“Paint like you write or speak. You can do it – every stroke of the brush must be a statement felt & seen…”

- Paul Maze, letter to Winston Churchill, 12 November 1936

As a wordsmith, Churchill was famous for weaving seemingly disparate threads of history and experience, sentiment and perspective to create a cogent and compelling vision. So perhaps it should not be surprising that Churchill was an accomplished and devoted amateur painter; for Churchill, compellingly sharing his perspective was literal as well as figurative, and recreation as well as vocation.

Churchill first took up painting during the First World War. May 1915 saw Churchill scapegoated for failure in the Dardanelles and slaughter at Gallipoli and forced from his Cabinet position at the Admiralty. By November 1915 Churchill was serving at the Front, leading a battalion in the trenches. But during the summer of 1915, as he battled depression, he rented Hoe Farm in Surrey, which he frequented with his wife and three children. One day in June, Churchill noticed his brother’s wife, Gwendeline, sketching in watercolors. Churchill borrowed her brush and swiftly found solace in painting, which would be a passion and source of release and renewal for the remaining half century of his long life.

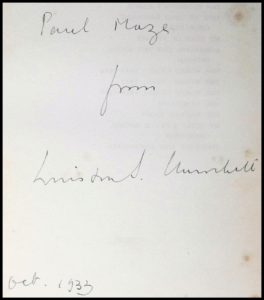

This passion would bind Churchill to French-born painter Paul Maze, Churchill’s close friend, “companion of the brush” and artistic mentor, known as the “last of the Impressionists”. This blog post is prompted by our recent acquisition of a first edition set of Churchill’s Marlborough, inscribed by Churchill to Maze (discussed at the end of this post).

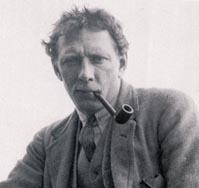

Paul Lucien Maze (1887-1979) was regarded as one of the great artists of his generation and “learned the rudiments of painting from family friends that included Renoir, Monet, Dufy and Pissarro.” His work is held in the collections of many major galleries including The Tate Gallery, the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum.

Paul Lucien Maze (1887-1979) was regarded as one of the great artists of his generation and “learned the rudiments of painting from family friends that included Renoir, Monet, Dufy and Pissarro.” His work is held in the collections of many major galleries including The Tate Gallery, the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum.

Though born in La Havre, Maze was sent to school in Southampton, “where he began a lifelong love affair with all things English.” During the First World War Maze served as an interpreter and engaged in dangerous reconnaissance “as a non-commissioned liaison officer with the British Expeditionary force, using his sketching skills with great bravery to document landscape details in advance of action.” (Coombs, Sir Winston Churchill’s Life Through His Paintings, p.146) He was wounded several times and highly decorated (awarded the DCM, MM and Bar, Legion d’Honneur, and Croix de Guerre). Maze met Churchill on the Western Front in 1916. Churchill had only recently discovered painting, the passion which Maze would encourage and guide as both friend and mentor for the rest of Churchill’s life. Along with Charles Montag, Maze became one of Churchill’s two most important “companions of the brush.”

Maze was naturalized as a British subject in 1920 after marrying the widow of a wartime friend and “took to painting the London scene with great enthusiasm, relishing, like so many French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, the fogs and dingy back streets as much as the pageantry and grandeur of the City’s setting.”

Maze was naturalized as a British subject in 1920 after marrying the widow of a wartime friend and “took to painting the London scene with great enthusiasm, relishing, like so many French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, the fogs and dingy back streets as much as the pageantry and grandeur of the City’s setting.”

Churchill’s official Biographer, Martin Gilbert, called Maze “One of Churchill’s closest French friends.” (Gilbert, VI, p.856) This friendship transcended painting, as is evident from shared moments, perspective, and correspondence between them during Churchill’s 1930s “wilderness years”.

Winston Churchill’s monumental biography of his great ancestor, John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, took 10 years of research and writing and is Churchill’s most substantial published work of the 1930s. This decade saw Churchill pass into his sixties with his own future as uncertain as that of his nation. Churchill may have wondered more than once if the life history he was writing about a great ancestor might ultimately eclipse his own.

Maze, too, was writing about the past. In 1934, the year after Churchill inscribed a copy of his first volume of Marlborough to Maze, Churchill contributed a Foreword to Maze’s First World War memoirs, A Frenchman in Khaki. Churchill wrote: “we have the battle-scenes of Armageddon recorded by one who not only loved the fighting troops and shared their perils, but perceived the beauties of light and shade, of form and colour, of which even the horrors of war cannot rob the progress of the sun.”

Richard Langworth has written “To understand the Churchill of the Second World War, the majestic blending of his commanding English with historical precedent, one has to read Marlborough.”

Maze knew and regarded this Churchill – the statesman and wordsmith – just as well as Churchill the painter.

In 1936, while Churchill was still fully engaged in writing Marlborough, he was also publishing articles on the growing Nazi threat. (“Marlborough alone is a crusher – then there are always articles to boil the pot!” 1/7/1937 letter to Clementine) Maze, who shared his friend’s concerns, wrote to Churchill on 13 March 1936 “How right you have been, as events alas now prove. The public is slowly beginning to see it… Do write to the papers all you can… Keep well – England needs you now more than ever…”

In 12 November 1936, Maze attended the House of Commons to watch Churchill speak and wrote to him afterwards: “I was thrilled by every word you said in the House yesterday – as I went down, the usher downstairs said to me ‘you chose a good day to come, he is always fine – none left like him – he always does one good’. I nearly embraced him – I feel so much what he said! I have sent you some brushes… Paint like you write or speak. You can do it – every stroke of the brush must be a statement felt & seen…”

On the eve of war in 1939, Churchill wrote a Foreword to the catalogue of his friend’s first New York exhibition: “With the fewest of strokes, he can create an impression at once true and beautiful. Here is no toiling seeker after preconceived effects, but a vivid and powerful interpreter to us of the forces and harmony of Nature.”

Later that year, on 20 August 1939, Churchill was painting alongside Maze (at Chateau de Saint-Georges-Motel) when he “suddenly turned” to his friend and said: “This is the last picture we shall paint in peace for a very long time.”

“What amazed me was his concentration over his painting. No one but he could have understood more what the possibility of war meant, and how ill prepared we were. As he worked, he would now and then make statements as to the relative strengths of the German Army or the French Army. ‘They are strong, I tell you, they are strong,’ he would say. Then his jaw would clench his large cigar, and I felt the determination of his will. ‘Ah’ he would say, ‘with it all, we shall have him.’”

Maze recorded that Churchill was depressed as he left: “I had written a letter to him ‘only to read when he was over the Channel’: ‘Don’t worry Winston you know that you will be Prime Minister and lead us to victory…’” (Gilbert, V, p.1103)

On 1 September Nazi Germany invaded Poland and on 3 September Churchill returned to the Admiralty and to war. In May 1940 Churchill became wartime Prime Minister. The next month, Maze “managed to escape through Bordeaux… bringing with him a convoy of orphans.” Maze would serve in the Home Guard in Hampshire before serving as an RAF staff officer. (Gilbert, VI, p.857)

As Churchill’s wilderness years and his friendship with Paul Maze remind us, painting was doubtless a vital stillness in the great and turbulent sweep of Churchill’s otherwise tremendously public life. When he finally published a book on the subject in 1948, Churchill wrote of his and Maze’s shared passion: “Painting is a friend who makes no undue demands, excites to no exhausting pursuits, keeps faithful pace even with feeble steps, and holds her canvas as a screen between us and the envious eyes of Time or the surly advance of Decrepitude.” (Painting as a Pastime).

Post-war, Maze’s friendship with Churchill continued, as did the twining of their respective paths. Churchill served as Queen Elizabeth II’s first Prime Minister, Maze as the Official Painter of her Coronation. Maze was a frequent Chartwell guest, he and Churchill painting together into Churchill’s final years, both in England and in Maze’s native France.

The friendship was posthumously sealed by family alliance when, in 1979, Paul Maze’s grand-daughter, Jeanne Maze, married Winston Churchill’s first cousin once removed, Robert W.C. Spencer-Churchill.

Two months after Volume I was published, on 12 December 1933, T.E. Lawrence wrote to Churchill: “I finished it only yesterday. I wish I had not… Marlborough has the big scene-painting, the informed pictures of men, the sober comment on political method, the humour, irony and understanding of your normal writing: but beyond that it shows more discipline and strength: and great dignity. It is history, solemn and decorative.” Given the role of painting in settling and steadying Churchill during the turbulent 1930s, it is fascinatingly apt and trenchant that a fellow wordsmith like Lawrence would use the “scene-painting” metaphor.

Two months after Volume I was published, on 12 December 1933, T.E. Lawrence wrote to Churchill: “I finished it only yesterday. I wish I had not… Marlborough has the big scene-painting, the informed pictures of men, the sober comment on political method, the humour, irony and understanding of your normal writing: but beyond that it shows more discipline and strength: and great dignity. It is history, solemn and decorative.” Given the role of painting in settling and steadying Churchill during the turbulent 1930s, it is fascinatingly apt and trenchant that a fellow wordsmith like Lawrence would use the “scene-painting” metaphor.

We are pleased to have just listed a full, four-volume set of British first edition, first printings of Churchill’s Marlborough: His Life and Times inscribed in the first volume in the month of publication to Paul Maze. The four-line, inked inscription on the Volume I half-title reads: “Paul Maze | from | Winston S. Churchill | Oct. 1933”. The set is magnificently bound in full orange morocco (evocative of the Publisher’s original signed and limited issue of the first edition), featuring gilt-bordered, raised spine bands, brown morocco title and author labels, gilt front cover frame rules, beveled edge boards, head and foot bands, hand-marbled endpapers, and freshly gilt top edges, and tissue guard bound in preceding the inscription. The set is housed in a stout brown cloth slipcase with brown satin ribbon pull. A full description of the set may be found HERE.

2 thoughts on “Churchill’s friendship with painter Paul Maze”