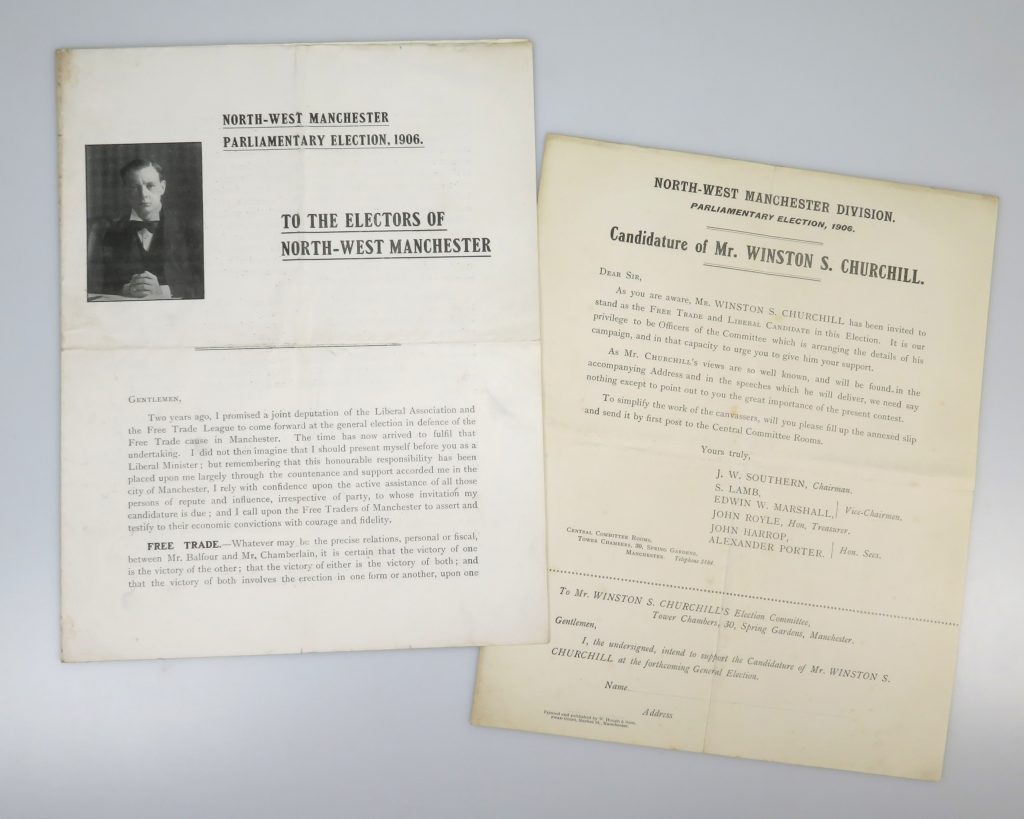

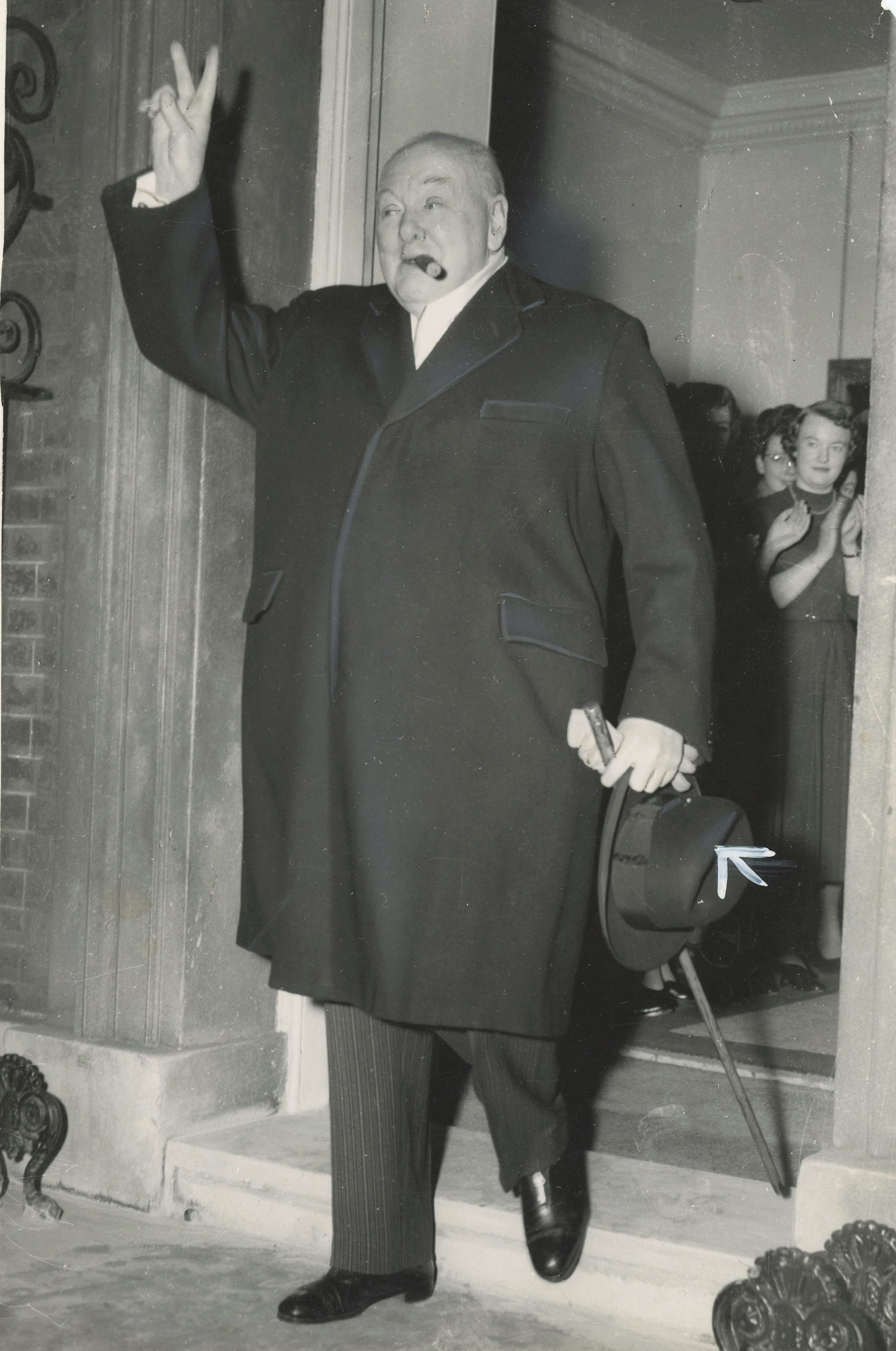

Recently we had the privilege of acquiring a compelling artifact from the first political campaign Winston S. Churchill contested as a Liberal in January 1906. This extravagantly rare leaflet publication – potentially unique thus – is the first edition, only printing, of Winston S. Churchill’s Address to the Electors of North-West Manchester, published on 1 January 1906 specifically in preparation for his campaign.

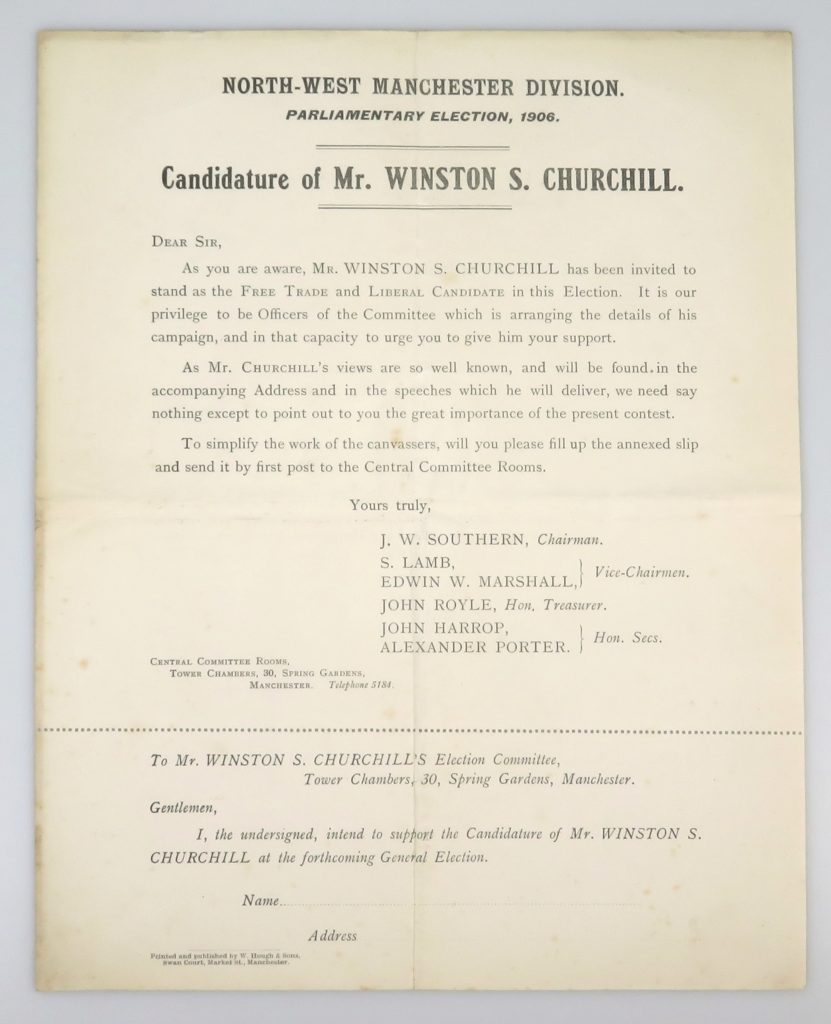

Of the three copies known to us, this is the only privately-held copy of the four-page leaflet. But this is the sole known to retain the canvassing leaf insertion inviting “the undersigned” to declare intention “to support the candidature of Mr. WINSTON S. CHURCHILL at the forthcoming General Election.”

The single-sheet, perforated leaflet insert is clearly meant to accompany Churchill’s message. The upper two thirds is a message from the local Liberal committee introducing Churchill as a “Free Trade and Liberal Candidate”, urging support for him, and stating “Mr. Churchill’s views… will be found in the Accompanying address… To simplify the work of the canvassers, will you please fill up the annexed slip and send it by first post to the Central Committee Rooms.” The bottom portion is perforated, meant for detachment, signature, and submittal in declaration of support for Churchill’s candidacy. The solicited voter is asked to append their signature and address to the statement “Gentlemen, I, the undersigned, intend to support the Candidature of Mr. WINSTON S. CHURCHILL at the forthcoming General Election.” Both the leaflet and insert state “Printed and published by Wm. Hough & Sons” of “Swan Court, Market Street, Manchester.”

In the first days of 1906, Winston Churchill was 31 years old. Already he had been in Parliament for half a decade. Yet already he was on his second political party.

On 31 May, 1904, Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. That year, the Liberal candidate for North-West Manchester died and the MLF noted that “it is hoped that in the immediate future another name may be put before the North-West Division.” It would be Winston S. Churchill.

On 2 January 1906 he published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal. Churchill’s party defection was on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. “…I have changed my Party… I am proud of it. When I think of all… Lord Randolph Churchill gave to… the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated… I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them…”

Churchill arrived at Manchester on 4 January 1906 to campaign; this election address had already been published on 1 January. “It was a sober and realistic statement of the Government case and of the general failure of the Tories in the previous Parliament. His strongest arguments turned on the case for Free Trade”. (RS, Vol. II, pp.114-5)

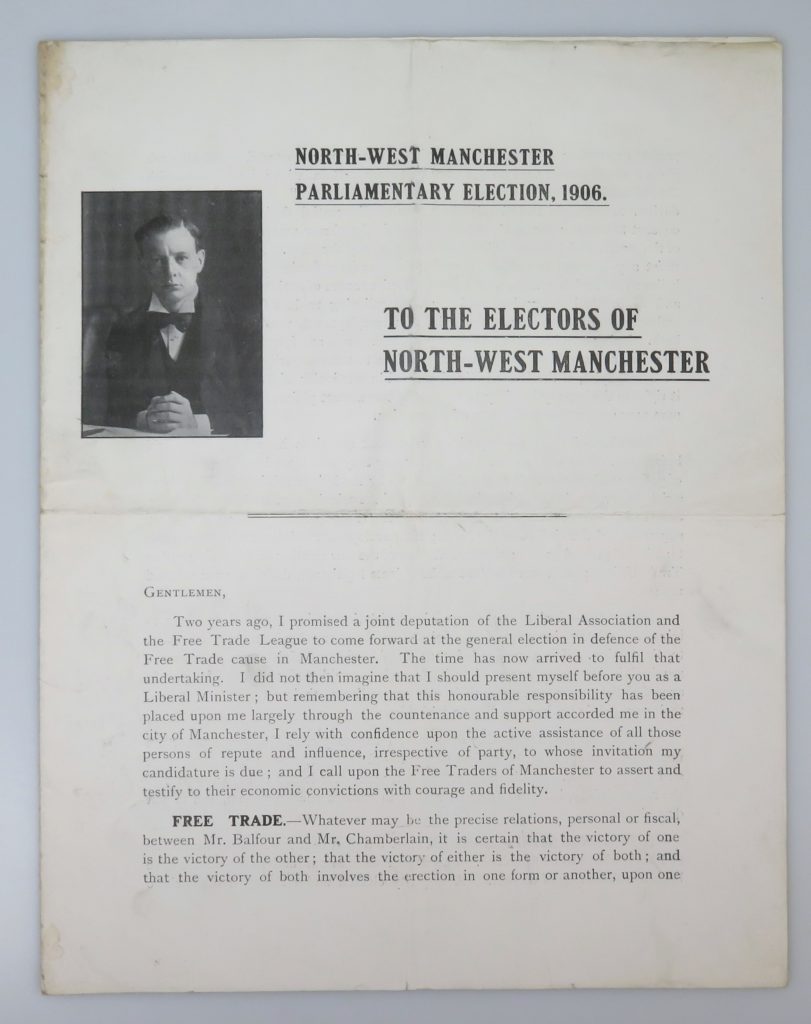

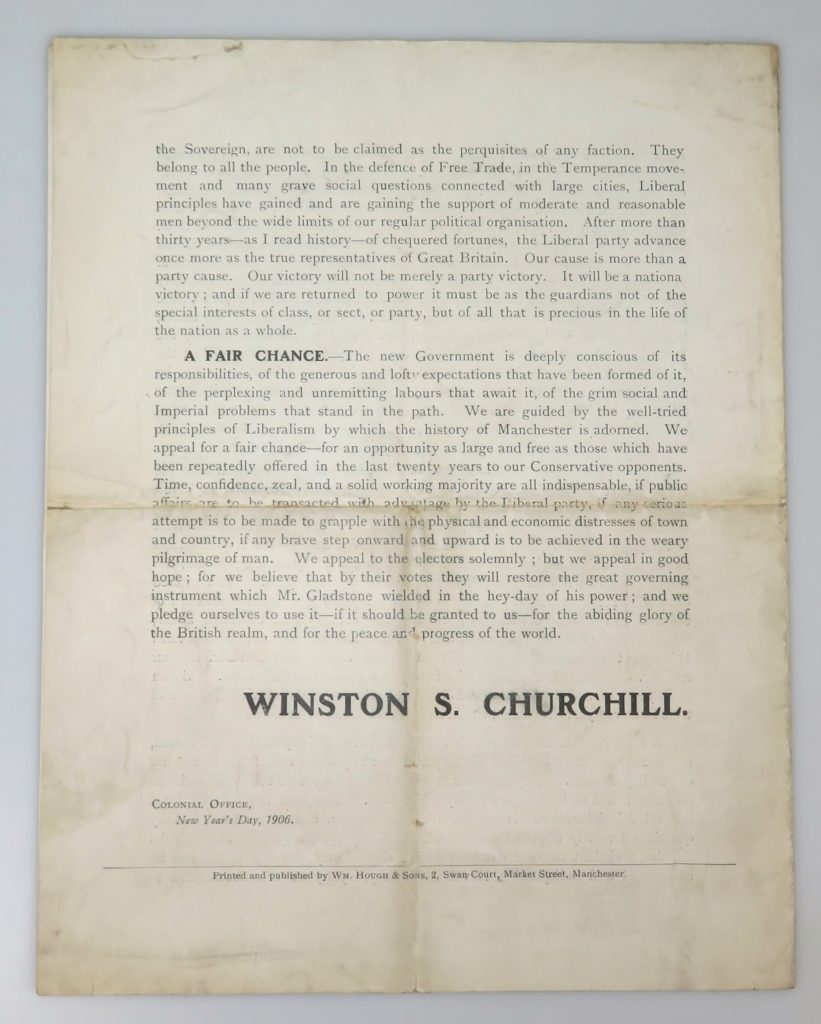

The leaflet consists of a single sheet folded once vertically to form four panels. The upper left of the front panel features the same iconic image of a stern and earnest young Churchill later featured on the dust jacket for Liberalism and the Social Problem (1909) and the wraps edition of The People’s Rights (1910). To the right of Churchill’s image is the statement “NORTH-WEST MANCHESTER | PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION, 1906.” and the titular “TO THE ELECTORS OF NORTH-WEST MANCHESTER”. Churchill’s address, with bolded sub-headings, fills the lower half of the front panel, two inner panels, and two-thirds of the rear panel, terminating in his printed name and “Colonial Office, New Year’s Day, 1906.”

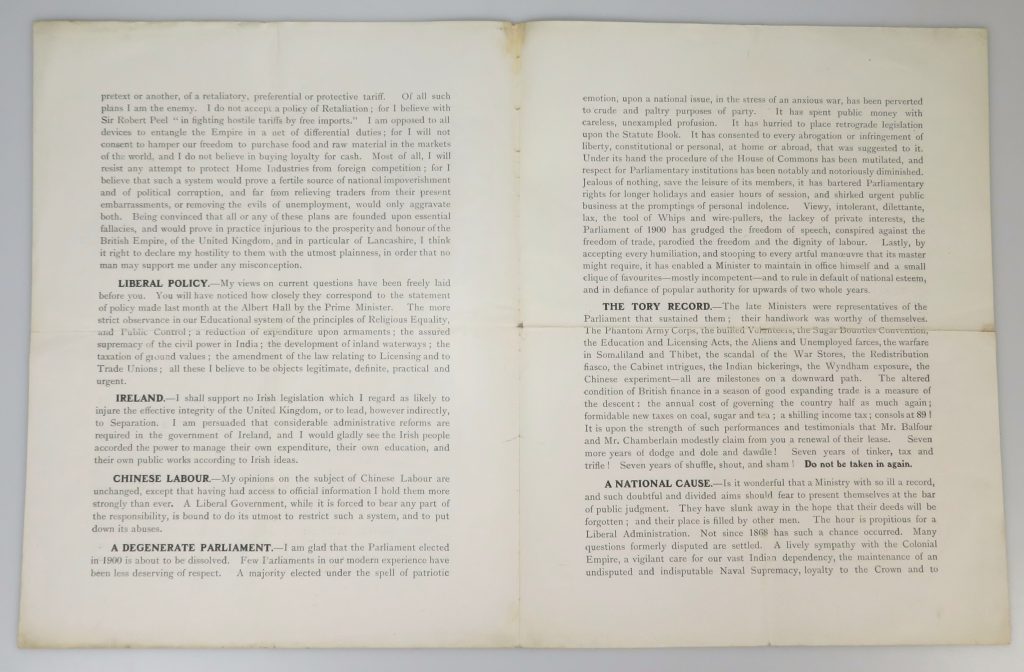

It was a distinctly pointed political document, full of the vehemence of a strident, confident young Churchill, hyperbolic on the hustings: “Few Parliaments in our modern experience have been less deserving of respect… It has spent public money with careless, unexampled profusion. It has hurried to place retrograde legislaton upon the Statute Book. It has consented to every abrogation or infringement of liberty, constitutional or personal, at home or abroad, that was suggested to it. Under its hand the procedure of the House of Commons has been mutilated, and respect for Parliamentary institutions has been notably and notoriously diminished. Jealous of nothing save the leisure of its members, it has bartered Parliamentary rights for longer holidays and easier hours of session, and shirked urgent public business at the promptings of personal indolence… grudged the freedom of speech, conspired against the freedom of trade, parodied the freedom and the dignity of labour… enabled a Minister to maintain in office himself and a small clique of favourites – mostly incompetent – and to rule in default of national esteem and in defiance of popular authority for upwards of two whole years… It is wonderful that a Ministry with so ill a record, and such doubtful and divided aims should fear to present themselves at the bar of public judgment.”

The bold subheadings encapsulate many of the issues that led Churchill to cross the aisle – among them “Free Trade”, “Liberal Policy”, “A Degenerate Parliament”, “The Tory Record”, and “A Fair Chance”.

Manchester had been a Conservative Party stronghold for nearly fifty years. Nonetheless, on 13 January 1906 Churchill, at the age of 31, won the traditionally Conservative seat with 5,639 votes out of a total of 10,037 votes cast with 89 percent of the electorate voting. “His efforts… helped… other Liberal candidates to overturn Conservative seats” in what became a Liberal landslide.

Churchill’s Address was published the same day in The Times and the Manchester Guardian, but this is the only stand-alone publication.

This conspicuously political leaflet and canvassing leaf is a tangible reminder of the bare-knuckle electoral underpinnings of a life spent in politics. Churchill’s political career would last nearly two thirds of a century, see him occupy Cabinet office during each of the first six decades of the twentieth century, carry him twice to the premiership and, further still, into the annals of history as a preeminent statesman. All of that depended on the support of the voters that he needed to place and keep him in office, and who he was already learning to cultivate in this 116-year-old piece of political ephemera that has – remarkably -both survived and made its way to us.

Cheers!