A book can be a counterintuitive object. An array of tidy print between two covers neatly gilt-stamped with a proprietary author’s name belies the messy process of planning, writing, re-writing, emending, and further revising that actually makes any body of writing worth reading. Precious few authors accomplish the tasks alone. A veritable legion may be involved in publishing a book, including researchers, editors, agents, designers, lawyers, publishers, printers, and publicists. Moreover, the effort may continue long after initial publication.

All of this is particularly true of a monumental work like Churchill’s The Second World War. A recent find, a copy of The Hinge of Fate from the Cassell and Company archives, helps pulls back the curtain to reveal the ongoing time and labor that goes into publication. It also reveals a little-known story from Churchill’s second Premiership about a real-life Hemingway character who threatened to sue Churchill for libel.

Cassell served as Churchill’s primary publisher for the final quarter century of his life, from 1941 on. As early as 1939 – before he was even Prime Minister – Churchill was courted by publishers for the enticingly lucrative rights to publish any post-war memoirs. When Newman Flower of Cassell secured publication rights to Churchill’s war memoirs, it was “perhaps the greatest coup of twentieth century publishing.” Churchill’s post-war literary output, particularly the six volumes of The Second World War, proved the essential asset to Cassell’s postwar recovery.

Publication of the first volume, The Gathering Storm, was held up with constant corrections – despite which the first edition contained a number of errors. Among the most embarrassing was a description of the French Army as the “poop” rather than the “prop” of France (rendered doubly problematic by proximity to truth). Although a capable team of proofreaders was engaged for the subsequent volumes, their efforts were not exhaustive, as evidenced by the number of corrections marked in this copy of the fourth volume.

This volume, stamped “Editorial”on the front free endpaper and top edge, was a part of the Cassell and Company archives and features 55 handwritten emendations.

This volume, stamped “Editorial”on the front free endpaper and top edge, was a part of the Cassell and Company archives and features 55 handwritten emendations.  Accompanying the volume are 14 oversized, single sided galley sheets, as well as a loose copyright page with corrections for the “Fourth edition, third impression August 1977”. This copy of the first edition was used in Cassell’s editorial department until at least 25 May 1977.

Accompanying the volume are 14 oversized, single sided galley sheets, as well as a loose copyright page with corrections for the “Fourth edition, third impression August 1977”. This copy of the first edition was used in Cassell’s editorial department until at least 25 May 1977.  We have confirmed that handwritten corrections made within this particular volume were incorporated into later printings and editions. The edits range from simple corrections of letter cases to fixing misspellings to rewording sentences.

We have confirmed that handwritten corrections made within this particular volume were incorporated into later printings and editions. The edits range from simple corrections of letter cases to fixing misspellings to rewording sentences.

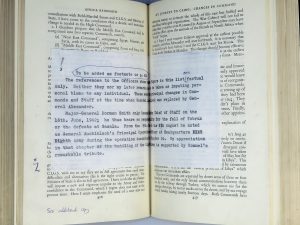

One particular edit merits a highlight. At page 416 a typewritten sheet is laid in bearing additional copy for a footnote added in later editions. The story of this footnote involves a Second World War General fired by Churchill.

One particular edit merits a highlight. At page 416 a typewritten sheet is laid in bearing additional copy for a footnote added in later editions. The story of this footnote involves a Second World War General fired by Churchill.

Eric Edward Dorman-Smith (1895-1969) served in the First World War with distinction, wounded three times and awarded the Military Cross for his efforts in the trenches of Ypres. Dorman-Smith was nicknamed “Chink” due to his resemblance to the Chinkara antelope mascot of his WWI regiment. On Armistice Day in Milan, Chink met Ernest Hemingway, who had been wounded on the Italian Front while serving with the Red Cross. Chink’s wartime heroics, coupled with his chivalrous demeanor and immaculately dressed image, encapsulated Hemingway’s conceptions of war and honor. They became friends, and Hemingway would later use Chink as the basis for the character Colonel Richard Cantwell, the hero of Hemingway’s novel Across the River and Into the Trees.

After the war Chink split the 1920s between Paris – where Hemingway introduced him to James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and the rest of the city’s literary intelligentsia – and instructing at Sandhurst and Staff College Camberley. At Camberley, Chink scored 1000 out of 1000 on his tactics entrance paper, a record. At the onset of the Second World War, he was positioned as the director of military training in India and was soon transferred to the Middle East Staff College in Haifa. Despite a position that he derided as a “schoolmaster’s role”, Chink’s tactical advice played a key role in Italy’s defeat at Beda Fomm.

After the war Chink split the 1920s between Paris – where Hemingway introduced him to James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and the rest of the city’s literary intelligentsia – and instructing at Sandhurst and Staff College Camberley. At Camberley, Chink scored 1000 out of 1000 on his tactics entrance paper, a record. At the onset of the Second World War, he was positioned as the director of military training in India and was soon transferred to the Middle East Staff College in Haifa. Despite a position that he derided as a “schoolmaster’s role”, Chink’s tactical advice played a key role in Italy’s defeat at Beda Fomm.

1942 Auchinleck assumed command of the Eighth Army, and Dorman-Smith was promoted to acting major-general. He would hold the position for only three months. In August 1942 Winston Churchill ordered the “Cairo purge” – a complete restructuring of the Middle East command. Montgomery replaced Auchinleck and Dorman-Smith was given command of a brigade in Italy before being dismissed and involuntarily retiring in 1944. Disgraced and disillusioned, Dorman-Smith returned to his home in Ireland and changed his name to “O’Gowan”. He would implausibly transition from British General to Irish nationalist and IRA supporter.

1942 Auchinleck assumed command of the Eighth Army, and Dorman-Smith was promoted to acting major-general. He would hold the position for only three months. In August 1942 Winston Churchill ordered the “Cairo purge” – a complete restructuring of the Middle East command. Montgomery replaced Auchinleck and Dorman-Smith was given command of a brigade in Italy before being dismissed and involuntarily retiring in 1944. Disgraced and disillusioned, Dorman-Smith returned to his home in Ireland and changed his name to “O’Gowan”. He would implausibly transition from British General to Irish nationalist and IRA supporter.

In 1953 O’Gowan’s solicitor sent a letter to 10 Downing Street claiming that the Prime Minister’s book The Hinge of Fate was libelous. Despite only one reference to Dorman-Smith by name in the book, the letter claimed that Churchill had made “very grave charges that our client was incompetent and perhaps worse and that he was fired for incompetency.” Churchill’s offense was mentioning “General Dorman-Smith to be relieved a Deputy C.G.S.” in the general context of “disasters… in the Western Desert…”

O’Gowan né Dorman-Smith apparently employed his lawyers “all over the place, sent out for everything from slight disappointments in newspaper articles, to local affairs, such as destruction of heritage sites and water pollution in Cootehill.” Nonetheless, Churchill was advised by Sir Hartley Shawcross (the lead British prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal) that the cited passages could plausibly be read as defamatory. Defending a libel case might require making sensitive documents public. Shawcross arranged for Alanbrooke and Montgomery to testify against O’Gowan.

The need never manifested; the trial never went to court. In early 1954, O’Gowan suddenly backed down from his demands. O’Gowan’s biographer claimed Churchill’s advisor called on O’Gowan’s sense of chivalry by informing him of the Prime Minister’s stroke in 1953 and warning that the affair may cause a second, fatal stroke. The matter was settled by the inclusion of a footnote in future editions of the book – the typed manuscript of which is laid in this volume.

This unique copy of The Hinge of Fate may be viewed HERE.