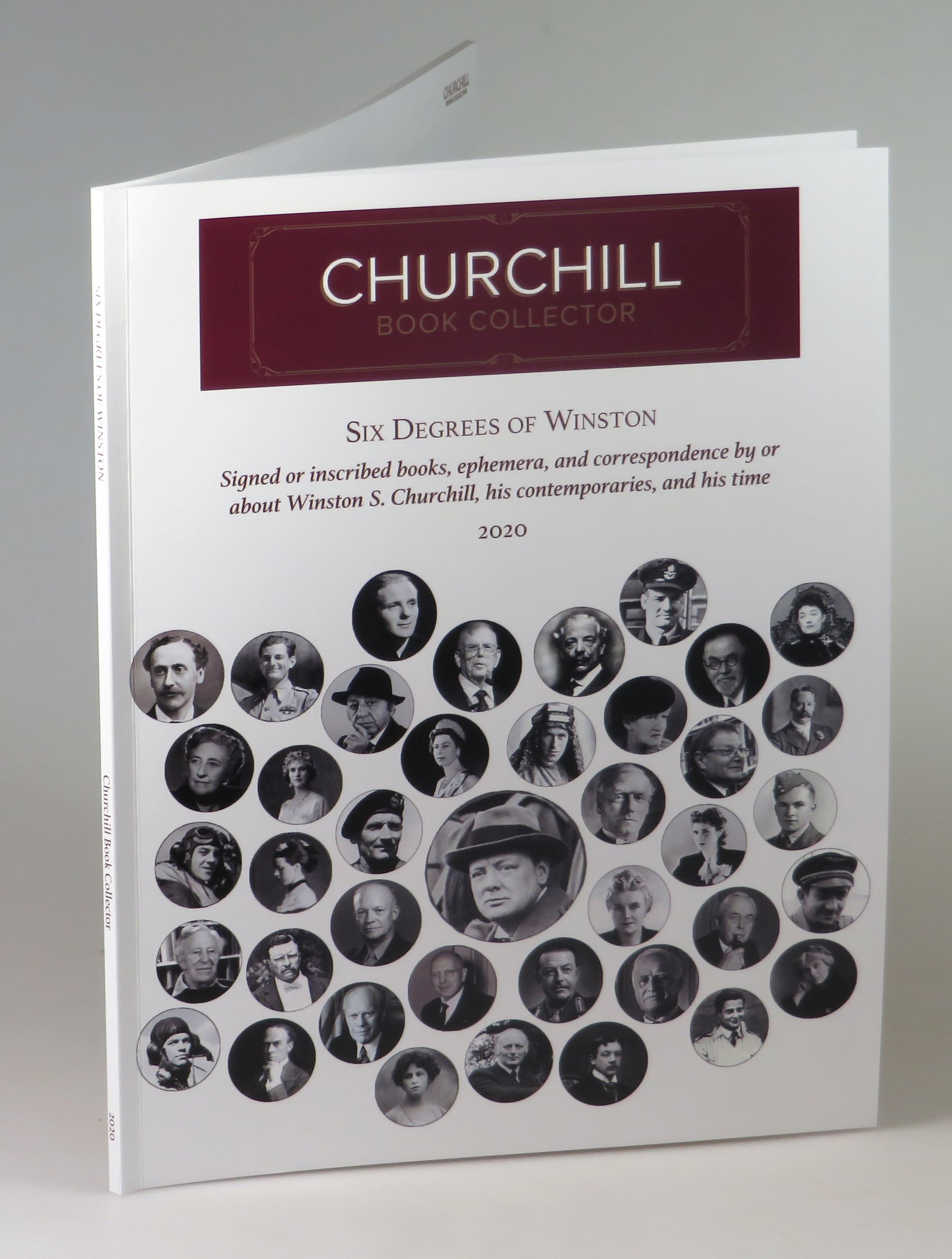

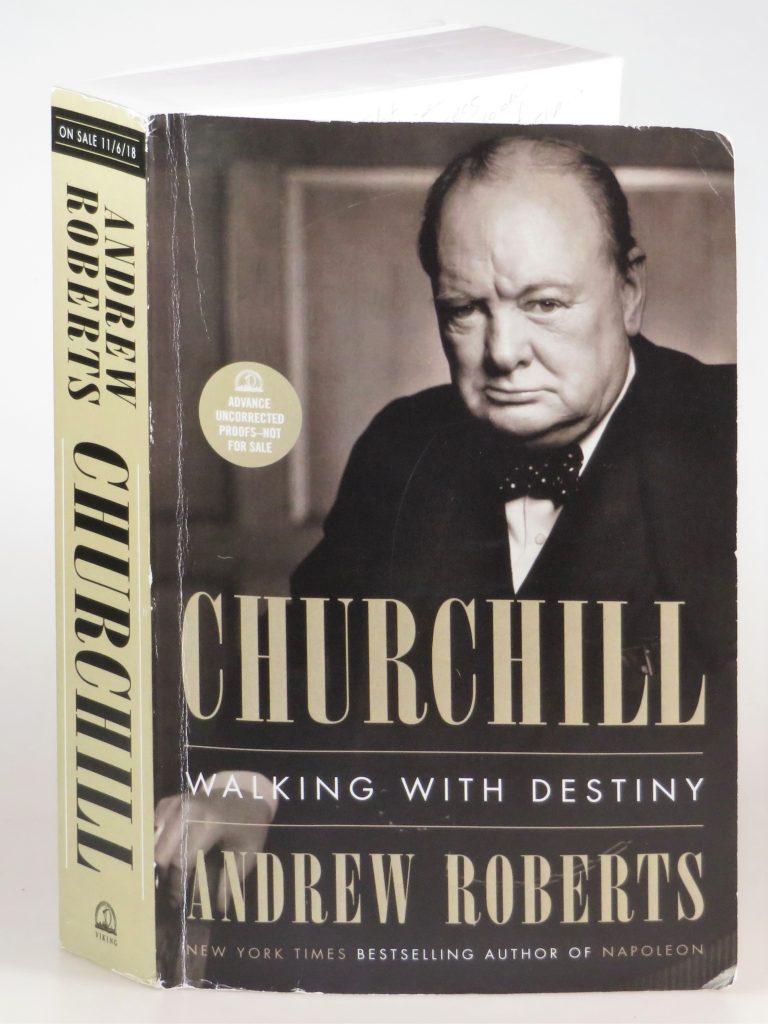

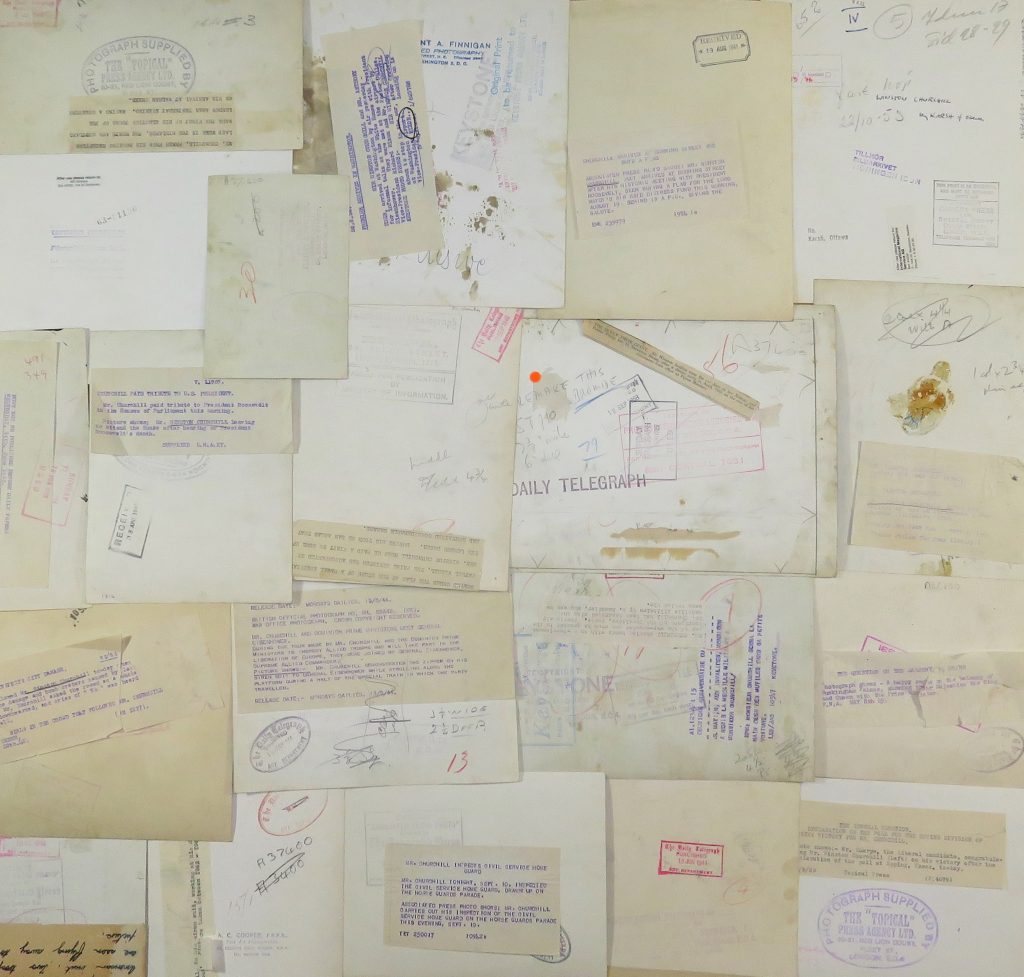

Valentine’s Day seems an appropriate occasion to rhapsodize about connectedness. So I’m writing to introduce Six Degrees of Winston – our new catalogue which includes signed or inscribed books, ephemera, and correspondence by or about Winston S. Churchill, his contemporaries, and his time.

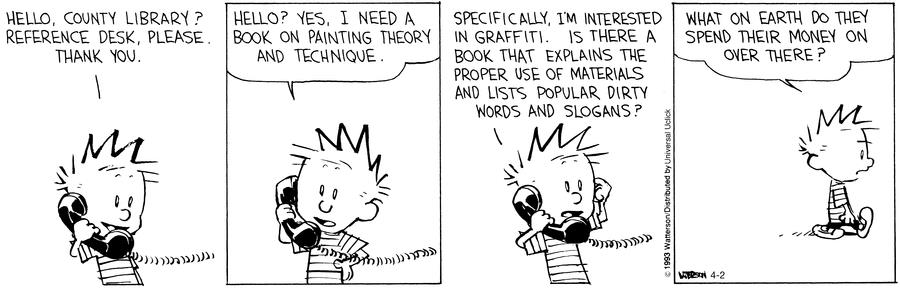

Of course, there’s some contrivance in the catalogue title; we like to keep it interesting, and merely titling a catalogue “Some more cool stuff you should buy” is not our style. That said, there’s a little more to the six degrees idea than mere marketing. Hence this post.

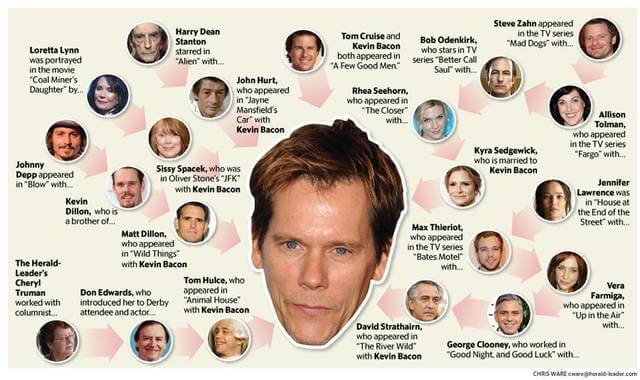

“Six degrees of separation” is the idea that any human being can be connected to any other human being through a chain of acquaintances with no more than five intermediaries. Frankly, it can seem hard to believe.

Skepticism seems warranted, particularly given that the idea is nearly a century old and originated as fiction. Conception of the phenomenon is attributed to a 1929 short story titled “Chains” by Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy. Despite origins in fiction, this notion that social distance disregards physical and social barriers, that an ever-swelling global population is still proximately interconnected, resonates in the zeitgeist.

Since 1929, a number of mathematicians, sociologists, and physicists have conducted various experiments more or less validating the idea. In the late 1960s, Stanley Milgram and Jeffrey Travers designed an experiment using the mail that tested and validated Karinthy’s idea, which they called the “small world” hypothesis. Others followed. And then came the Internet. Twenty-first century “six degrees” experiments conducted by the likes of Columbia University and Microsoft access the unprecedented data mine of electronic communication.

But we don’t have to rely on scientific experiment. For anti-vaxxers, climate change deniers, and others who poo-poo objective data, there’s a less methodical way to go about substantiating Karinthy’s notion – “Six degrees of Kevin Bacon”. That’s the parlor game where movie buffs challenge each other to find the shortest connection between any arbitrary actor and actor Kevin Bacon. For example – John Malkovich. He acted in Death of a Salesman with Dustin Hoffman who acted in Sleepers with Kevin Bacon. You get the idea.

The “six degrees” notion has proven not only persistently captivating, but also presciently persistent. The world’s population has roughly quadrupled since Karinthy’s story was published in 1929, but the addition of nearly six billion human beings has not appreciably increased the degrees by which we are separated.

Even as I type these words, engaging in the doubly archaic exercise of introducing a print catalogue intended to sell items of paper and ink, the cultural prairie fire of social media is – for better or for worse – validating the perceptive imagination of Frigyes Karinthy.

Which, of course, doesn’t tell you anything about what this has to do with Winston Churchill and our shiny new catalogue.

A number of “six degrees” inferences pertain.

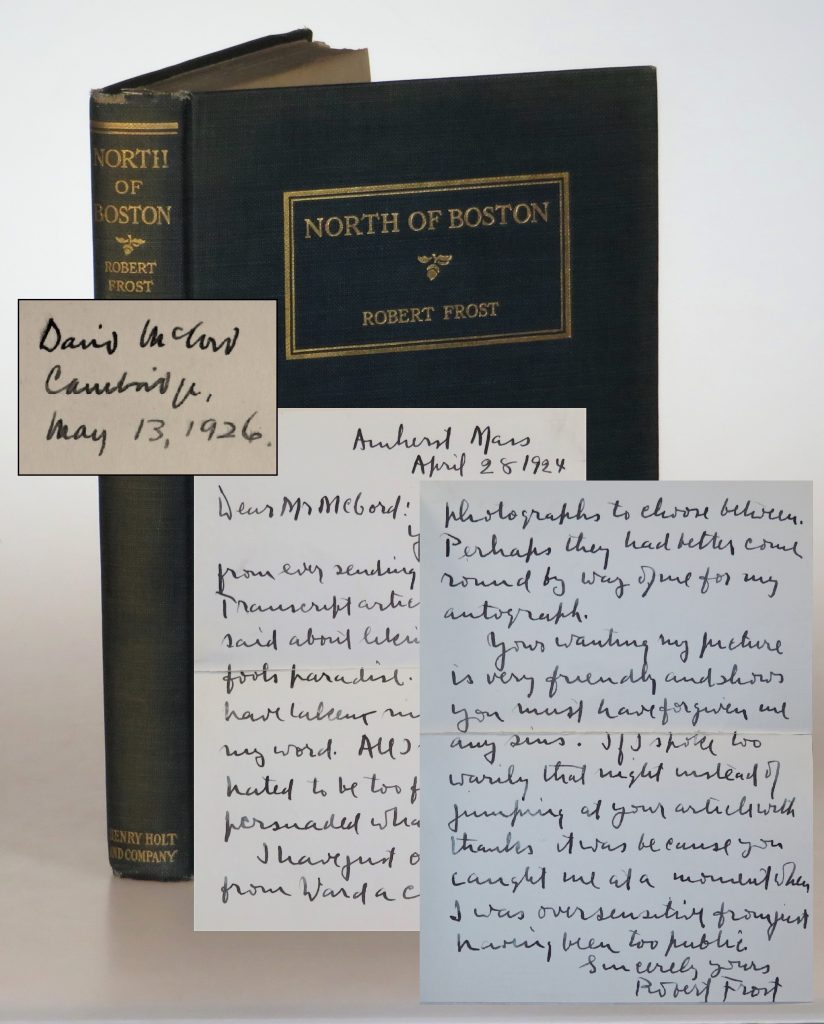

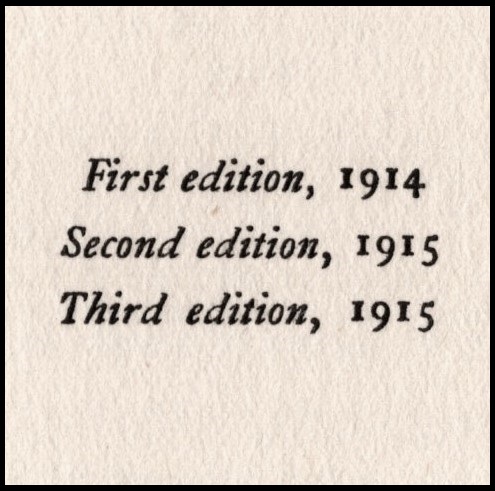

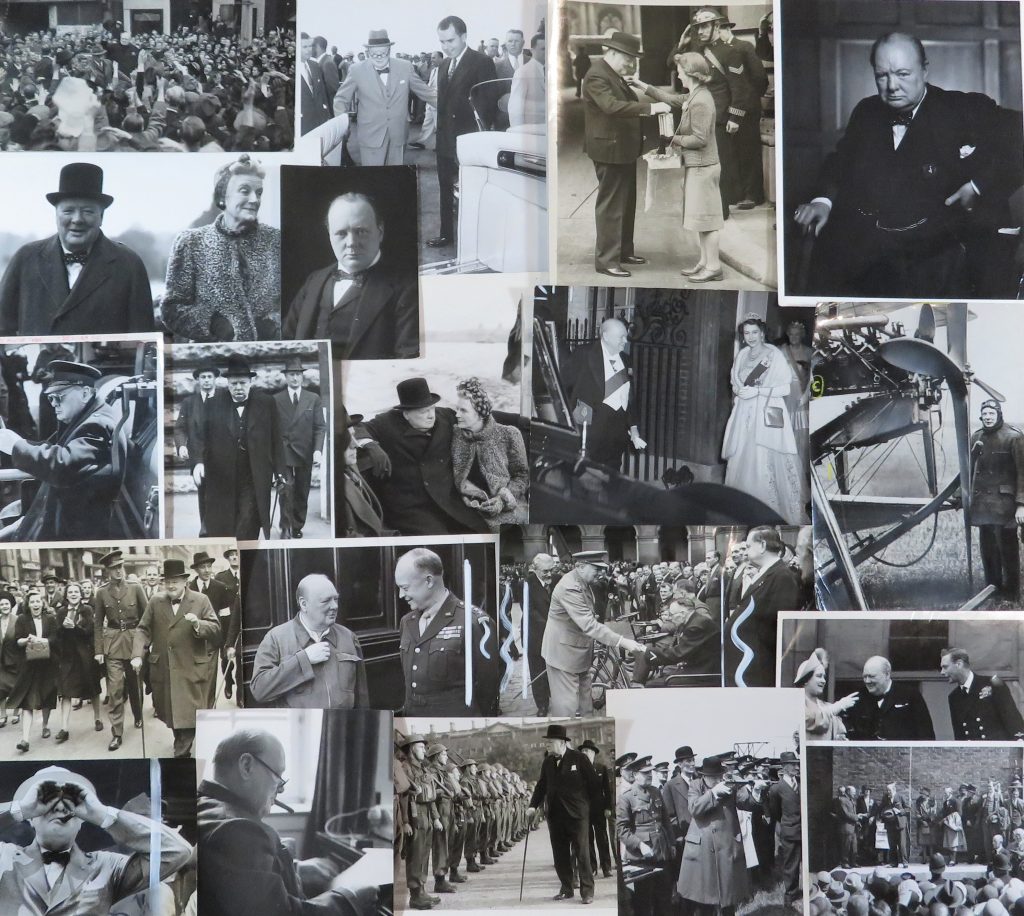

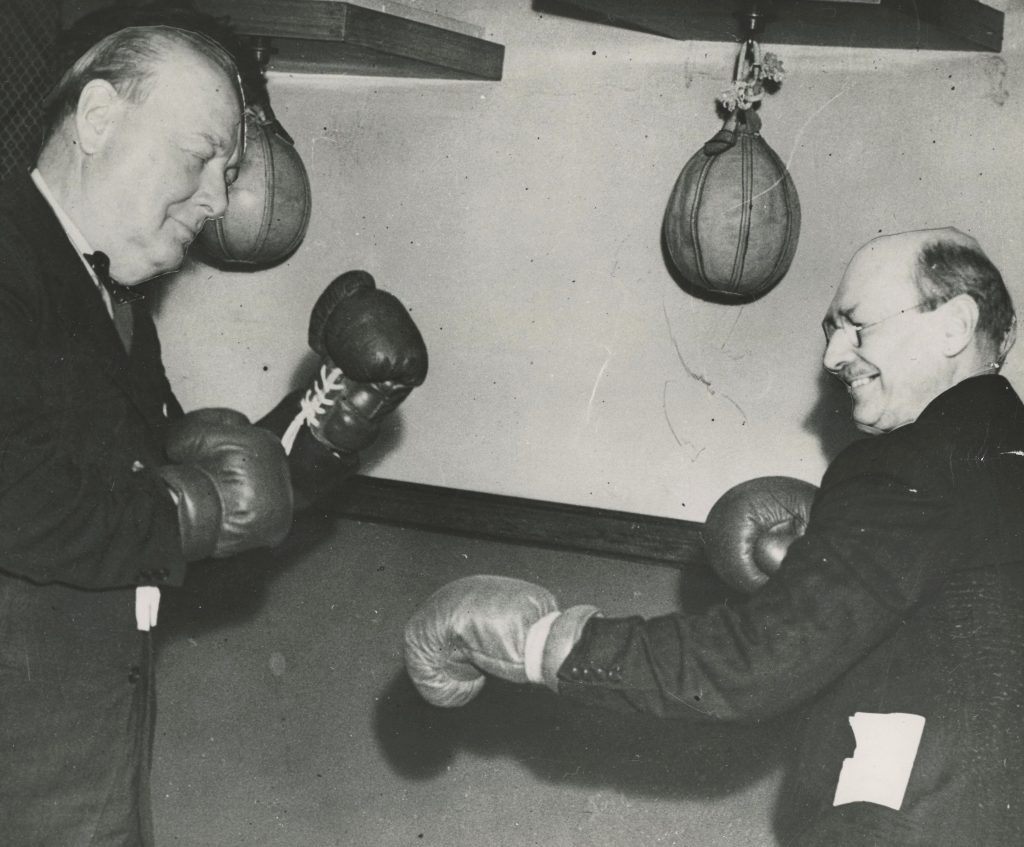

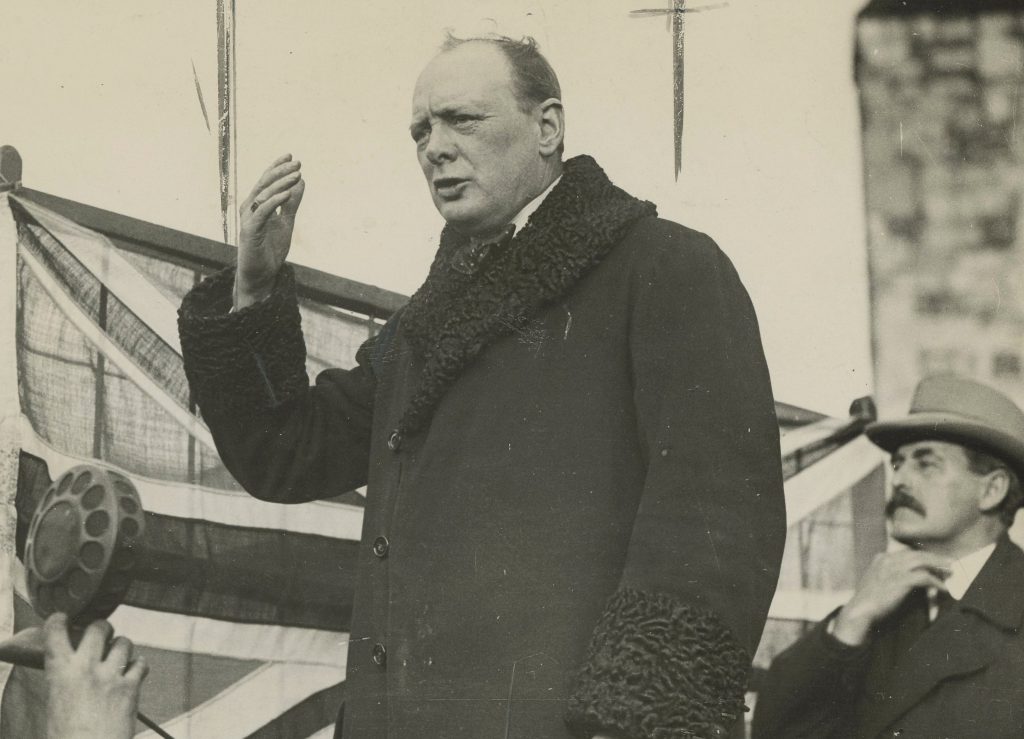

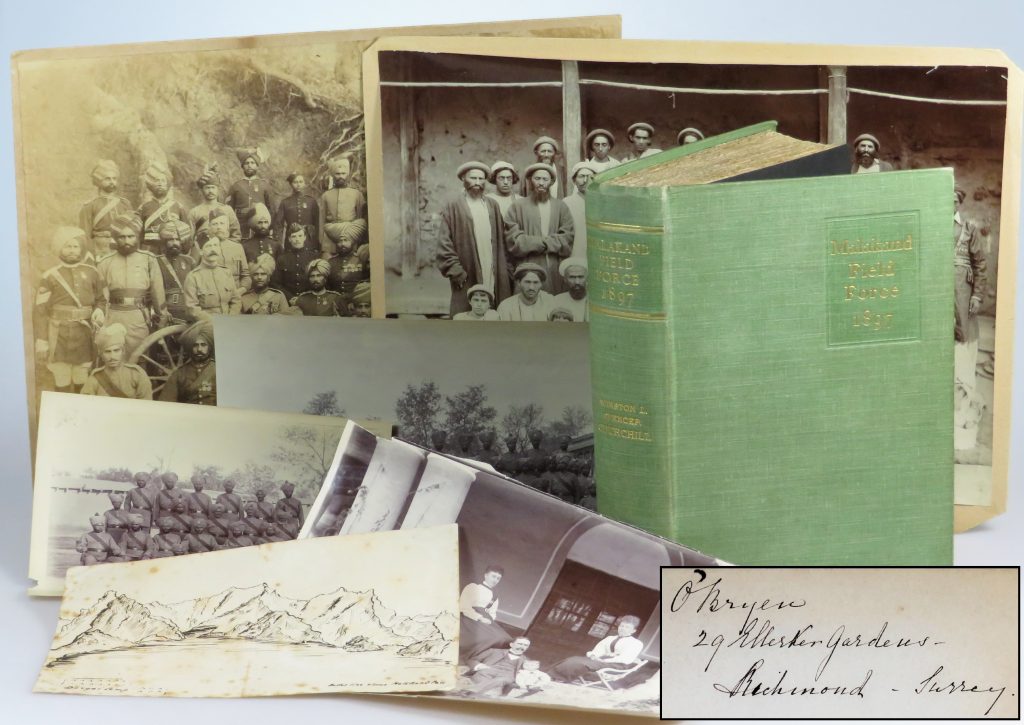

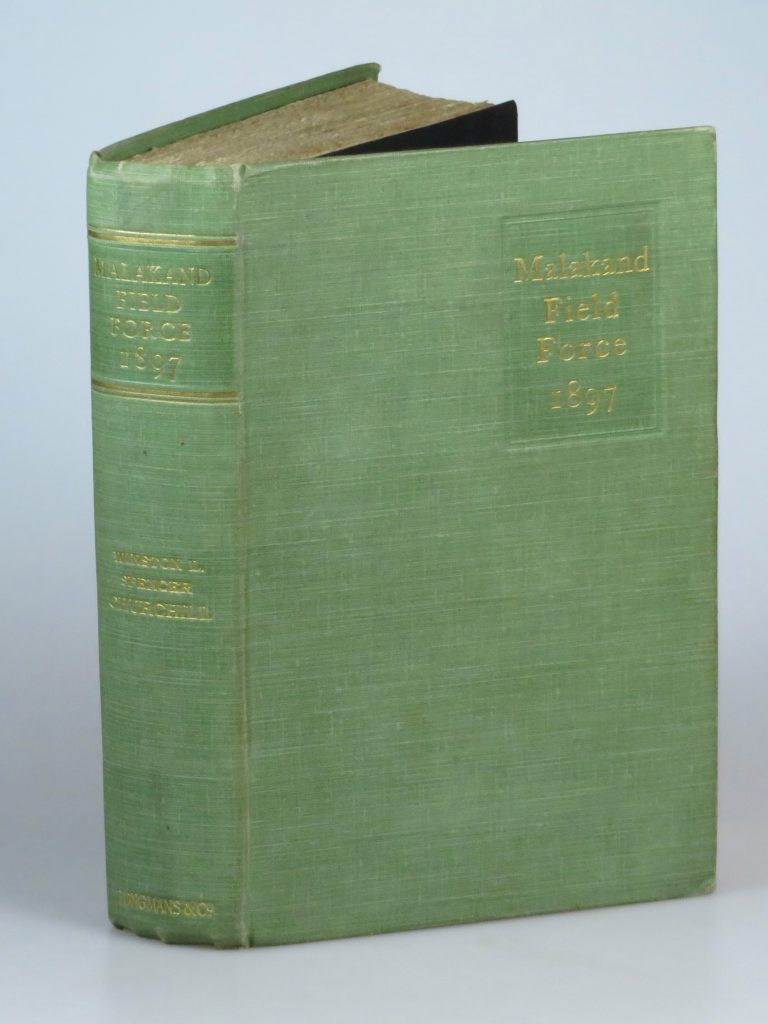

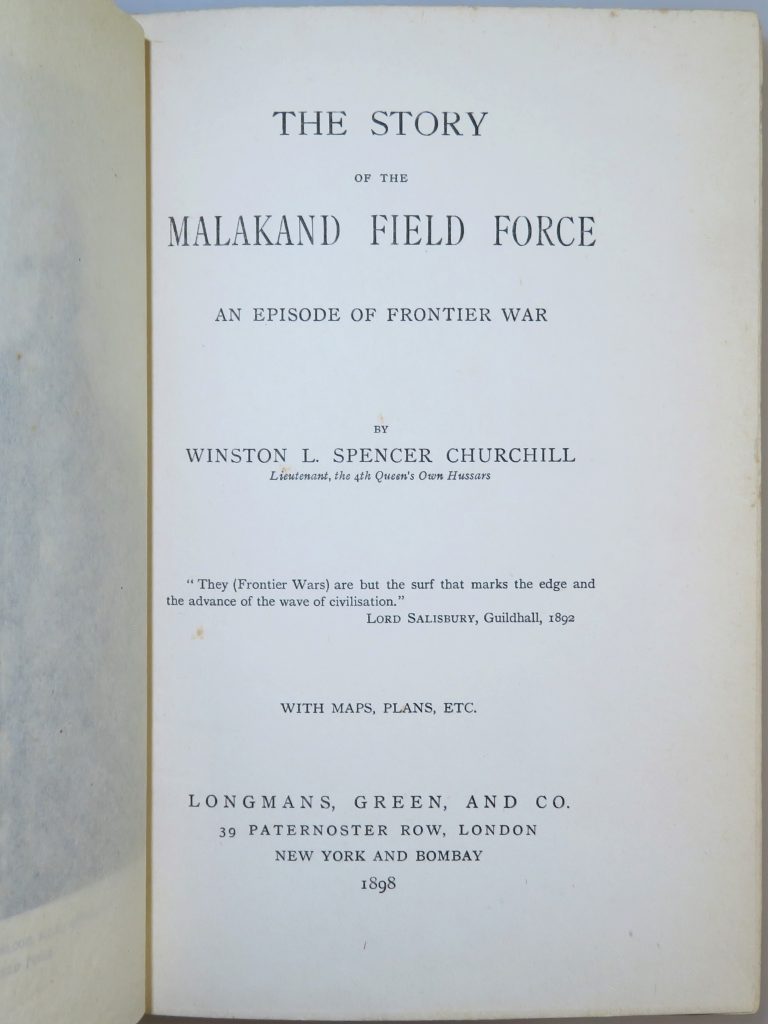

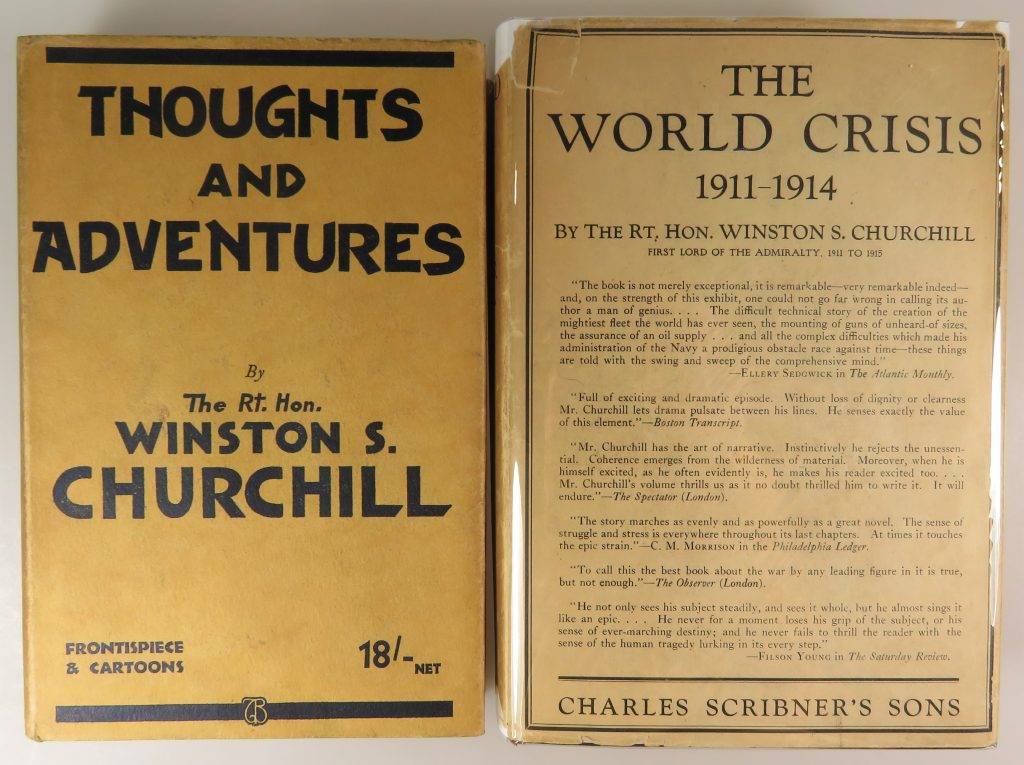

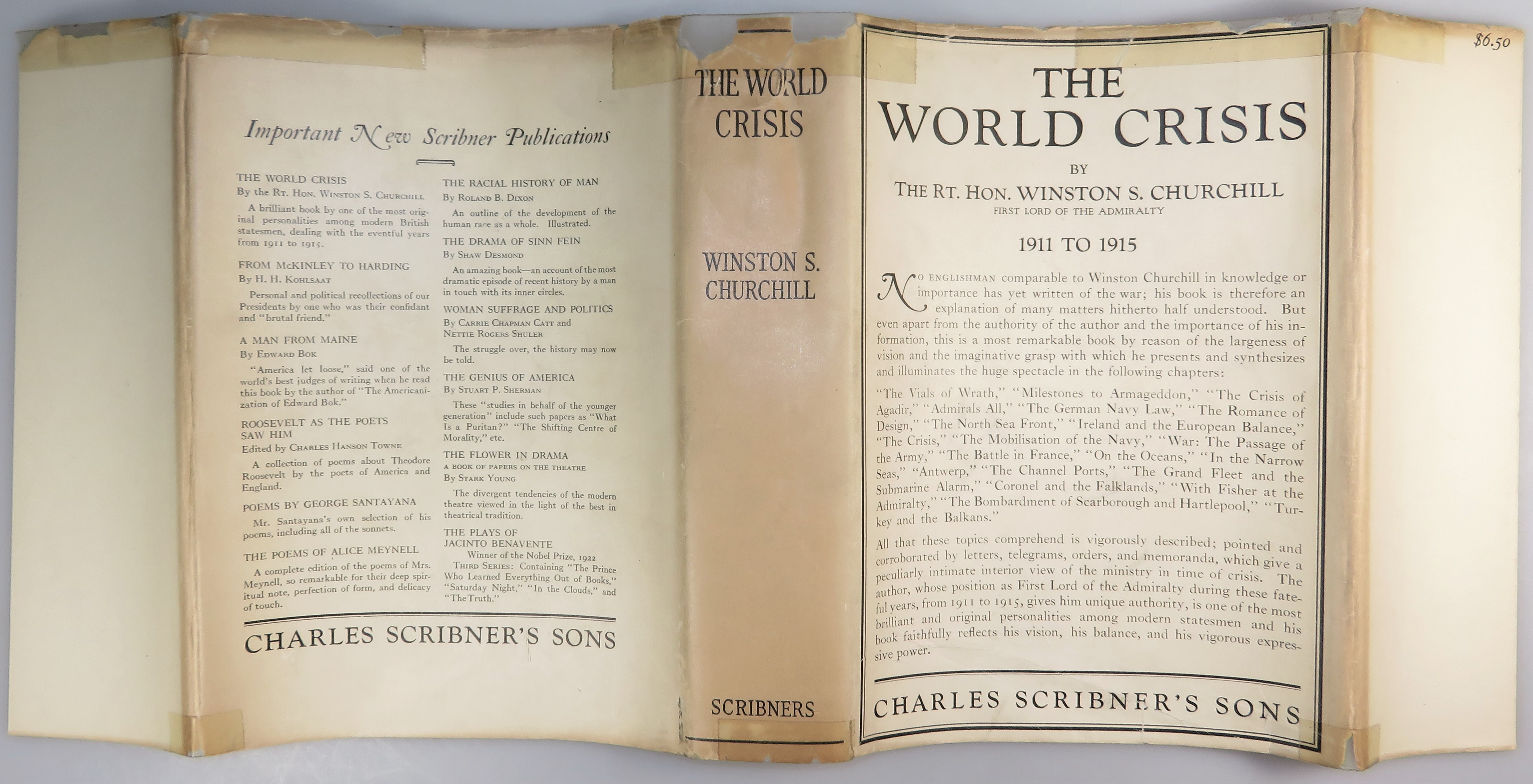

First, as the contents of our catalogue demonstrate, Churchill’s “remarkable and versatile” life was connected to a tremendous quantity and variety of extraordinary people.

Second, who we are is affected by those to whom we are connected – whether by direct experience and association or mere acquaintance and regard. An individual’s “six degrees” are the gut bacteria of their personality – prolific, symbiotic, cumulatively vital, and experientially inseverable.

Third, the “six degrees” hypothesis reminds us that many distances – whether between people or between divergent places and perspectives – may be less than we suppose. But the sundering distances created by time are different.

History recedes. Not just in time, but in relevance and relatability. “Now” crowds “then”. “Is” eclipses “was”. “We” decays to “they”. Degrees of separation lengthen with years. In the words of someone we tend to quote, “History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.” An understanding and appreciation for history enables the relatably small world of the six degrees hypothesis to fend – at least to a degree – the depredations of time.

Which returns me to our catalogue – and a bit of apropos bookseller numerology.

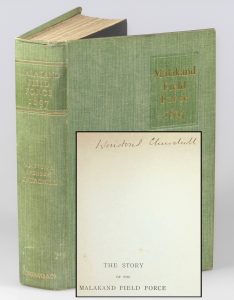

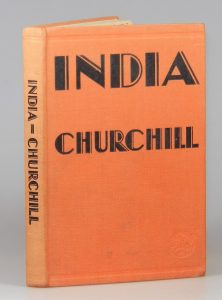

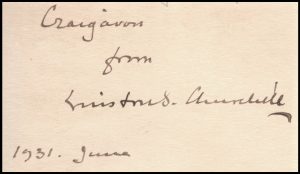

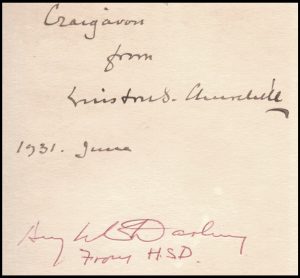

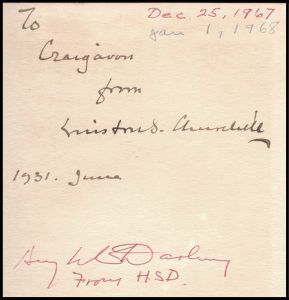

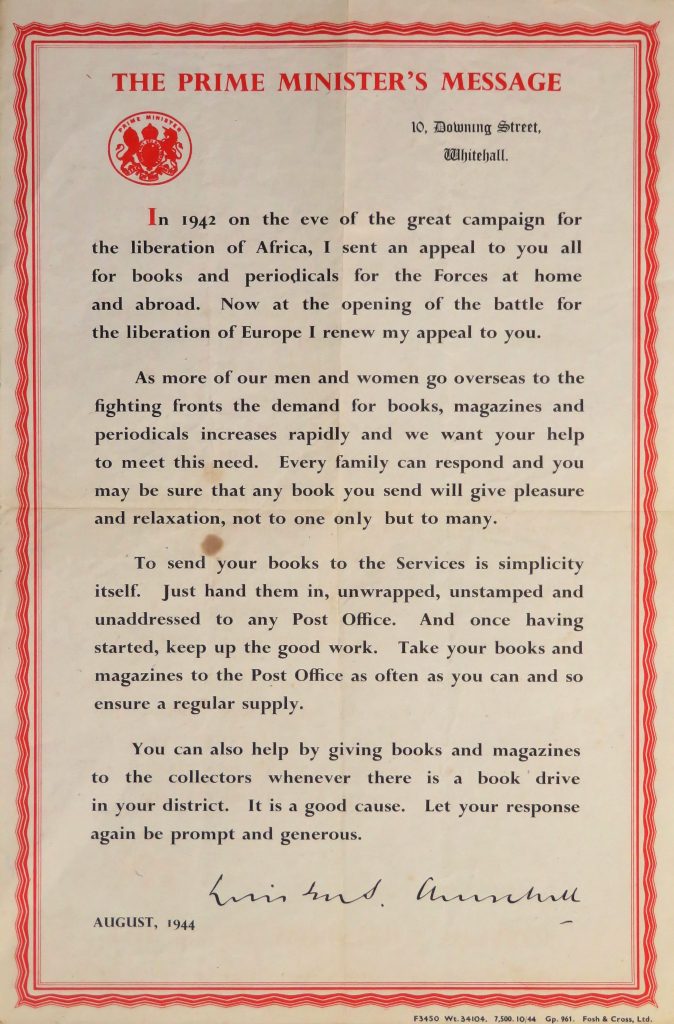

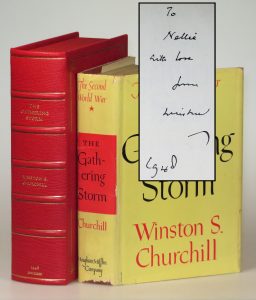

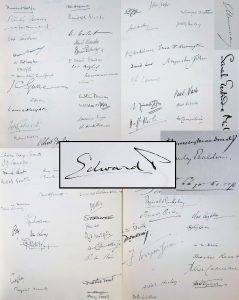

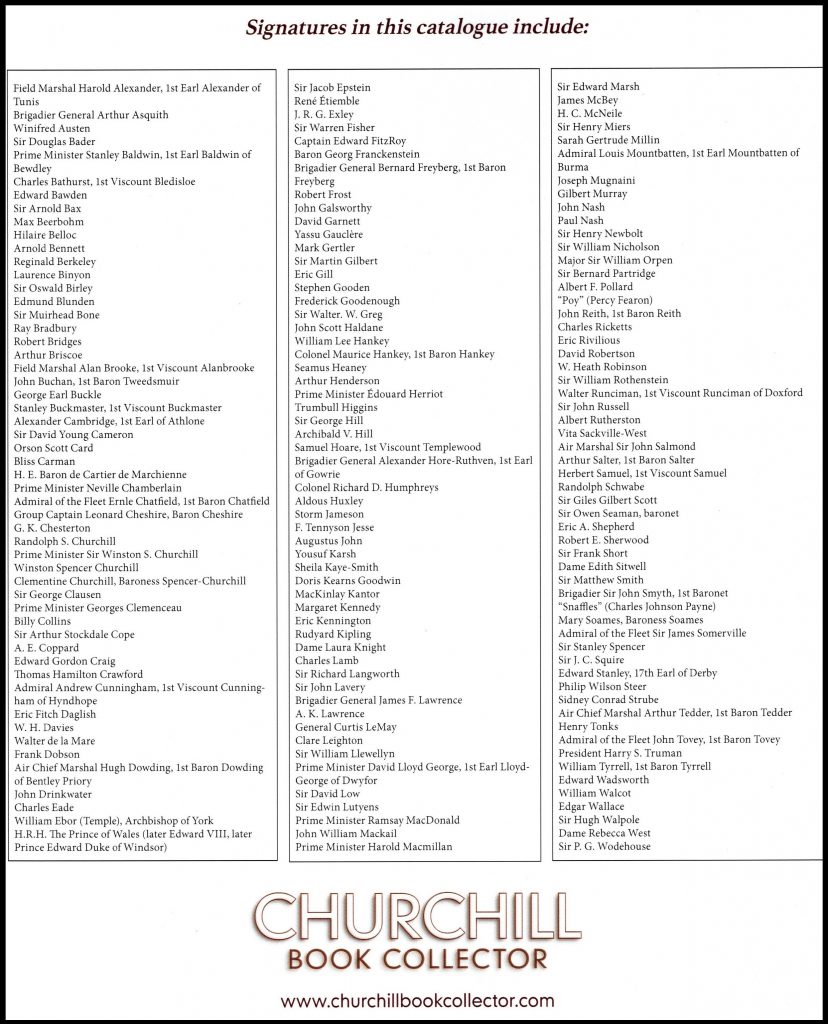

There are six times six items offered in Six Degrees of Winston. These include the signatures of sixty-six individuals. Winston Churchill’s signature is found in several catalogue items, but the balance of the signatures are those of individuals connected to his life and labors – as is he to theirs.

Among the sixty-six are prime ministers and presidents, generals and field marshals, historians, photographers, novelists, soldiers, relatives, and royalty. We did not pull off a literal “A to Z” list, but we did make A to W. Here’s the full list of signatures:

Field Marshal Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander, first Earl Alexander of Tunis

Emma Margaret “Margot” Asquith, Countess of Oxford and Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith

Roy Asser

Wing Commander P. P. C Barthropp

Wing Commander R. P. “Bee” Beamont

Squadron Leader G. H. “Ben” Bennions

Air Vice-Marshal H. A. C. Bird-Wilson

Air Commodore P. M. Brothers

Henry Worthington Bull

Pamela Frances Audrey Bulwer-Lytton (née Plowden), Countess of Lytton

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan

Baroness Clementine Ogilvy Spencer-Churchill

Jeanette “Jennie” Spencer-Churchill

Sir Winston S. Churchill

Winston S. Churchill (namesake grandson)

Sir Julian S. Corbett

Air Marshal Sir Denis Crowley-Milling

Group Captain W. D. David

Air Commodore A. C. “Al” Deere

Edward John Barrington Douglas-Scott, 3rd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu

Squadron Leader B. H. Drobinski

Flight Lieutenant J. H. Duart

Dwight David Eisenhower

Gerald R. Ford, Jr.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Christopher Foxley-Norris

Sir Martin Gilbert

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone

Group Captain T. P. “Tom” Gleave

John Golley

Ethel Anne Priscilla “Ettie” Grenfell, Baroness Desborough

William Henry Grenfell, 1st Baron Desborough

Bill Gunston

Douglas Southall Freeman

Wing Commander N. P. W. Hancock

Squadron Leader C. Haw

Commander R. C. Hay

Freddie Hurrell

Yousuf Karsh

Group Captain C. B. F. Kingcome

Colonel Henry Gaston Lafont

Richard M. Langworth

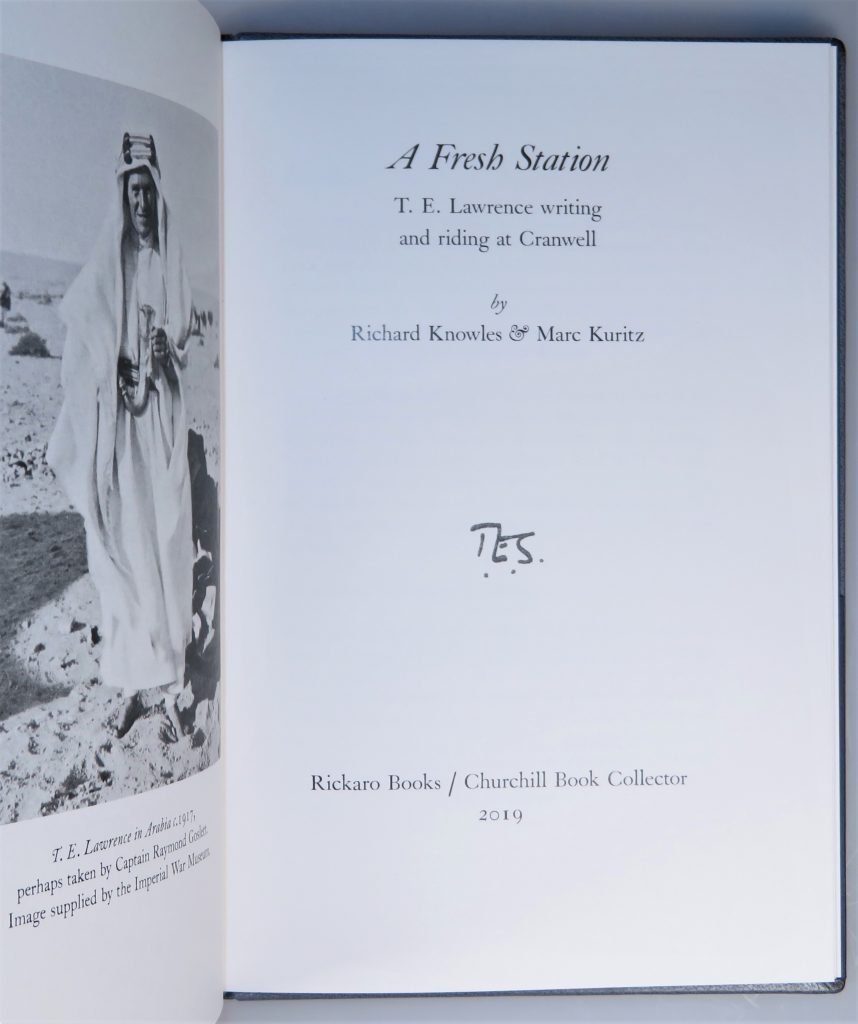

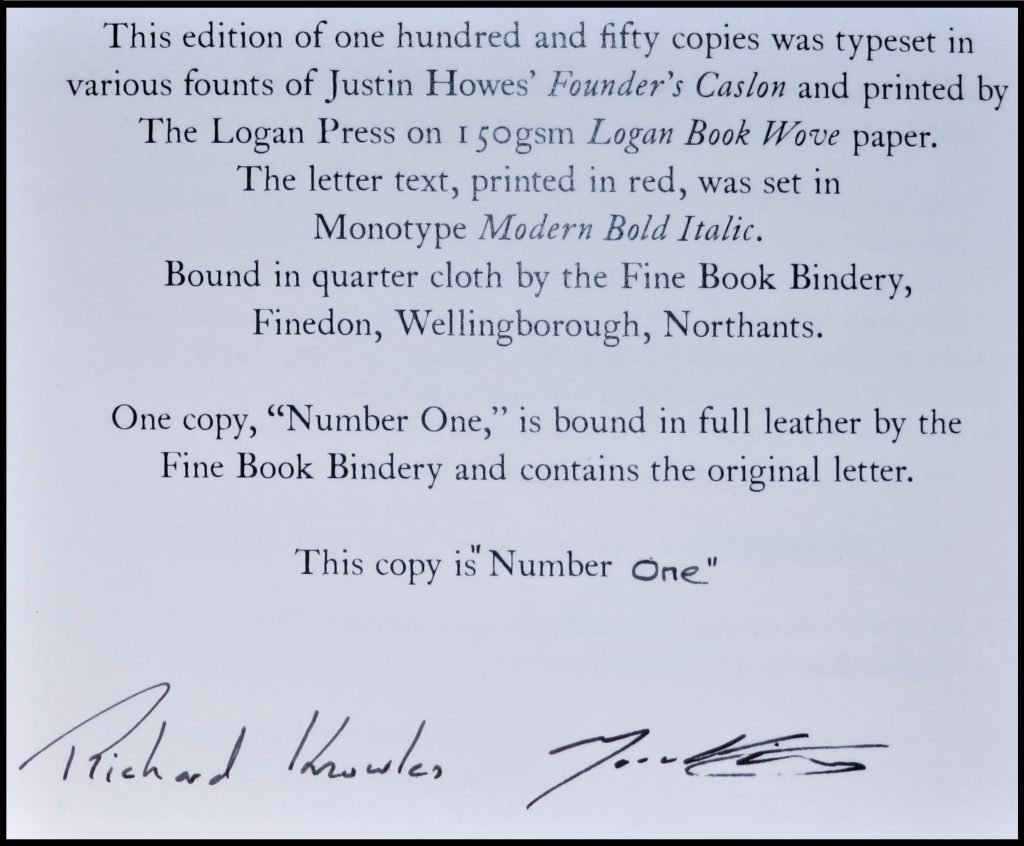

Arnold Walter Lawrence

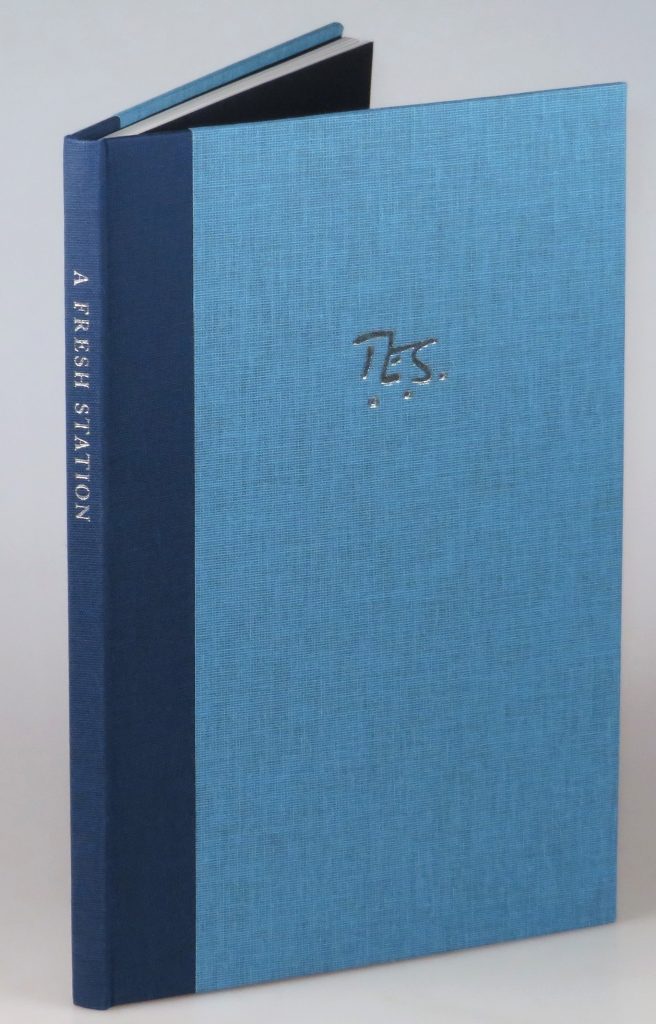

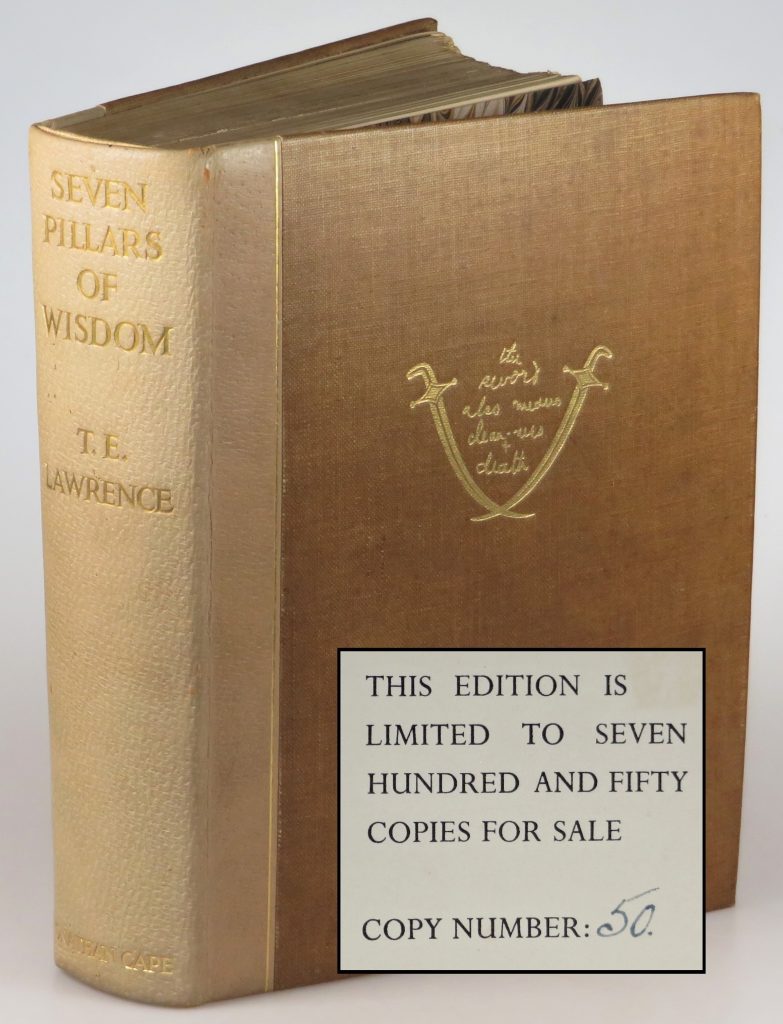

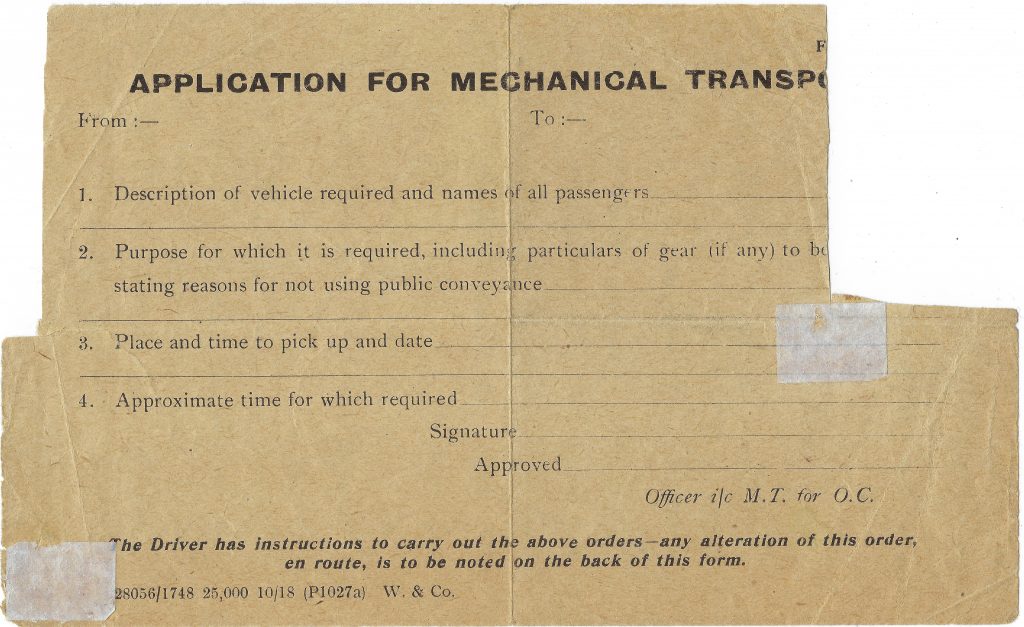

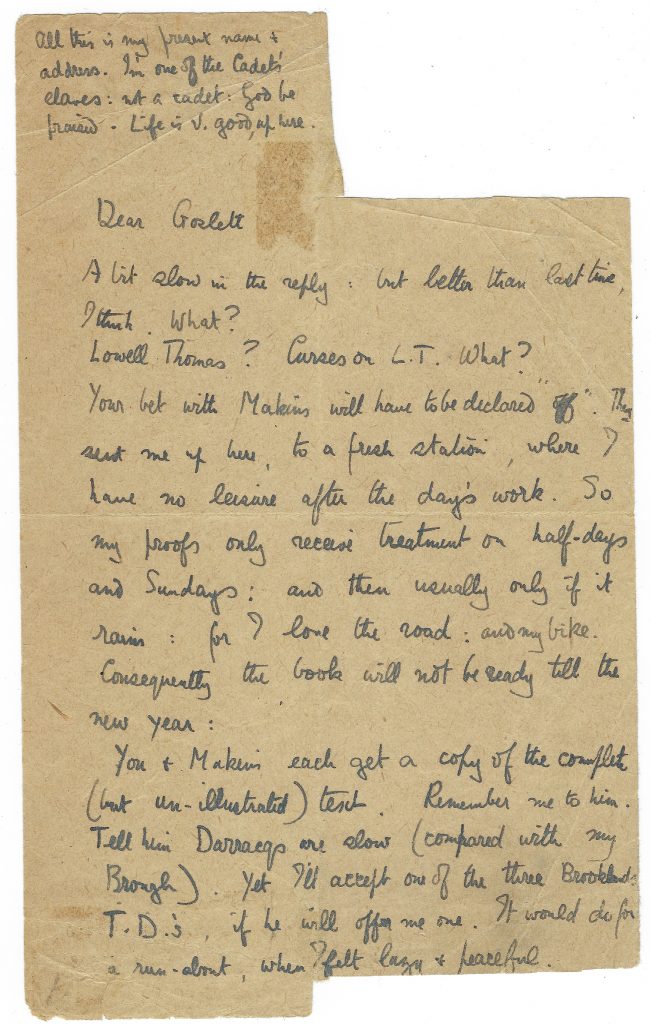

Thomas Edward Lawrence

Sir Reginald Lister

Clare Boothe Luce

Alfred Lyttelton

Edith Balfour Lyttelton

Air Commodre A. R. D. MacDonell

Squadron Leader M. J. Mansfield

Kimon Evan Marengo (nom de plume “Kem”)

Brian Masterton

John McClelland

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein

Wing Commander A. G. Page

Wing Commander P. L. Parrott

Michael Pierce

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

Group Captain D. F. B. Sheen

Wing Commander F. M. Smith

Walter Ernest Stoneman

Wing Commander J. E. Storrar

Millicent Fanny Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland (nom de plume Erskine Gower)

Harold John “Jack” Tennant

Wing Commander G. C. Unwin

Helen Venetia Vincent, Viscountess D’Abernon

Harold James Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx

Lady Cornelia Henrietta Maria Wimborne

Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor, Queen Elizabeth II

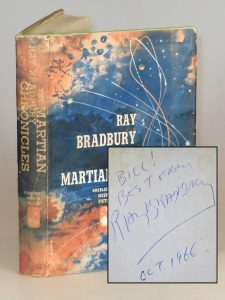

Each of the thirty-six artifacts in the catalogue signed by one or more of these individuals is a tangible link, a flicker limning that “trail of the past”, and of course, a collectable connection to Winston Churchill. We leave it to you to count the degrees.