Recently, I went to a record store with my teenage daughter, where she showed shiny-eyed reverence for old vinyl records – objects that I would have been unable to unload at a garage sale just a few decades ago. I pointed out that she has a subscription to multiple music platforms, each with enormous, on-demand song catalogues that stream with high fidelity through the device of her choice. I pointed out the aesthetic and practical inefficiencies of spinning a frisbee under a needle as a means to consume music, not to mention the silliness of filling shelves with heavy, fragile vinyl discs. Then, I remembered how many bookshelves we have in our house. And, yes, I bought her some vinyl records. Let’s acknowledge that there is much about book collecting that makes no sense.

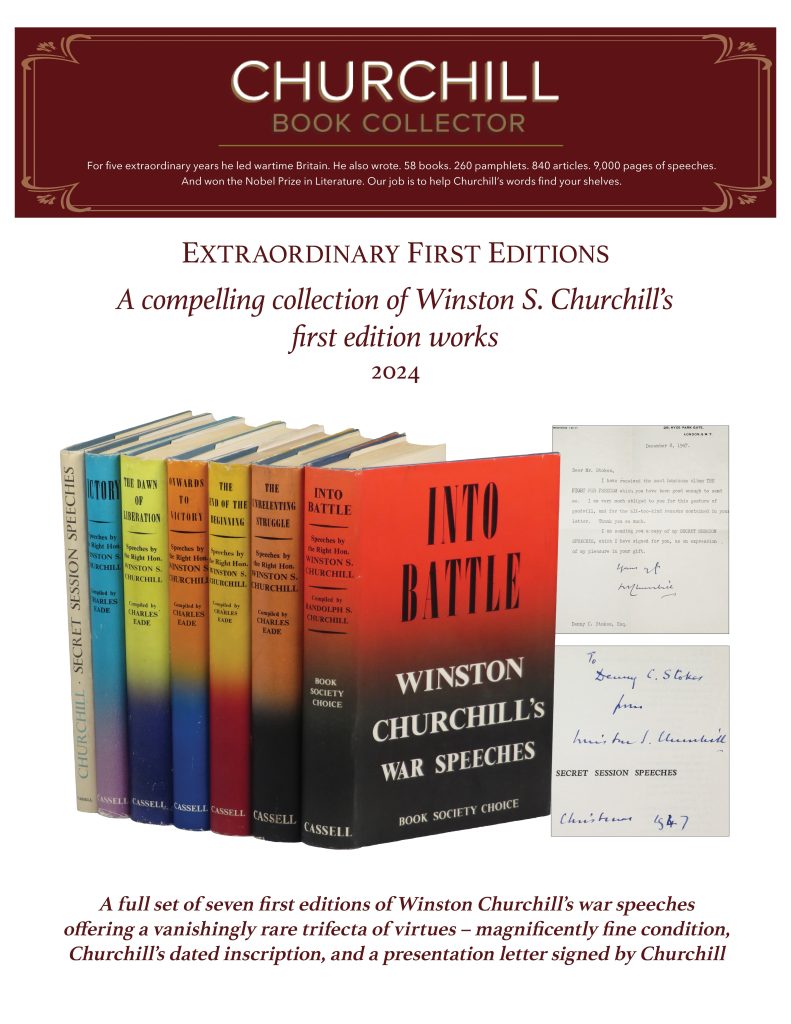

While I’m at it, I’ll also acknowledge that, at the end of the year I tend to get a bit reflective. Hence this post, which revisits and connects a number of perspectives I’ve shared over the years and also shared in our new 2024 catalogue. (Click HERE or on the adjacent image to view the catalogue.)

But I was talking about book collecting and how it makes no sense. So back to it.

Author Nicholas Basbanes wrote a lovely book about the afflicted, aptly titled A Gentle Madness. That title derived from an affectionate description of Isaiah Thomas, the Revolutionary War-era printer, publisher, and author who founded (and contributed his entire, considerable personal library to) the American Antiquarian Society – a still-extant repository for printed records of the United States. Isaiah Thomas was eulogized by his grandson as “touched early by the gentlest of infirmities, bibliomania.”

What was “mania” then is certainly no less now, in our age of almost instantaneously available and nearly infinitely portable information. Sorry Alexandria – one can now carry a literal library on a phone. So why fill shelves with books?

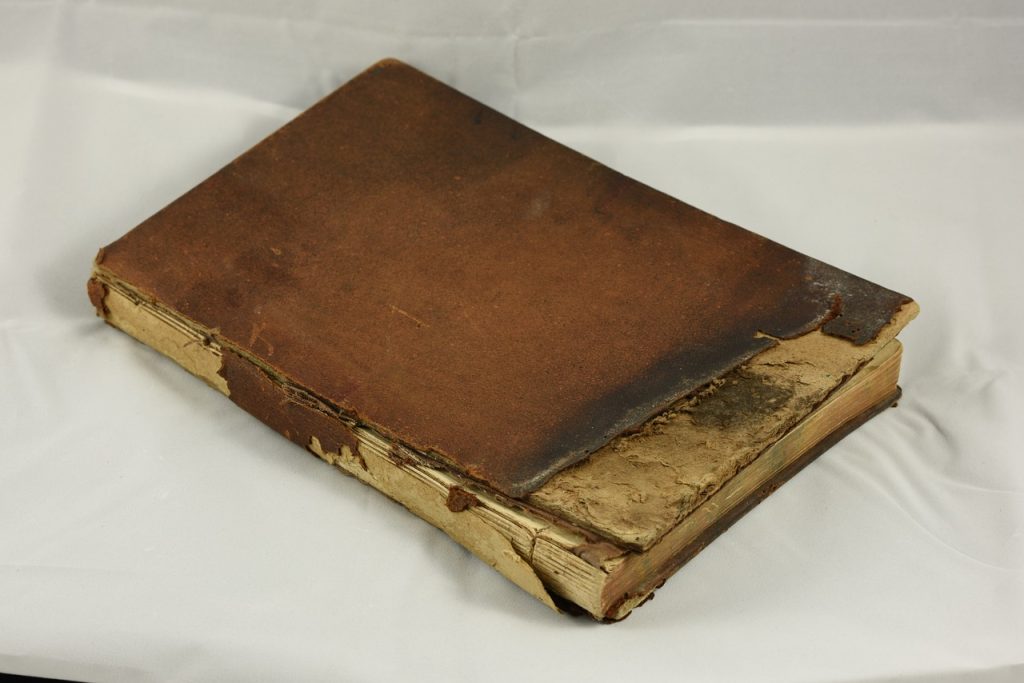

Books are a tenuous combination of perishable materials and discordant chemistry – various types of ink and paper, glue and string and cloth, materials that may be animal, vegetable, synthetic, or all three. The constituent elements of books court entropy and conspire to decohere almost from the moment they are bound together. For the vast majority of books, their purpose is fulfilled in being read and wrecked.

But a very few live a different life. Collectible books transmogrify, becoming something precious, a lingering signal amid the static, objects with a greater purpose than their consumption. And, often, the longer they endure, the better they are regarded.

Here’s something even less sensible. One may pay lots of money for rare or collectible books. But one shouldn’t own them.

That’s right. This bookseller is telling you that you shouldn’t own what you buy.

OK – a clarification so we don’t hear from an attorney… We encourage you not to regard your collectible books as if you own them. We respectfully suggest that your job as a discerning collector is to make sure your collection outlives you and your custody thereof. Relish, of course. Covet, obsess, and even, if you must, brag a little. But foremost, serve as a diligent and conscientious custodian. Take care to preserve what is in your custody. And make sensible provisions to ensure that your charges find a successor custodian with commitment and sensibility equal to your own. Your job is to ensure that what comes into your possession eventually passes from your hands to the next with as much defiance of age and injury as possible.

Why? This is a reasonable question to ask given the assertions above.

Many answers occur. Just to keep things interesting, here’s an answer from a book about… falconry:

“I once asked my friends if they ever held things that gave them a spooky sense of history. Ancient pots with 3,000 year old thumbprints in the clay said one. Antique keys, another. Clay pipes. Dancing shoes from World War II. Roman coins I found in a field. Old bus tickets in second hand books. Everyone agreed that what these small things did was strangely intimate. They gave them the sense as they picked them up and turned them in their fingers of another person, an unknown person a long time ago, who had held that object in their hands. “You don’t know anything about them, but you feel the other person’s there” one friend told me. “It’s like all the years between you and them disappear. Like you become them somehow.” History collapses…”

(from H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald)

Nested within a greater dialogue of what it means to heed and hold a hawk is this rather lovely explanation of why one might wish to have and hold a book. Ms. Macdonald’s passage is an explanation of what a mere thing can convey. In certain books there is a sense of connection embodied in the physical object that exists simultaneous with, yet apart from, the words therein. For some of us, a book can be a small miracle of ephemeral, sentient alignment that we are compelled to conserve. Stewardship of these items is not mere collecting, but an act of safeguarding fragments of our collective, evolving humanity.

Yes, there is a market for rare books. And that market is just as ancient, enduring, and capriciously evolving as the learnings, loves, and lusts that drive us to possess books. But there is also something beyond mere collecting and commerce.

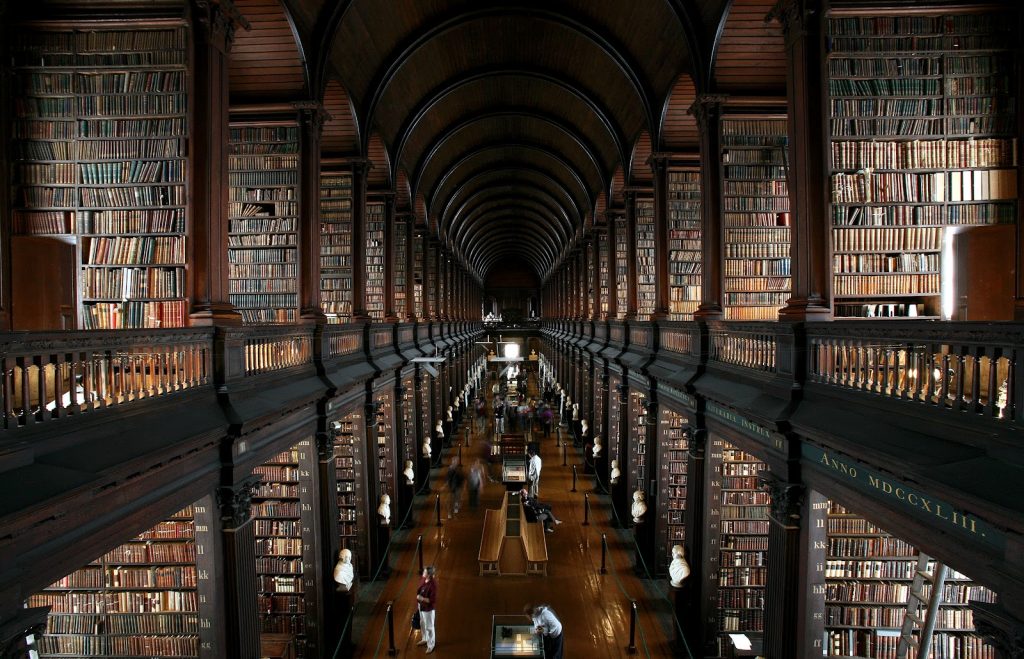

Among and between the pages and stacks and libraries and those who tend them, there is a conversation – a ranging, intermittent, and only vaguely coherent, but nonetheless constant conversation about the conceptions and expressions of who we are and who we hope to be as a species. As the books and ideas therein age and stratify, so too does the conversation. It becomes a susurration, a sort of quiet cultural undercurrent, consistently masked by the prevailing daily tides and wind and weather. But that doesn’t mean the conversational current is either irrelevant or unnecessary. Want of it, one feels, would still the great ocean of our experience, losing it by failing to gently stir its depths while the majority of our energy is always focused on disturbing the surface.

May you be afflicted with “the gentlest of infirmities” and an abundance of shelves.

5 thoughts on “Thoughts on “the gentlest of infirmities””