On Wednesday, February 1st, Marc had the honor of being invited to Pasadena to address the Zamorano Club, Southern California’s oldest organization of bibliophiles and manuscript collectors, founded in 1928. His talk was titled Living Words: The Language, Life, and Leadership of Winston S. Churchill. Marc spoke for roughly 45 minutes to a full room, followed by Q&A. We include the full text of his talk below.

Greg’s a friend and he knows me pretty well. So there’s no way I would have such a nice introduction unless I paid him. Greg, thanks for taking the money.

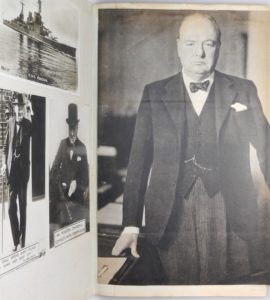

So. Winston S. Churchill. Any of you heard of this guy? World War Two. Saving Britain from the Nazis. Spokesman for freedom and democracy. Yada yada…

Yes? Good…. But the World War II – V for Victory – Blood Sweat and Tears Churchill is not the only Churchill I’m here to talk about tonight.

Yes? Good…. But the World War II – V for Victory – Blood Sweat and Tears Churchill is not the only Churchill I’m here to talk about tonight.

I’m here to talk about Churchill the wordsmith. About the living, vital, incessant torrent of words that stitched the fabric of his long and incredible life.

That’s because – like all of you here tonight – I love the splendid alchemy of words.

Ink on a page. Symbols scratched on parchment and stone. Sounds hanging in spaces between people, between centuries, between points of view…

Words are the true engine of our intelligence and perhaps the most potent instrument we use to shape the world.

To question, conceive, and span.

As you all seemed to agree back in 1928, books are a pretty darn good place to keep words.

So I hope you’ll pardon me for quoting Churchill for the first of many times tonight.

Of our books, he said: “…Peer into them. Let them fall open where they will. Read on from the first sentence that arrests the eye. Then turn to another. Make a voyage of discovery, taking soundings of uncharted seas. Set them back on your shelves with your own hands. Arrange them to your own plan, so that if you do not know what is in them, you at least know where they are.”[1]

Of our books, he said: “…Peer into them. Let them fall open where they will. Read on from the first sentence that arrests the eye. Then turn to another. Make a voyage of discovery, taking soundings of uncharted seas. Set them back on your shelves with your own hands. Arrange them to your own plan, so that if you do not know what is in them, you at least know where they are.”[1]

As a professional bookseller, I spend most of my days in the company of Churchill’s words. Thank you for inviting me to share with you a bit about the Churchill I’ve come to know.

Since I’ll be talking for a while, let me do you the courtesy of telling you what I’ll be talking about.

The title of my talk this evening is “Living Words”. Like us, Churchill loved words. But perhaps more than any of us in this room, Churchill understood – and lived – that “splendid alchemy” I was just talking about a few minutes ago.

I’ll start by giving you some of my own perspective on Churchill. Then I’ll talk about his life, his language, and his leadership – roughly in that order, but of course with some overlap.

Please note the absence of a laptop and projection system. I have given –and suffered through – entirely too many Power Point presentations. So no slides today folks.

The good news is that I have props!

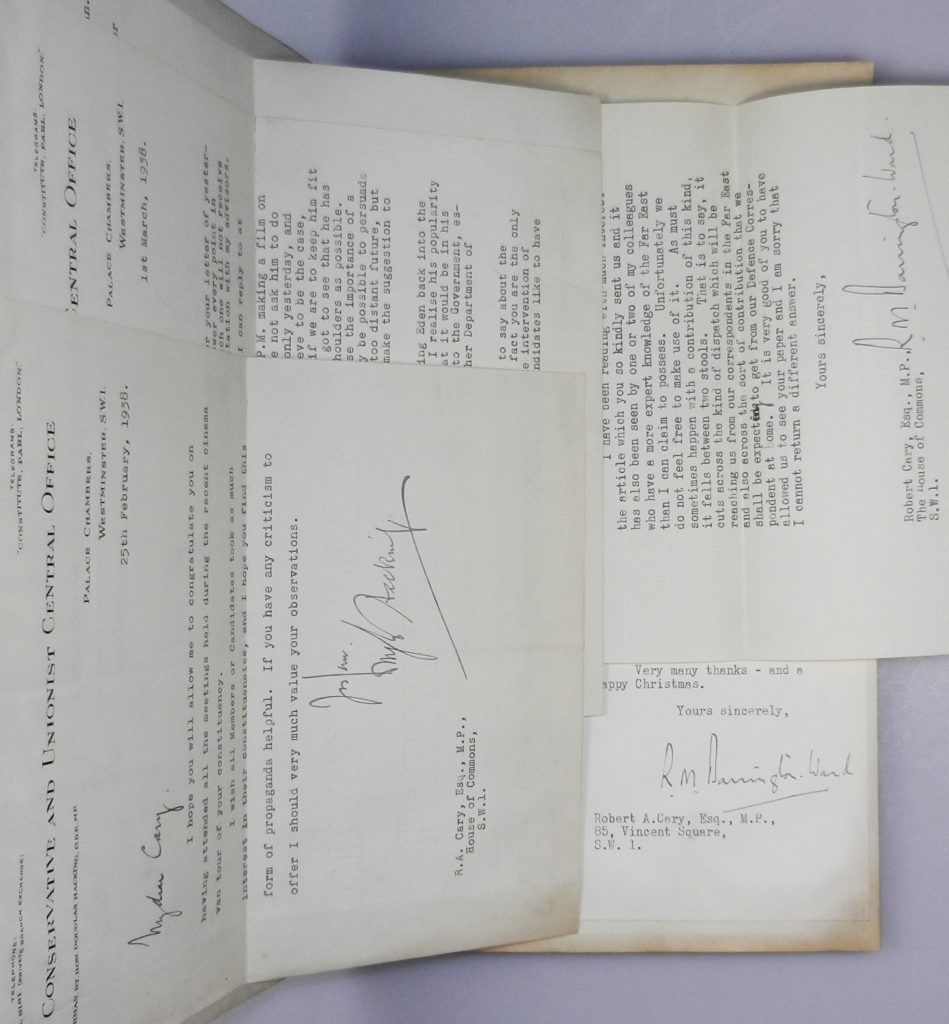

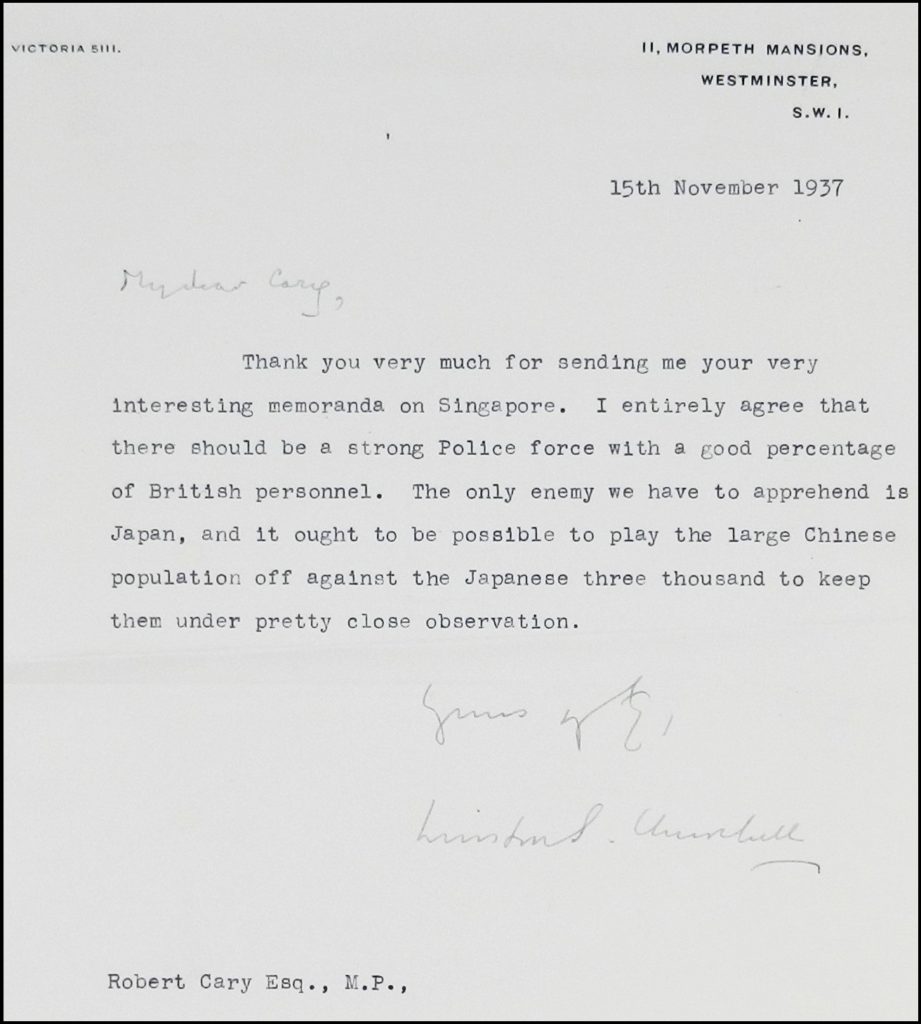

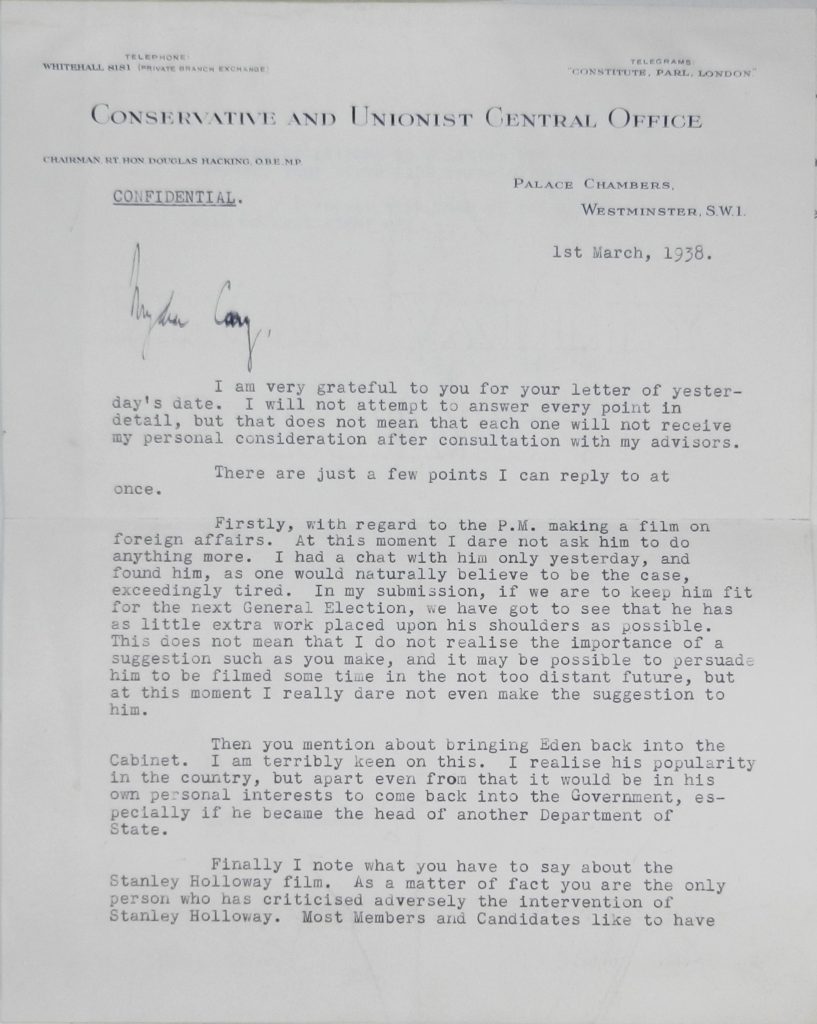

To prevent myself from lulling you to sleep, I will pass around a few precious and quite valuable objects. Please handle them with great care and please do not take any of the items that are in plastic sleeves out of the plastic sleeves.

Oh, and please do give them back.

So. Let’s talk a little about Churchill’s life.

I intend to say a lot of complimentary and interesting things about Winston Churchill today. But before I do, I want to say something else.

Fat. Lisping. Bath-taking. Jumpsuit-wearing. Privileged. Self-indulgent. Spendthrift. Brash. Egocentric. Impulsive. Impatient. Wrong. And sometimes wrong with the same bullish vigor as when he was right.

Sure, Churchill’s moral clarity would both define his long political career and shape the great struggles of the twentieth century. But in May, 1898, when he was 23 years old, this same man wrote to his mother from Bangalore: “I do not care so much for the principles I advocate as for the impression which my words produce & the reputation they give me. This sounds very terrible. But you must remember that we do not live in the days of Great Causes.”[2]

As Churchill recedes into history, there is danger in putting him on a pedestal. In marbling and bronzing him into irrelevance. He was a truly remarkable man, but still just a man. Among those who praise Churchill, there is a tendency to act as if he had unerring judgment and prescience. To envelop him in a blind and dulling reverence.

Let’s not do that.

Infallibility is boring. Churchill was anything but boring. And at times he was markedly irreverent. Why should we be any less?

My own regard for Churchill is for his intense, monumental humanity. For a magnificence of spirit, of mind, and of will that both embraces and eclipses imperfections.

LIFE

So let’s round out the picture of who Winston Churchill was.

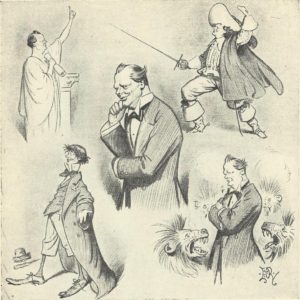

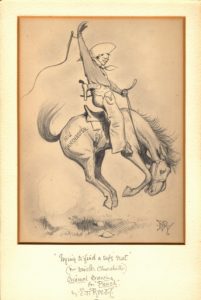

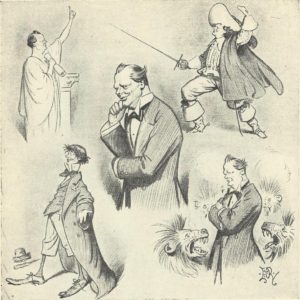

Edward Tennyson Reed Cartoon

Edward Tennyson Reed Cartoon

This is a good time for my first prop. As you might imagine, Churchill was the subject of a great many political cartoons. I have brought one from 1911, called “A Cast of Characters.”

I have always loved this cartoon. It shows – with great irreverence – so many of the roles Churchill already played with such versatility and skill nearly three decades before he became prime minister.

For better or worse, Churchill’s official biography holds the Guiness World Records title for world’s longest biography. There’s a reason.

It has become common for each generation to claim that they have experienced more change – technological, cultural, and geopolitical – than any preceding. When I hear millennials make such a claim, just because they have social media accounts and smart phones, I encourage them to consider Churchill.

The young war correspondent and British imperial soldier who participated in “the last great cavalry charge in British history” would later help design the tank, pilot aircraft, direct use of some of the earliest computers – for World War II code breaking – and ultimately preside as Prime Minister over the first British nuclear weapons test.

This icon of the British Conservative Party dramatically repudiated the Conservatives in his early career and spent 20 years as a Liberal, championing progressive causes and being branded a traitor to his class.

This soldier and scion of British imperialism wrote his first published book in a tent on the northwest frontier of colonial India. He would later bear witness to, and hold power during, devolution of the British Empire, along the way supporting causes contrary to prevailing sentiment of his caste and country – early and vigorously – such as Irish Home Rule and a Jewish national home in Palestine.

First elected to Parliament during the reign of Queen Victoria, Churchill would serve as the first Prime Minister under the currently reigning Queen Elizabeth II.

Churchill lived for more than 90 years. He spent more than 60 of these years as an elected Member of Parliament. He served in the British Cabinet during every decade for the first half of the twentieth century. He occupied high public office during both of the twentieth century’s world wars.

But even that only tells a fraction of his tale. And through it all, Churchill’s career was declared finished and resuscitated a ludicrous number of times.

Among them:

As a student, when he conspicuously failed to excel in most subjects. When he sought to attend the Royal Military College at Sandhurst he twice failed the entrance exams. He just barely qualified for infantry, and ended up taking a cavalry post. Cavalry had lower standards than infantry.

In 1904, he famously “crossed the aisle” in Parliament, leaving the Conservative Party of his father to become a Liberal.

In 1915, he was blamed for disaster in the infamous Dardanelles campaign and forced to resign from the Cabinet. He would go from heading the Royal Navy to leading a battalion in the trenches.

In 1922, he suffered both the loss of his seat in Parliament and the electoral destruction of his Liberal Party.

Throughout the 1930s. These were Churchill’s “wilderness years,” when he was out of power and out of favor, persistently seeking to draw attention, resources and resolve to face the growing Nazi threat. Churchill passed from his mid-50s into his mid-60s with his personal fortunes and those of his country ever receding.

Not until he was 65 years old did he finally become Prime Minister, and then during the most desperate circumstances for his nation and the free world.

Even after the Second World War. In 1945, Churchill’s party was voted out of office. At the end of the war he had done so much to win, he lost his premiership.

Churchill had to accept frustration of his postwar plans and settle for being Leader of the Opposition for six long years until he finally returned to 10 Downing Street in 1951 for his second and final premiership.

And these were only political losses.

Winston Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, died in January 1895 at age 45 following the spectacular collapse of both his health and political career. His son Winston was 20 years old.

Churchill lost a daughter to illness in 1921. And another to suicide in his final years.

He lost his fortune to the stock market crash of 1929.

During both of his premierships, he struggled with his health, to maintain and project the vitality that his responsibilities demanded.

But Churchill is even more than an epic tale of resolve and resilience. Much more, actually. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Churchill’s life is his extraordinary breath of both mind and experience.

Before his mid-twenties, Churchill managed to become one of the highest paid war correspondents in the world. He reported from battlefields on three different continents, but also saw more than his share of fighting, including capture and a daring, improbable escape during the Boer War in South Africa.

Fascinated by powered flight, Churchill was a pilot.

During the terrible trench warfare stalemate of the First World War, it was Churchill who helped conceive and promote the tank, ushering in the age of mobile warfare. Mind you, at the time he was in charge of the Navy.

In the darkest days of that war, Churchill discovered painting, which became a passion and source of release and renewal for the remaining half century of his long life. He would ultimately paint more than 500 canvasses.

An implacable foe of Germany in two world wars, Churchill would help conceive and advocate the two transnational institutions most responsible for promoting peace in the world – the United Nations and European Union.

Churchill championed both Irish home rule and a Jewish national home in Palestine – early, ardently, and consistently.

And these were only a few among many progressive causes that the Conservative icon championed, defying the agendas of both his party and class.

It was Churchill who, in the first decades of the twentieth century, did so much to lay the foundations of the modern welfare state, not only championing social programs, but also the funding for them, supporting a graduated income tax, luxury tax, and surtaxes on unearned income.

LANGUAGE

We could easily fill our evening talking just about the events of Churchill’s life. But there were no shortage of great figures and great deeds in the twentieth century. So I’d like to talk about what made Churchill’s life so compelling – his language and his leadership.

Language first.

Perhaps more than anything else, Churchill was a master wordsmith.

And this was no accident.

In an unpublished essay he penned in 1897, Churchill wrote:

“Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory.

He who enjoys it wields a power more durable than that of a great king.

He is an independent force in the world.

Abandoned by his party, betrayed by his friends, stripped of his offices,

whoever can command this power is still formidable.”

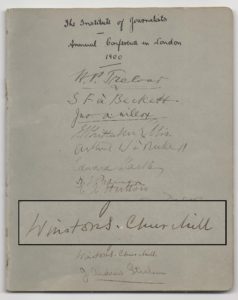

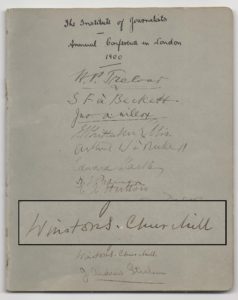

Journalists’ conference autograph booklet

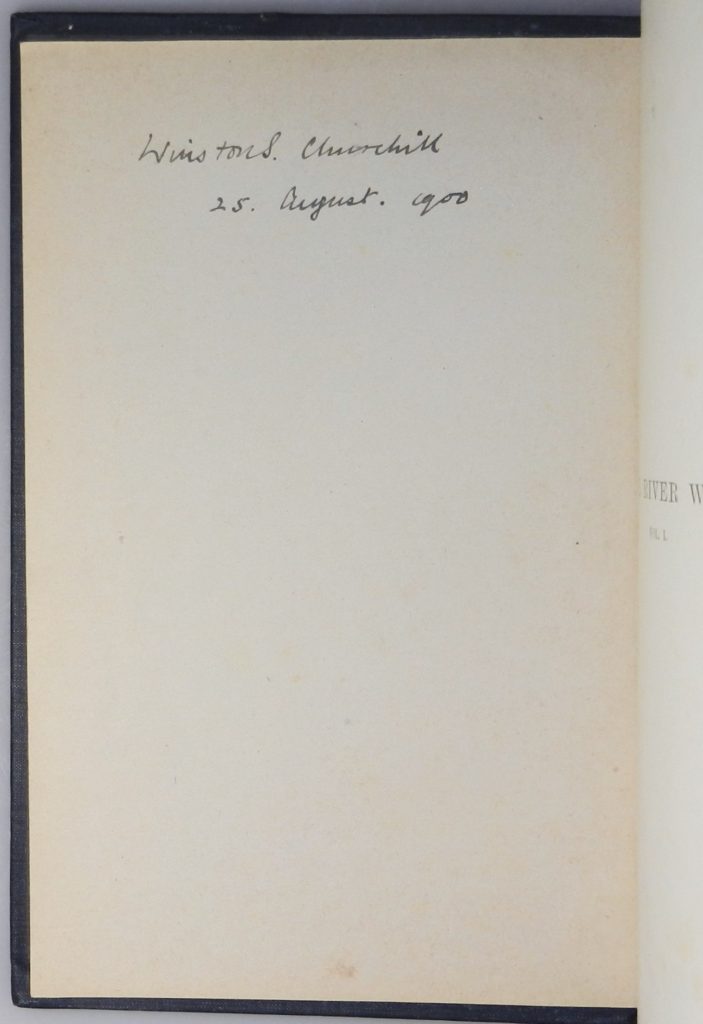

This is a good time for another prop. Remember I said that Churchill had an early – and quite successful – career as a war correspondent.

I’m going to pass around a truly unique item we were pleased to discover a few years ago. This is an autograph booklet from the September 1900 Institute of Journalists annual conference in London, signed by a young Winston Churchill and 28 other of his fellow journalists.

In September 1900, Winston Churchill was just 25 years old, a soldier and war-correspondent who had yet to hold elected office. On September 8th, 1900, Churchill wrote to his mother: “My dear Mamma, I am sorry not to be able to come until Wednesday morning, but I thought it better to attend the Annual Dinner of the Conference of the Institute of Journalists, at which I have been invited to reply for the war-correspondents. It is a good thing now and again to make a speech unconnected with politics and it is also a good thing, and opportunity not to be missed, to speak before the writers of Great Britain…” [3]

In September 1900, Winston Churchill was just 25 years old, a soldier and war-correspondent who had yet to hold elected office. On September 8th, 1900, Churchill wrote to his mother: “My dear Mamma, I am sorry not to be able to come until Wednesday morning, but I thought it better to attend the Annual Dinner of the Conference of the Institute of Journalists, at which I have been invited to reply for the war-correspondents. It is a good thing now and again to make a speech unconnected with politics and it is also a good thing, and opportunity not to be missed, to speak before the writers of Great Britain…” [3]

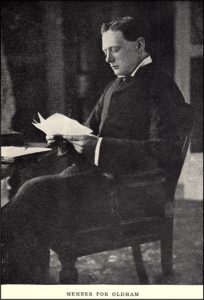

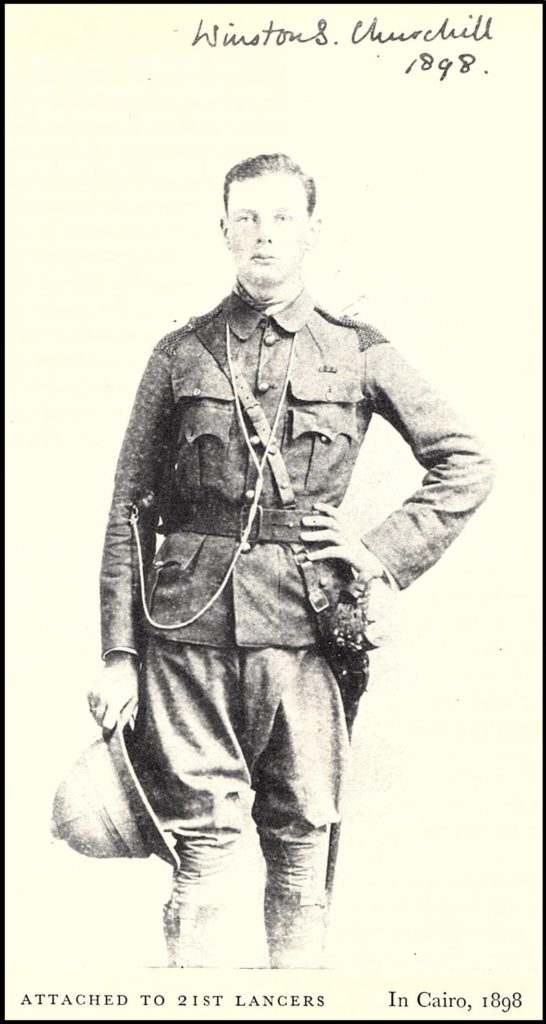

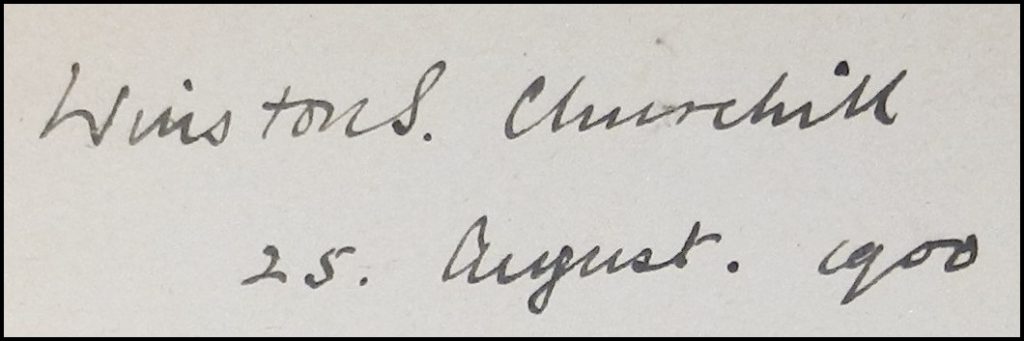

We have found no record that preserves Churchill’s remarks at the Dinner, but his autograph we’re passing around proves that he attended. Likely it was less “unconnected with politics” than Churchill let on. Less than a month after he signed this booklet, on October 1st 1900, Churchill won his first seat in Parliament in the so-called “khaki election”. Churchill had returned from the Boer War only in July 1900, spending the summer campaigning hard in Oldham and capitalizing on his capture and daring escape, and war dispatches from South Africa. It was a still very 19th Century Churchill who left this signature in this autograph book. After the election, Churchill would leave for his first North American lecture tour. While Churchill was abroad, Queen Victoria died, and the end of her 64-year reign also closed Churchill’s Victorian career as a cavalry officer and war correspondent adventurer. Churchill returned to England in February 1901 to take his seat in Parliament and begin a 60-year career as one of the 20th Century’s great statesmen. Again, please don’t take this item out of the protective sleeve.

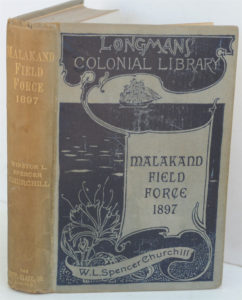

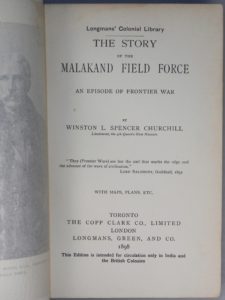

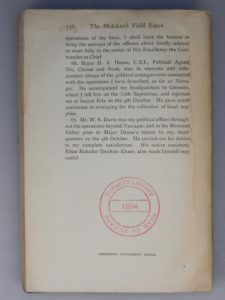

Churchill was 23 when his first book was published – The Story of the Malakand Field Force. It was based on his dispatches to the Daily Telegraph and the Pioneer Mail, but this was his first book-length work.

Ambition was clearly a motivation. In November 1897, he wrote to his mother of the book project: “…It is a great undertaking but if carried out will yield substantial results in every way, financially, politically, and even, though do I care a damn, militarily.” [4]

Having invested his ambition in the book, he clearly labored over it: “I have discovered a great power of application which I did not think I possessed. For two months I have worked not less than five hours a day.”[5] The finished manuscript was sent to his mother on the last day of 1897 and published on March 14th, 1898.

Many, many more words would follow. Before his death in January 1965, Churchill’s published works would run to:

- 58 books

- 260 pamphlets

- More than 840 feature articles

- 9,000 pages of speeches

Just the Bibliography of Churchill’s published works requires three volumes.

What’s so special about all these words?

Why should we care about the words of a 20th century politician with some distinctly 19th century sensibilities?

Because of what he saw and how he wrote it. Because we still – maybe even more than ever – use words to frame the world as we see it and to share what we see with others. And Churchill both saw more and framed his perceptions more compellingly than perhaps any world leader before or since.

Let me read a few more of Churchill’s words to you…

This is an excerpt from the opening of Churchill’s first published book – the one I mentioned a few minutes ago – The Story of the Malakand Field Force. Remember that Churchill wrote this book in a tent while serving as a cavalry officer on the northwest frontier of colonial India. This passage is from page 47:

“…the great frontier war had begun. The noise of firing echoed among the hills…

One valley caught the waves of sound and passed them to the next,

till the whole wide mountain region rocked with the confusion of the tumult.

Slender wires and long-drawn cables carried them to the far-off countries of the West.

Distant populations on the Continent of Europe thought that in them

they detected the dull, discordant tones of decline and fall.

Families in English homes feared that the detonations marked the death of those they loved – sons, brothers or husbands.

Diplomatists looked wise, economists anxious, stupid people mysterious and knowledgeable.”[6]

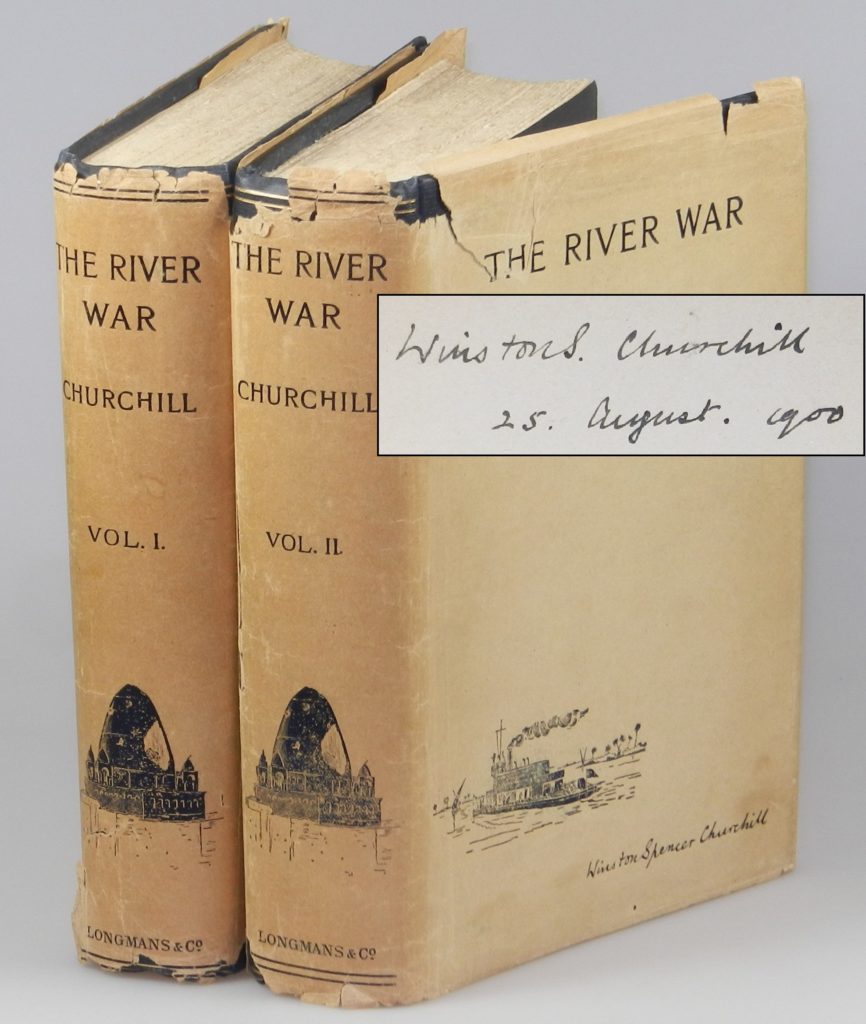

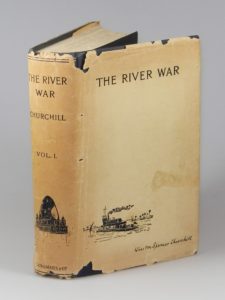

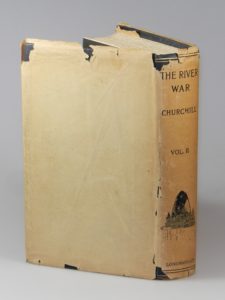

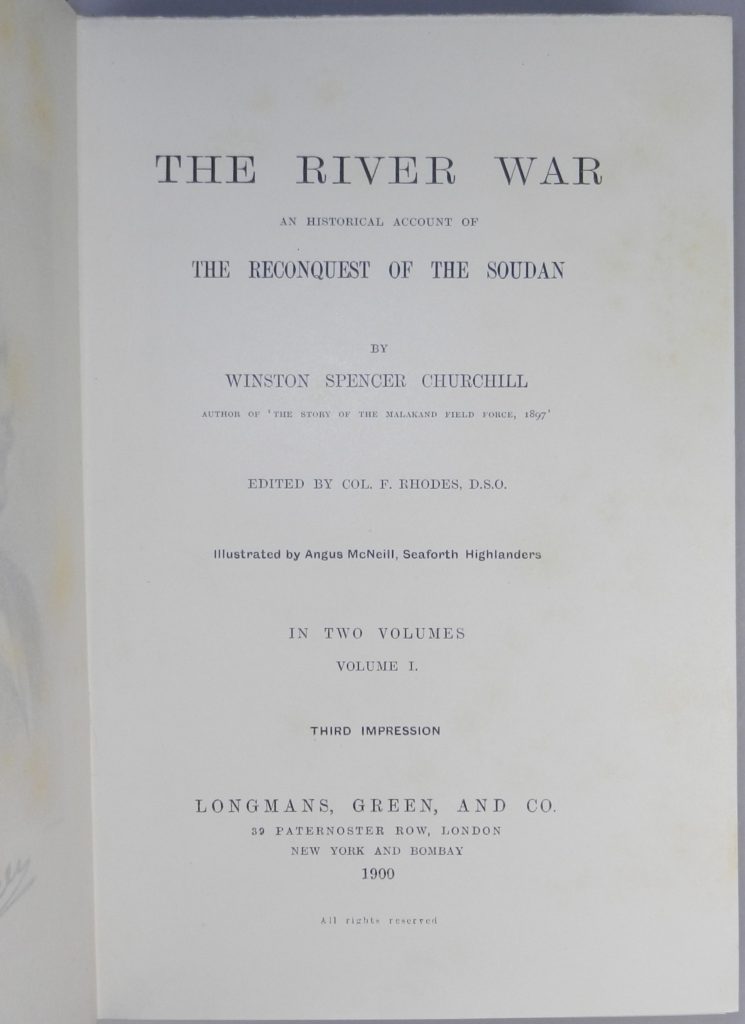

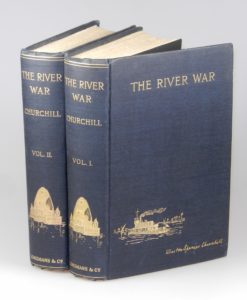

Next, a passage from The River War, Churchill’s second published book. The text is arresting, insightful, powerfully descriptive, and of enduring relevance. Mohammed Ahmed was a messianic Islamic leader in central and northern Sudan in the final decades of the 19th century. In 1883 the Mahdists overwhelmed the Egyptian army of British commander William Hicks, and Great Britain ordered the withdrawal of all Egyptian troops and officials from the Sudan.

In 1885, General Gordon famously lost his life in a doomed defense of the capitol, Khartoum, where he had been sent to lead evacuation of Egyptian forces.

The Mahdi died in 1895, but his theocracy continued until 1898, when General Kitchener reoccupied the Sudan. With Kitchener was a very young Winston Churchill, who would participate in the battle of Omdurman in September 1898, where the Mahdist forces were decisively defeated. In this book about the British campaign in the Sudan, Churchill – a young officer in a colonial British army – is unusually sympathetic to the Mahdist forces and critical of Imperial cynicism and cruelty.

This passage is from Churchill’s reflections on the Battle of Omdurman:

“… it was evident that they [the Dervishes] could not possibly succeed…

Nevertheless… they rode unflinchingly to certain death….

The valour of their deed has been discounted by those who told the tale.

‘Mad fanatacism’ is the depreciating comment of their conquerors.

I hold this to be a cruel injustice…. Why should we regard as madness in the savage what would be sublime in civilised men?

I hope that if evil days should come upon our own country, and the last army which a collapsing Empire could interpose between London and the invader were dissolving in rout and ruin, that there would be some

– even in these modern days – who would not care to accustom themselves to a new order of things and tamely survive the disaster.”[7]

No doubt – Churchill could be nakedly ambitious, fiercely partisan, and relentless in pursuit of a policy or cause. But even in Churchill’s early works there always seems to be an underpinning sense of balance. Ultimately, he always seemed able to reconcile a perspective broader – and sometimes fundamentally different – than his own. As he did that on the battlefield at Omdurman, so too he did it even in his first years in Parliament.

Free trade was a significant issue in Churchill’s early career – one of the policy issues that led to his break with the Conservative Party in 1904. In this passage from his 1906 book of speeches on the subject, note how his support for the issue – vigorous enough for him to publish an entire book on the subject – is nonetheless tempered and nuanced.

“There is another danger which we must not overlook.

Free Trade is a condition of progress; it is an aid to progress; it is a herald of progress;

but it is not progress. Something more than that is needed.

Free Trade will never be securely defended by a purely negative policy.

It is quite true that the combined influences of free imports and natural advantages

have produced in this country a much greater accumulation of wealth…

But we shall make ourselves ridiculous if we go about saying,

in a world with so much squalor and misery,

how happy, how wealthy, how contented, how luxurious we are.

We must produce, if we are successfully to defend Free Trade,

a positive and practical policy of social reform.”[8]

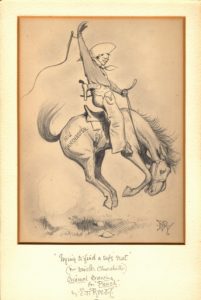

“Trying to Find a Safe Seat”

Which brings me to a suitable prop. This is another pencil cartoon by Edward Tennyson Reed, but this one is the original drawing from 1908 in a circa 1930s frame.

Churchill was 33 years old. He had been the Liberal Member of Parliament for Manchester Northwest since the 1906 General Election, but was forced to stand again for the seat in 1908, following his appointment as President of the Board of Trade – a Cabinet post. Churchill lost the election to the Conservative candidate largely because of his support of Free Trade.

I love this cartoon. The western apparel and motif plays on the fact that Churchill’s mother was American and deftly cues Churchill’s brash, maverick nature. Churchill would be bucked many times by public opinion – and just as many times he would climb right back in the saddle.

Published in November 1908, My African Journey, was a travelogue written by Churchill while he was serving as Undersecretary of State for the Colonies. In the summer of 1907 Churchill left England for “a tour of the east African domains.” By now a seasoned and financially shrewd author, Churchill arranged to profit doubly from the trip, first by serializing articles in Strand Magazine and then by publishing a book based upon them. Churchill’s language is powerfully evocative, a harbinger of his ability evoke a sense of place and time that he would use to such powerful effect in his war speeches three decades later:

“The aspect of Mombasa as she rises from the sea and clothes herself with form and colour at the swift approach of the ship is alluring and even delicious. But to appreciate all these charms the traveler should come from the North. He should see the hot stones of Malta, baking and glistening on a steel-blue Mediterranean. He should visit the Island of Cypress before the autumn rains have revived the soil, when the Messaoria Plain is one broad wilderness of dust, when every tree – be it only a thorn-bush – is an heirloom, and every drop of water is a jewel…”[9]

Almost always, there seemed an undercurrent of philosophy and broader perspective beneath Churchill’s writing and speeches. Something more than the moment. The historian and philosopher Isaiah Berlin would later write of Churchill: “Mr. Churchill’s dominant category, the single, central organizing principle of his moral and intellectual universe, is an historical imagination so strong, so comprehensive, as to encase the whole of the present and the whole of the future in a framework of a rich and multi-coloured past.”[10]

Even in his more casual writing, this sense of history permeated Churchill’s words. In a 1931 essay – published nearly 14 years before the Allies would drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima – Churchill wrote:

“Certain it is that while men are gathering knowledge and power

with ever-increasing and measureless speed,

their virtues and their wisdom have not shown any notable improvement

as the centuries have rolled. The brain of a modern man does not differ in essentials

from that of the human beings who fought and loved here millions of years ago…

We have the spectacle of the powers and weapons of man far outstripping

the march of his intelligence; we have the march of his intelligence

proceeding far more rapidly than the development of his nobility.

We may well find ourselves in the presence

of ‘the strength of civilization without its mercy’.”[11]

To be sure, not all was philosophy and history. Churchill was a politician by vocation and pugnacious by temperament. So his wit and tongue were sharp. And when he was wrong or intemperate or vulgar, it was with Churchillian panache. Churchill opposed Indian independence and called Gandhi: “a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well-known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace…”

Even the unflappable Gandhi was pricked and goaded. As were most who suffered – deservedly or not – the scourge of Churchill’s tongue and ink.

Churchill said of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald:

“We know that he has, more than any other man, the gift of compressing the largest amount of words into the smallest amount of thought.”

Of Lord Charles Beresford, a British Admiral and Member of Parliament, Churchill said:

“He is one of those orators of whom it was well said: Before they get up, they do not know what they are going to say; when they are speaking, they do not know what they are saying; and when they have sat down, they do not know what they have said.“

During his days as a young reformer and lion of the Liberal Party, Churchill said of Joseph Chamberlain:

“Mr. Chamberlain loves the working man, he loves to see him work.”

It would be Joseph’s son, Neville Chamberlain, who Churchill would in turn savage, serve with, and then magnificently eulogize more than 30 years later.

Churchill had a reputation for gallantry toward women, but with proper provocation even a woman could receive a full Churchillian fusillade. When Bessie Braddock, a Member of Parliament told Churchill: “Winston, you are drunk, and what’s more you are disgustingly drunk.” Churchill replied “Bessie, my dear, you are ugly, and what’s more, you are disgustingly ugly. But tomorrow I shall be sober and you will still be ugly.”

It may be no credit to Churchill that he was, in fact, paraphrasing W. C. Fields. In the interests of history, I should point out that Churchill was just tired, not drunk, and Bessie – well Bessie really was not a pretty woman.

Apparently Churchill did not find French general and statesman Charles de Gaulle attractive either. The man whose pretentions Churchill would prop up, promote, and support throughout the Second World War, Churchill privately likened to:

“A female llama who has been surprised in her bath.”

As an aside, do take a look sometime. The resemblance is uncanny…

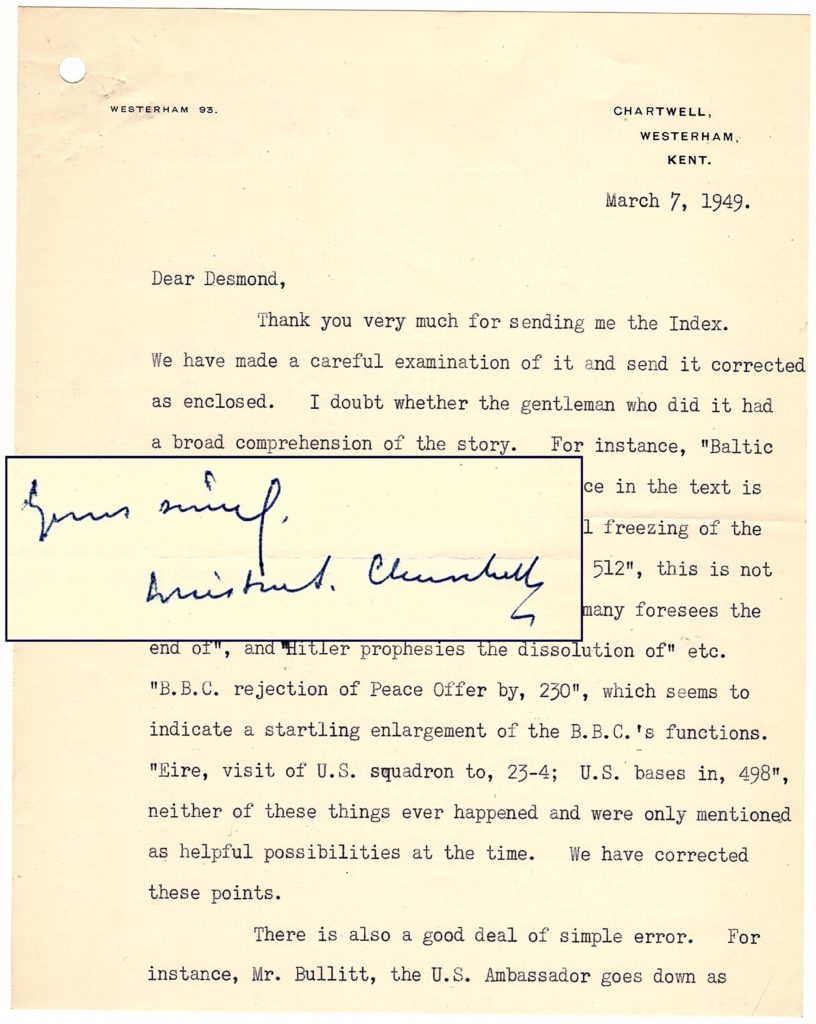

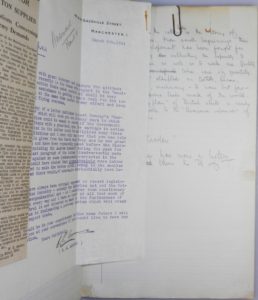

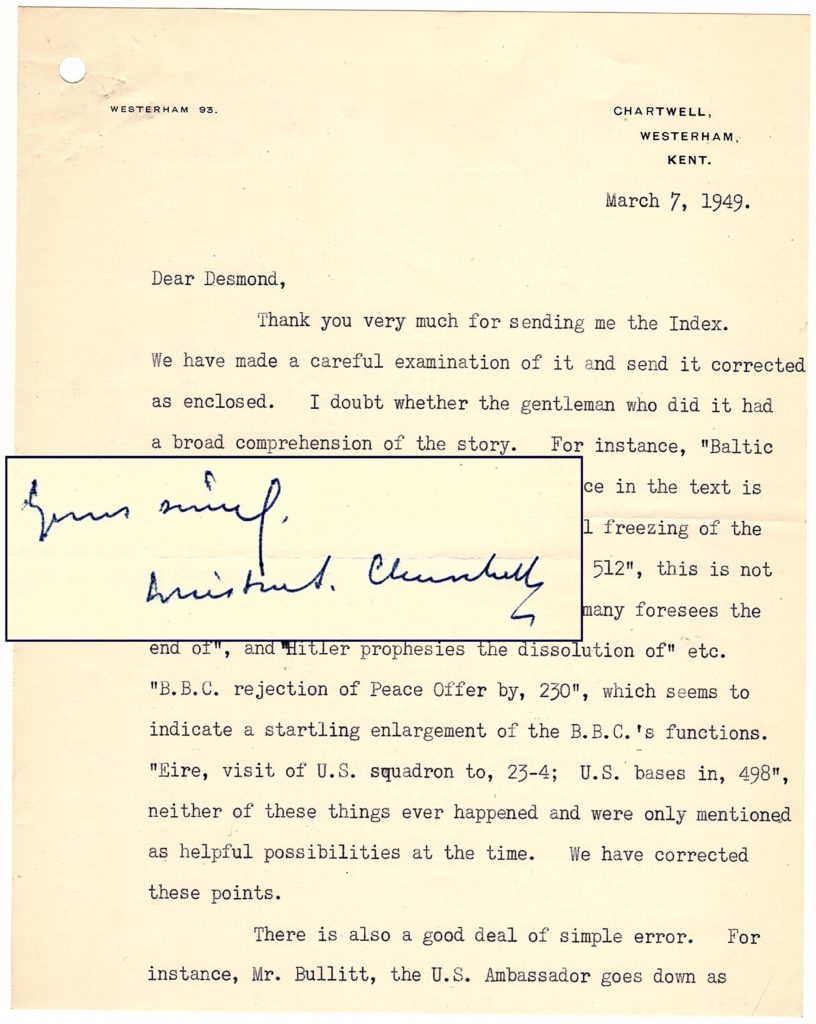

March 7th, 1949 letter from WSC to Desmond Flower

Time for another prop.

The letter I’m going to pass around is from March 7th, 1949 from Churchill to his publisher, Desmond Flower. Flower’s father, Newman, had secured what was called “perhaps the greatest coup of twentieth century publishing.” This was, of course, the rights to Churchill’s Second World War Memoirs.

But landing Churchill had its price. Monetary and otherwise.

In this two page letter, Churchill – who had an entire literary team mind you – personally offers quite granular corrections. To the Index of the second volume.

Of particular note is the lovely bit of cutting sarcasm at line 10 of the first paragraph. Churchill notes an index reference to “B.B.C. rejection of Peace Offer by”. B.B.C. was – and of course remains – the British Broadcasting Corporation, which certainly does not have plenipotentiary diplomatic powers. Churchill, rather than just pointing out the error – dryly adds that this language “seems to indicate a startling enlargement of the B.B.C.’s functions.”

Of particular note is the lovely bit of cutting sarcasm at line 10 of the first paragraph. Churchill notes an index reference to “B.B.C. rejection of Peace Offer by”. B.B.C. was – and of course remains – the British Broadcasting Corporation, which certainly does not have plenipotentiary diplomatic powers. Churchill, rather than just pointing out the error – dryly adds that this language “seems to indicate a startling enlargement of the B.B.C.’s functions.”

You can picture the hapless publisher and his editorial staff being micromanaged and scolded by an author of Churchill’s stature – one they can neither control nor do without.

To be fair, Churchill also did not stint to direct his own quips at himself:

Once, while preparing to be interviewed, Churchill started scribbling furiously on his notepad and said:

“I’m just preparing my impromptu remarks.”

And of his own fallibility, Churchill once said:

“In the course of my life I have often had to eat my words, and I must confess that I have always found it a wholesome diet.”

On May 10th, 1940, Churchill became Prime Minister. It was the position to which people had speculated Churchill would rise for more than 40 years. But he had not attained the office until he was 65 years old and Britain at perhaps her most desperate moment in her long history. On May 13th, three days after Germany invaded the Low Countries and France, Churchill gave his first speech as prime minister to the House of Commons. It was also broadcast to the public. Churchill had taken only three days to form a coalition government. His address was just four paragraphs long. He – and the nation he led – were in the crucible. The tone he set was the tone that would see him and his people through the long five years to come. His speech concluded thus:

“I would say to the House, as I have said to those who have joined this Government:

‘I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.’

You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air,

with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us:

to wage war against a monstrous tyranny,

never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime.

That is our policy.

You ask, What is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory –

victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror,

victory, however long and hard the road may be;

for without victory, there is no survival.

Let that be realised; no survival for the British Empire; no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forward towards its goal.

But I take up my task with buoyancy and hope.

I feel sure that our cause will not be suffered to fail among men.

At this time I feel entitled to claim the aid of all,

and I say, “Come, then, let us go forward together with our united strength.”

Churchill’s words – sober and soaring, defiant and resolute – would fill the next five years of conflict. I could exhaust our evening on passages from Churchill’s war speeches. I’ll limit myself to just one more. This from the aftermath of the Battle of Britain. On August 20th, 1940, Churchill addressed Parliament. The address was occasioned by the Battle of Britain. Germany had thrown the full might of her air power at Britain in preparation for a land invasion. Britain’s heroic, improbable, and very narrow victory kept Nazi Germany on the other side of the English Channel. In his speech, Churchill famously honored the Royal Air Force pilots who almost single-handedly prevented Nazi invasion of England. Churchill encapsulated and immortalized the struggle when he uttered these words:

“The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire,

and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty,

goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds,

unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger,

are turning the tide of the world war by their prowess and by their devotion.

Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

The end of the war brought deep disappointment to Churchill, but no lessening of either his vision, his commitment, or of the words he brought to bear to in support of both. Even though he was no longer prime minister, Churchill’s words were still essential to framing both the dangers of conflict and opportunities for peace vying for mastery in the postwar landscape.

A Leader of the Opposition, in August 1945, he warned the House of Commons:

“…The bomb brought peace, but men alone can keep that peace,

and henceforward they will keep it under penalties which threaten the survival,

not only of civilization but of humanity itself…”[12]

Churchill was an early, ardent, and vital advocate of pan-European integration. In 1946, he spoke at Zurich University promoting a United Europe. This speech that lent bold impetus to formation of what would eventually become the European Union. In a May 7th 1948 address to the embryonic Congress of Europe, Churchill said:

“We shall only save ourselves from the perils which draw near

by forgetting the hatreds of the past, by letting national rancours and revenges die,

by progressively effacing frontiers and barriers which aggravate and congeal our divisions,

and by rejoicing together in that glorious treasure

of literature, of romance, of ethics, of thought and toleration…

which is the true inheritance of Europe.”[13]

Amid the great events and dramatic utterances it’s easy to forget the whimsy and wit that balanced Churchill. Even in the darkest moments of the war, Churchill would often leaven his comments, his own mood, and the sense of the moment. This sense of light and sparkle even in darkness was physically manifest in Churchill’s love of painting. Of painting, Churchill wrote:

“I cannot pretend to feel impartial about the colours.

I rejoice with the brilliant ones, and am genuinely sorry for the poor browns.

When I get to heaven I mean to spend a considerable portion of my first million years

in painting, and so get to the bottom of the subject.

But then I shall require a still gayer palette than I get here below.

I expect orange and vermillion will be the darkest, dullest colours upon it,

and beyond them there will be a whole range of wonderful new colours

which will delight the celestial eye.”[14]

Churchill was undoubtedly a creature of extravagant confidence, sometimes bordering on hubris. But it was his perpetual sense of history that imparted a tempering humility and grace to his words.

For better or worse, Churchill lived long enough to become an icon. By the final years of his second premiership, he became “a living national memorial” of the time he lived and the Nation, Empire, and free world he served. Perhaps, after a life of strife and vigorous opposition, he enjoyed the accolades. But even these he accepted with his characteristic sense of the history with which his life had become entwined.

“I was very glad that Mr. Atlee described my speeches in the war

as expressing the will… of the whole nation…

It was a nation and race dwelling all round the globe that had the lion heart.

I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar.

I also hope that I sometimes suggested to the lion the right places to use his claws.”[15]

I realize that I’m not the only one with some regard for Churchill’s words. When Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953, here is what they said:

“In his great work about his ancestor, Marlborough, Churchill wrote ‘Words are easy and many, while great deeds are difficult and rare.’ Yes, but great, living, and persuasive words are also difficult and rare. And Churchill has shown that they too can take on the character of great deeds.”

The Swedish Academy also said: “There is something special about history written by a man who has himself helped to make it.”

They might also have said: Never in the field of human endeavor has so much history been written by one who made so much history.

Churchill wasn’t just prolific. He was a gifted writer with a distinctive voice. All of the sharp wit, incisiveness, rolling cadences, sweeping sense of history, and unusual foresight that marked his life permeate his writing.

Even so, history offers many prolific and talented wordsmiths. What sets Churchill apart?

Churchill’s extraordinary life is what so compellingly infuses both his writing and his enduring persona. Churchill doesn’t just tell a great story, he is a great story. Since most of what he wrote about were events and issues and people and places central to his life, Churchill’s words reinforce and perpetuate his singularity.

Often the writings of a great statesman are just a polished literary headstone, secondary to a life spent in pursuit and exercise of power. Churchill’s life was writing. He wrote before he achieved power. He wrote after power passed from his aging hands. Words were his personal currency and daily essential.

Of course he wrote for practical purposes. He wrote to sustain himself and his family. He wrote to persuade and influence and assert. But he also wrote as if words were not just a tool, but a compulsion, a part of him that he was driven to exhale onto page after endless page. During the course of his long life Churchill left on paper perhaps more published work – and more that was revealingly himself – than any other great statesman.

Leadership

So what did Churchill use all these words for?

Now we come to leadership.

Do you remember the unflattering quote I related earlier this evening? The one from Churchill’s letter to his mother, writing from Bangalore, India when he was a 23 year-old cavalry officer? To remind us, the young Churchill wrote: “I do not care so much for the principles I advocate as for the impression which my words produce & the reputation they give me. This sounds very terrible. But you must remember that we do not live in the days of Great Causes.”[16]

In this same letter, Churchill also wrote: “I think a keen sense of necessity of burning wrong or injustice would make me sincere…” Churchill had recently seen his first active service and had conspicuously distinguished himself on a bloody battlefield. He spoke of crying when he met a unit of his fellow soldiers who had become unsteady under fire and abandoned their young officer, who was killed as a result – quite “literally cut in pieces”. To Churchill’s credit, he cried both for the steadfast officer who fell and the faltering men who abandoned him. He closed his letter musing “…I believe that [in essence] I am genuine…” and tried to define the interplay between his head and his heart.

This very young Churchill was impetuous, insatiably ambitious, and unreasonably brave. He was flexing and experimenting with words, just as he was testing and proving his mettle. The “Great Causes” of which he spoke would find him. And find him ready.

Churchill’s words would ultimately shape him as much as they shaped the world he sought to engage and influence.

Churchill used words to encapsulate and project a vision not just of the world as he saw it, but the world as he wished it to be.

This is fascinating. For the twentieth century is full of leaders who imposed a rhetorical vision on their peoples, often to terrible effect. This is part of what makes Churchill so remarkable. Again, Isaiah Berlin best says what I wish to say:

With his words, Berlin said, Churchill showed a capacity “to find fixed moral and intellectual bearings, to give shape and character, colour and direction and coherence, to the stream of events.”[17]

“The Prime Minister was able to impose his imagination and his will upon his countrymen… [He lifted] them to an abnormal height in a moment of crisis…. it did turn a large number of inhabitants of the British Isles out of their normal selves and, by dramatizing their lives and making seem to themselves and to each other clad in the fabulous garments appropriate to a great historic moment… This is the kind of means by which dictators and demagogues transform peaceful populations into marching armies; it was Mr. Churchill’s unique and unforgettable achievement that he created this necessary illusion within the framework of a free system without destroying or even twisting it; that he called forth spirits which did not stay to oppress and enslave the population after the hour of need had passed.”[18]

It may be impossible to have a conversation about Churchill and leadership without discussing the Second World War. So I will steer into the curve.

I’ll talk about two things. First, Churchill’s stirring wartime eulogy of Neville Chamberlain early during the war and second, the history of the war Churchill wrote in its aftermath.

Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940. Throughout the 1930s he had sounded the alarm and both labored to avert the coming conflict, while also preparing his nation to prevail should it become unavoidable. We see the Second World War now as a dominant, irrevocable landmark in the geopolitical topography of the twentieth century. But in a world barely a generation away from the numbing, unspeakable carnage of the First World War, another such war seemed inconceivable. And those who prophesied readiness and resolve were shunned.

We see Churchill as the inevitable leader for the time. But at the time he was out of power and out of favor, reduced to appealing directly to the public through his writing and speeches, and to working indirectly through sympathetic allies in the bureaucracy and back benches of Parliament.

Indeed, it was the leadership of his own Conservative Party that was perhaps most responsible for ignoring and ostracizing Churchill.

Tall, elegant, and patrician, at home in wing collar with furled umbrella and with a reputation for being austere and dictatorial, Neville Chamberlain seemed a visual and political antithesis of Churchill. As Prime Minister in the late 1930s, Chamberlain famously intensified fruitless efforts to appease Nazi Germany as a means of avoiding the coming war – even as Churchill prophesied war as increasingly inevitable in the face of British military and political weakness. In late September, 1938, it was Chamberlain who signed the Munich Pact with Hitler’s Germany, conceding Czechoslovakia in return for an empty promise of “peace in our time.”

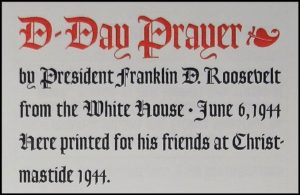

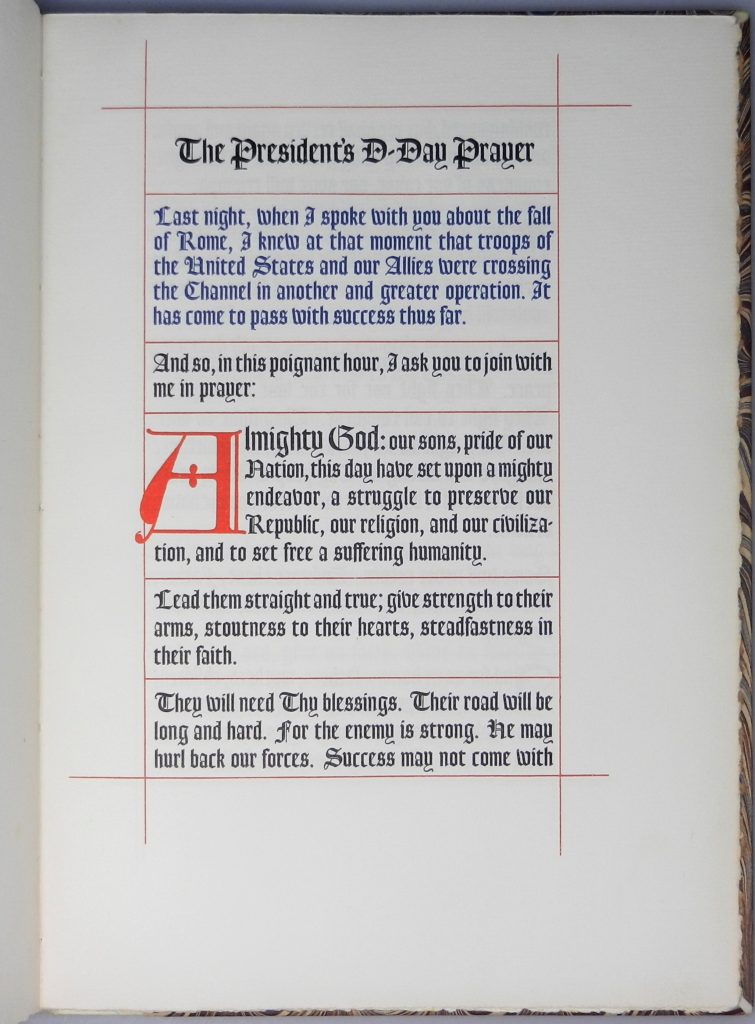

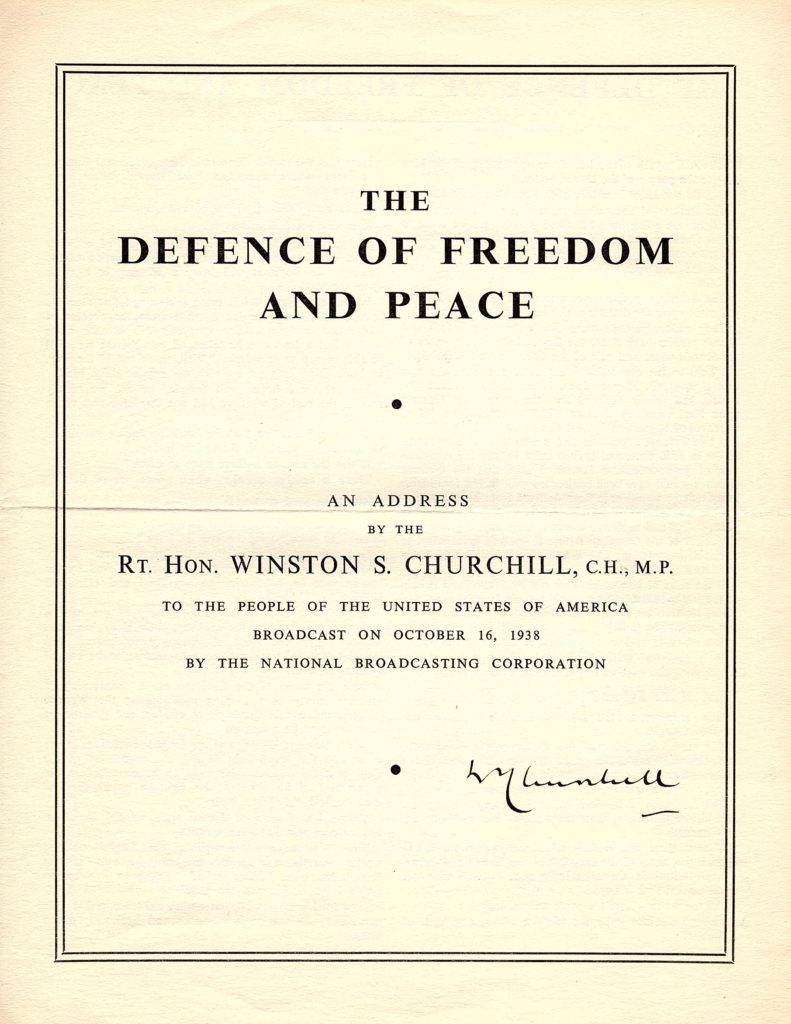

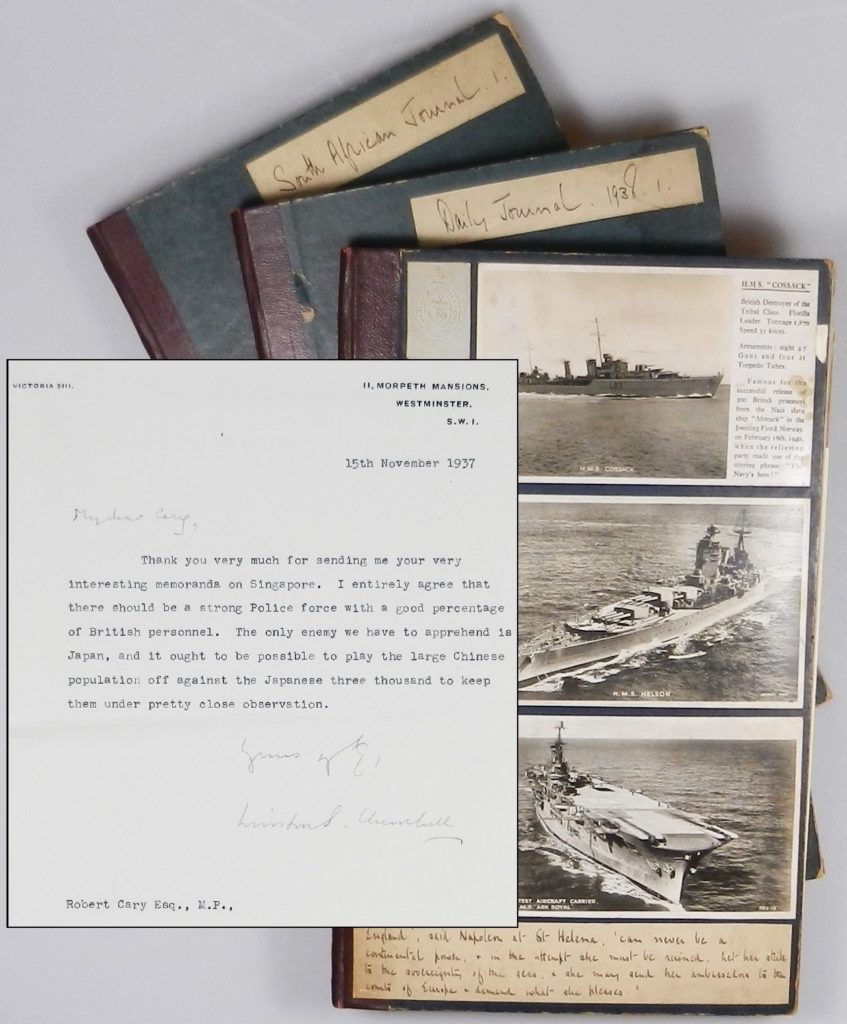

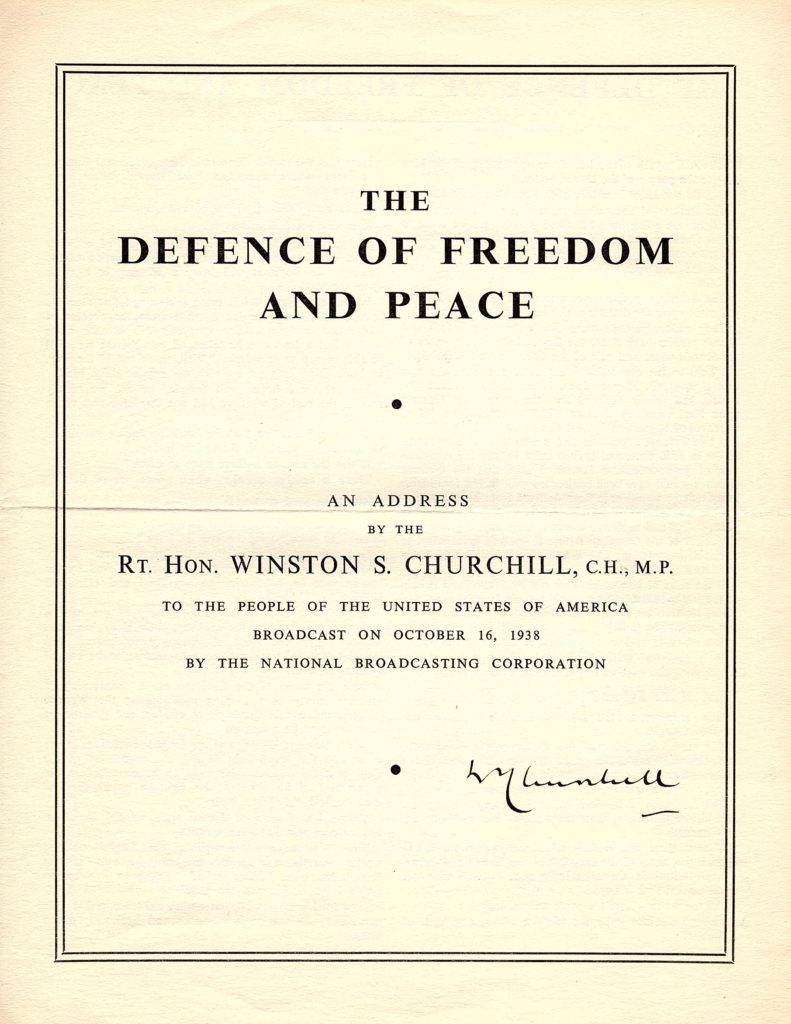

“The Defence of Freedom and Peace” – Churchill’s October 16th, 1938 broadcast address to the American people about the Munich agreement

Are you all OK with one last prop? I have 8 or 9 minutes of talking left, but I also have one more prop that will take a minute or so to present. It’s up to you… But I have to say that it is a pretty cool item.

OK?

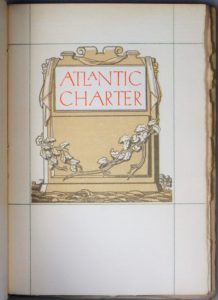

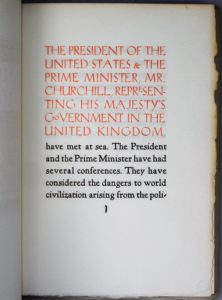

This is a textually unique, bibliographically unidentified edition of Churchill’s October 16th, 1938 broadcast address to the American people about the Munich Agreement.

This is a textually unique, bibliographically unidentified edition of Churchill’s October 16th, 1938 broadcast address to the American people about the Munich Agreement.

It may seem odd that Churchill – merely a Member of Parliament and representative of neither his Party nor his Government – would address the people of the United States. The fact is that Churchill’s tireless campaigning for prudent rearmament and collective security had given him an independent voice and audience. And Chamberlain’s Munich concession to Hitler turned Churchill’s long running disagreement with Chamberlain into an open breach. So by this time, it was almost as if Churchill was Leader of the Opposition, despite sharing the party of the sitting Prime Minister.

Churchill used his personal platform to appeal directly to the American people with a strikingly blunt assault on the moral and strategic infirmity of the Munich agreement and a clarion call for preparedness.

No other contemporary stand-alone publication of this speech is known. This pamphlet is definitively contemporary, evidenced by accompanying Chartwell stationery printed: “19th November 1938 | With Mr. Churchill’s compliments.” Moreover, it is boldly signed by Churchill on the front cover. But most interesting is the fact that this pamphlet appears likely to have been printed from a late-stage version of Churchill’s speech notes prior to delivery of the speech.

Churchill is known to have made emendations and revisions to his speeches up until the final moments preceding delivery – including this specific speech.

Courtesy of The Churchill Archives Centre, we reviewed Churchill’s original hand-corrected speech notes. We found a number of Churchill’s personal emendations to the speech as delivered which are not incorporated into this printed pamphlet. Most significant is the conclusion. A substantial five-sentence passage – essentially the “hard-sell” to the American people, beginning with the line “Far away, happily protected by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, you, the people of the United States…” – appears as the final paragraph in this pamphlet. But this critical paragraph was relocated closer to the mid-point of the speech when delivered.

This pamphlet is not just an amazing collectible item, but a tangible reminder of how very personally Churchill grappled with the words he bent to his purpose.

Not until Hitler invaded the Low Countries and France did Chamberlain lose the confidence of the House of Commons – and lose 10 Downing Street to Churchill.

But Churchill kept him on in the government. The two men worked with shared purpose until cancer forced Chamberlain’s resignation.

On November 12th, 1940, at the height of danger for Britain, Churchill eulogized Chamberlain in the House of Commons. Churchill said:

“The only guide to a man is his conscience; the only shield to his memory is the rectitude and sincerity of his actions… we are so often mocked by the failure of our hopes and the upsetting of our calculations; but with this shield, however the fates may play, we march always in the ranks of honour.”

“Whatever else history may or may not say about these terrible, tremendous years, we can be sure that Neville Chamberlain acted with perfect sincerity according to his lights and strove to the utmost of his capacity and authority… to save the world from the awful, devastating struggle in which we are now engaged. This alone will stand him in good stead as far as… the verdict of history is concerned.”

As a piece of moving oratory, for my money Churchill’s eulogy of Chamberlain stands beside the famous funeral oration of Pericles from fifth century B.C. Athens. What most distinguishes it is perhaps a tremendous humanity and humility. Humanity in the sense of a generosity of spirit, a comprehending empathy. And in so clearly recognizing decency in the midst of tragic error, a fundamental humility of intellect and sentiment. This from a man not often recognized for humility.

We see these essential qualities of a comprehending humanity and humility threading the war and its aftermath, and indeed even the earliest years of Churchill’s political life and thought.

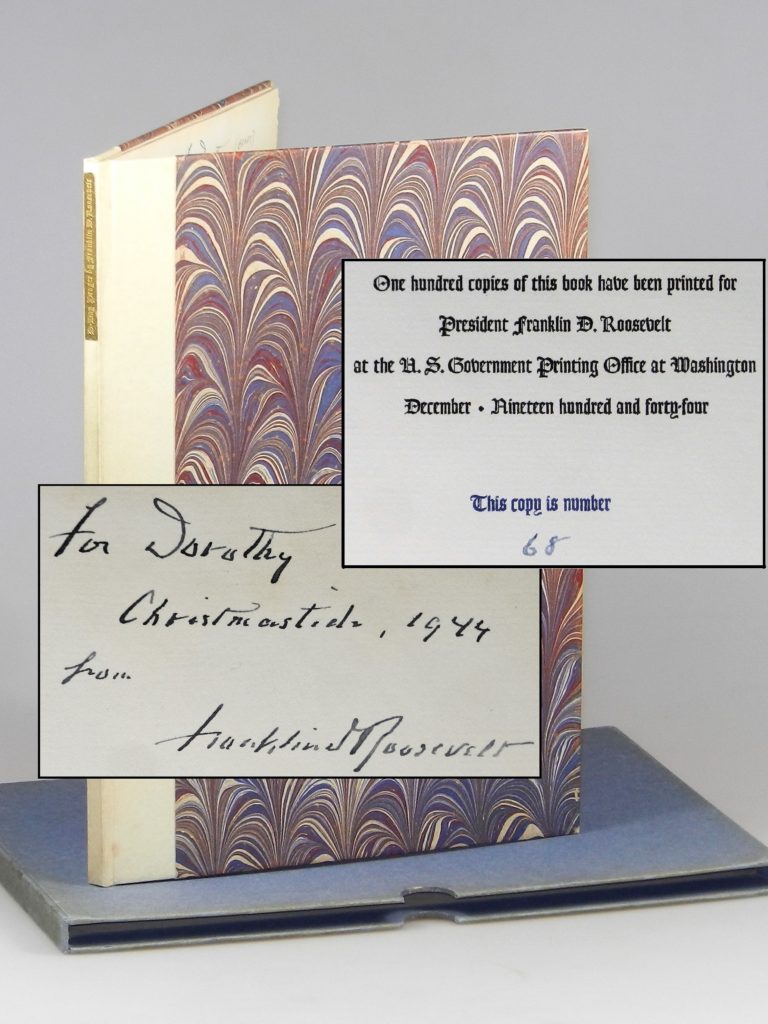

Of course when Churchill was done making history, he felt compelled to write it. His six volume history of the Second World War was published between 1948 and 1953.

Perhaps nothing makes the intensely, inevitably personal nature of Churchill’s history of the war more clear than his “Moral of the Work.”

When Volume I was published in 1948, Churchill put his “Moral of the Work” prominently and alone on the page immediately following the author’s Acknowledgements.

It reads, simply:

“In War: Resolution

In Defeat: Defiance

In Victory: Magnanimity

In Peace: Goodwill”

Let me read that again:

“In War: Resolution

In Defeat: Defiance

In Victory: Magnanimity

In Peace: Goodwill”

The boy who had professed not to care so much for principles more than 50 years earlier on the battlefields of colonial India had very much clarified his moral framework. In a cynical post-war world slipping inexorably into a new Cold War, perhaps some considered it banal – or at least overly simplistic – to ascribe a moral to the greatest conflict the world had yet seen. Churchill did not.

Likely better than most, he well understood the often senseless and bloody chaos and vagaries inherent to the human condition. Precisely “because we are so often mocked by the failure of our hopes and the upsetting of our calculations” did he recognize the vital role of purposeful resolve, reasoned defiance, and generous decency in public affairs – of that “rectitude and sincerity” in personal conduct for which he eulogized Neville Chamberlain..

The “Moral” testifies to both Churchill’s own statecraft and to the failures of statecraft that precipitated the Second World War and would unfortunately persist in its wake.

The words also trace a vital arch underpinning Churchill’s political thought and character and spanning his public life. The guiding sentiments encapsulated by the “Moral” allowed Churchill – for all his reputed pugnacity – to achieve farsighted perspective and bridge material, empathetic, and intellectual differences throughout his long life.

As early as 1906, Churchill expressed his thought in similar terms. In March of that year, he told the House of Commons: “As we have triumphed, so we may be merciful; as we are strong, so we can afford to be generous.”[19]

According to Churchill’s Private Secretary, Eddie Marsh, Churchill first composed what became his “Moral of the Work” soon after the First World War as an “epigram on the spirit proper to a great nation in war and peace.”[20] Churchill was asked to devise an inscription for a war monument in France. He submitted exactly the same words that would become the “Moral of the Work” in his history of the Second World War. It is deeply sad that the inscription was not accepted.[21] The rejection is, in fact, a perfect commentary on the failures of the victors to secure the post-WWI peace, thus ultimately precipitating the Second World War that followed.

Churchill “had seen the danger of another war with Germany even before the first had entered its final phase. In articles published in both America and Britain during 1917, he insisted even then on far-reaching efforts to meet those German demands that were justifiable.”[22]

On November 23rd, 1919, only a year after Armistice Day and certainly long before the bitter sentiment of the victors had faded, Churchill wrote in the Illustrated Sunday Herald:

“The reconstruction of the economic life of Germany

is essential to our own peace and prosperity.

We do not want a land of broken, scheming, disbanded armies, putting their hands to the sword because they cannot find the spade or the hammer.”

Churchill’s warnings would be substantially ignored by the victors. Fourteen years later a defeated and desperate Germany would elect Adolph Hitler.

Churchill’s moral and pragmatic consistency as a statesman did not waver. In September 1946, in the wake of the war in which he was perhaps Germany’s most implacable foe, Churchill told assembled European leaders:

“The first step in the re-creation of the European family

must be a partnership between France and Germany…

There can be no revival of Europe without… a spiritually great Germany.”[23]

It is interesting to note that many have criticized Churchill for moral flexibility, for changing his fundamental tenets and principles over time to suit circumstance. Superficially, one can see how such a view proliferated.

First, he was in public life for a tremendously long time – allowing him to participate in an incredible variety of public decision, including two world wars.

Second, he was a strong personality, attracting a considerable variety and intensity of detractors over time. But, as evidenced by the decades of consistent political thought underpinning the Moral of the Work we just discussed, what is most remarkable about Churchill is not his malleability, but quite the opposite – his constancy.

Again, the scholar Isaiah Berlin said it better than I can. He wrote:

“It is the strength and coherence of his [Churchill’s] central, lifelong beliefs that has provoked greater uneasiness, more disfavor and suspicion… than his vehemence or passion for power or what was considered his wayward, unreliable brilliance…. No strongly centralized political organization feels altogether happy with individuals who combine independence, a free imagination, and a formidable strength of character with stubborn faith and a single-minded, unchanging view of the public and private good.”

In his portrait of Churchill, Berlin wrote that Churchill believed in a specific world order and that “the desire to give it life and strength is the most powerful single influence upon everything which he thinks and imagines, does and is. When biographers and historians come to describe and analyse his views on Europe or America, on the British Empire or Russia, on India or Palestine, or even on social or economic policy, they will find that his opinions on all these topics are set in fixed patterns, set early in life and only later reinforced.”[24]

My own words will be less eloquent than those of either Churchill or Isaiah Berlin. I would say that Churchill comprehended the broad sweep of history as few leaders before or since. History was not a curriculum he consulted or a weight he bore. It was a current to which he committed himself. Which he ruddered and rode. Navigated and became.

And words – a torrent of words – evocative, emotional, reasoning, reckoning – were his constant companion. Churchill’s words charted his course, gave polarity to his compass.

So again, why are we here tonight discussing this particular British prime minister?

Because he shows us what we can do. What we can do.

How we humans can strive and be magnificent, despite every failure, fault, and folly.

And he tells us in his own powerful, compelling words. There is no way to know this man better – to see him, our world, and ourselves the way that he saw – than to read his own words. So I commend Churchill’s words to you, and I thank you for inviting me speak with you this evening.

And he tells us in his own powerful, compelling words. There is no way to know this man better – to see him, our world, and ourselves the way that he saw – than to read his own words. So I commend Churchill’s words to you, and I thank you for inviting me speak with you this evening.

[1] Excerpt from “Painting as a Pastime” published in Strand Magazine, December 1921

[2] WSC to Lady Randolph, letter of 16 May 1898, Bangalore, Randolph S. Churchill, Companion Vol. I, Part 1 1874-1896

[3] R. Churchill, Companion Volume I, Part 2, p.1197

[4] November 10th, 1897 letter from Winston S. Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill posted from Bangalore

[5] December 22nd, 19897 letter from Winston S. Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill posted from Bangalore

[6] The Story of the Malakand Field Force, p.47

[7] The River War, Churchill reflecting on the Battle of Omdurman, Volume II, p.162

[8] For Free Trade, p.78

[9] My African Journey, Chapter I, p.1, opening lines

[10] Berlin, Mr. Churchill in 1940, p.12

[11] “Fifty Years Hence” first published in the November15th, 1931 issue of Maclean’s and the December 1931 issue of Strand Magazine, thereafter in Thoughts and Adventures, p.279

[12] Speech as Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons, August 16th, 1945

[13] Speech of May 7th, 1948 to the Congress of Europe

[14] Painting as a Pastime, p.24-25

[15] Remarks of November 30th, 1954

[16] WSC to Lady Randolph, letter of 16 May 1898, Bangalore, Randolph S. Churchill, Companion Vol. I, Part 1 1874-1896

[17] Berlin, Mr. Churchill in 1940, p.12

[18] Berlin, Mr. Churchill in 1940, pp. 29-30

[19] March 21st, 1906 speech in the House of Commons

[20] Marsh, A Number of People, p.152

[21] My Early Life, p.346

[22] Woods, Artillery of Words, p.86

[23] Speech of September 19th, 1946 at Zurich University advocating pan European integration to the embryonic Council of Europe

[24] Berlin, Mr. Churchill in 1940, pp.16-17

This February 1950 photo features Winston S. Churchill striding arm-in-arm with his daughter-in-law, June, and son, Randolph, in the constituency Randolph would lose that month to future Labour Leader Michael Foot.

This February 1950 photo features Winston S. Churchill striding arm-in-arm with his daughter-in-law, June, and son, Randolph, in the constituency Randolph would lose that month to future Labour Leader Michael Foot.