So I just co-authored a book about a letter. The experience was about as much fun as I’ve ever had as a lifelong bibliophile.

Among the oddities of life as a rare bookseller is that handling scarce and precious items can become a routine occurrence. But no matter how seasoned and jaded the bookseller becomes, there are still experiences that can invoke the giddy collector within.

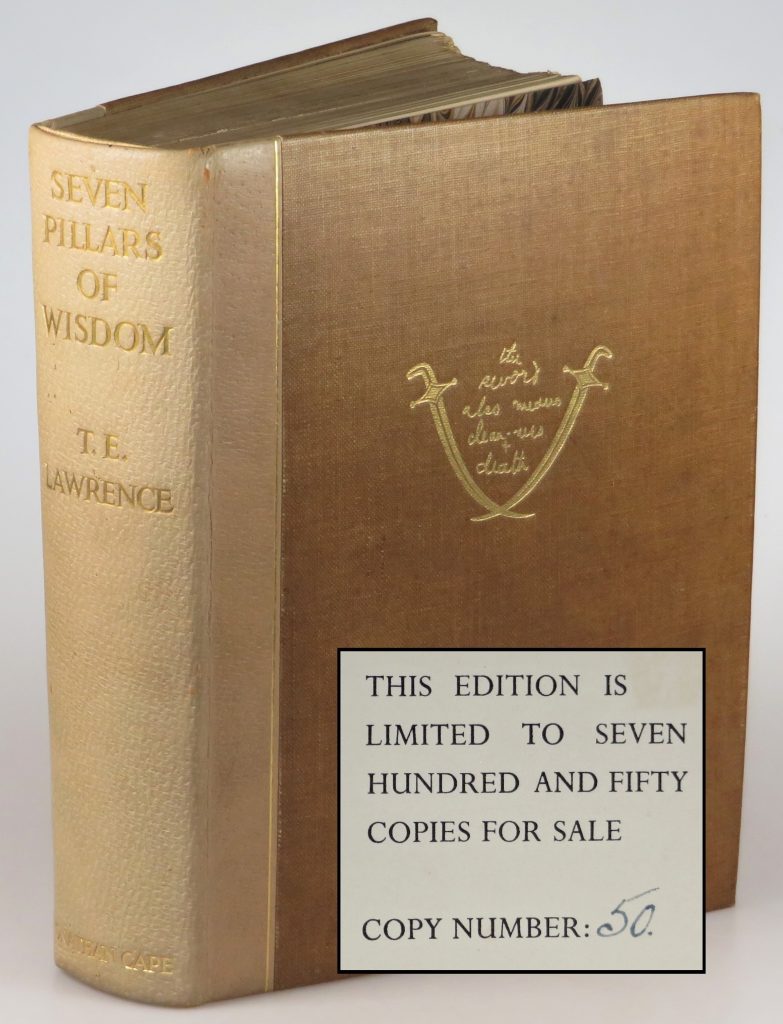

In 2018, we acquired a copy of the 1935 British limited issue of Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T. E. Lawrence, better known to the world as Lawrence of Arabia.

It’s a handsome and desirable book. In the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, the text of the 1926 Subscribers’ Edition was finally published for circulation to the general public in the form of a British first trade edition. Simultaneous with the first trade edition, the British publisher Jonathan Cape issued a finely bound, hand-numbered limited edition of 750 copies. This limited issue was bound in quarter tan pigskin over brown buckram boards with gilt stamped spine, gilt front cover illustration, and gilt rule transitions. The text is printed on untrimmed sheets with gilt top edge and bound with decorative headbands and marbled endpapers. It’s a handsome book, nice copies are reasonably scarce, and this is a fairly nice copy. Moreover, it is number 50, so early in the run.

But this story is not about the book. It’s about what we found in the book.

Our book arrived in the mail and was routinely opened by my assistant. Elise is smart, capable, diligent, and seldom misses an important detail about a book. I should have responded attentively when she called to me in the library and said “Hey, doesn’t this look like Lawrence’s handwriting?” Instead, I confess that I was initially dismissive.

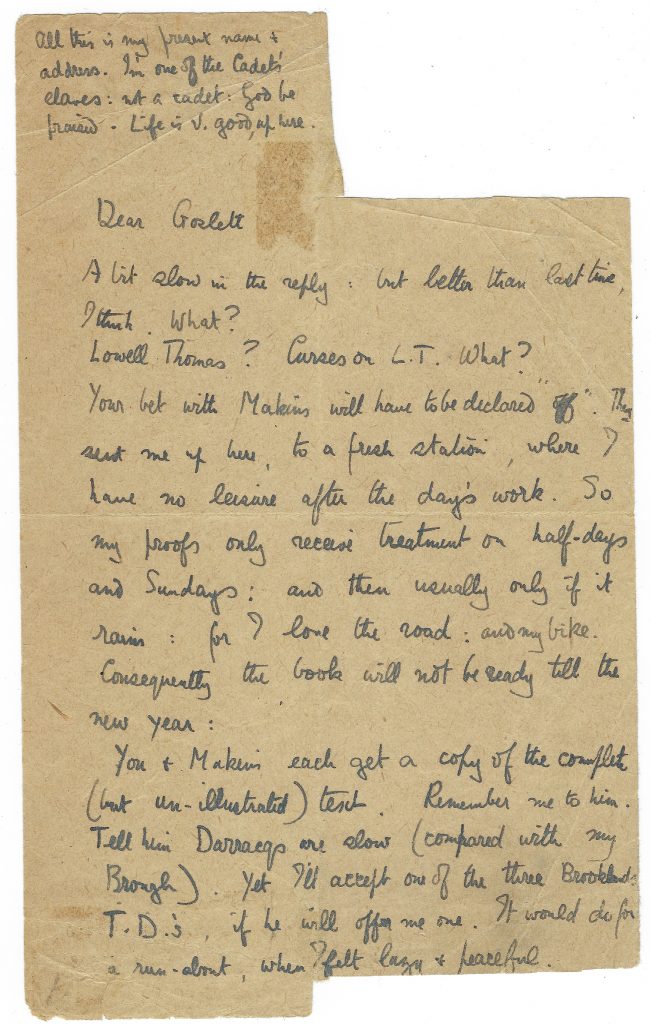

Actually, I was a bit of an ass. Picture classic bookseller pose. I turned to look at Elise, theatrically lowered my reading glasses, and told her that the publisher included facsimile reproduction of Lawrence’s handwritten notes in the book. Elise’s response – a deserved look of huffy condescension – got me off my high horse and over to her desk, where I found a letter, apparently entirely in Lawrence’s hand, tipped onto the book’s limitation page verso.

No kidding. Turns out that the jaded bookseller’s heart still goes pitter-patter.

A remarkable First World War odyssey as instigator, organizer, hero, and tragic figure of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire transformed Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) from an eccentric junior intelligence officer into “Lawrence of Arabia”. This indelible experience and celebrity, which he spent the rest of his short life struggling to reconcile and reject, to recount and repress, became Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

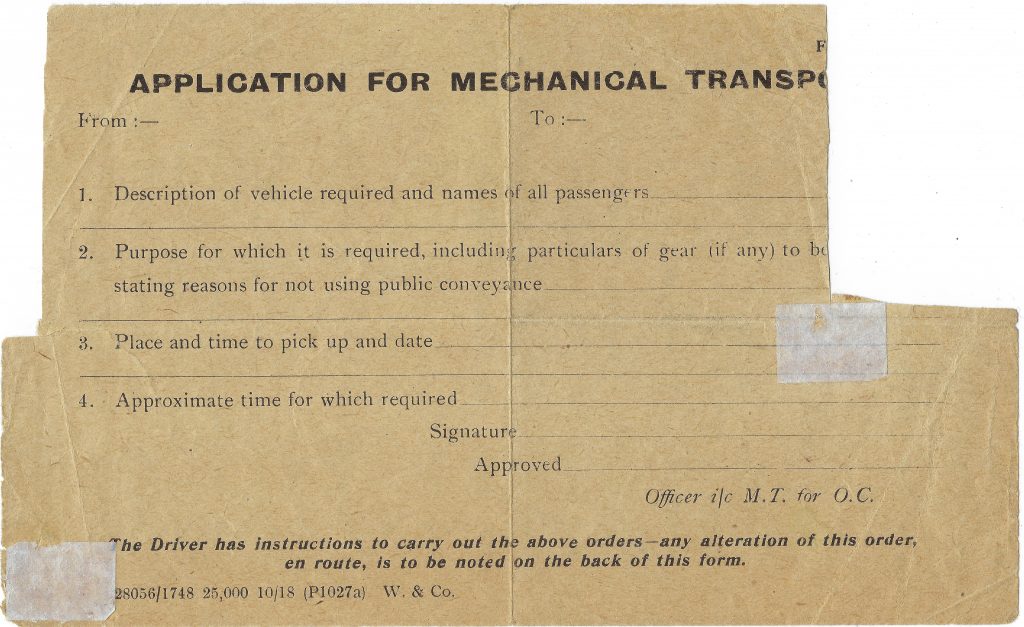

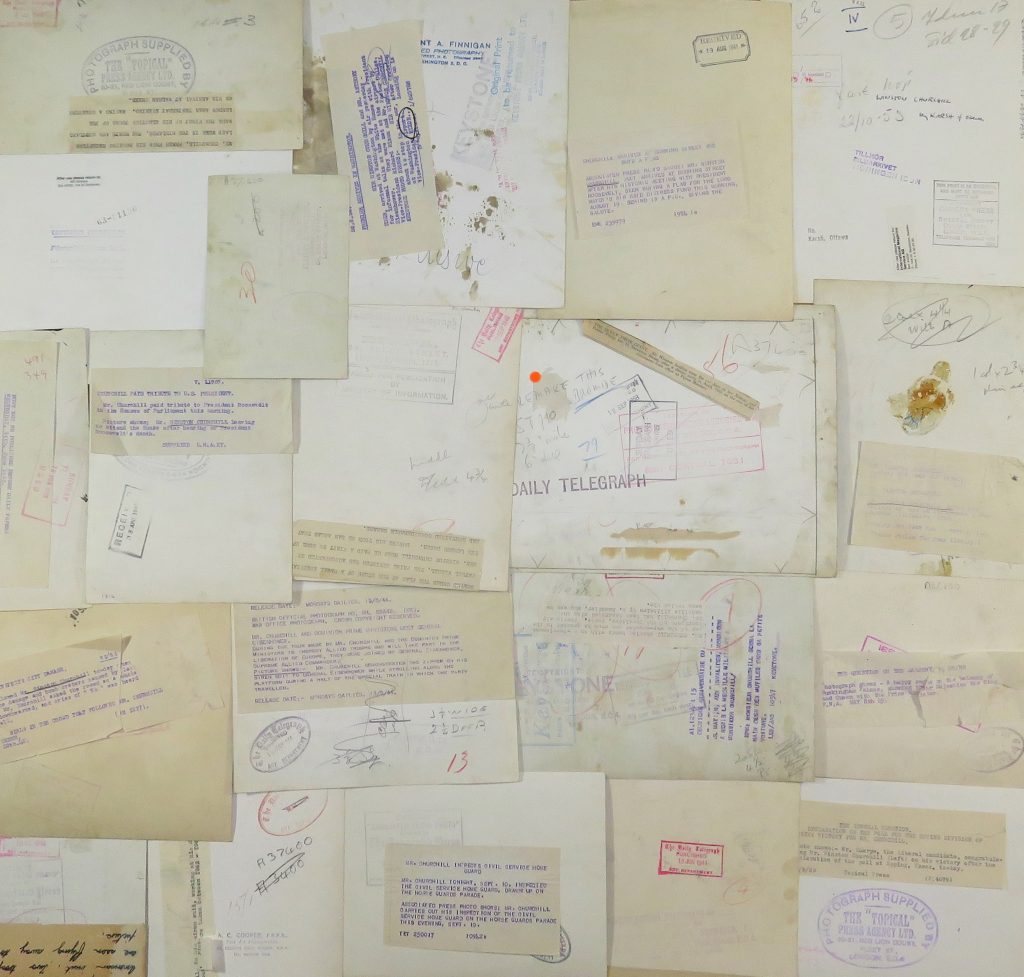

His letter prompted my own personal T. E. Lawrence odyssey. First, we reached out to a few experts – among them Nicole Wilson, co-founder of Castle Hill Press and widow of Lawrence’s official biographer, as well as Richard Knowles of Rickaro Books, a bookseller colleague who is an accomplished Lawrence collector, purveyor, and author. They, among others, validated our confidence that the letter was indeed written by Lawrence. Then we identified an appropriate conservator to carefully remove the letter from the book to which it had been adhered at two points. That led to a whole new round of excitement, as it turns out the letter had been penned on the back of an RAF “Application for Mechanical Transport”.

Lawrence’s correspondence has been painstakingly documented, much of it published by Lawrence’s official Biographer, Jeremy Wilson, and his wife, Nicole, of Castle Hill Press. Nonetheless, it turns out that nobody in the Lawrence community had ever seen or heard of this particular letter.

Once we ticked the authentication and conservation boxes, it was time for research. That proved a proverbial rabbit hole, as we sought to identify the time and context in which the letter was written and some of the more ambiguous references therein. This was, of course made more challenging by the fact that both the upper right corner of the letter, ostensibly bearing a date, and the signature at the lower right, had been excised – plausibly owing to the fact that even as early as the late 1920s, Lawrence’s signature already commanded considerable monetary value.

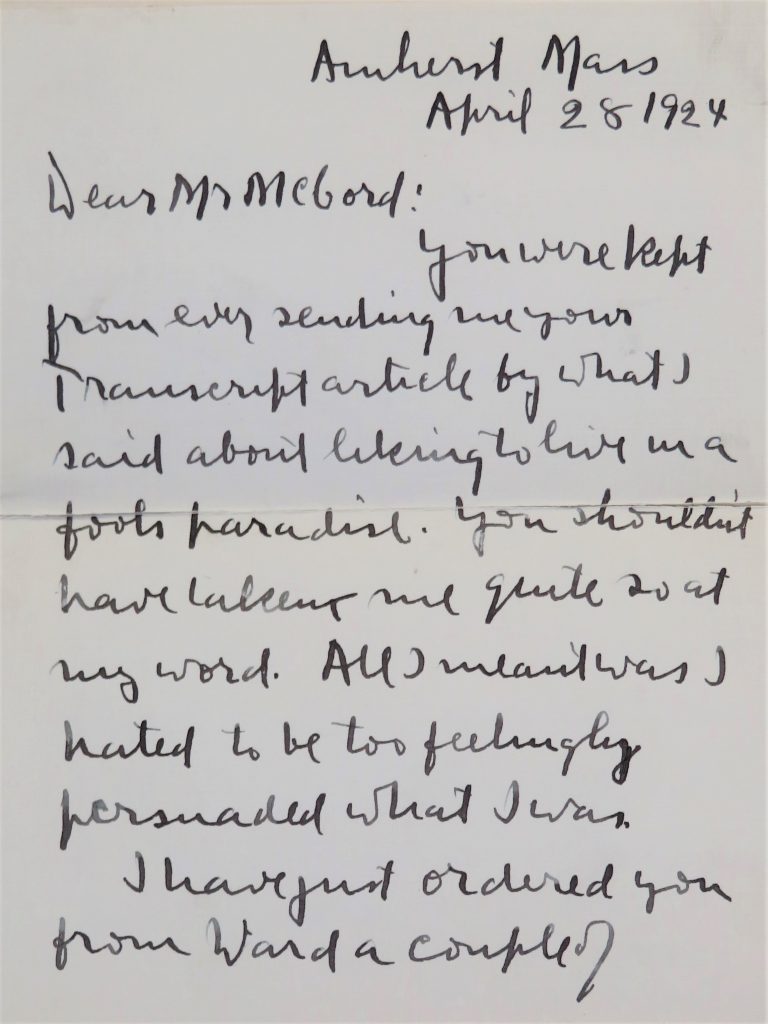

Here’s what the letter says:

Four lines at the upper right read: “All this is my present name & | address. I’m one of the Cadets’ | slaves: not a cadet: God be | praised. Life is v. good, up here.” The body of the letter reads: “Dear Goslett | A bit slow in the reply: but better than last time, | I think. What? | Lowell Thomas? Curses on L.T. What? | Your bet with Makins will have to be declared “off”. They | sent me up here, to a fresh station, where I | have no leisure after the day’s work. So | my proofs only receive treatment on half-days | and Sundays: and then usually only if it | rains: for I love the road: and my bike. | Consequently the book will not be ready till the | new year: | You and Makins each get a copy of the complete | (but un-illustrated) text. Remember me to him. | Tell him Darracqs are slow (compared with my | Brough). Yet I’ll accept one of the three Brooklands | T.D.’s, if he will offer me one. It would do | for a run-about, when I felt lazy & peaceful.”

Though short, the letter is compelling. In just 164 words, Lawrence references many of the disparate, competing threads that skeined his life – complicated feelings about fame, attempted retreat to the comparative anonymity of the RAF, personal conflict about publication of his literary masterpiece, the famous 1926 subscribers’ edition, love of motorcycles, the sensibility for comradeship that made him, however reluctantly, a leader of men, and even a glimpse of the personal peace he always seemed to want but seldom seemed to find.

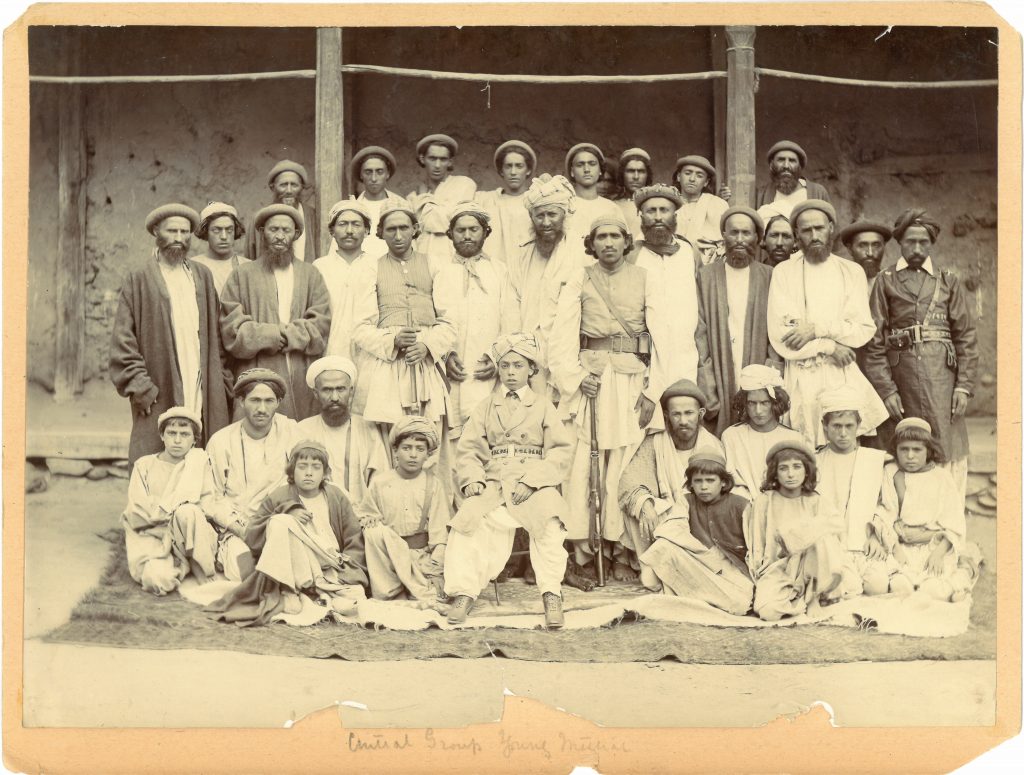

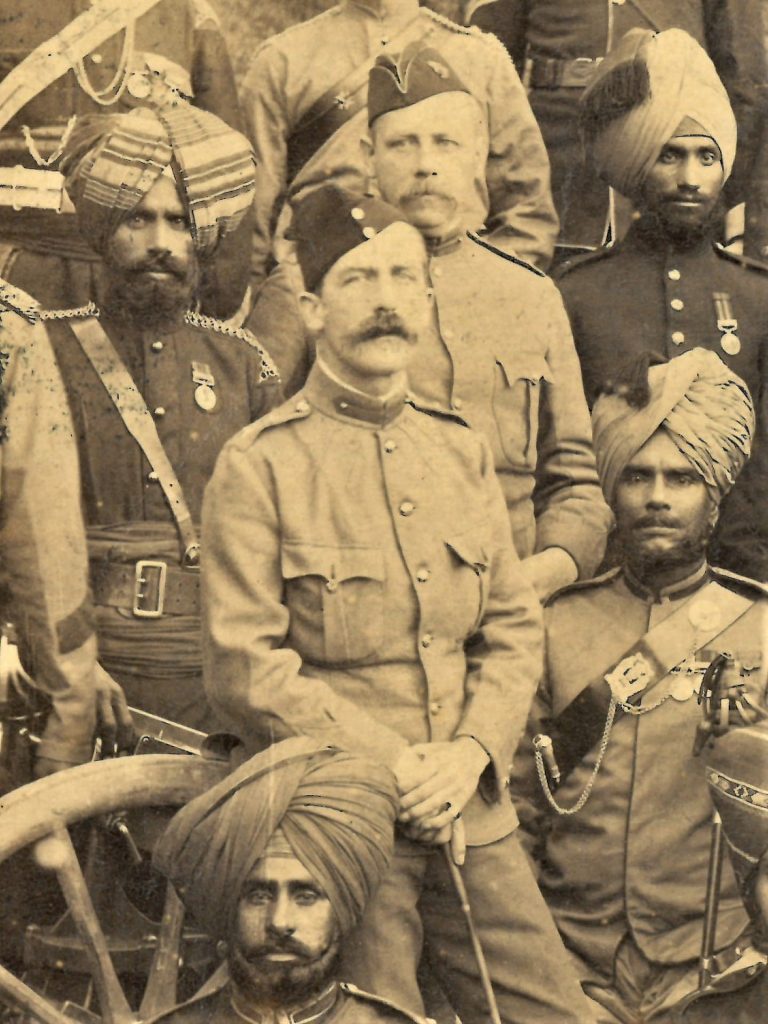

Eventually, we narrowed the date of the letter with reasonable certainty to between August 1925 and December 1925. It turns out that “Goslett” is Captain Raymond Goslett M.C. (1885-1961), “the supply wizard of Al Wajh and Al Aqabah,” a key figure in the Arab Revolt and wartime friend of Lawrence who inadvertently played a role in facilitating his fame. “Makins” is Arthur Dayer Makins, D.F.C., R.R.G.S., F.I.M.T. (1888-1974), a Royal Flying Corps flight lieutenant with X Flight in Arabia who after the war was associated with the motor trade. Lawrence cited both men in his acknowledgements for the 1926 subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars and each was gifted a copy. To the American radio commentator, lecturer, author, and journalist Lowell Jackson Thomas (1892-1981), who Lawrence “Curses”, Lawrence owed the discomfort of both his fame and famous sobriquet.

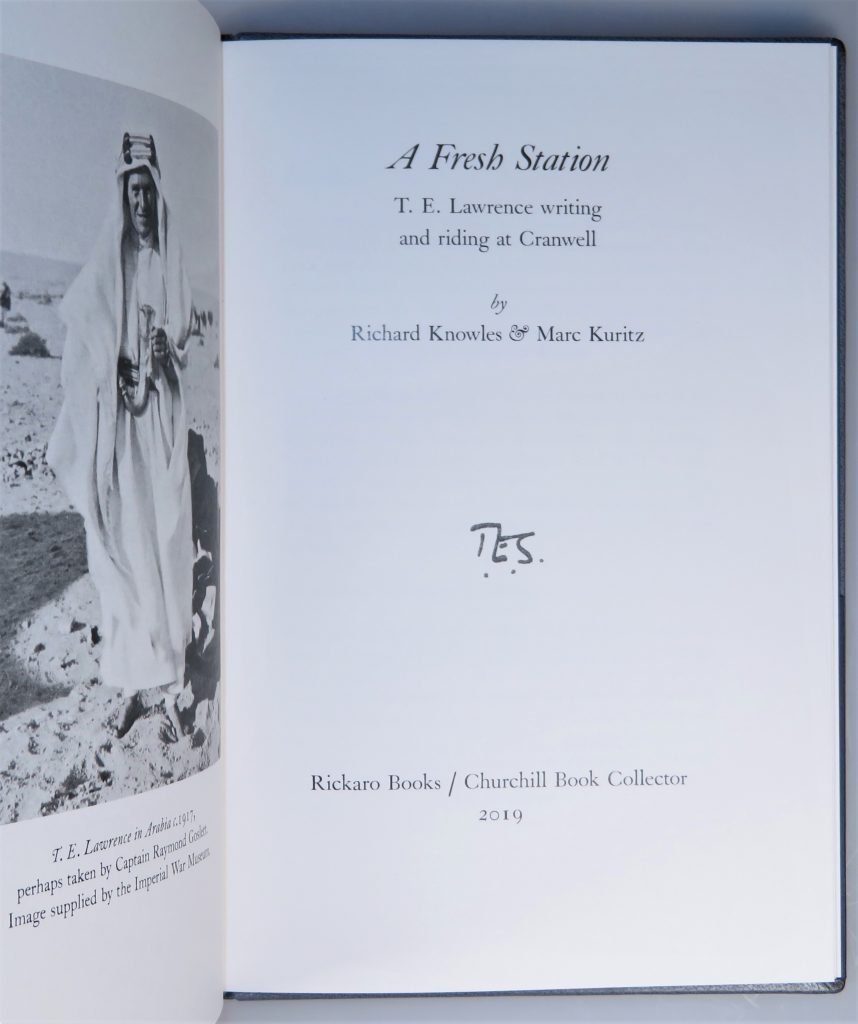

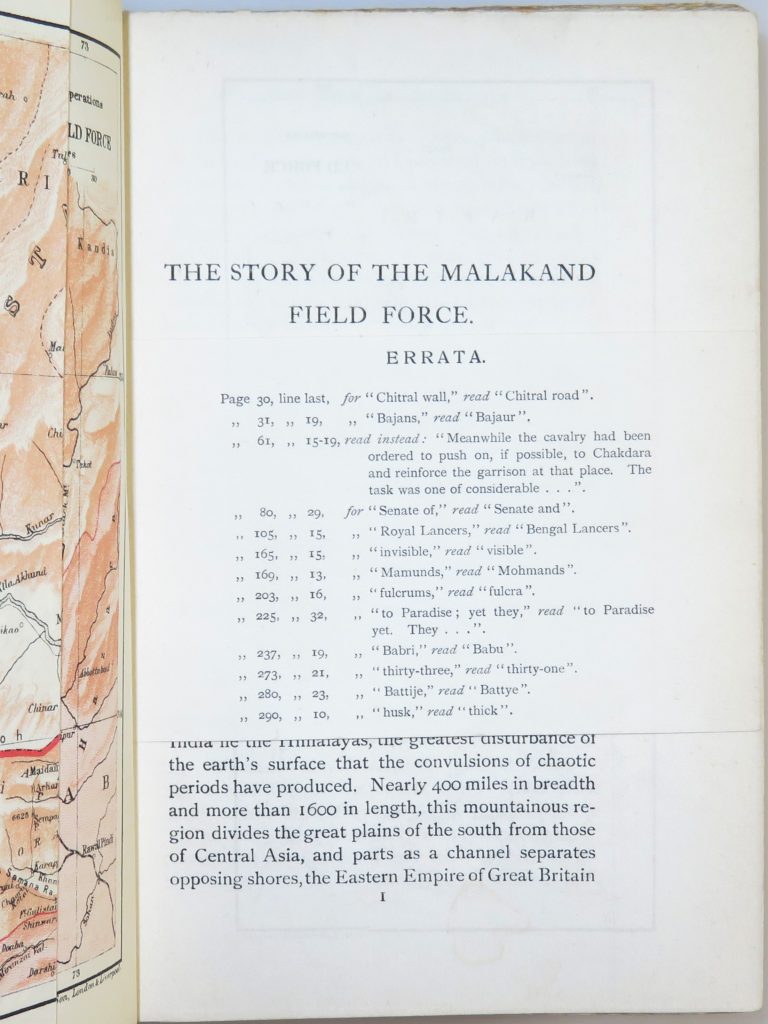

Note that I keep saying “we”. The aforementioned Richard Knowles, proprietor of Rickaro Books, shared my enthusiasm. As research and contextualization unfolded this long-lost little letter, we decided it merited an essay. This in turn became an illustrated book, which we titled “A Fresh Station”, taking the title from Lawrence’s own reference to the RAF Cadet College at Cranwell – “…a fresh station, where I have no leisure after the day’s work.” Lawrence was posted to Cranwell in August 1925 and where he completed the famous 1926 “subscribers’” or “Cranwell” edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. A Fresh Station sketches Lawrence’s life writing and riding at Cranwell specifically through the prism of this newly discovered letter.

Winston Churchill said of his friend, Lawrence:

“Lawrence had a full measure of the versatility of genius. He held one of those master keys which unlock the doors of many kinds of treasure-houses. He was a savant as well as a soldier. He was an archaeologist as well as a man of action. He was an accomplished scholar as well as an Arab partisan. He was a mechanic as well as a philosopher. His background of sombre experience and reflection only seemed to set forth more brightly the charm and gaiety of his companionship, and the generous majesty of his nature.”

These are just a few of the millions of insightful and eloquent words written both by and about Lawrence.

So why another Lawrence book?

It may be helpful to note that *after* he wrote the definitive and widely praised official biography of Lawrence and *after* he edited and published the most complete and definitive edition of Lawrence’s magnum opus, Jeremy Wilson took on the mammoth task of attempting to gather, cogently organize and contextualize, and systematically publish all of Lawrence’s correspondence. Jeremy was still working on this task when he died in 2017, nearly three decades after he published his biography of Lawrence.

I shouldn’t presume to speak for Jeremy, but I suspect that what may have helped drive his interest in and commitment to Lawrence’s correspondence is the fact that we still don’t know who Lawrence was. Not really. “TE” as he was known to friends, remains a remarkably enigmatic figure. We investigate his character and exploits though his published works – which span the WWI Arab revolt and life inside the inter-war RAF to crusader castles and ancient Greek translation to technical manuals on high speed boats – but it may be that Lawrence’s letters offer some of the clearest views. As this letter and the enfolding essay A Fresh Station suggest, the fragmentary candor and verities of Lawrence’s correspondence may best enable us to approach the animating spirit of this singular, complex, and multi-faceted person.

A Fresh Station is another small window on Lawrence, opened by the welcome discovery of a few more of his own words.

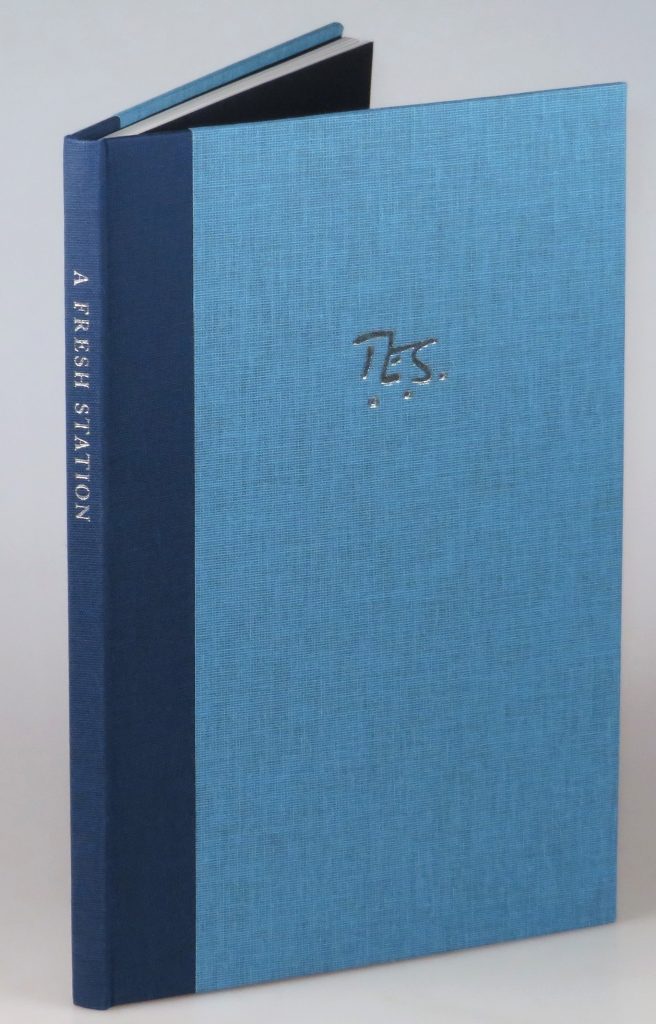

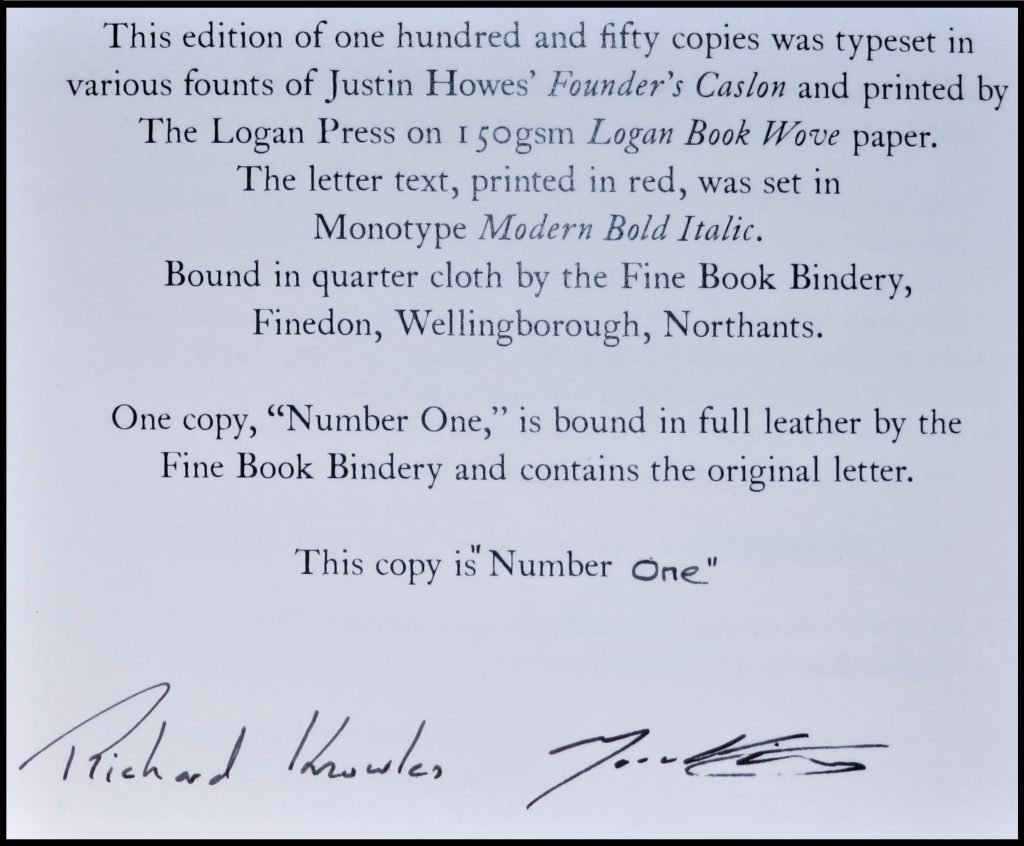

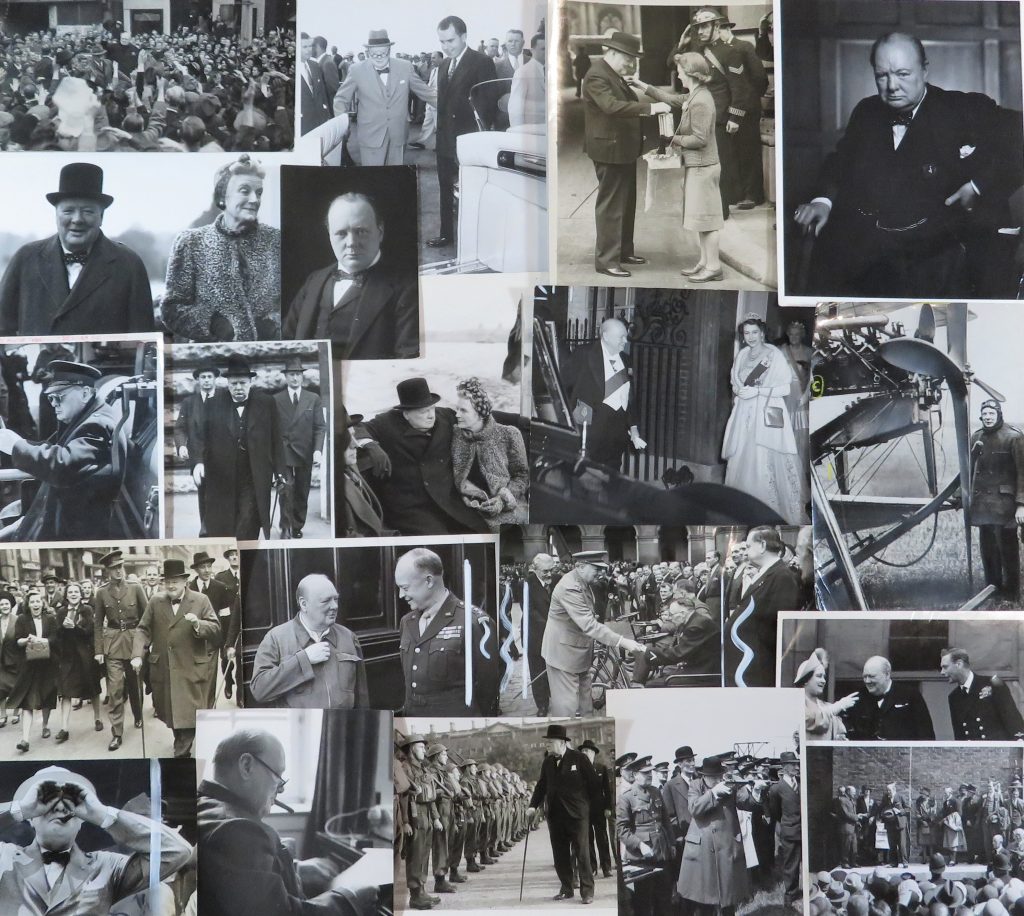

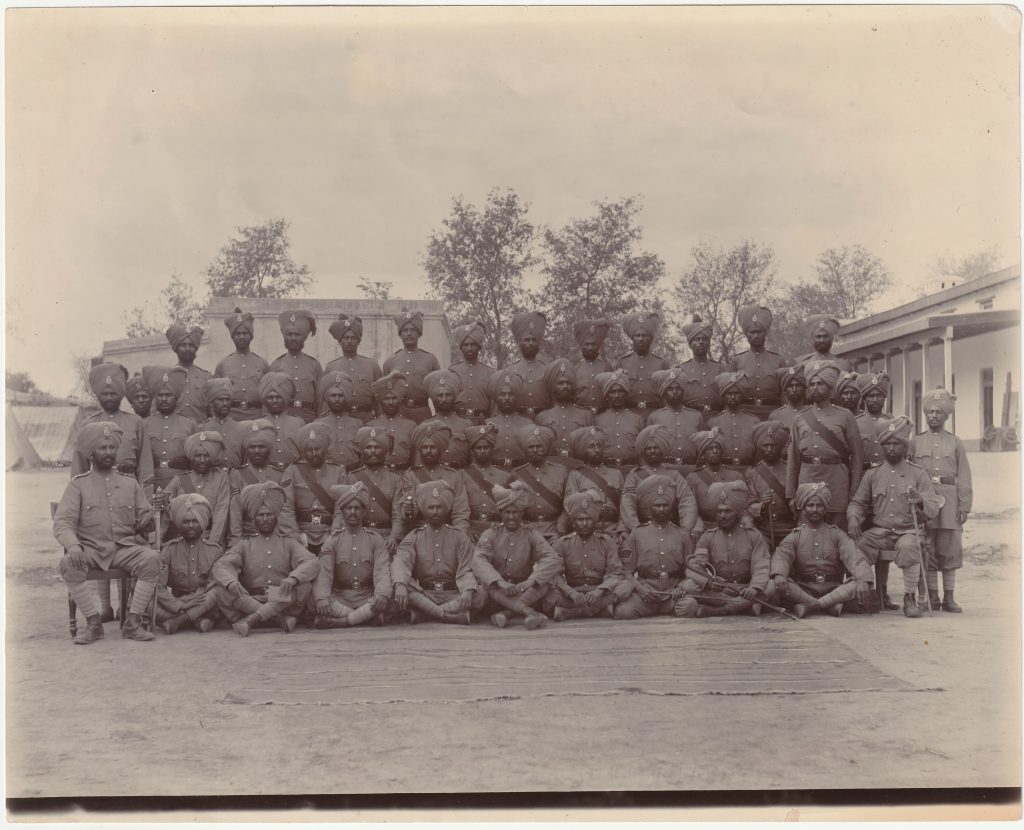

Of a limited edition of 150 hand-numbered copies of A Fresh Station, 149 are bound by the Fine Book Bindery in quarter cloth featuring navy spine and blue-grey boards evoking RAF colours, the spine printed in silver, the front cover bearing the initials Lawrence was wont to use at the time. The illustrated contents are printed by The Logan Press on 150 gm Logan Book Wove paper and include a full facsimile of Lawrence’s letter, as well as images of Lawrence, Goslett, and Makins.

These new, hand-numbered copies are offered exclusively HERE by Churchill Book Collector and HERE by Rickaro Books.

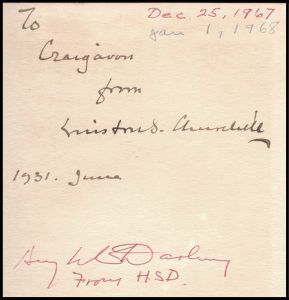

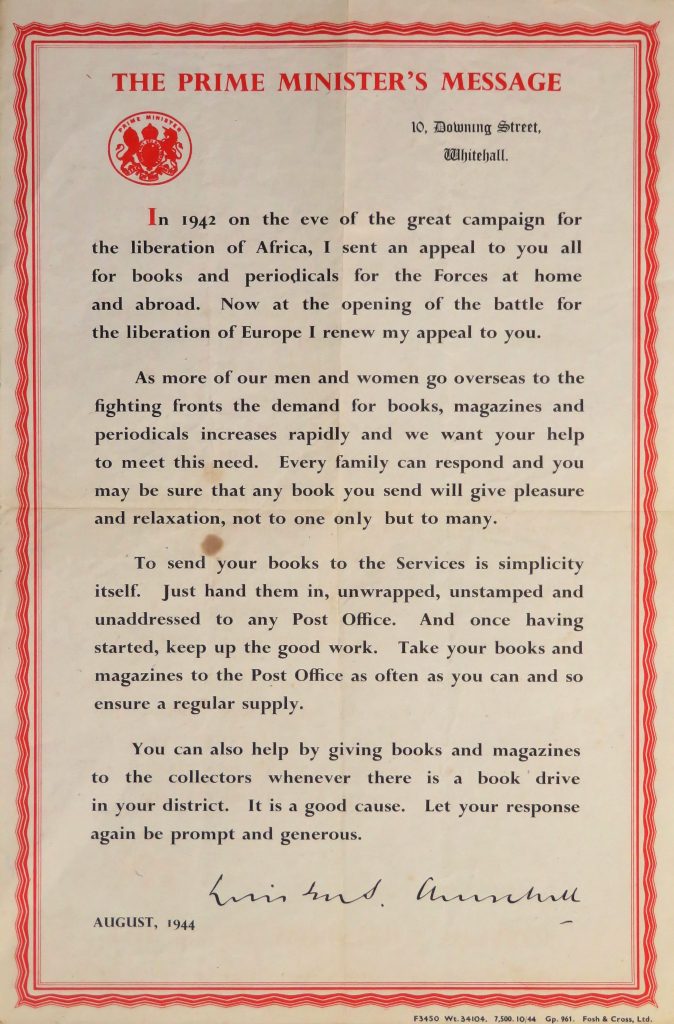

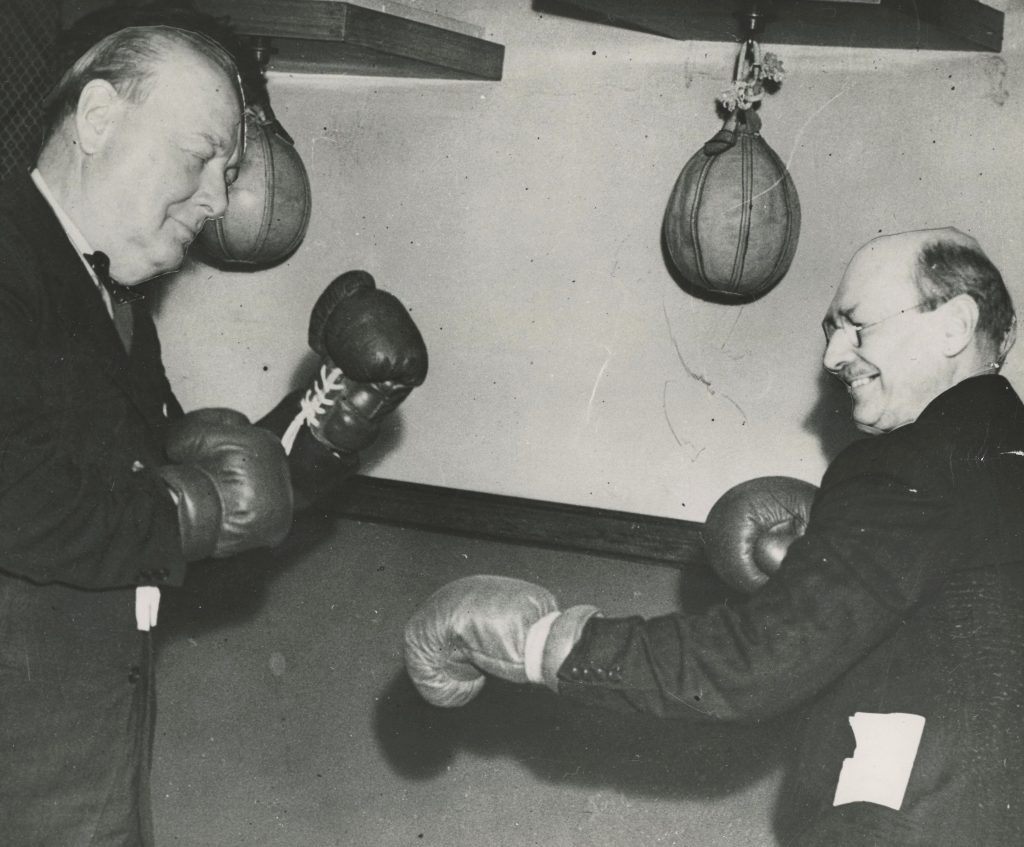

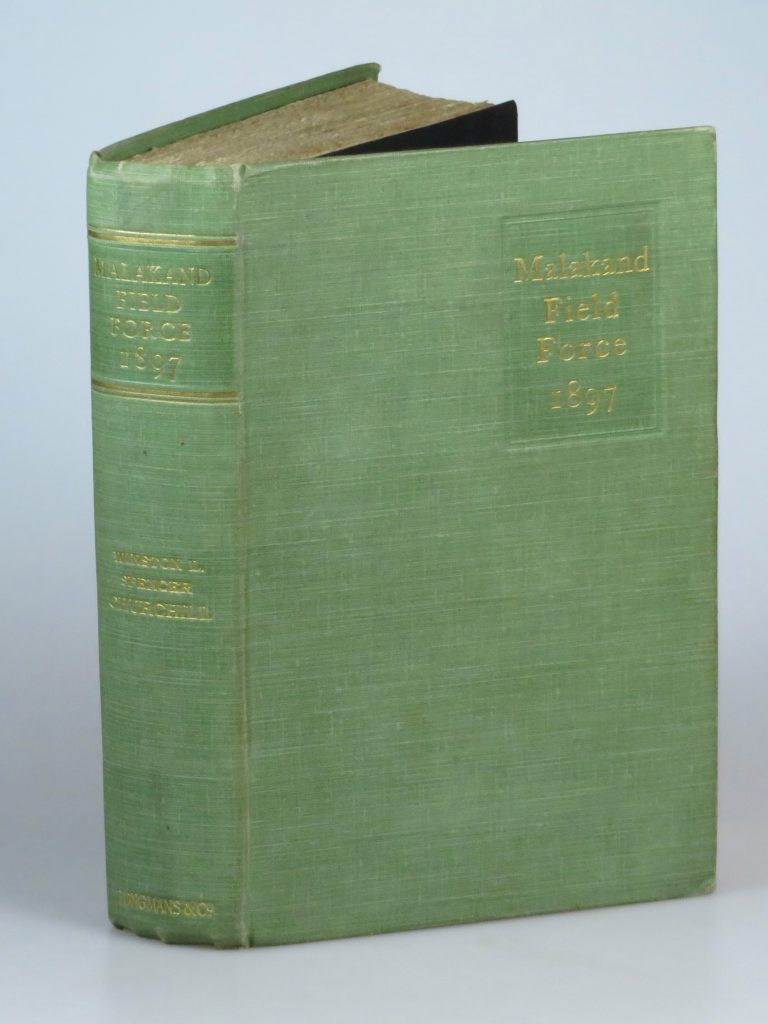

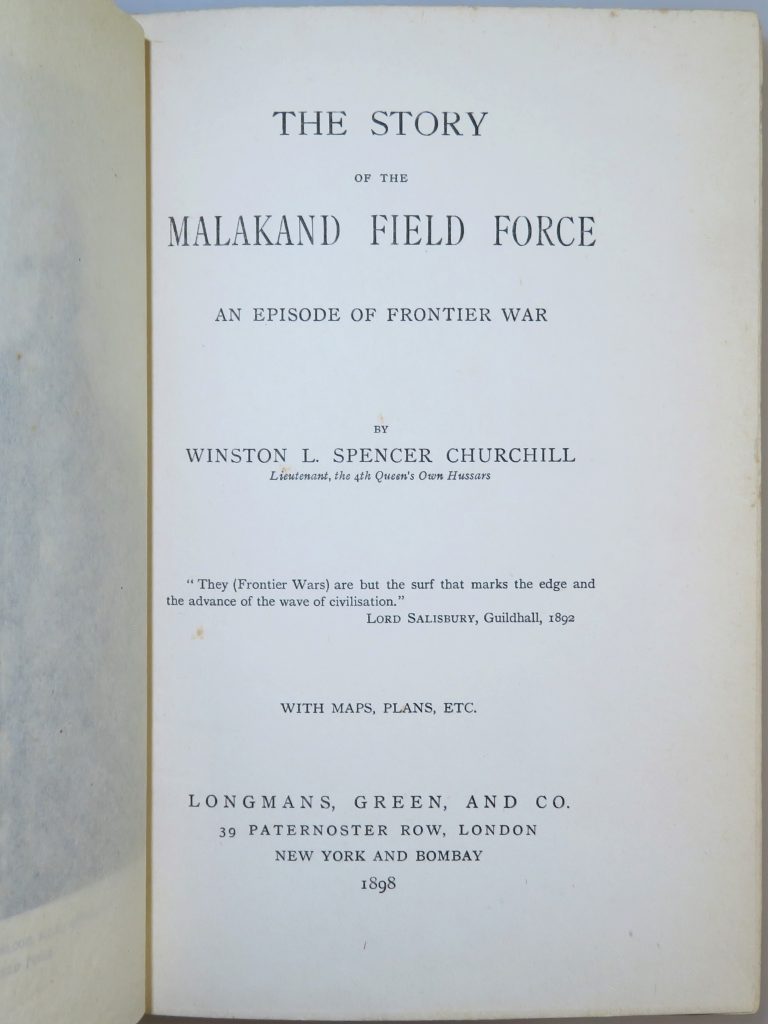

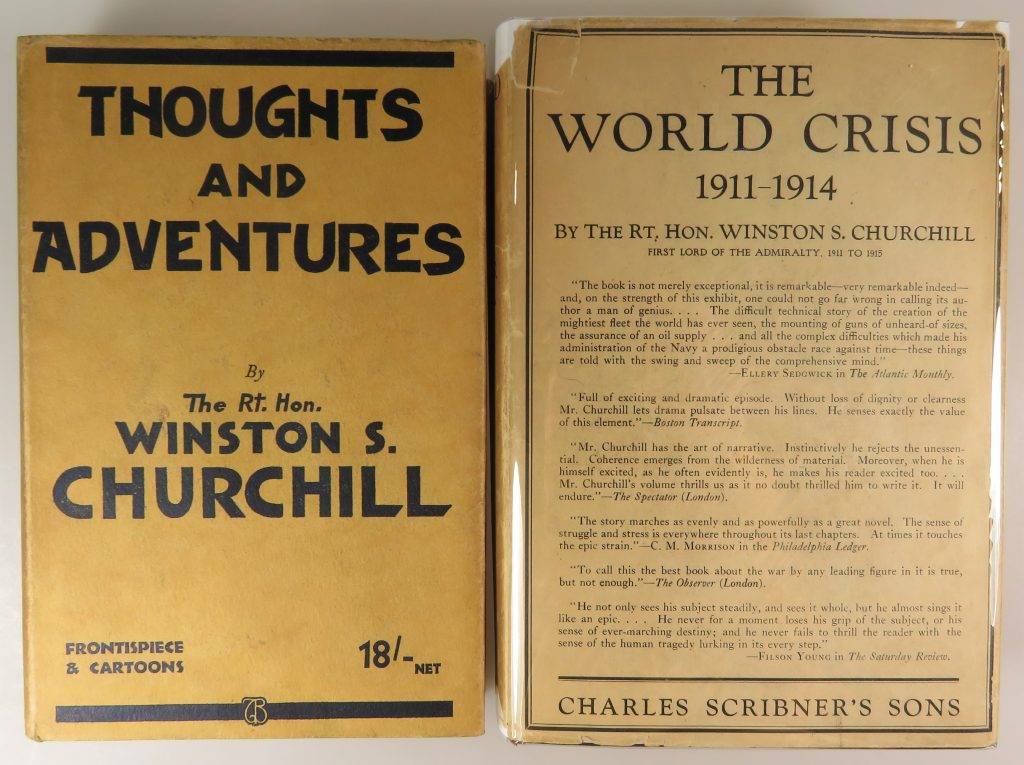

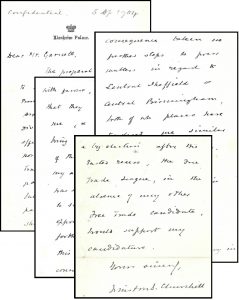

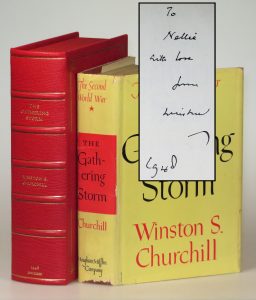

Copy “Number One”, signed by the authors, now houses and accompanies the original letter. “One” is specially bound by the Fine Book Bindery in blue-grey morocco (evoking the RAF) and housed in a custom cloth solander. This copy, the letter, and the accompanying copy “50” of the limited 1935 UK issue of Seven Pillars, in which this letter was found, will be offered for sale in our forthcoming print catalogue Six Degrees of Winston: Signed or inscribed books, ephemera, and correspondence by or about Winston S. Churchill, his contemporaries, and his time.

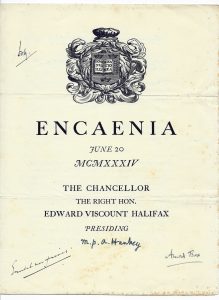

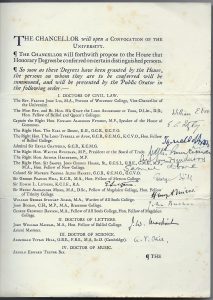

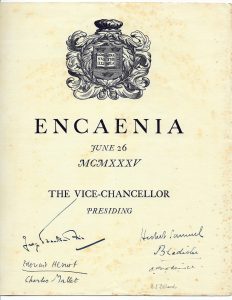

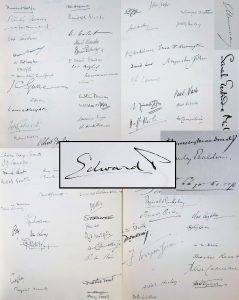

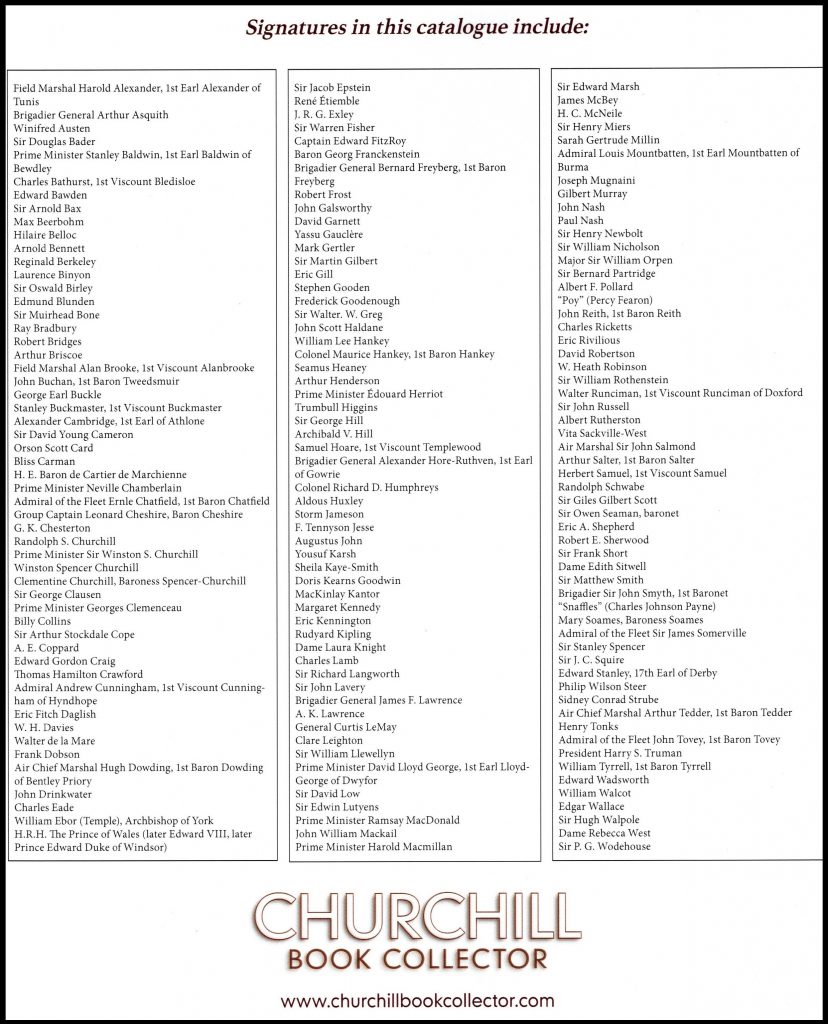

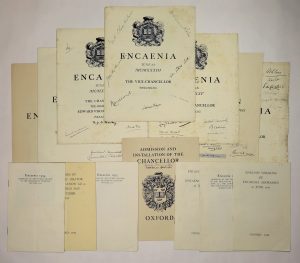

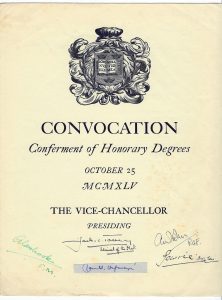

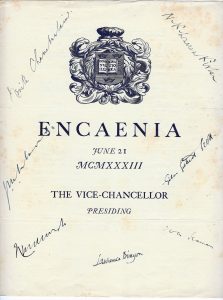

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth.

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth. These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures.

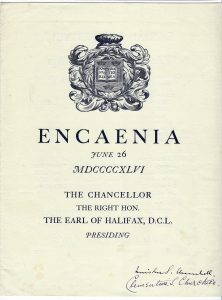

These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures. Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”.

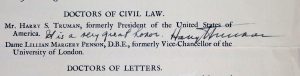

Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”. Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

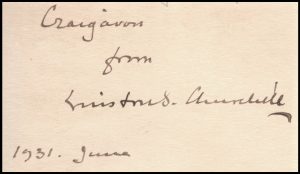

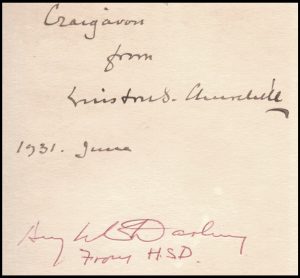

Encaenia, June 21, 1933

Encaenia, June 21, 1933