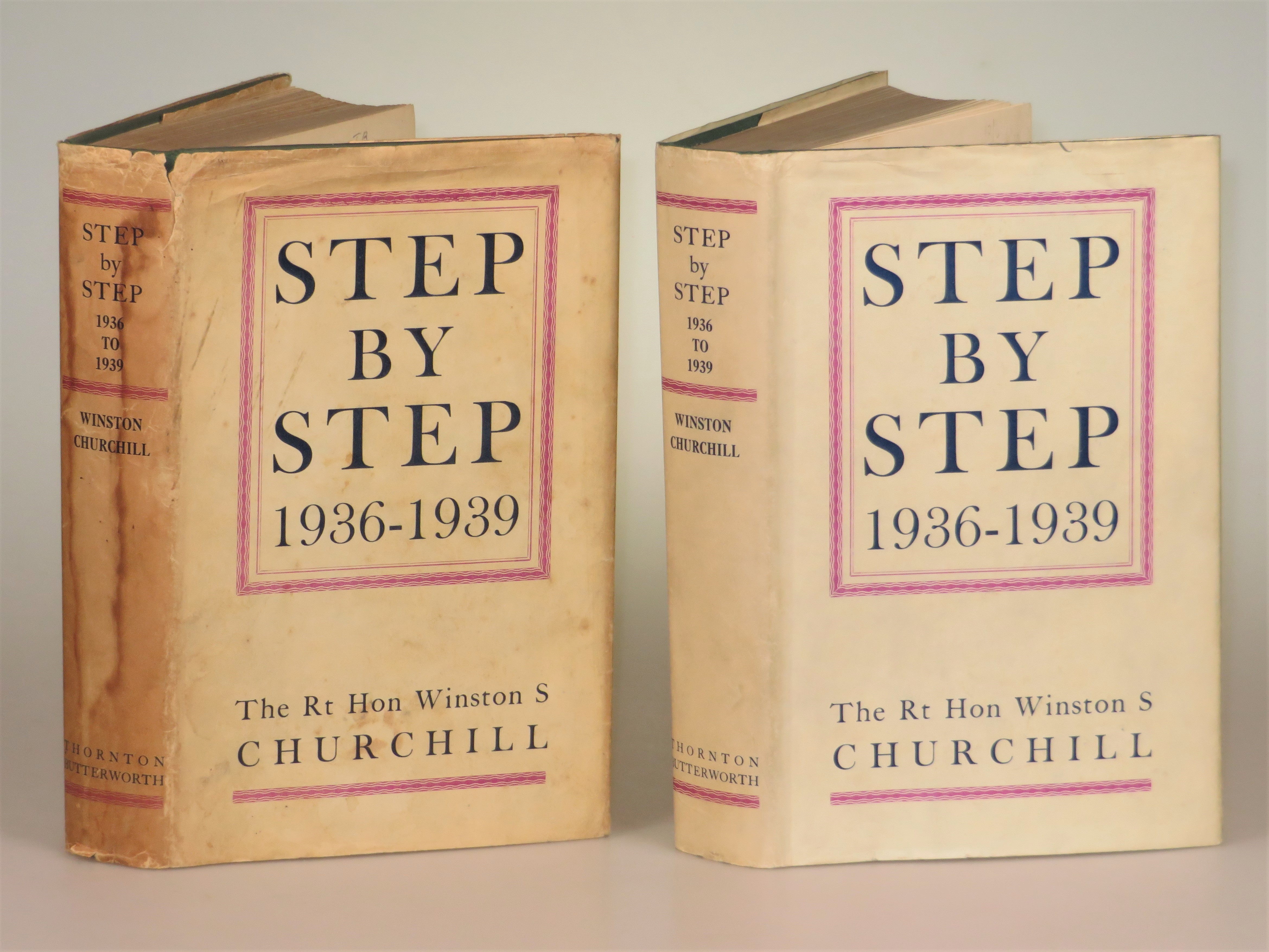

Here’s one of many scenarios. Winston’s Churchill’s only work of pure autobiography – My Early Life – was first published in October 1930. That was the first printing of the first edition. But pre-publication demand was so strong for the book that a second printing was ordered by the publisher before the first printing was even published. The book sold well, so the publisher kept cranking them out; there were ultimately six printings of this first edition spanning a decade between October 1930 and December 1940. All of these are legitimately first editions. But it is likely the first edition, first printing that you really want – and probably what you really mean when you say “First edition”.

STATES? THERE CAN BE STATES, TOO?

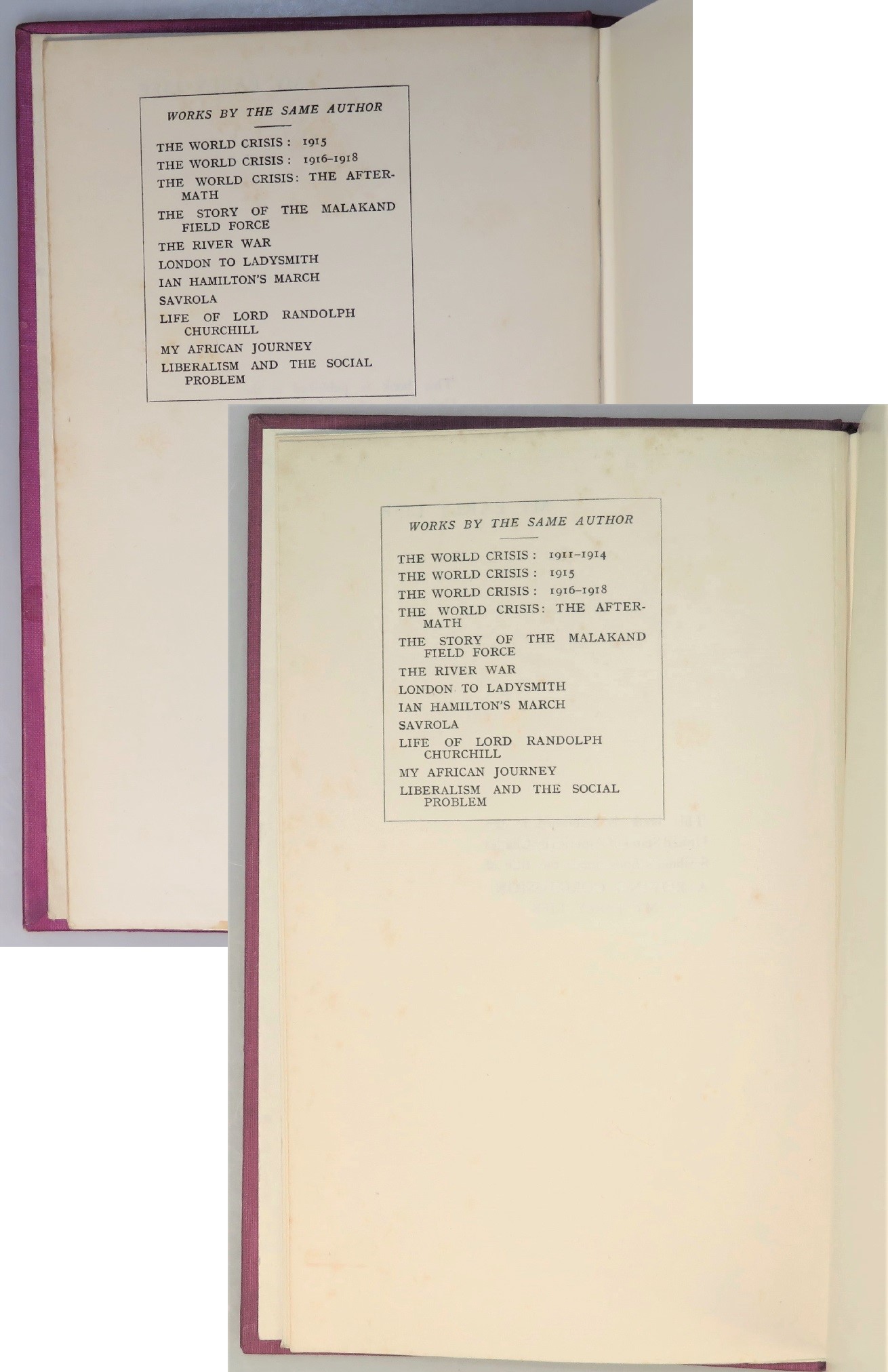

Just in case that’s not complicated enough, one first printing can be more first than another. Yeah. There can be different “states” of a first edition. Let’s say the printer notices a small error – like a punctuation mark or a page number or a missing book title in a list of other works by the author – and corrects this error during a print run. Or let’s say the publisher used a certain texture of cloth to bind part of the first printing but then ran out or changed their mind and started using a different cloth. Or let’s say they altered the layout of the title on the front cover during a print run. Then whatever came first becomes the first state of the first printing of the first edition. Whichever is more first is more desirable and valuable.

For Churchill’s My Early Life, there is a first state of the first printing of the first edition, identified by a minor text omission in the prelims corrected during the first printing.

There are also multiple binding states, because for the first printing the publisher used two different textures of binding cloth and stamped the title on the front cover in two different layouts.

Confused? Wait, there’s more!

Back to that Churchill book. As byzantine as it sounds, we have two factors going for us. First, the publisher at least did us the courtesy of denoting “Second Impression”, “Third Impression” and so forth on the copyright pages of subsequent printings. Second, someone went through the trouble of writing an extensive bibliography about Churchill’s published works, which enumerates what we call “issue points” of each printing and the various states thereof.

SO HOW DO I KNOW IF I HAVE A FIRST PRINTING OF A FIRST EDITION?

It’s often not easy. Publishers differ vastly in how – or even whether – they denote first editions and various printings. Some make it easy for us, printing “first edition” or even “first printing” right there on the copyright page. Some are a little less clear but still decipherable, using a number code to denote various printings of the first edition. Some publishers use more arcane methods with no easy or universal way to distinguish between editions and printings.

It can get worse. Publisher’s make mistakes, sometimes conflating the terms “edition”, “printing”, and “impression”, so that even when you see the actual words “edition” and “printing” and “impression” right there in black and white on a copyright page, you cannot necessarily trust their accuracy. Yes, sometimes the publisher is wrong. Then it is up to professional booksellers, expert collectors, and bibliographers to sort out the actual publishing history. Moreover, sometimes an individual publisher will change how they designate editions and printings, so even if you know what method the particular publisher used to denote publishing history, you must also know when they used that particular method. Denotation methods among publishers have changed and will continue to change over decades and centuries.

CONDITION CONDITION CONDITION!

If you’ve ever shopped for a house, you’ve probably heard a real estate agent say “Location Location Location.” Condition Condition Condition is the rough equivalent for collectors and booksellers.

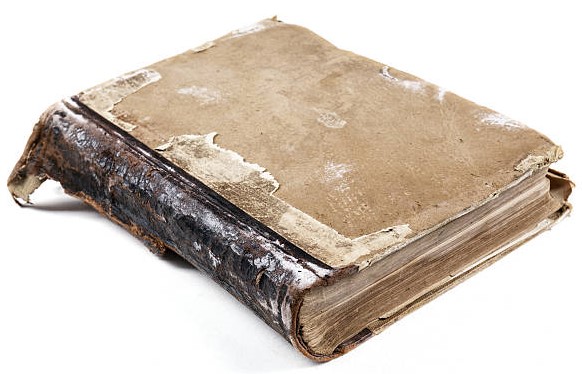

First, we need to acknowledge the underlying madness – or, to be kinder, the deep irony – of book collecting. Books are inherently perishable objects created to be consumed. As we’ve written before, books are a tenuous combination of perishable materials and discordant chemistry – paper and glue and string and cloth, material animal, vegetable, synthetic, or all of the above, all of which conspire to decohere almost from the moment they’re bound together.

Under most circumstances, people are supposed to help books decohere. By fulfilling a book’s purpose – actually reading it – you accelerate the inevitable deterioration. Every time you merely open a book, you kill it just a little, letting in a little moisture or dust or finger oil, stressing the binding, pulling the head of the spine, creasing page corners… And that’s how it should be. If books have a single purpose, it is to encapsulate and convey the distilled perspective of another consciousness, and in so doing to be read and read until they’re wrecked.

But that’s not what most collectors want. They want the precious few books that did not suffer the depredations of actually being read. The more unblemished the better. Better still, unread.

I know. I know. But it does make a certain sort of sense in context. If the whole point of a first edition is a sort of communion with the very first time the words were printed and bound together, then it makes sense that there would likewise be a desire to feel like this book has been waiting, in a patient state of special preservation, for you.

Accepting this particular sort of madness for what it is allows you to understand (1) that condition is paramount and (2) that small gradations in condition can translate to considerable differences in value.

In general, for a collectible first edition to be of maximum value, it needs to be in excellent condition, as close to original as possible. If there was originally a dust jacket and that jacket is missing, that can make a stupefying difference in price. Spotting or soiling or some previous owner’s name written inside are all strikes against value. If the book or dust jacket has been repaired – even if it has been repaired professionally – that’s likely a significant mark against it, too.

Think of it this way – most of us would prefer a new car to a used car. Even though we are going to drive it ourselves. Even though the purpose of a car is to be used. Even though the age and mileage we put on a car will incrementally, inevitably ruin it. We still want it all shiny and low mileage if we can get it. And if we are considering a used car, we don’t consider dents and dings and seat stains from previous owners as desirable selling points. As for repairs… once a car has been in a serious accident and then salvaged with repairs, its title is legally changed and all future sellers must disclose that it’s been salvaged. Most people don’t want a salvage-titled car and those willing to buy one expect to pay a whole lot less for it. Much the same is true of books.

THE CONDITIONAL MEANINGS OF CONDITION TERMINOLOGY

Booksellers use a gradation of terms to describe the condition of a book. These grades generally include, in descending order, as new, fine, very good, good, fair, and poor. But there are two problems with this system. One is that, since it is inherently subjective, one bookseller’s grading can differ significantly from another’s, not even factoring in the obvious incentives to grade a book as better than it actually is. Second is the fact that even the ostensibly straightforward condition terms used by professional booksellers can be misleading. Grades of “As new”, “Fine” and “Very good” are relatively self-explanatory, but “Good” actually means quite worn and not so good, “Fair” means bad, and “Poor” means that you should keep this book on hand just in case there’s another pandemic and you run short of toilet paper.

PROVENANCE, OR HOW TO TRUMP EDITION, PRINTING, AND CONDITION

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about the how the big three – edition, printing, and condition inform the desirability and value of a book. Now it’s time to contradict myself. Sometimes edition, printing, and condition take a back seat to provenance.

“Provenance” is the fancy bookseller term for a book’s history – the details of who’s owned it, where it’s been, and what it’s been up to since it was published. This typically manifests in the form of “extra ink”, by which we mean words, numbers, or notation of some sort applied to the book after it was published. Most of the time provenance is pedestrian, and either diminishes value or is neutral. A previous owner name and address written on the endpapers. A small stamp or sticker from a bookseller affixed to the rear pastedown or the front flap of a dust jacket. That sort of thing. But…

A collectible book is valued as a physical piece of history. When you can add more compelling history to the book, the book naturally becomes more valuable. What do I mean? When an author signed or inscribed a book. If a previous owner was famous, or, even better still, both famous and connected with the author. If the book was demonstrably present at an interesting, relevant, or important place and time. These sorts of things can dramatically enhance the story, value, and appeal of a book as a physical artifact.

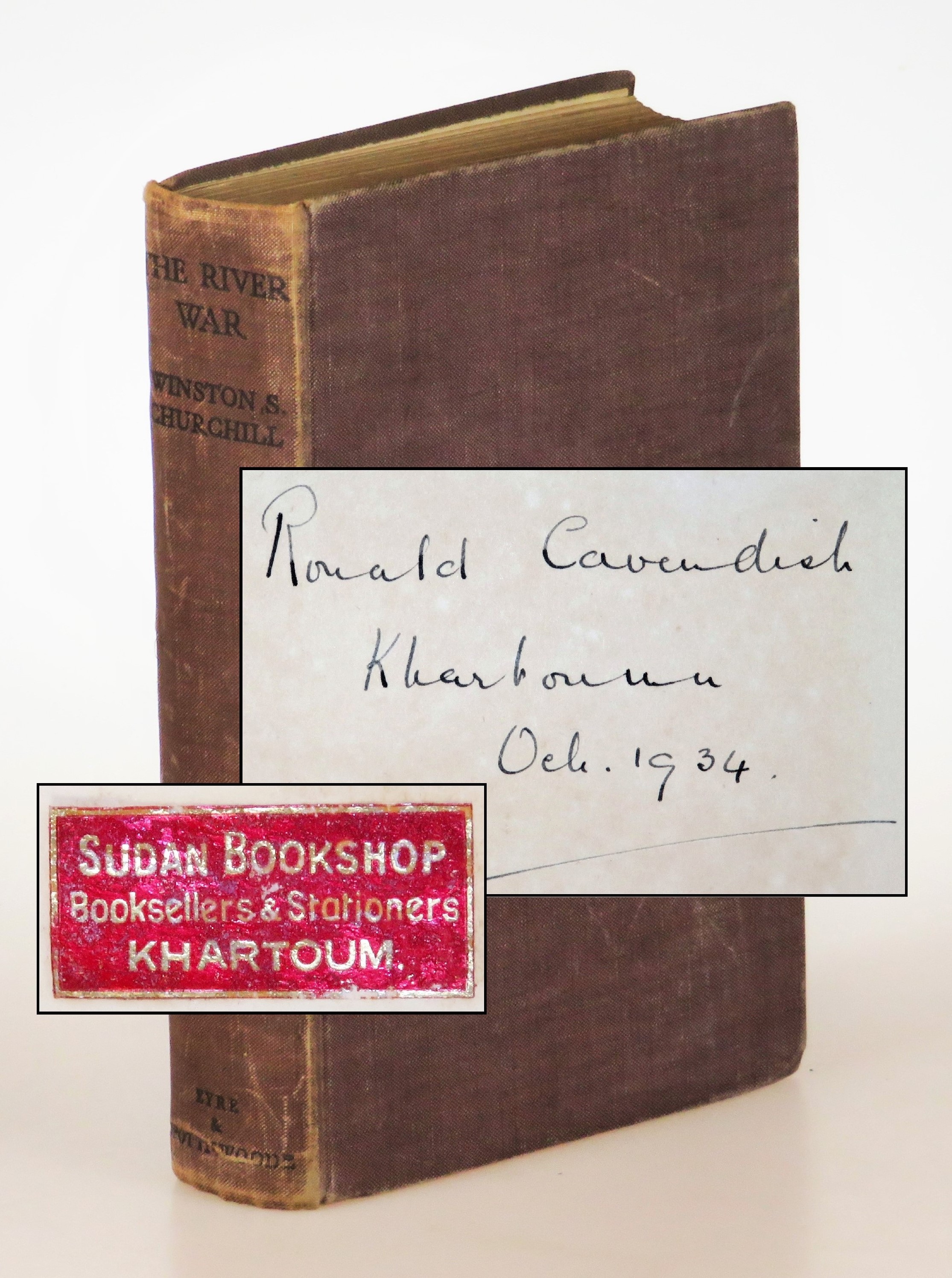

A few examples may help. We once had a worn copy of the 1933 third edition of The River War by Churchill. This third edition was abridged and published a third of a century after the first edition. Moreover, this copy had lost its original dust jacket and was considerably soiled and worn. Ordinarily we’d not even bother offering it for sale. But this copy had been owned by a hero of both World Wars who died gallantly in the field during Churchill’s wartime premiership. And this copy had been purchased in 1934 by this same soldier from a Sudanese bookseller in Khartoum – the epicenter for the events that led to the titular River War. This became a case where the provenance actually became worth significantly more than the inherent value of the book itself.

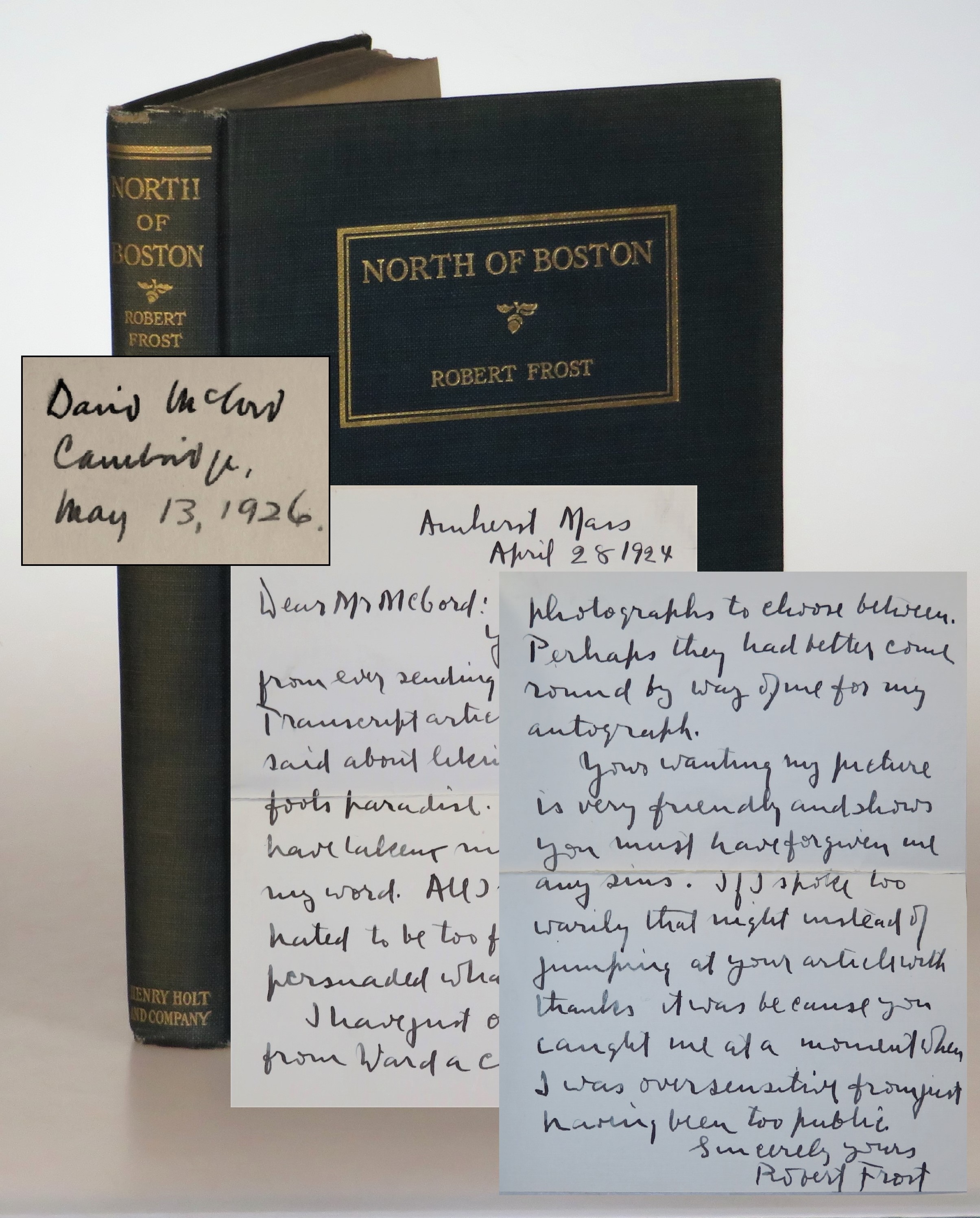

Another such case was a later printing of the American edition of Robert Frost’s second published book – North of Boston. Normally, a later printing of the American edition of this book is not a value proposition. The true first edition was published in England, preceding the American edition. And this copy was not the first printing, had lost its dust jacket, and was a bit worn. As if to make things even worse, the publisher had incorrectly designated this as “Third edition” on the copyright page, even though this was actually the second printing of the first American edition. So why did we bother offering this book? Because this humble and confused second printing of the first American edition had belonged to the author’s friend and fellow poet David McCord. The book featured both McCord’s dated ownership signature and a 28 April 1924 autograph letter from Frost to McCord referencing a review McCord had written about New Hampshire – Frost’s first book to win a Pulitzer Prize. McCord’s late 1923 review is actually published on the Pulitzer website. Another case of the value of provenance far exceeding the value of the book itself.

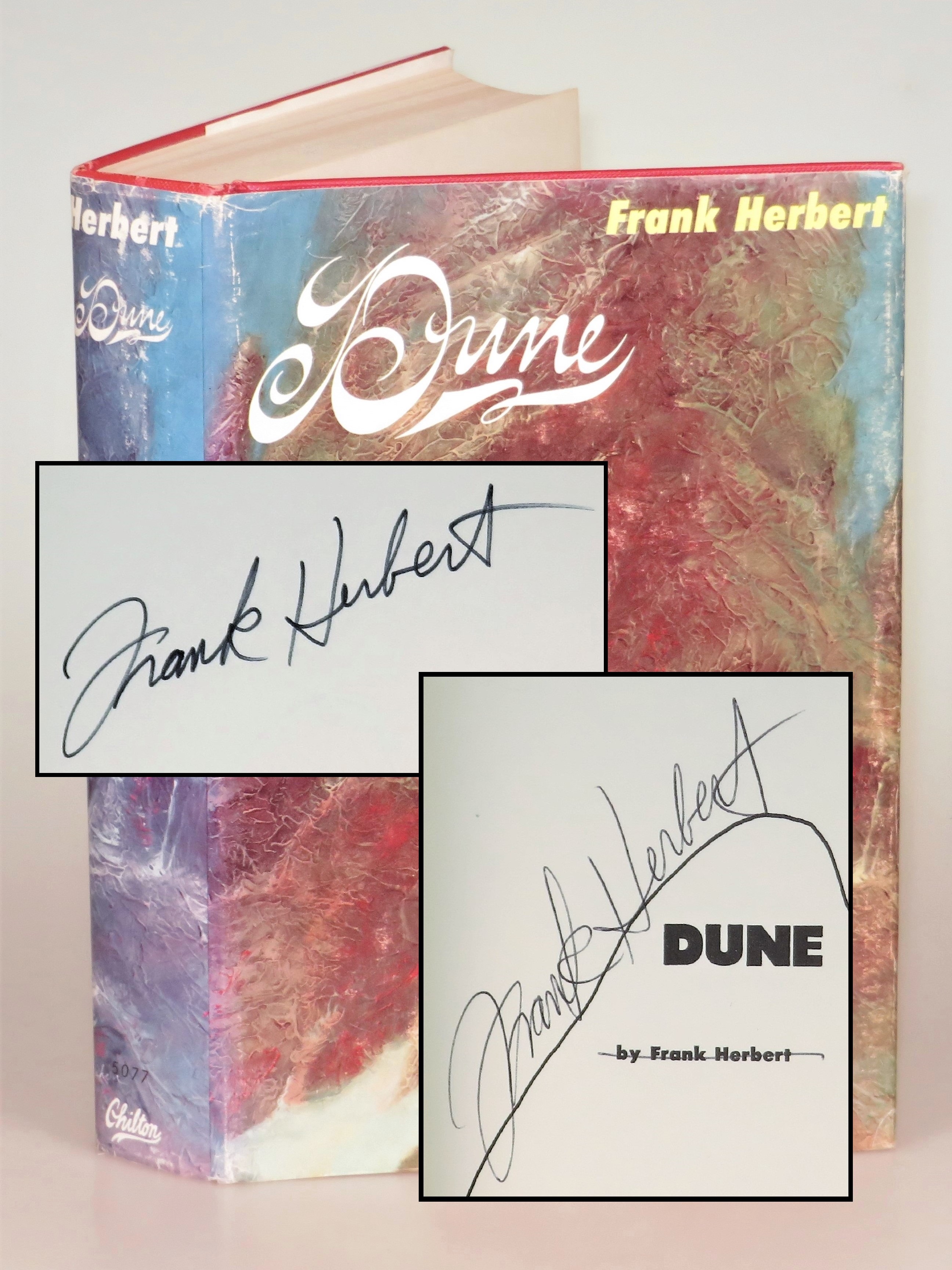

A more straightforward example came to us just a few days ago. The first edition, first printing of Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction masterpiece, Dune, is legendary. After being repeatedly rejected, Dune was first published by Chilton – a publisher best known for auto repair manuals. Dune went on to win the Hugo and Nebula Awards and has seen film adaptations and enduring acclaim. Dune also went on to multiple printings, Chilton issuing new printings of the first edition well into the 1970s. A first printing of the first edition can be worth many thousands, later printings some hundreds. A sixth printing of the first edition is typically not exciting. But this sixth printing is signed by Herbert. Twice.

COMPELLING NON-FIRST EDITIONS

Don’t fret if your book is not a first edition and nobody interesting scribbled in it. First editions are the primary focus of many collectors, but they are by no means the sole focus. And provenance is not the only way to render a non-first edition compelling.

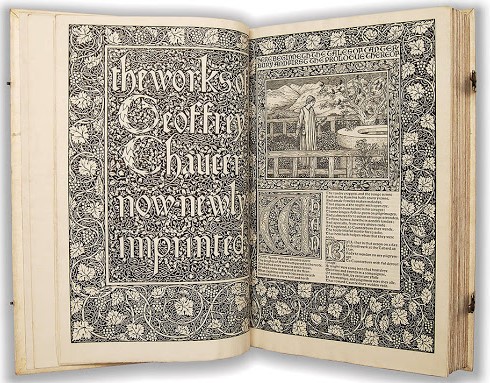

There are hosts of later editions that end up being quite coveted by collectors. Pretty much any of the hand-made books produced by the Kelmscott Press in the late 1800s are quite desirable and valuable indeed. If you have a Kelmscott Chaucer or Shakespeare, you definitely don’t have a first edition – and you definitely do have a very precious book. The first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses was published in Paris in 1922. But if you have the 1935 edition published by the Limited Editions Club in New York, you have a very valuable non-first edition. This 1935 edition was illustrated and signed by Henri Matisse. And make sure you look carefully, because some were signed by Joyce, too. There are myriad fine, limited, collected, commemorative and other editions of works by authors that are not first editions but nonetheless valuable.

TAKEAWAYS FROM ALL THIS?

That valuing collectible books is complicated and depends on a variety of mutually influencing and sometimes seemingly disparate factors. That appropriately identifying and assessing these factors requires a little intuition, a little alchemy, and a lot of experience. That the market for rare books is just as ancient, enduring, and capriciously evolving as the learnings, loves, and lusts that drive us to possess books. That even nearly 3,000 words on the subject just scratches the surface. But that despite all of this complexity and arcanum, there are some identifiable signposts and considerations, some of which we hope you found in this post.

WHAT IF I’M THINKING OF SELLING MY BOOK(S)?

We’ve just implemented an effort to make it easier for you to ask us to consider your book(s). Please see our new SELL TO US page on our website, which includes a straightforward, easy to complete submittal form.

One final question to address before we finish writing:

BUT YOU ARE A SAN DIEGO BOOKSELLER AND I LIVE IN… HOW DO WE MAKE THIS WORK?

We buy and sell books in dozens of nations spread over six continents (Sorry Antarctica!). Chances are that we have sent or received valuable books from someplace way more exotic than where you live. With email and digital images we can typically accomplish much of the communication we need to consider a book or collection. And international shipping is, in our experience, safer than rush hour traffic or a COVID-19 trip to the grocery store.

Cheers!

2 thoughts on “Do I have a valuable book?”