Recently we were privileged to acquire a truly singular copy of the U.S. first edition of the first volume of Churchill’s war speeches. This copy is signed by fifty-one individuals, including the former King of England, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, Clementine Churchill, a who’s who of British Wartime leadership, and dozens of wartime pilots of the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and Royal Air Force (RAF) who piloted the aircraft bearing these and other British leaders during and following the Second World War.

We are pleased to offer this book for sale. However, the story of this remarkable book is far too long to tell in a simple listing description. And it is a story we just have to tell. So we are writing about this wonderful book in this *very* long blog post, complete with dozens of images. We hope you enjoy learning about this book as much as we have.

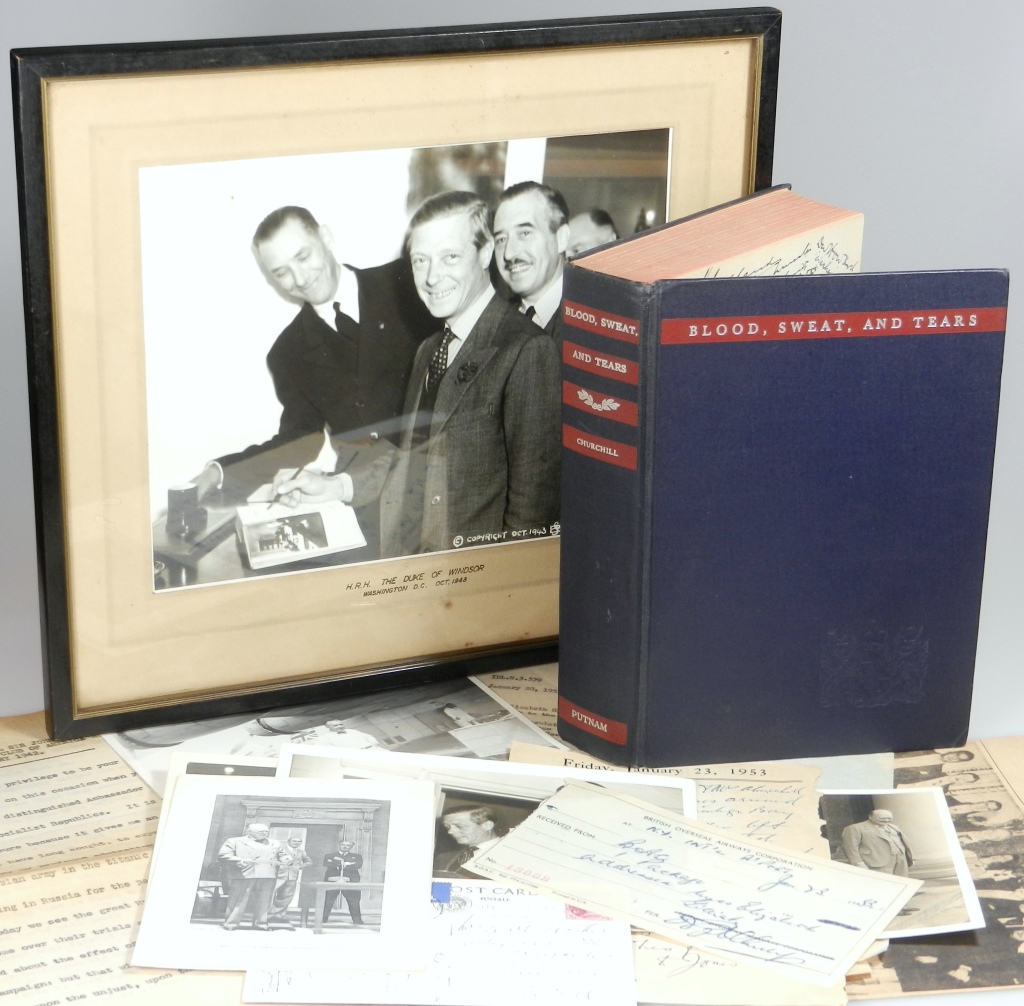

The signed book is accompanied by a framed photo of former King Edward signing this very book, as well as a number of documents attesting to provenance, including vintage photographs and newspaper clippings, correspondence, notes, a calendar page, and a receipt.

We provide an extensive description of the book, its provenance, and its accompanying documents, as well as biographic information on each of the noteworthy signatures identified.

The signatures

There are a total of fifty-one signatures on four different pages within the book. Among them we have identified thirteen noteworthy wartime figures. Presumably many of the remainder are BOAC pilots. Likely there are more as-yet undeciphered names of historic significance among the fifty-one.

The earliest dated signature is December 1941, the month of the attack on Pearl Harbor and formal entry of the United States into the Second World War. Correspondence accompanying the book indicates the final signature occurred in January 1953.

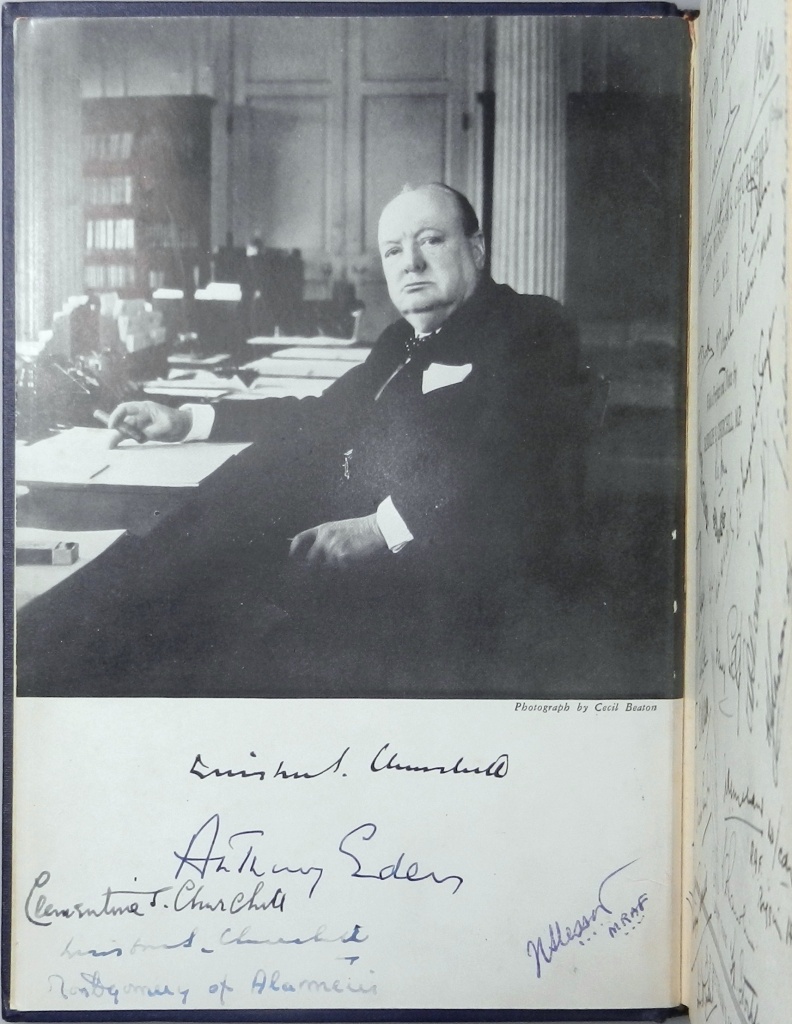

On the frontispiece:

- Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, Prime Minister 1955-1957

- Baroness Clementine Ogilvy Spencer-Churchill

- Sir Winston S. Churchill, Prime Minister 1940-1945 & 1951-1955

- Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount of Alamein

- Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir John Cotesworth Slessor

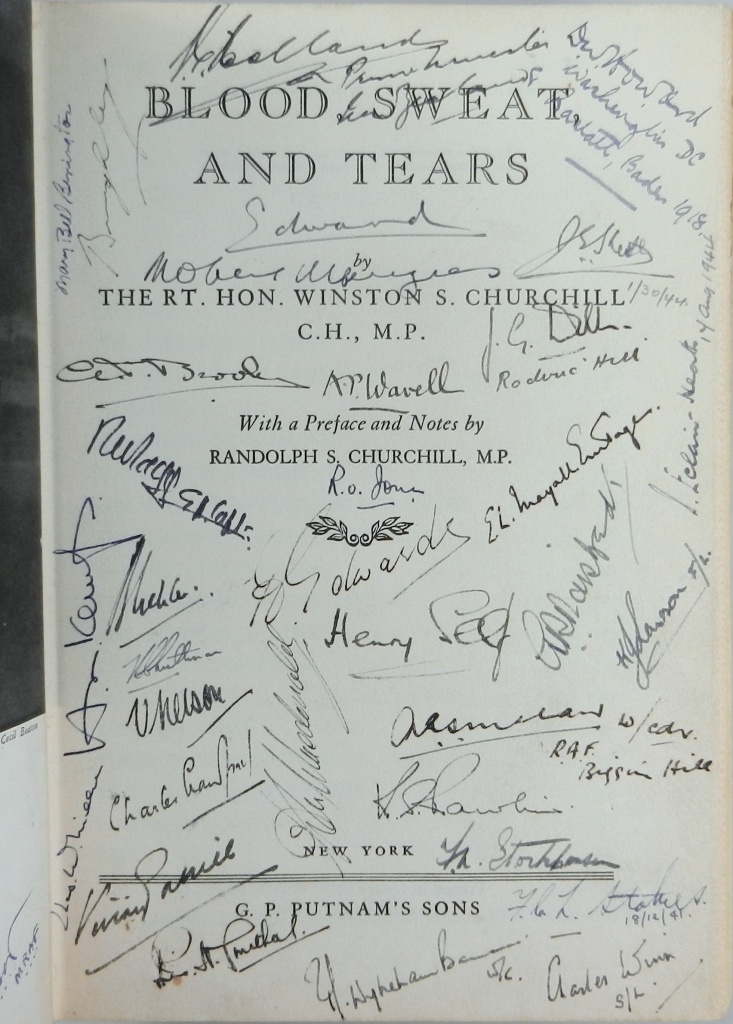

On the title page:

- Former King Edward VIII, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor

- Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke

- Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, Viceroy of India

- Field Marshal Sir John Greer Dill

- Air Marshal Sir Roderic Maxwell Hill

- Air Marshal Sir Robert Owen Jones

- Sir Albert Henry Self

- Colonel Sir Edmund Vivian Gabriel

- Twenty three additional signatures, one dated December 1941, two dated 1944, many, if not all, ostensibly those of pilots.

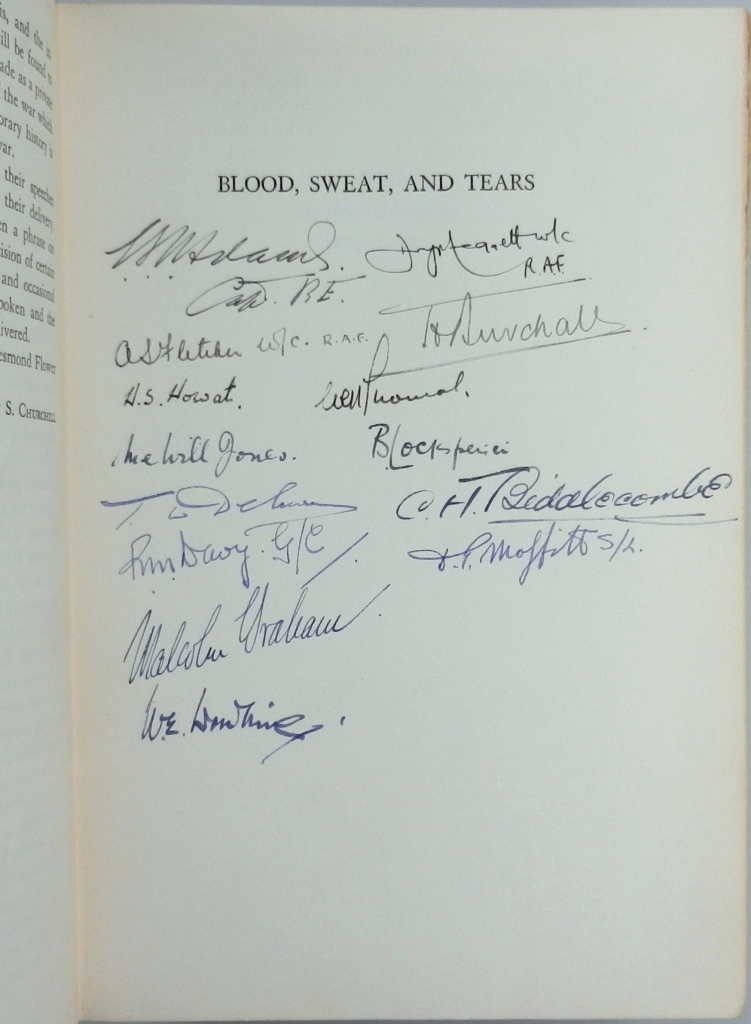

On the second half-title, following the Introduction:

- Fourteen signatures, ostensibly those of pilots, two specifying “R.A.F.”

On the rear pastedown:

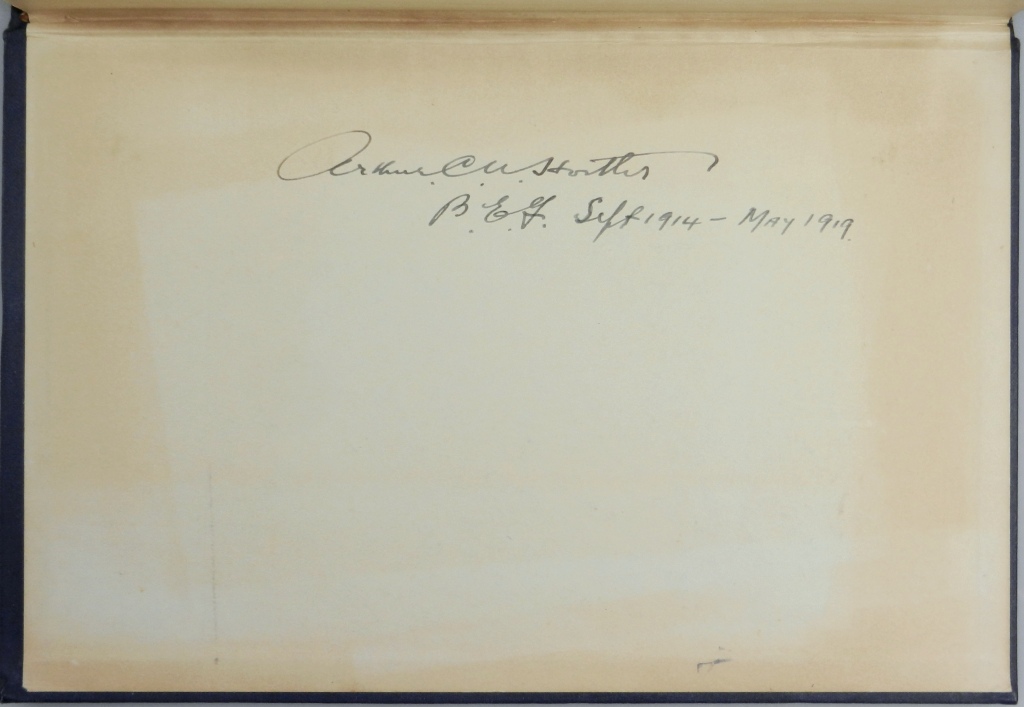

- Arthur C. V. Hostler, with “B.E.F. Sept 1914 – May 1917.” directly below in the same hand. Ostensibly, “B.E.F.” is British Expeditionary Force, indicating Hostler’s service in the First World War.

Collection of the signatures

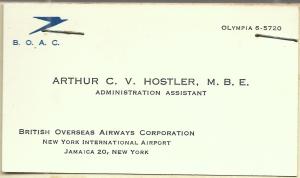

Arthur C. V. Hostler, M.B.E. (Civil Division, appointed 18 December 1945) was the original owner of this book and collected the remarkable array of signatures therein. Hostler was in a special position to be in contact with such a great number of wartime leaders and pilots.

During the Second World War, Hostler was a member of the British Air Commission, serving the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) in Washington D.C. The British Air Commission delegation to Washington was charged with arranging purchase of American aircraft and aircraft components to fulfill Royal Air Force needs.

After the War, Hostler was employed by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) in New York. The BOAC was formed in 1939 and, throughout the Second World War until 1946, was the nationalized airline of Great Britain. BOAC operated under the direction of the Secretary of State for Air, with no requirement to act commercially. After the War, between 1946 and 1974, BOAC operated all long-haul British flights. Hence, during the Second World War and for a number of years thereafter, it was common for British civil and military leaders to travel on BOAC flights.

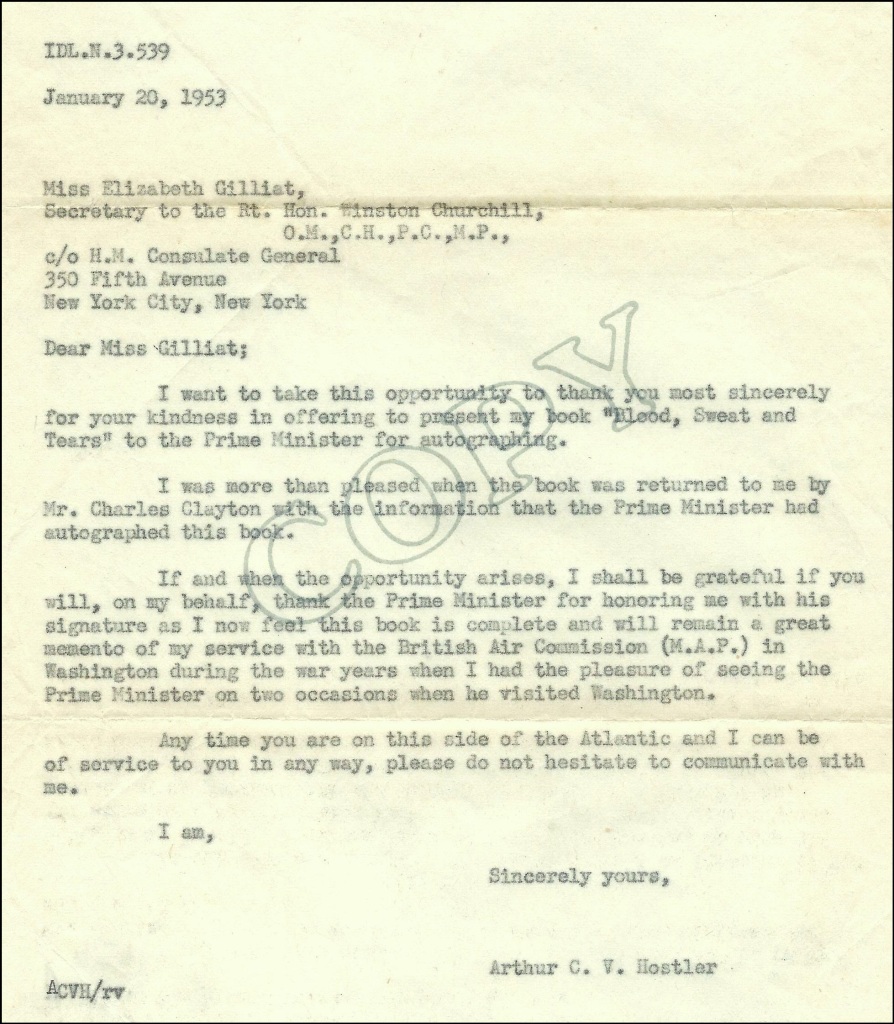

Hostler’s BOAC business card is stapled to the front free endpaper. The documents accompanying the signed book include a copy of a 20 January 1953 letter from Hostler to Elizabeth Gilliat, Secretary to Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill, thanking Ms. Gilliat for securing Churchill’s signature of the book. Hostler wrote:

Dear Miss Gilliat;

I want to take this opportunity to thank you for your kindness in offering to present my book “Blood, Sweat and Tears” to the Prime Minister for autographing.

I was more than pleased when the book was returned to me by Mr. Charles Clayton with the information that the Prime Minister had autographed this book.

If and when the opportunity arises, I shall be grateful if you will, on my behalf, thank the Prime Minister for honoring me with his signature as I now feel this book is complete and will remain a great memento of my service with the British Air Commission (M.A.P.) in Washington during the war years when I had the pleasure of seeing the Prime Minister on two occasions when he visited Washington.

Anytime you are on this side of the Atlantic and I can be of service to you in any way, please do not hesitate to communicate with me.

I am,

Sincerely yours,

Arthur C. V. Hostler

Indications are that the book was signed in January 1953 during Churchill’s visit to the United States and Jamaica via a request made by Hostler to Miss Gilliat. See further documentation below.

Documents accompanying the book

In addition to the copy of the letter to Churchill’s Secretary, documents accompanying the book include the following:

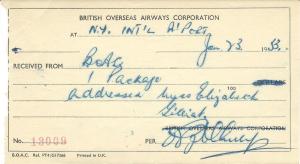

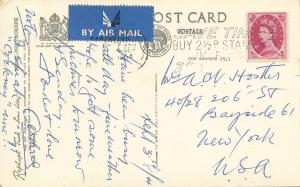

- A British Overseas Airways Corporation receipt originating at “N.Y. Int’L A’port” and dated “Jan. 23 1953” for the letter sent to Churchill’s Secretary, Elizabeth Gilliat.

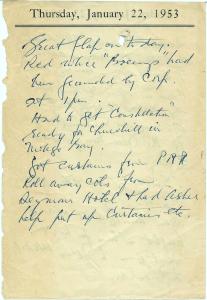

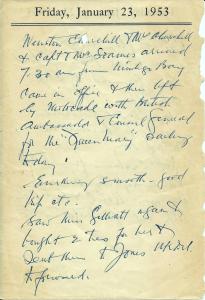

- A double-sided daily journal page apparently in Hostler’s hand from Thursday , January 22 and Friday, January 23, 2953, reading in part:

[Thursday, January 22, 1953] “…Had to get “Constellation” | ready for Churchill in | Montego Bay. | Got curtains from [indecipherable] | Roll away cots from | Seymour Hotel & had Asher | help put up curtains, etc.

[Friday, 23 January, 1953] “Winston Churchill & Mrs. Churchill | & Capt & Mrs. Soames arrived | 7:30 am from Montego Bay. | Came in office & then left by motorcade with British | Ambassador & Consul General | for the “Queen Mary” sailing | today. | Everything smooth – good | trip etc. | Saw Miss Gilliatt again & | bought [indecipherable] for her & | sent them to Jones [indecipherable] | to forward.”

Note: Churchill left Britain aboard the Queen Mary on December 31, 1952, accompanied by his wife, daughters Sarah and Mary as well as Mary’s husband, and Sir Roger Makins, newly appointed ambassador to Washington. Queen Mary docked in New York on the morning of January 5, 1953. By January 7, 1953 Churchill was in Washington to meet with Secretary of State-designate John Foster Dulles. On January 8, 1953 Churchill departed Washington on a flight (presumably BOAC) to Jamaica. On the morning of January 23, 1953, Churchill departed Montego Bay for New York via another BOAC flight (referenced in the calendar page above) for New York, departing that afternoon on the Queen Mary.

- A September 3, 1954 postcard (picturing Churchill in regalia) from Hostler to his wife, Alice.

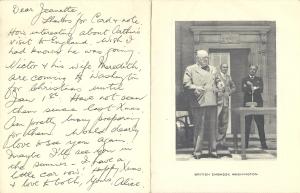

- A 1954 Christmas card to “Jeanette” (Jeanette Hostler, wife of Arthur Hostler) from “Alice” (Alice Makins, nee Alice Brooks Davis) the wife of British Ambassador in Washington Roger Makins. The cover features a photo of Churchill and Sir Roger Makins at the British Embassy, Washington, taken on June 29, 1954, by “Leading Aircraftsman J. A. Davis.” The autographed note from Alice to Jeanette, apparently alluding to the trip on which Hostler’s postcard to Alice was sent, reads in part:

Dear Jeanette, | Thanks for the Card & note. | How interesting about Arthur’s | visit to England. Wish I | had known he was going….”

- A photograph of Hostler on a dock with a BOAC flying boat in the background. Inked on the back of the photo is: “B.O.A.C. | Baltimore | 1947 | A. C. V. Hostler.”

- A photo of Churchill on the Washington, D.C. British Embassy steps. Inked on the back of the photo is: “May 1943”. In pencil below is: “on Embassy steps | Wash DC”.

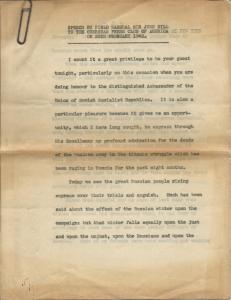

- A typed “Speech by Field Marshal Sir John Dill to the Overseas Press Club of America at New York on 26th February 1942.” The speech is 10 numbered pages, age-toned and brittle, fastened by a rusted and clearly contemporary paperclip that has stained the pages. Just two months prior Dill had been sacked as Chief of the Imperial General Staff by Churchill and narrowly escaped political exile by becoming head of the joint staff mission and senior British member of the combined chiefs of staff, as well as personal representative of the minister of defense, in Washington, D.C.

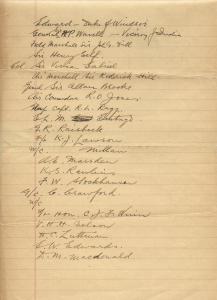

- A handwritten partial list on lined paper, apparently in Hostler’s hand, naming twenty-two of the fifty individuals who signed his copy of Blood Sweat and Tears

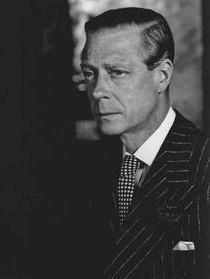

- A photograph of former King Edward VIII, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor, holding a book and flanked on the right by an unidentified figure in uniform and an unidentified civilian on the left. The back of the photograph is printed: “Photograph by | Sidney Barnett 1651 Fuller St. | Washington DC.”

- A photograph of former King Edward VIII, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor, speaking, flanked on either side by seated civilians. The back of the photograph is printed: “Photograph by | Sidney Barnett 1651 Fuller St. | Washington DC.”

- Various contemporary newspaper clippings.

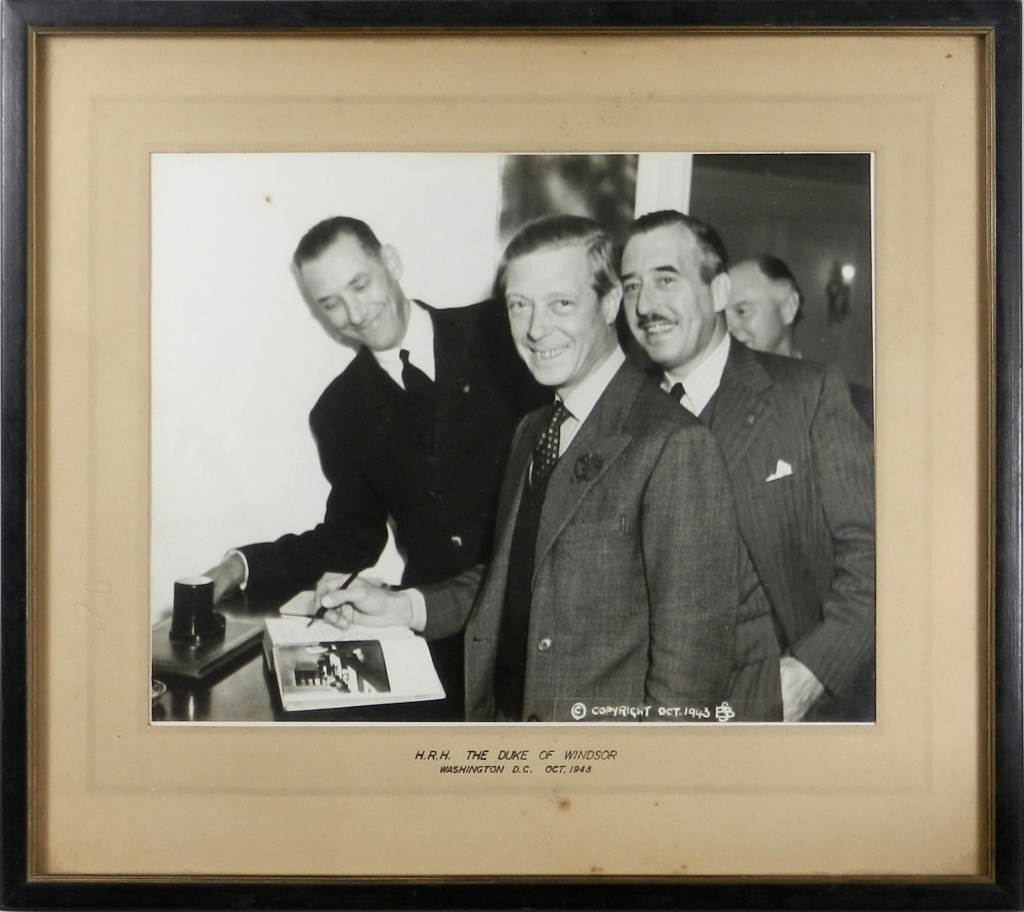

The framed photograph

Accompanying the book is a framed photograph of former King Edward VIII, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor signing this copy of Blood Sweat and Tears. Edward is centered in the photo, his right hand holding a pen and resting on the title page where he signed. The lower right of the photo states “copyright Oct. 1943” and the surrounding mat is hand captioned “H.R.H. The Duke of Windsor | Washington D.C. Oct. 1943.”

Both the title page and frontis page are visible, indicating that some of the title page signatures preceded that of Edward, while all of the frontis page signatures came later.

The matted photograph measures 9.25 x 7.25 inches. The sealed frame appears contemporary to the photograph and measures 13 x 11.75 inches. As indicated on the frame’s rear backing, the framing was done in Baltimore. The unexceptional frame is black wood with gilt inner edge, the mat tan.

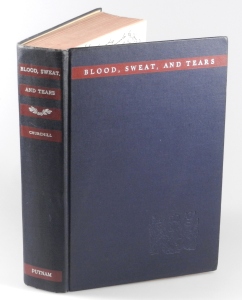

The edition

Blood Sweat and Tears is the first volume of Churchill’s famous war speeches, containing speeches from May 1938 when Churchill was still out of favor and out of power, to November 1940, six months after Churchill became wartime Prime Minister.

Between 1941 and 1946, Churchill’s war speeches were published in seven individual volumes. Of Churchill, Edward R. Murrow said, “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” In this first war speeches volume the great battle of the Twentieth Century and Churchill’s life begins.

In his first speech to Parliament as Prime Minister on 13 May 1940, Churchill stated plainly, as he had told his Cabinet earlier that day, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” This is the famous phrase from which the U.S. first edition takes its title. Published in England as “Into Battle”, this is one of the few Churchill first editions for which the U.S. edition bears a different title than the British.

The U.S. first edition is bound in smooth navy cloth with red banners and silver print and red-stained top edge in the same style as the preceding U.S. first editions of Great Contemporaries (1937), While England Slept (1938), and Step By Step (1939), with the addition of the Marlborough arms stamped in blind on the front cover, lower right.

Bibliographic reference: Cohen A142.3, Woods/ICS A66(b.1), Langworth p.207

Condition of the Book

Condition of the book is very good, impressive given that it was handled and signed by fifty-one individuals over more than a decade. The binding remains square and unfaded, with only minor wear to extremities and trivial scuffing to the lower spine.

The contents remain bright with no spotting. The front free endpaper is twice stapled at the top, securing Hostler’s BOAC business card and we note what appears to be glue staining (but no scarring) to a rectangular section below the business card, perhaps where a previous bookplate was affixed and fell off.

The rear pastedown shows differential toning, consonant with possible transfer browning from news clippings that may once have been laid in. The red-stained top edge is clean and uniformly sunned to dark pink. The untrimmed fore edge and the bottom edge are notably clean, showing only a hint of age-toning.

Biographies of non-BOAC signatories (in order of the appearance of their signatures)

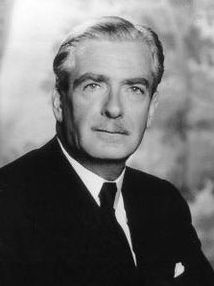

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon

Signature on the frontis page, centered below Churchill’s image

(1897-1977) Anthony Eden was Prime Minister from 1955-57, succeeding Winston Churchill. Educated at Eton and Christ Church Oxford, Eden served on the western front 1915-1918 and was awarded the Military Cross. He served as a Conservative Member of Parliament from 1923-1957. His posts included Parliamentary Under-Secretary, Foreign Office (1931-1933), Lord Privy Seal (1934-35), Minister for League of Nations Affairs (1935), and Foreign Secretary (1935-38, 1940-1945, and 1951-1955). Eden famously resigned his Foreign Secretary post on 20 February 1938 in protest to the Government’s appeasement policies. Of Eden’s resignation, Churchill wrote: “…on this night of February 20, 1938… sleep deserted me… There seemed one strong young figure standing up against long, dismal, drawling tides of drift and surrender, of wrong measurements and feeble impulses… he seemed to me at this moment to embody the life-hope of the British nation… Now he was gone.” (The Gathering Storm, pp. 257-8) Eden’s premiership, long-delayed while waiting for Churchill to relinquish the premiership, was fraught with challenge, including the Suez Crisis, and revealed Eden prone to reveal “irascibility, his inability at times to delegate, and his touchiness in the face of criticism.” Nonetheless, the passage of time sees Eden “increasingly recognized as a serious and patriotic figure who worked under the most appalling pressure for nearly three decades at the front line of British and world politics.” (ODNB) Eden was appointed a Knight of the Garter in 1954 and created 1st Earl of Avon in 1961. Many honors accrued to Eden, and he was an active chancellor of Birmingham University for nearly three decades.

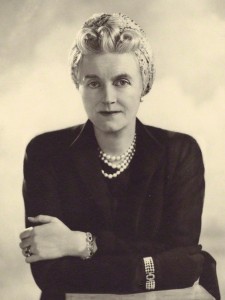

Baroness Clementine Ogilvy Spencer-Churchill

Signature on the frontis page, below and to the left of that of Anthony Eden

(1885-1977) Clementine Churchill, nee Clementine Hozier, was the wife of Winston S. Churchill. She first met Winston at a ball in 1904, where he made a poor impression. In March 1908 she was placed next to Winston at a dinner party, where he apparently made a better impression; they married on 12 September 1908. Their marriage brought five children: Diana (b. 1909); Randolph (b. 1911); Sarah (b. 1914); Marigold (b. 1918); and Mary (b. 1922). To their lifelong marriage Clementine brought “a shrewd political intelligence. She supplied balance to Churchill at two levels: her more equable nature ensured that she moderated the depth of his depressions, and her good judgment helped to ward off political mistakes.” (ODNB) Winston Churchill’s life and career were tumultuous and relentlessly eventful, so Clementine’s married life was perhaps inherently not without stress, challenges, and sadness. Nonetheless, their marriage appears to have been a truly effective and intimate partnership. “Throughout their married life, even if separated for only a few days, Clementine and Winston wrote spontaneous and informal letters to one another, intimately affectionate in tone, using their pet names Pug and Kat and reinforced with appropriate animal drawings.” (ODNB) ‘Marriage was her vocation’, said a newspaper leading article at her death (The Times, 13 Dec 1977) Clementine Churchill was appointed CBE (1918), GBE (1946), and created a life peer as Baroness Spencer-Churchill in 1965.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill

Signature on the frontis page bearing his portrait, below and slightly to the right of that of Clementine Churchill

(1874-1965) During his “remarkable and versatile” life, Winston Churchill played many roles worthy of historical note – member of Parliament for more than half a century, distinguished soldier and war correspondent, author of scores of books, ardent social reformer, combative cold warrior, painter, Nobel Prize winner. But more than anything else, it was Winston Churchill’s leadership during the Second World War that made him a preeminent historical figure. After passing out from Sandhurst he obtained his commission (20 February 1895) as a cavalry officer in the Queen’s Own Hussars. After an adventure in Cuba as a war correspondent, Churchill left England for India in 1896, where he would write his first book on the northwest Indian frontier, cementing the literary inclination that would become a financial, political, and expressive wellspring for the rest of his long life. Churchill would next fight and write in the Sudan, but it was via the Boer War in South Africa that the soldier and war correspondent made the seminal jump to politics. There, on 15 November 1899, Churchill was captured during a Boer ambush of an armored train. His daring escape less than a month later made him a celebrity and helped launch his political career. Churchill was first elected to Parliament in October 1900 as a Conservative. He would cross the aisle to become a Liberal in 1904, and by 1908, at age 33, become both a Cabinet Minister and a husband. By 1911 Churchill was first Lord of the Admiralty. In 1915, after the failure in the Dardanelles and the slaughter at Gallipoli, Churchill was made the scapegoat and forced to resign. At the onset of his first political exile at Hoe Farm in Surrey he discovered painting, which would be a passion and source of release and renewal for the remaining half century of his long life. He spent the balance of his political exile as a lieutenant colonel leading a battalion in the trenches. Before war’s end, Churchill was exonerated and rejoined the Government, a dramatic cycle of political ruin and rebirth that echoed the 1930s to come. In October of 1924 Churchill rejoined the Conservatives, elected to the Epping seat he would hold for the next 40 years, and joining the Conservative Government as Chancellor of the Exchequer. By the early 1930s, Churchill was beginning a decade out of power and out of favor that would be known later as his “wilderness years” substantially characterized by Churchill’s “unceasing struggle in the face of resentment, apathy, and complacency” as he criticized British foreign policy and warned prophetically of the coming danger posed by Nazi Germany. When war came, Churchill was recalled to the Admiralty in September 1939 and became Prime Minister in May 1940. Churchill would remain wartime Prime Minister until July 1945 and then serve as Leader of the Opposition until his second and final premiership from October 1951 to April 1955. In the course of a lifetime Churchill was the recipient of thirty-seven orders, decorations, and medals. He was made a Companion of Honour in 1922, awarded the Order of Merit in 1946, and the Order of the Garter in 1953.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount of Alamein

Signature on the frontis page, directly below that of Winston Churchill

(1887-1976) Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, KG, GCB, DSO, PC passed through Sandhurst “without distinction but without difficulty also” and began what would be fifty years in the British Army, serving in India from 1908 to 1913. “It was the First World War that changed Montgomery from a bumptious, querulous infantry subaltern, constantly at odds with authority, into a decorated company commander, outstanding staff officer—and trainer of men.” The First World War showed Montgomery ‘that the whole art of war is to gain your objective with as little loss as possible.’ This edict made Montgomery “the outstanding British field commander of the twentieth century.” (ODNB) Montgomery earned his fame in North Africa during the Second World War. In August 1942, Churchill gave Montgomery command of the Eighth Army, where Montgomery famously beat Rommel and oversaw defeat of Axis forces in North Africa. He went on to command the Eighth Army in Sicily and Italy, and Allied ground forces during Operation Overlord. After the war he would rise to Chief of the Imperial General Staff and be elevated to Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. He retired in 1958 as deputy commander of NATO’s European forces. The arrogant, outspoken, and politically inept Montgomery seldom missed either controversy or an opportunity for self-promotion. During the war he was often criticized by Allied commanders for his caution and slowness to strike. Uncharitable accusations made in Montgomery’s postwar memoirs lost him the friendship of President Eisenhower and forced Montgomery to publicly apologize to a fellow Field Marshal whom – ironically and perhaps hypocritically – he accused of being too slow to fight. Montgomery earned further criticism for declaring support for Apartheid after visiting South Africa, and for praising Chinese leadership after a visit to Mao’s communist China.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir John Cotesworth Slessor

Signature on the frontis page, lower right.

(1897-1979) Childhood Polio left John Slessor lame in both legs, but through the intervention of a family friend he was commissioned into the Royal Flying Corps on his eighteenth birthday, where he would spend a distinguished career. Described as “an officer of exceptional ability, charm, and force of personality”, Slessor “was one of that select group of officers who were clearly destined for the highest ranks of the air force.” (ODNB) Slessor held the critical post of director of plans at the Air Ministry from 1937 to 1940. He was appointed air commodore in 1939, air vice-marshal in 1941, air marshal in 1943, air chief marshal in 1946, and marshal of the Royal Air Force in 1950, retiring in 1953. Slessor was awarded the MC in 1916, appointed to the DSO in 1937, and created CB (1942), KCB (1943), and GCB (1948).

Edward VIII, Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor

Upper title page, centered between the title and author

(1894-1972) Edward, endowed with the forenames Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David and known to his family as David, was the first child of five sons and was thus groomed from the start to be king. Prince Edward “was early noted for charm and good looks.” He was also observed to be an “intelligent child, with something of his father’s prodigious memory and an innate, wide-ranging curiosity.” (ODNB)Edward was educated at Oxford. He left Oxford at the start of the First World War in 1914 and was commissioned in the Grenadier Guards, serving as vigorously as the imperative to prevent his death or capture would allow.After the war, “His easy manner and innovative hand-shaking sessions (he was the first royal to ‘press the flesh’ in the modern manner) made the prince a star in the Hollywood style then just emerging” and his popular appeal was enhanced by visits to Canada, the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, and India. (ODNB) The prince met Wallis Simpson (1896–1986) in the home of a then-mistress on 10 January 1931. Simpson was an American citizen married to her second husband, an American businessman then living and working in London. George V died on 20 January 1936 and the Prince of Wales was proclaimed as King Edward VIII. “He was a colourful figure in a drab era. Yet for all his modernity he had given little thought as to how he would behave as king… his ministers quickly realized that he was not seriously engaged in the processes of public business.” Moreover, “The king’s affair with Mrs. Simpson was undisguised… and his informal and sometimes arbitrary behaviour was the despair of his staff.” Neither did Edward enjoy the support of Prime Minister Baldwin’s government. By late 1936, the crisis posed by the King’s evident intention to wed the not-yet-divorced Simpson came to a head. Despite noteworthy intervention and support by Winston Churchill, the King abdicated on 11 December 1936, his reign having lasted just 327 days. In his broadcast that evening, now Prince Edward famously remarked: “You must believe me when I tell you that I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as King as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Edward married Simpson on 3 June 1937 and they remained married until his death in 1972. Edward enjoyed a comfortable life, if one substantially isolated from the Royal Family and occupied with less than the responsibilities he sought. “In asserting private before public priorities to the extent of occasioning a constitutional crisis, he undoubtedly went far beyond what the British and imperial establishment found acceptable in a sovereign… the Simpson affair was a symptom of a wider question mark which had arisen over his capacity to be king.” Nonetheless, Edward “behaved after 1936 with dignity and reserve in the face of what he and his wife saw as a deliberate and systematic exclusion.” (ODNB)

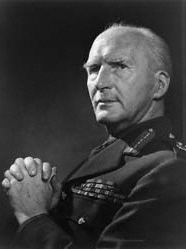

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke

Upper title page, directly below and left of the author’s name

(1883-1963) Alan Francis Brooke was born to a family with a centuries-long and distinguished record of military service to the crown and served as the foremost military advisor to Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the coordinator of British military efforts during the Second World War. At the apex of a distinguished and decorated military career, in December 1941, Brooke became chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) “in place of Dill, who had been no match for Winston Churchill. Soon thereafter Brooke became, in addition, chairman of the chiefs of staff committee and effectively the principal strategic adviser to the war cabinet as well as the professional head of the army.” (ODNB) When Brooke accepted Churchill’s appointment to serve as chief of the Imperial General Staff in November 1941, Churchill commented: “He is a combination of wisdom and vigour which I have found refreshing.” Churchill also had a personal connection with Brooke through “his two gallant brothers – the friends of my early military life”, Victor and Ronald. Victor was befriended by Churchill in 1895 and killed during the retreat from Mons in 1914; “Ronnie” was a comrade in arms and friend from the Boer War who also died prematurely in 1925. (Churchill, Their Finest Hour, pp. 233-4) By all accounts, Brooke proved a pivotal part of the British war effort, coordinating, commanding, consensus building, “and, often above all… contriv[ing] that Churchill’s indispensable and magnificent energies were not misdirected towards unsound and erratic strategic schemes.” (ODNB) Brooke was promoted to Field Marshal in 1944 and after the war handed over office to Montgomery, subsequently serving as Chancellor of Queen’s University, Belfast, holding various ceremonial posts, among them being nominated Lord High Constable of England and commander of the parade for the 1953 coronation of Elizabeth II, as well as holding director of numerous companies and engaging in philanthropic causes. In the First World War, Alanbrooke had been appointed to the DSO and had received the bar and six mentions in the dispatches. In 1940 he was appointed KCB, received the grand cross of both the Bath (1942) and the Royal Victorian Order (1953). He was created Baron Alanbrooke in 1945 and Viscount Alanbrooke in 1946, the year in which he was also created KG and admitted to the Order of Merit.

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, Viceroy of India

Upper title page, directly below the author’s name

(1883-1950) Archibald Percival Wavell was a career army officer who proved unfortunate in his commands during the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, despite enduring popularity with both the troops and the public. His early career included South Africa, India, and the First World War, followed by a decade divided between the War Office and staff during which he became known “as an officer untrammeled by convention.” As testimony to the point, “The general public came to associate him with a phrase he used in a lecture: that his ideal infantryman was ‘a successful poacher, cat-burglar and gunman’.” (ODNB) His first significant experience in a 30 year army career came in 1930. In command he became recognized “as an exceptional trainer of troops and a highly creative thinker.” The start of the Second World War found Wavell with the new command of the Middle East. A series of misfortunes not entirely attributable to Wavell’s leadership and competence eroded his position. When the decision was made to evacuate the British Somaliland protectorate (in Wavell’s absence), Churchill disapproved and Wavell defended it, beginning a permanent disaffection. After failure of British forces under Wavell in Greece and against Rommel, Churchill “lost confidence in Wavell” and he was replaced with Sir Claude Auchinleck, whose place Wavell took as commander in chief in India, a post Wavell held from 1941-1947. Here he also proved unlucky, nominated as supreme commander of the ill-fated American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) command of south-east Asia and the south-west Pacific. Nonetheless, in 1943 Wavell was promoted field marshal, appointed viceroy of India, and raised to the peerage as Viscount Wavell. As viceroy, Wavell “displayed considerable political acumen, sensitivity, and courage” but was severely hampered both by “lack of understanding from London” and political forces beyond his control. Wavell was eventually sacked, replaced by Mountbatten, who “rapidly concurred with Wavell’s diagnosis of the Indian situation” and “presided over the end of the raj” as Wavell had recommended. In his brief retirement before his death, Wavell was created Earl Wavell, indulged a love of literature, and served as chancellor of Aberdeen University. He received numerous decorations from many countries and in his own was appointed CMB (1919), CB (1935), KCB (1939), GCB (1941), and GCSI and CGIE in 1943, the same year in which he was sworn of the privy council.

Field Marshall Sir John Greer Dill

Upper title page, directly below and right of the author’s name

(1881-1944) Sir John G. Dill was Churchill’s first wartime chief of the Imperial General Staff and later head of the British joint staff mission in Washington, maligned for the former role and much praised – at least in America – for the latter. Dill, orphaned at the age of twelve, came from a long line of Dill scholars and ministers. A career military officer, he was commissioned in 1901. His early career seemed to emphasize his character and limitations more than his abilities; “At Sandhurst his conduct was exemplary, his marks uniformly mediocre. Worthiness outbid distinction.” (ODNB) It was a combination of the Staff College and the First World War that launched Dill’s career. He began the First World War as a captain and ended as a temporary brigadier. After the war he became an instructor and commandant at the Staff College and Imperial Defence College, ironically “attracting the epithet ‘intellectual'” as well as a reputation for vigor and drive. (ODNB) It is probable that the onset of the aplastic anaemia which killed him caused a decline in his vigor in the 1930s, even as he faced growing responsibilities. When he was appointed chief of the Imperial General Staff in April 1940, “he was in no condition to do what was both necessary and desirable; that is, stand up to Churchill at home and Hitler abroad.” (ODNB) Churchill called him ‘Dilly-Dally’ and Dill was replaced by his protégé, Brooke, in December 1941. When he was sacked, Churchill intended that he be sidelined as governor of Bombay. However, in December Churchill departed in haste for Washington to confer with Roosevelt after Pearl Harbor and took Dill with him. Dill stayed on in Washington, becoming “not only head of the joint staff mission and senior British member of the combined chiefs of staff, but also, ironically, personal representative of the minister of defence, an office claimed by Winston Churchill himself.” Here Dill distinguished himself and proved crucial as a trusted “guarantor and mediator, fixer and broker”. (ODNB) When his statue was erected in Arlington National Cemetery (a singular honor for a foreigner) the indispensible U.S. army chief of staff General George C. Marshall said of Dill: “He was my friend… my intimate associate through most of the war years… I have never known a man whose high character showed so clearly…” Dill was made KCB in 1937 and GCB in 1942 and, when he died in November 1944, was accorded a memorial service at Washington Cathedral, with the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff as his honorary pall bearers.

Air Marshall Sir Roderic Maxwell Hill

Upper right title page, below the author’s name and directly below the signature of Sir John G. Dill

(1894-1954) Unlike many of his military contemporaries, Roderic Hill did not begin with the intention of a military career, but studied to become an architect. However, fascination with flying ultimately drew Hill’s attention, and the diversion was cemented when Hill enlisted in the ranks at the outbreak of the First World War. Wounded and mentioned in the dispatches, Hill joined the Royal Flying Corps and by July 1916 had earned his wings. Hill swiftly became known for “his energy, enthusiasm and skill, and calculated daring as a pilot.” He ended the First World War as a squadron leader with the newly formed Royal Air Force and from 1917 to 1923 oversaw the experimental flying department of the royal aircraft factory at Farnborough. In 1936 Hill received his first senior command, working closely with the army under generals Dill and Wavell. By 1939 he was an air vice-marshal, but he nonetheless characteristically managed to fly the new advanced fighters, the Hurricane and the Spitfire. To Hill’s chagrin, his early war years included non-operational command posts. In 1941 Hill was controller of technical services with the British air commission in the United States and, among other things, played a role in persuading the Americans to make far greater provision for armament, including gun-turrets, in their heavy bombers than they had originally intended. Hill was subsequently commandant of the RAF Staff College in 1942-3. It was only in 1943 that he received the fighter group command he wanted. “So successful was he that only four months later Hill became air marshal commanding air defence of Great Britain, with the main task of defending Britain from German air attack while the Allied invasion of the continent was being prepared.” (ODNB) Here Hill made an impressive impact. When the first flying bombs were launched in June 1944, Hill boldly – and with full knowledge that he would be held responsible for the outcome – initiated “a complete redeployment and segregation of defences” which ultimately “saved London from a far worse bombardment than it received.” In the final year of the war Hill became Air Council member for training and, after the war, principal air aide-de-camp to the king. His final post was as Air Chief Marshal for technical services, after which he retired to become rector of the Imperial College of Science and Technology. Hill was appointed MC (1916), AFC (1918), CB (1941), and KCB (1944).

Air Marshal Sir Robert Owen Jones

Title page center

(1901-1972) Robert Owen Jones spent his career in the Royal Air Force, beginning as aircraft depot staff in India in 1925, rising to attend the RAF Staff College in 1934, and assuming his first commands thereafter in the mid 1930s. He was transferred to the Technical Branch in 1940 and later served as Head of the RAF delegation to Washington, D.C. After the Second World War, Jones successively served as Head of Planning Staff at the Air Ministry, Air Officer Commanding No 24 (Training) Group, and Controller of Engineering and Equipment, rising to Air Marshal. Jones was appointed AFC (1939), CB (1944), and KBE (1953).

Sir Albert Henry Self

Title page, lower center

(1890-1975) Albert Henry Self was a British civil servant. Before and during the Second World War he arranged purchase of American aircraft to fulfill Royal Air Force needs, serving as Director General of the British Air Commission. After the Second World War he held the post of Deputy Chairman in the Ministry of Civil Aviation. Perhaps most notably, Sir Henry Self played a significant role in development of the ubiquitous, essential, and iconic P-51 Mustang fighter. With the outbreak of war in 1939, the British established a purchasing commission to acquire American-produced aircraft. Self initially sought out North America to produce the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. It proved more workable to achieve design and production of a superior fighter than to transition North American’s assembly lines to the P-40. This swiftly resulted in production of the P-51 Mustang. The first production aircraft flew in May 1941 and the Mustang made its combat debut in Britain in May 1942. After the war, Henry became Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Civil Aviation. Self was appointed KCB (1939) and KBE (1947).

Colonel Sir Edmund Vivian Gabriel

Title page lower left

(1875-1950) Edmund Vivian Gabriel was a descendant of Italian nobility, British civil servant, courtier, and art collector who played noteworthy roles in both the First and Second World Wars. Gabriel served in the Indian Civil and Political Services before being assigned to the Imperial General Staff in London during the First World War, where he was closely associated with Kitchener. He subsequently joined the British Military Mission with the Italian Royal Army, as the head of the intelligence section, and later served as liaison officer to the naval forces in the Aegean. In 1917 he was deployed to Cairo and assigned to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. On 11 December he entered Jerusalem with General Edmund Allenby and was appointed financial advisor and assistant administrator of Palestine but in 1919 was allegedly asked to resign for pro-Arab sympathies. After the war he moved to Britain and maintained his services with the Territorial Army, reaching the rank of colonel. In 1925 he was appointed to King George V’s household as a Gentleman Usher in Ordinary, a title he maintained until his death. During the Second World War, Gabriel was a member of the British Air Commission to the United States of America. Gabriel’s British honors include CSI, CMG, CVO, CBE, and VD. Gabriel was knighted by King George VI in 1937. He was appointed by King Victor Emmanuel III Officer, Order of the Crown of Italy, and Officer, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. He also was a Knight of Justice of the Venerable Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

One thought on “An Extraordinary Copy of Churchill’s First War Speeches Volume”